White Box-Yellow Box-Blakely's Red Gum Woodland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cheetah Conservation Fund Farmlands Wild and Native Species

Cheetah Conservation Fund Farmlands Wild and Native Species List Woody Vegetation Silver terminalia Terminalia sericea Table SEQ Table \* ARABIC 3: List of com- Blue green sour plum Ximenia Americana mon trees, scrub, and understory vegeta- Buffalo thorn Ziziphus mucronata tion found on CCF farms (2005). Warm-cure Pseudogaltonia clavata albizia Albizia anthelmintica Mundulea sericea Shepherds tree Boscia albitrunca Tumble weed Acrotome inflate Brandy bush Grevia flava Pig weed Amaranthus sp. Flame acacia Senegalia ataxacantha Wild asparagus Asparagus sp. Camel thorn Vachellia erioloba Tsama/ melon Citrullus lanatus Blue thorn Senegalia erubescens Wild cucumber Coccinea sessilifolia Blade thorn Senegalia fleckii Corchorus asplenifolius Candle pod acacia Vachellia hebeclada Flame lily Gloriosa superba Mountain thorn Senegalia hereroensis Tribulis terestris Baloon thron Vachellia luederitziae Solanum delagoense Black thorn Senegalia mellifera subsp. Detin- Gemsbok bean Tylosema esculentum ens Blepharis diversispina False umbrella thorn Vachellia reficience (Forb) Cyperus fulgens Umbrella thorn Vachellia tortilis Cyperus fulgens Aloe littoralis Ledebouria spp. Zebra aloe Aloe zebrine Wild sesame Sesamum triphyllum White bauhinia Bauhinia petersiana Elephant’s ear Abutilon angulatum Smelly shepherd’s tree Boscia foetida Trumpet thorn Catophractes alexandri Grasses Kudu bush Combretum apiculatum Table SEQ Table \* ARABIC 4: List of com- Bushwillow Combretum collinum mon grass species found on CCF farms Lead wood Combretum imberbe (2005). Sand commiphora Commiphora angolensis Annual Three-awn Aristida adscensionis Brandy bush Grevia flava Blue Buffalo GrassCenchrus ciliaris Common commiphora Commiphora pyran- Bottle-brush Grass Perotis patens cathioides Broad-leaved Curly Leaf Eragrostis rigidior Lavender bush Croton gratissimus subsp. Broom Love Grass Eragrostis pallens Gratissimus Bur-bristle Grass Setaria verticillata Sickle bush Dichrostachys cinerea subsp. -

Southside Camera Club March 2018 Newsletter

F22: Southside Camera Club newsletter Volume 26 – Issue 2: March 2018 Contents Meetings 7:30 pm: Deakin Soccer Club, 3 Grose Street, Deakin First Tuesday of the month for general meetings; fourth Tuesday for DIG SIG What’s on this month 1 Reports 2 President’s report 2 Lake Eyre and the Flinders Ranges, a photography road trip Recent outings 2 Warren Hicks will do a presentation on a 2016 trip to South Australia Future events and meetings 3 Upcoming excursions 4 Queanbeyan Rodeo: Sat 10 March; 3:00 pm till... 4 ANU Enlighten: Thur 15 March 4 Online resources 4 From Paul Livingston 4 Exhibitions and workshops 4 Atlas of Life in the Coastal Wilderness 4 Introduction Photography Workshop 4 The Club online 4 Web site 4 Facebook 4 flickr 4 Photo sharpness 5 Equipment list 5 Office bearers 5 F22 gallery 6 What’s on this month Date Meeting, excursion, walkabout or group event Speaker/convenor Tues 6 March Meeting: Lake Eyre and the Flinders Ranges, a photography Warren Hicks road trip Sat 10 March Balloon Festival: Arrive before 6:15 am for first balloons Brian Moir filling Sat 10 March Queanbeyan Rodeo. Start time 3:00 pm Ann Gibbs-Jordan Thurs 15 March Enlighten at the ANU (Evening) Dine and stroll along the Helen Dawes new ANU ‘Mind/thinking and spaces’. Tues 27 March DIG SIG Norman Blom Sat 31 March Portrait Interest Group Malcolm Watson Reports visit to Paul’s studio in the village square is well worth it. If you can’t make it to the studio his work is found on his web site. -

Landscape Report Template

MURRAY REGION DESTINATION MANAGEMENT PLAN MURRAY REGIONAL TOURISM www.murrayregionaltourism.com.au AUTHORS Mike Ruzzene Chris Funtera Urban Enterprise Urban Planning, Land Economics, Tourism Planning & Industry Software 389 St Georges Rd, Fitzroy North, VIC 3068 (03) 9482 3888 www.urbanenterprise.com.au © Copyright, Murray Regional Tourism This work is copyright. Apart from any uses permitted under Copyright Act 1963, no part may be reproduced without written permission of Murray Regional Tourism DISCLAIMER Neither Urban Enterprise Pty. Ltd. nor any member or employee of Urban Enterprise Pty. Ltd. takes responsibility in any way whatsoever to any person or organisation (other than that for which this report has been prepared) in respect of the information set out in this report, including any errors or omissions therein. In the course of our preparation of this report, projections have been prepared on the basis of assumptions and methodology which have been described in the report. It is possible that some of the assumptions underlying the projections may change. Nevertheless, the professional judgement of the members and employees of Urban Enterprise Pty. Ltd. have been applied in making these assumptions, such that they constitute an understandable basis for estimates and projections. Beyond this, to the extent that the assumptions do not materialise, the estimates and projections of achievable results may vary. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 5.3. TOURISM PRODUCT STRENGTHS 32 1. INTRODUCTION 10 PART B. DESTINATION MANAGEMENT PLAN FRAMEWORK 34 1.1. PROJECT SCOPE AND OBJECTIVES 10 6. DMP FRAMEWORK 35 1.2. THE REGION 10 6.1. OVERVIEW 35 1.3. INTEGRATION WITH DESTINATION RIVERINA MURRAY 12 7. -

Bushtracks Bush Heritage Magazine | Summer 2019

bushtracks Bush Heritage Magazine | Summer 2019 Outback extremes Darwin’s legacy Platypus patrol Understanding how climate How a conversation beneath Volunteers brave sub-zero change will impact our western gimlet gums led to the creation temperatures to help shed light Queensland reserves. of Charles Darwin Reserve. on the Platypus of the upper Murrumbidgee River. Bush Heritage acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the places in which we live, work and play. We recognise and respect the enduring relationship they have with their lands and waters, and we pay our respects to elders, past and present. CONTRIBUTORS 1 Ethabuka Reserve, Qld, after rains. Photo by Wayne Lawler/EcoPix Chris Grubb Clare Watson Dr Viki Cramer Bron Willis Amelia Caddy 2 DESIGN Outback extremes Viola Design COVER IMAGE Ethabuka Reserve in far western Queensland. Photo by Lachie Millard / 8 The Courier Mail Platypus control This publication uses 100% post- 10 consumer waste recycled fibre, made Darwin’s legacy with a carbon neutral manufacturing process, using vegetable-based inks. BUSH HERITAGE AUSTRALIA T 1300 628 873 E [email protected] 13 W www.bushheritage.org.au Parting shot Follow Bush Heritage on: few years ago, I embarked on a scientific they describe this work reminds me that we are all expedition through Bush Heritage’s Ethabuka connected by our shared passion for the bush and our Aa Reserve, which is located on the edge of the dedication to seeing healthy country, protected forever. Simpson Desert, in far western Queensland. We were prepared for dry conditions and had packed ten Over the past 27 years, this same passion and days’ worth of water, but as it happened, our visit to dedication has seen Bush Heritage grow from strength- Ethabuka coincided with a rare downpour – the kind to-strength through two evolving eras of leadership of rain that transforms desert landscapes. -

Birds of Gunung Tambora, Sumbawa, Indonesia: Effects of Altitude, the 1815 Cataclysmic Volcanic Eruption and Trade

FORKTAIL 18 (2002): 49–61 Birds of Gunung Tambora, Sumbawa, Indonesia: effects of altitude, the 1815 cataclysmic volcanic eruption and trade COLIN R. TRAINOR In June-July 2000, a 10-day avifaunal survey on Gunung Tambora (2,850 m, site of the greatest volcanic eruption in recorded history), revealed an extraordinary mountain with a rather ordinary Sumbawan avifauna: low in total species number, with all species except two oriental montane specialists (Sunda Bush Warbler Cettia vulcania and Lesser Shortwing Brachypteryx leucophrys) occurring widely elsewhere on Sumbawa. Only 11 of 19 restricted-range bird species known for Sumbawa were recorded, with several exceptional absences speculated to result from the eruption. These included: Flores Green Pigeon Treron floris, Russet-capped Tesia Tesia everetti, Bare-throated Whistler Pachycephala nudigula, Flame-breasted Sunbird Nectarinia solaris, Yellow-browed White- eye Lophozosterops superciliaris and Scaly-crowned Honeyeater Lichmera lombokia. All 11 resticted- range species occurred at 1,200-1,600 m, and ten were found above 1,600 m, highlighting the conservation significance of hill and montane habitat. Populations of the Yellow-crested Cockatoo Cacatua sulphurea, Hill Myna Gracula religiosa, Chestnut-backed Thrush Zoothera dohertyi and Chestnut-capped Thrush Zoothera interpres have been greatly reduced by bird trade and hunting in the Tambora Important Bird Area, as has occurred through much of Nusa Tenggara. ‘in its fury, the eruption spared, of the inhabitants, not a although in other places some vegetation had re- single person, of the fauna, not a worm, of the flora, not a established (Vetter 1820 quoted in de Jong Boers 1995). blade of grass’ Francis (1831) in de Jong Boers (1995), Nine years after the eruption the former kingdoms of referring to the 1815 Tambora eruption. -

CBD Sixth National Report

Australia’s Sixth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity 2014 2018 ‒ 24 March 2020 © Commonwealth of Australia 2020 Ownership of intellectual property rights Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights) in this publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia (referred to as the Commonwealth). Creative Commons licence All material in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence except content supplied by third parties, logos and the Commonwealth Coat of Arms. Inquiries about the licence and any use of this document should be emailed to [email protected]. Cataloguing data This report should be attributed as: Australia’s Sixth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity 2014‒2018, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2020 CC BY 4.0. ISBN 978-1-76003-255-5 This publication is available at http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/international/un-convention-biological-diversity. Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment GPO Box 858 Canberra ACT 2601 Telephone 1800 900 090 Web awe.gov.au The Australian Government acting through the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment has exercised due care and skill in preparing and compiling the information and data in this publication. Notwithstanding, the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, its employees and advisers disclaim all liability, including liability for negligence and for any loss, damage, injury, expense or cost incurred by any person as a result of accessing, using or relying on any of the information or data in this publication to the maximum extent permitted by law. -

Annual Report 2001-2002 (PDF

2001 2002 Annual report NSW national Parks & Wildlife service Published by NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service PO Box 1967, Hurstville 2220 Copyright © National Parks and Wildlife Service 2002 ISSN 0158-0965 Coordinator: Christine Sultana Editor: Catherine Munro Design and layout: Harley & Jones design Printed by: Agency Printing Front cover photos (from top left): Sturt National Park (G Robertson/NPWS); Bouddi National Park (J Winter/NPWS); Banksias, Gibraltar Range National Park Copies of this report are available from the National Parks Centre, (P Green/NPWS); Launch of Backyard Buddies program (NPWS); Pacific black duck 102 George St, The Rocks, Sydney, phone 1300 361 967; or (P Green); Beyers Cottage, Hill End Historic Site (G Ashley/NPWS). NPWS Mail Order, PO Box 1967, Hurstville 2220, phone: 9585 6533. Back cover photos (from left): Python tree, Gossia bidwillii (P Green); Repatriation of Aboriginal remains, La Perouse (C Bento/Australian Museum); This report can also be downloaded from the NPWS website: Rainforest, Nightcap National Park (P Green/NPWS); Northern banjo frog (J Little). www.npws.nsw.gov.au Inside front cover: Sturt National Park (G Robertson/NPWS). Annual report 2001-2002 NPWS mission G Robertson/NPWS NSW national Parks & Wildlife service 2 Contents Director-General’s foreword 6 3Conservation management 43 Working with Aboriginal communities 44 Overview Joint management of national parks 44 Mission statement 8 Aboriginal heritage 46 Role and functions 8 Outside the reserve system 47 Customers, partners and stakeholders -

Western Track Diagrams Version: 3.3 Western Division - Track Diagrams

Western Track Diagrams Manager, Operator and Maintainer of the New South Wales Country Rail Network Disclaimer. This document may not contain the latest infrastructure information. If there is any doubt please refer to the relevant CLNA and current Safe Notices. John Holland Rail Pty Ltd makes no warranties, express or implied, that compliance with the contents of this document shall be sufficient to ensure safe systems of work or operation. It is the document user’s sole responsibility to ensure that the copy of the document it is viewing is the current version of the document as in use by JHR. JHR accepts no liability whatsoever in relation to the use of this document by any party, and JHR excludes any liability which arises in any manner by the use of this document. western File: West Diagram Cover V3.4.cdr Western Division - Track Diagrams Document control Revision Date of Issue Summary of change 3.0 22/2/17 Diagrams generally updated 3.1 18/6/18 Diagrams generally updated 3.3 18/01/2019 Diagrams generally updated 3.5 22/08/2019 Georges Plains and Rydal Loops added The following location have been modified: • Hermidale loop added 3.6 9/04/2020 • Nyngan loop extended • Wongabon loop removed • Stop block added after Warren South Summary of changes from previous version Section Summary of change 9 Wongabon loop removed 17 Nyngan loop extended 18 Hermidale loop added 21 Stop block added after Warren South © JHR UNCONTROLLED WHEN PRINTED Page 1 of 34 Western Track Diagrams Version: 3.3 Western Division - Track Diagrams © JHR UNCONTROLLED -

Macquarie River Bird Trail

Bird Watching Trail Guide Acknowledgements RiverSmart Australia Limited would like to thank the following for their assistance in making this trail and publication a reality. Tim and Janis Hosking, and the other members of the Dubbo Field Naturalists and Conservation Society, who assisted with technical information about the various sites, the bird list and with some of the photos. Thanks also to Jim Dutton for providing bird list details for the Burrendong Arboretum. Photographers. Photographs were kindly provided by Brian O’Leary, Neil Zoglauer, Julian Robinson, Lisa Minner, Debbie Love, Tim Hosking, Dione Carter, Dan Giselsson, Tim Ralph and Bill Phillips. This project received financial support from the Australian Bird Environment Foundation of Sacred kingfisher photo: Dan Giselsson BirdLife Australia. Thanks to Warren Shire Council, Sarah Derrett and Ashley Wielinga in particular, for their assistance in relation to the Tiger Bay site. Thanks also to Philippa Lawrence, Sprout Design and Mapping Services Australia. THE MACQuarIE RIVER TraILS First published 2014 The Macquarie valley, in the heart of NSW is one of the The preparation of this guide was coordinated by the not-for-profit organisation Riversmart State’s — and indeed Australia’s — best kept secrets, until now. Australia Ltd. Please consider making a tax deductible donation to our blue bucket fund so we can keep doing our work in the interests of healthy and sustainable rivers. Macquarie River Trails (www.rivertrails.com.au), launched in late 2011, is designed to let you explore the many attractions www.riversmart.org.au and wonders of this rich farming region, one that is blessed See outside back cover for more about our work with a vibrant river, the iconic Maquarie Marshes, friendly people and a laid back lifestyle. -

Semi-Evergreen Vine Thickets of the Brigalow Belt (North and South) And

145° 150° 155° Semi-evergreen vine thickets of the Brigalow Belt (North and South) and ° ° Nandewar Bioregions 0 Charters Towers 0 2 " 2 - - This is an indicative map only and it is not intended for fine scale assessment. Mackay " Legend Winton " Ecological community likely to occur Brigalow Belt (North and South) and Nandewar Bioregions Emerald " Major Roads Gladstone " Note: The areas of Semi-evergreen vine thickets of the Blackall Brigalow Belt (North and South) and Nandewar Bioregions in " Queensland shown on this map all contain the ecological community but may have varying proportions of other communities Bundaberg mixed within the Semi-evergreen vine thickets. ° " ° 5 5 2 2 - - Source: Semi-evergreen vine thickets of the Brigalow Belt (North and South) and Nandewar Bioregions. The distribution in Queensland consists of Regional Ecosystems Nos 11.3.11, 11.4.1, 11.5.15, 11.8.13, 11.9.4, 11.11.18, 11.2.3, 11.8.3, 11.8.6, and 11.9.8 as defined by Sattler, P. and Williams, R. (eds) (1999). The Conservation of Queensland's Bioregional Ecosystems, Qld EPA Roma and mapped by Queensland Herbarium (Remnant Vegetation 2005 " v5). The distribution in NSW is from the Department of the Environment and Heritage's Native Vegetation Information System (NVIS), 2006. The following attributes were mapped from the Dalby 'Source_Code' field; e3 - Semi-evergreen Vine Thicket. Addtional areas " were derived according to Benson, J.S., Dick, R. and Zubovic, A. Brisbane " (1996). Semi-evergreen vine thicket vegetation at Derra Derra Ridge, Bingara, New South Wales. Cunninghamia 4(3): 497-510; and the Nomination. -

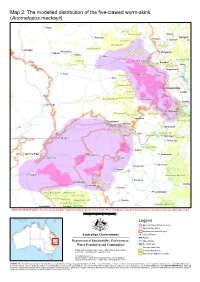

The Modelled Distribution of the Five-Clawed Worm-Skink (Anomalopus Mackayii)

Map 2: The modelled distribution of the five-clawed worm-skink (Anomalopus mackayii) Injune Koko SF Allies Creek SF Kilkivan Wandoan Proston Gympie Jarrah SF Goomeri Barakula SF Wondai SF Gurulmundi SF Mitchell Wallumbilla Roma Diamondy SF Kingaroy Yuleba Nudley SF Miles Chinchilla Conondale FR Yuleba SF Jandowae Blackbutt Bunya Mountains NP Kilcoy Benarkin SF Toogoolawah Surat Braemar SF Dalby Esk Tara Kumbarilla SF Toowoomba Dunmore SF Laidley Western Creek SF Boondandilla SF Millmerran Boonah St George Main Range NP Warwick Whetstone SF State Forest Durikai SF Border Ranges NP Inglewood Goondiwindi Toonumbar NP Boggabilla Yelarbon Stanthorpe Dthinna Dthinnawan CCAZ Texas Girraween NP Sundown NP Wallangarra Mungindi Girard SF Tenterfield Torrington SCA Ashford Lightning Ridge Moree Deepwater Collarenebri Warialda Glen Innes Inverell Bingara Walgett Guy Fawkes River NP Bundarra Wee Waa Mt Kaputar NP Dorrigo Narrabri Barraba Pilliga West CCAZ Pilliga CCAZ Armidale Pilliga East SF Pilliga West SF Euligal SF Pilliga East CCAZ Manilla Timallallie CCAZ Oxley Wild Rivers NP Coonamble Baradine Pilliga NR INDICATIVE MAP ONLY: For the latest departmental information, please refer to the Protected Matters Search Tool at www.environment.gov.au/epbc/index.html km 0 20 40 60 80 100 Legend Species Known/Likely to Occur Species May Occur Brigalow Belt IBRA Region ! Cities & Towns Roads Major Rivers Perennial Lake ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! !! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! !! ! !! ! Non-perennial Lake Produced by: Environmental Resources Information Network (ERIN) Conservation Areas COPYRIGHT Commonwealth of Australia, 2011 Forestry & Indigenous Lands Contextual data sources: DEWHA (2006), Collaborative Australian Protected Areas Database Geoscience Australia (2006), Geodata Topo 250K Topographic Data CAVEAT: The information presented in this map has been provided by a range of groups and agencies. -

The Old Hume Highway History Begins with a Road

The Old Hume Highway History begins with a road Routes, towns and turnoffs on the Old Hume Highway RMS8104_HumeHighwayGuide_SecondEdition_2018_v3.indd 1 26/6/18 8:24 am Foreword It is part of the modern dynamic that, with They were propelled not by engineers and staggering frequency, that which was forged by bulldozers, but by a combination of the the pioneers long ago, now bears little or no needs of different communities, and the paths resemblance to what it has evolved into ... of least resistance. A case in point is the rough route established Some of these towns, like Liverpool, were by Hamilton Hume and Captain William Hovell, established in the very early colonial period, the first white explorers to travel overland from part of the initial push by the white settlers Sydney to the Victorian coast in 1824. They could into Aboriginal land. In 1830, Surveyor-General not even have conceived how that route would Major Thomas Mitchell set the line of the Great look today. Likewise for the NSW and Victorian Southern Road which was intended to tie the governments which in 1928 named a straggling rapidly expanding pastoral frontier back to collection of roads and tracks, rather optimistically, central authority. Towns along the way had mixed the “Hume Highway”. And even people living fortunes – Goulburn flourished, Berrima did in towns along the way where trucks thundered well until the railway came, and who has ever through, up until just a couple of decades ago, heard of Murrimba? Mitchell’s road was built by could only dream that the Hume could be convicts, and remains of their presence are most something entirely different.