Lasker's Manual of Chess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evans Gambit and Giuoco Piano

Chapter Three Evans Gambit and Giuoco Piano d Introduction d Evans Gambit d Giuoco Piano Evans Gambit and Giuoco Piano Introduction These two openings arise after Black develops his bishop to the active-looking c5- square. In both cases White challenges the bishop and aims to gain time to con- struct his centre and prepare an attack. In the Evans Gambit (Games 17-19) White does this directly with 4 b4, already bar- ing his teeth and announcing to his opponent that there won’t be a comfortable ride in the opening. In the Giuoco Piano (Games 20-24) White instead plays c2-c3 and d2-d4, creating tension in the central arena before the players have had time to castle. We will examine Black’s main options in the illustrative games that follow. My impression is that if Black is serious about challenging White’s central aspirations, then he has to be willing to enter complications. The other main option, 4 d3, leading to quieter play, was dealt with separately in Chapter One. Evans Gambit 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 (Diagram 1) The Evans used to be considered as a swashbuckling attempt to attack at all costs. Nowadays this view has moderated, but few would argue with the premise that it is still a risky attempt to seize the initiative. Strategy White opens lines while gaining time against the c5-bishop and, as a result, is able to create some early threats with Black’s king still in the centre. Naturally there is a price to pay for all this action: a pawn or two for a start, plus a compromised queenside, so if Black survives the early assault he may obtain the advantage. -

Dvoretsky Lessons 48

The Instructor The Effects of Replaying I have frequently mentioned, in books and articles, an effective training method: replaying specially selected positions – positions which cannot be “resolved” from beginning to end, so there is really no sense in trying. Instead, players must find, in succession, a series of correct decisions independently (or nearly independently) of each other. In the majority of such exercises, play continues for a minimum of ten moves, although sometimes longer. After all, a shorter variant could in fact be calculated from beginning to end, which would then abolish it as a playing exercise. But The there are sometimes exceptions. The brilliant attack from the following game, which remained hidden in the Instructor annotations, and which is now offered for your consideration, has for some reason never become widely known, although its basic ideas were demonstrated Mark Dvoretsky in Mikhail Botvinnik’s annotations from his book 1941 Match-Tournament. But even those who are familiar with Botvinnik’s analysis will be none the worse for it – for they too will see sharp new variations. Botvinnik - Bondarevsky Leningrad/Moscow 1941 So – you have White. Try to find each move in turn, taking Black’s replies from the following text. Or you might play out this fragment against a friend: he will also find it a problem requiring deep insight into the position. 39.Ne2xd4! In combination with White’s next move, this is a rather obvious exchange: in this way, White gets the opportunity to speculate on the pin along the a1-h8 diagonal. In the game, Botvinnik played the much weaker 39.Ng3?, and after 39...Qe6! 40.Re2 Be3, he ought to have been dead lost: White has neither his pawn, nor any sort of compensation for it. -

Recovering and Rendering Vital Blueprint for Counter Education At

Recovering and Rendering Vital clash that erupted between the staid, conservative Board of Trustees and the raucous experimental work and atti- Blueprint for Counter Education tudes put forth by students and faculty (the latter often- times more militant than the former). The full story of the at the California Institute of the Arts Institute during its frst few years requires (and deserves) an entire book,8 but lines from a 1970 letter by Maurice Paul Cronin Stein, founding Dean of the School of Critical Studies, written a few months before the frst students arrived on campus, gives an indication of the conficts and delecta- tions to come: “This is the most hectic place in the world at the moment and promises to become even more so. At heart of the California Institute of Arts’ campus is We seem to be testing some complex soap opera prop- a vast, monolithic concrete building, containing more osition about the durability of a marriage between the than a thousand rooms. Constructed on a sixty-acre site radical right and left liberals. My only way of adjusting to thirty-fve miles north of Los Angeles, it is centered in the situation is to shut my eyes, do my job, and hope for what at the end of the 1960s was the remote outpost the best.”9 of sun-scorched Valencia (a town “dreamed up by real estate developers to receive the urban sprawl which is • • • Los Angeles”),1 far from Hollywood, a town that was—for many students at the Institute—the belly of the beast. -

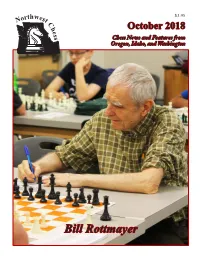

Bill Rottmayer on the Front Cover: Northwest Chess Bill Rottmayer, the Oldest Participant in the Spokane Falls October 2018, Volume 72-10 Issue 849 Open

$3.95 orthwes N t C h October 2018 e s s Chess News and Features from Oregon, Idaho, and Washington Bill Rottmayer On the front cover: Northwest Chess Bill Rottmayer, the oldest participant in the Spokane Falls October 2018, Volume 72-10 Issue 849 Open. Bill has participated in most Spokane Chess Club events the last few years. Photo credit: James Stripes. ISSN Publication 0146-6941 Published monthly by the Northwest Chess Board. On the back cover: POSTMASTER: Send address changes to the Office of Record: Northwest Chess c/o Orlov Chess Academy 4174 148th Ave NE, Dustin Herker at the Las Vegas International Festival where Building I, Suite M, Redmond, WA 98052-5164. he won first place U1000. Photo credit: Nancy Keller. Periodicals Postage Paid at Seattle, WA USPS periodicals postage permit number (0422-390) Chesstoons: NWC Staff Chess cartoons drawn by local artist Brian Berger, Editor: Jeffrey Roland, of West Linn, Oregon. [email protected] Games Editor: Ralph Dubisch, [email protected] Publisher: Duane Polich, Submissions [email protected] Submissions of games (PGN format is preferable for games), Business Manager: Eric Holcomb, stories, photos, art, and other original chess-related content [email protected] are encouraged! Multiple submissions are acceptable; please indicate if material is non-exclusive. All submissions are Board Representatives subject to editing or revision. Send via U.S. Mail to: David Yoshinaga, Josh Sinanan, Jeffrey Roland, NWC Editor Jeffrey Roland, Adam Porth, Chouchanik Airapetian, 1514 S. Longmont Ave. Brian Berger, Duane Polich, Alex Machin, Eric Holcomb. Boise, Idaho 83706-3732 or via e-mail to: Entire contents ©2018 by Northwest Chess. -

Taming Wild Chess Openings

Taming Wild Chess Openings How to deal with the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly over the chess board By International Master John Watson & FIDE Master Eric Schiller New In Chess 2015 1 Contents Explanation of Symbols ���������������������������������������������������������������� 8 Icons ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 9 Introduction �������������������������������������������������������������������������� 10 BAD WHITE OPENINGS ��������������������������������������������������������������� 18 Halloween Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♘c3 ♘f6 4.♘xe5 ♘xe5 5.d4 . 18 Grünfeld Defense: The Gibbon: 1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 g6 3.♘c3 d5 4.g4 . 20 Grob Attack: 1.g4 . 21 English Wing Gambit: 1.c4 c5 2.b4 . 25 French Defense: Orthoschnapp Gambit: 1.e4 e6 2.c4 d5 3.cxd5 exd5 4.♕b3 . 27 Benko Gambit: The Mutkin: 1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 c5 3.d5 b5 4.g4 . 28 Zilbermints - Benoni Gambit: 1.d4 c5 2.b4 . 29 Boden-Kieseritzky Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♗c4 ♘f6 4.♘c3 ♘xe4 5.0-0 . 31 Drunken Hippo Formation: 1.a3 e5 2.b3 d5 3.c3 c5 4.d3 ♘c6 5.e3 ♘e7 6.f3 g6 7.g3 . 33 Kadas Opening: 1.h4 . 35 Cochrane Gambit 1: 5.♗c4 and 5.♘c3 . 37 Cochrane Gambit 2: 5.d4 Main Line: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘f6 3.♘xe5 d6 4.♘xf7 ♔xf7 5.d4 . 40 Nimzowitsch Defense: Wheeler Gambit: 1.e4 ♘c6 2.b4 . 43 BAD BLACK OPENINGS ��������������������������������������������������������������� 44 Khan Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♗c4 d5 . 44 King’s Gambit: Nordwalde Variation: 1.e4 e5 2.f4 ♕f6 . 45 King’s Gambit: Sénéchaud Countergambit: 1.e4 e5 2.f4 ♗c5 3.♘f3 g5 . -

Little Chess Evaluation Compendium by Lyudmil Tsvetkov, Sofia, Bulgaria

Little Chess Evaluation Compendium By Lyudmil Tsvetkov, Sofia, Bulgaria Version from 2012, an update to an original version first released in 2010 The purpose will be to give a fairly precise evaluation for all the most important terms. Some authors might find some interesting ideas. For abbreviations, p will mean pawns, cp – centipawns, if the number is not indicated it will be centipawns, mps - millipawns; b – bishop, n – knight, k- king, q – queen and r –rook. Also b will mean black and w – white. We will assume that the bishop value is 3ps, knight value – 3ps, rook value – 4.5 ps and queen value – 9ps. In brackets I will be giving purely speculative numbers for possible Elo increase if a specific function is implemented (only for the functions that might not be generally implemented). The exposition will be split in 3 parts, reflecting that opening, middlegame and endgame are very different from one another. The essence of chess in two words Chess is a game of capturing. This is the single most important thing worth considering. But in order to be able to capture well, you should consider a variety of other specific rules. The more rules you consider, the better you will be able to capture. If you consider 10 rules, you will be able to capture. If you consider 100 rules, you will be able to capture in a sufficiently good way. If you consider 1000 rules, you will be able to capture in an excellent way. The philosophy of chess Chess is a game of correlation, and not a game of fixed values. -

Ocm-2019-10-01

OCTOBER 2019 Chess News and Chess History for Oklahoma Jim Markley in 2012. In This Issue: • LAST ROUND • Center State “Oklahoma’s Official Chess Quads Bulletin Covering Oklahoma Chess • on a Regular Schedule Since 1982” IM John Donaldson http://ocfchess.org Review Oklahoma Chess • Foundation Plus Register Online for Free News Bites, Game of the Editor: Tom Braunlich Month, Asst. Ed. Rebecca Rutledge st Puzzles, Published the 1 of each month. Top 25 List, Send story submissions and Tournament tournament reports, etc., by the Reports, 15th of the previous month to and more. mailto:[email protected] ©2019 All rights reserved. 12 Dr. Kester Svendsen (the professor at OU from 1940-1959 who was featured last OCM) was inspired by chess to write the story Last Round, which is presented here in full. This brilliancy was not widely known to chess fans in 1947; it was printed only in old Eastern European magazines and in a book of Charousek’s games. It is an example of how well read Svendsen was as a chess player for him to even be aware of it. In the original story, Svendsen describes the moves of the game using only colorful explanatory words of narrative. Chess World magazine added three diagrams to help the reader. by Dr. Kester Svendsen The Old Master looked down at the board and The director's voice seeped into his reverie. chessmen again, although he had seen their stiff pattern times out of mind. While the "Final round. Rolavsky the Russian champion tournament director was speaking he could leading with seven points. -

Opening Moves - Player Facts

DVD Chess Rules Chess puzzles Classic games Extras - Opening moves - Player facts General Rules The aim in the game of chess is to win by trapping your opponent's king. White always moves first and players take turns moving one game piece at a time. Movement is required every turn. Each type of piece has its own method of movement. A piece may be moved to another position or may capture an opponent's piece. This is done by landing on the appropriate square with the moving piece and removing the defending piece from play. With the exception of the knight, a piece may not move over or through any of the other pieces. When the board is set up it should be positioned so that the letters A-H face both players. When setting up, make sure that the white queen is positioned on a light square and the black queen is situated on a dark square. The two armies should be mirror images of one another. Pawn Movement Each player has eight pawns. They are the least powerful piece on the chess board, but may become equal to the most powerful. Pawns always move straight ahead unless they are capturing another piece. Generally pawns move only one square at a time. The exception is the first time a pawn is moved, it may move forward two squares as long as there are no obstructing pieces. A pawn cannot capture a piece directly in front of him but only one at a forward angle. When a pawn captures another piece the pawn takes that piece’s place on the board, and the captured piece is removed from play If a pawn gets all the way across the board to the opponent’s edge, it is promoted. -

An Introduction to the Danish Gambit Accepted Richard Westbrook, 2006

An Introduction to the Danish Gambit Accepted Richard Westbrook, 2006 The Danish Gambit is a variation of the The popularity of the Danish fell after Center Game and begins with the moves Schlechter's defense was introduced because 1.e4 e5 2.d4 exd4 3.c3. The Danish is closely the resulting positions are not what White related to the Scotch and Goring Gambits, generally desires from a gambit opening. depending on the timing of the development Nevertheless, it is worth learning as a way to of White’s kingside pieces. (It was popular improve your tactical skills and to be aware of with masters of attack including Alekhine, what not to do defensively. Marshall, Blackburne, and Mieses, but when Black's defenses improved it lost favor.) 1.e4 e5 Today it is rarely played at the higher levels. 2.d4 exd4 3.c3 dxc3 White sacrifices one or two pawns for the sake of rapid development and attack. Black Or, 3... Qe7! can accept one or both pawns safely, or 4.Qxd4 Nc6 simply decline the gambit altogether with 1.e4 5.Qe3 Nf6 e5 2.d4 exd4 3.c3, by playing 3...d6!?, or 6.Bd3 Ne5 3...d5, but best is probably the awkward 7.Bc2 d5 =/+. looking 3…Qe7!. Or, 3... d5!? If Black enters the Danish Gambit Accepted 4.Qxd4 Qe7 =. with 3...dxc3, White offers a second pawn with 4.Bc4 which can be safely declined by 4.Bc4 … transposing into the Scotch Gambit. Accepting the pawn allows White's two Alekhine recommended a "half-Danish" bishops to rake the Black kingside after 4.Nxc3 which may transpose into the Scotch 4...cxb2 5.Bxb2. -

Chess Openings

Chess Openings PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Tue, 10 Jun 2014 09:50:30 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Chess opening 1 e4 Openings 25 King's Pawn Game 25 Open Game 29 Semi-Open Game 32 e4 Openings – King's Knight Openings 36 King's Knight Opening 36 Ruy Lopez 38 Ruy Lopez, Exchange Variation 57 Italian Game 60 Hungarian Defense 63 Two Knights Defense 65 Fried Liver Attack 71 Giuoco Piano 73 Evans Gambit 78 Italian Gambit 82 Irish Gambit 83 Jerome Gambit 85 Blackburne Shilling Gambit 88 Scotch Game 90 Ponziani Opening 96 Inverted Hungarian Opening 102 Konstantinopolsky Opening 104 Three Knights Opening 105 Four Knights Game 107 Halloween Gambit 111 Philidor Defence 115 Elephant Gambit 119 Damiano Defence 122 Greco Defence 125 Gunderam Defense 127 Latvian Gambit 129 Rousseau Gambit 133 Petrov's Defence 136 e4 Openings – Sicilian Defence 140 Sicilian Defence 140 Sicilian Defence, Alapin Variation 159 Sicilian Defence, Dragon Variation 163 Sicilian Defence, Accelerated Dragon 169 Sicilian, Dragon, Yugoslav attack, 9.Bc4 172 Sicilian Defence, Najdorf Variation 175 Sicilian Defence, Scheveningen Variation 181 Chekhover Sicilian 185 Wing Gambit 187 Smith-Morra Gambit 189 e4 Openings – Other variations 192 Bishop's Opening 192 Portuguese Opening 198 King's Gambit 200 Fischer Defense 206 Falkbeer Countergambit 208 Rice Gambit 210 Center Game 212 Danish Gambit 214 Lopez Opening 218 Napoleon Opening 219 Parham Attack 221 Vienna Game 224 Frankenstein-Dracula Variation 228 Alapin's Opening 231 French Defence 232 Caro-Kann Defence 245 Pirc Defence 256 Pirc Defence, Austrian Attack 261 Balogh Defense 263 Scandinavian Defense 265 Nimzowitsch Defence 269 Alekhine's Defence 271 Modern Defense 279 Monkey's Bum 282 Owen's Defence 285 St. -

Chess Camp Volume 3: Checkmates with Many Pieces Contents Note for Coaches, Parents, Teachers, and Trainers

Igor Sukhin Chess Camp Volume 3: Checkmates with Many Pieces Contents Note for Coaches, Parents, Teachers, and Trainers ........................................................................ 5 Mate in One in the Opening Approaching the Opening ............................................................................................................... 7 Silly Games ......................................................................................................................................13 Open Games ...................................................................................................................................17 Semi-Open Games ...........................................................................................................................40 Closed Games ................................................................................................................................ 49 Mate in One in the Middlegame Pins .................................................................................................................................................55 Silly Pin Positions ............................................................................................................................57 Double Check .................................................................................................................................58 Discovered Check ...........................................................................................................................60 Attacking -

Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames

Games of No Chance MSRI Publications Volume 29, 1996 Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames LEWIS STILLER Abstract. This article has three chief aims: (1) To show the wide utility of multilinear algebraic formalism for high-performance computing. (2) To describe an application of this formalism in the analysis of chess endgames, and results obtained thereby that would have been impossible to compute using earlier techniques, including a win requiring a record 243 moves. (3) To contribute to the study of the history of chess endgames, by focusing on the work of Friedrich Amelung (in particular his apparently lost analysis of certain six-piece endgames) and that of Theodor Molien, one of the founders of modern group representation theory and the first person to have systematically numerically analyzed a pawnless endgame. 1. Introduction Parallel and vector architectures can achieve high peak bandwidth, but it can be difficult for the programmer to design algorithms that exploit this bandwidth efficiently. Application performance can depend heavily on unique architecture features that complicate the design of portable code [Szymanski et al. 1994; Stone 1993]. The work reported here is part of a project to explore the extent to which the techniques of multilinear algebra can be used to simplify the design of high- performance parallel and vector algorithms [Johnson et al. 1991]. The approach is this: Define a set of fixed, structured matrices that encode architectural primitives • of the machine, in the sense that left-multiplication of a vector by this matrix is efficient on the target architecture. Formulate the application problem as a matrix multiplication.