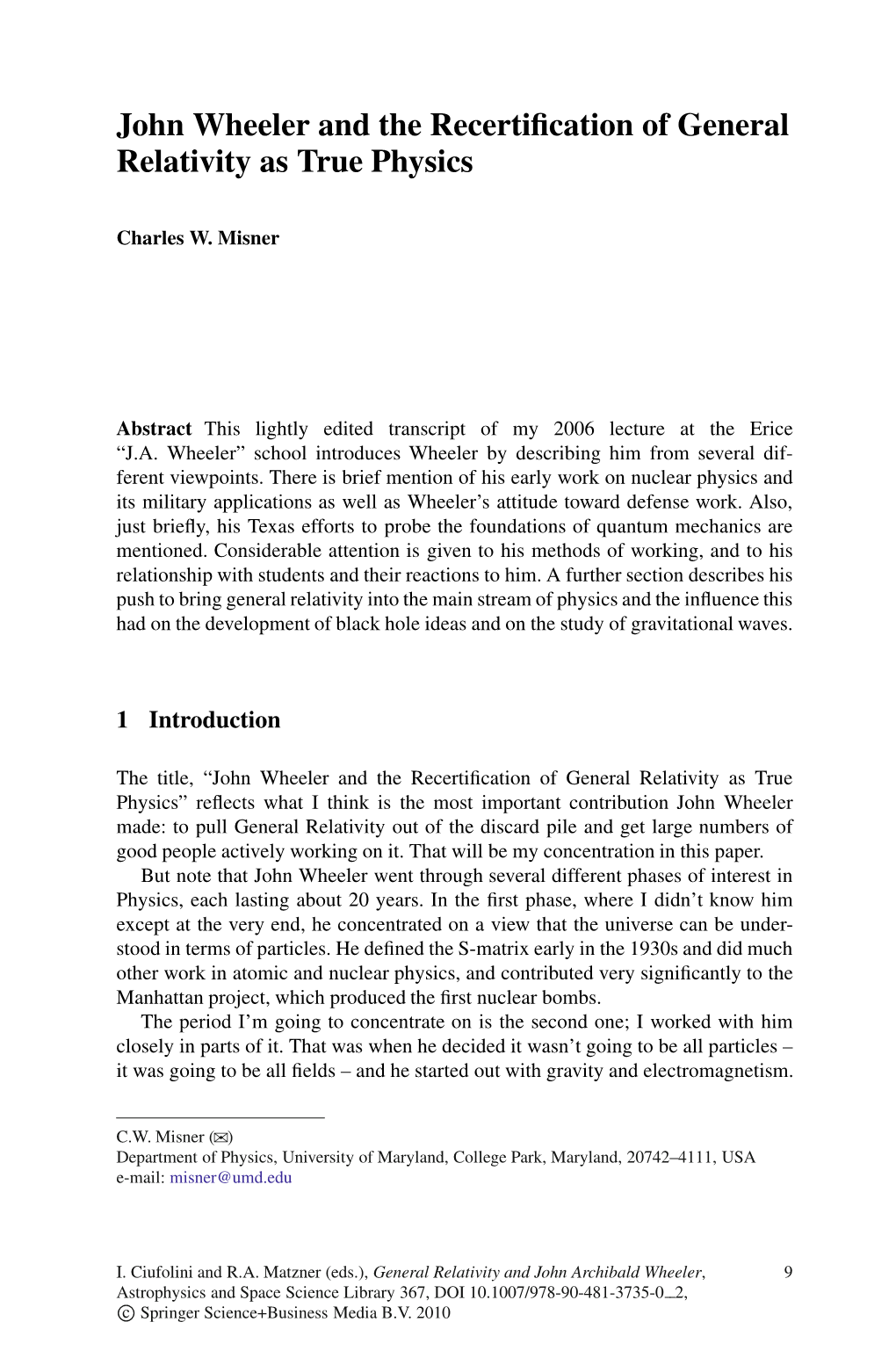

John Wheeler and the Recertification of General Relativity As True Physics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pursuit of Quantum Gravity

The Pursuit of Quantum Gravity Cécile DeWitt-Morette The Pursuit of Quantum Gravity Memoirs of Bryce DeWitt from 1946 to 2004 123 Cécile DeWitt-Morette Department of Physics Center for Relativity University of Texas at Austin Austin Texas USA [email protected] ISBN 978-3-642-14269-7 e-ISBN 978-3-642-14270-3 DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-14270-3 Springer Heidelberg Dordrecht London New York Library of Congress Control Number: 2011921724 c Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2011 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is con- cerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilm or in any other way, and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publica- tion or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9, 1965, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Violations are liable to prosecution under the German Copyright Law. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protec- tive laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. Cover design:WMXDesignGmbH,Heidelberg Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com) Dedicated to our daughters, Nicolette, Jan, Christiane, Abigail Preface This book is written for the curious reader. I hope it will also be a good read for the professional physicist. -

Orbital Resonances and GPU Acceleration of Binary Black Hole Inspiral Simulations

Orbital resonances and GPU acceleration of binary black hole inspiral simulations by Adam Gabriel Marcel Lewis A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Physics University of Toronto c Copyright 2018 by Adam Gabriel Marcel Lewis Abstract Orbital resonances and GPU acceleration of binary black hole inspiral simulations Adam Gabriel Marcel Lewis Doctor of Philosophy Department of Physics University of Toronto 2018 Numerical relativity, the direct numerical integration of the Einstein field equations, is now a mature subfield of computational physics, playing a critical role in the generation of signal templates for comparison with data from ground-based gravitational wave de- tectors. The application of numerical relativity techniques to new problems is at present complicated by long wallclock times and intricate code. In this thesis we lay groundwork to improve this situation by presenting a GPU port of the numerical relativity code SpEC. Our port keeps code maintenance feasible by relying on various layers of automation, and achieves high performance across a variety of GPUs. We secondly introduce a C++ soft- ware package, TLoops, which allows numerical manipulation of tensors using single-line C++ source-code expressions resembling familiar tensor calculus notation. These expres- sions may be compiled and executed immediately, but also can be used to automatically generate equivalent GPU or low-level CPU code, which then executes in their place. The GPU code in particular achieves near-peak performance. Finally, we present simulations of eccentric binary black holes. We develop new methods to extract the fundamental fre- quencies of these systems. -

Comments on the 2011 Shaw Prize in Mathematical Sciences - - an Analysis of Collectively Formed Errors in Physics by C

Global Journal of Science Frontier Research Physics and Space Science Volume 12 Issue 4 Version 1.0 June 2012 Type : Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-4626 & Print ISSN: 0975-5896 Comments on the 2011 Shaw Prize in Mathematical Sciences - - An Analysis of Collectively Formed Errors in Physics By C. Y. Lo Applied and Pure Research Institute, Nashua, NH Abstract - The 2011 Shaw Prize in mathematical sciences is shared by Richard S. Hamilton and D. Christodoulou. However, the work of Christodoulou on general relativity is based on obscure errors that implicitly assumed essentially what is to be proved, and thus gives misleading results. The problem of Einstein’s equation was discovered by Gullstrand of the 1921 Nobel Committee. In 1955, Gullstrand is proven correct. The fundamental errors of Christodoulou were due to his failure to distinguish the difference between mathematics and physics. His subsequent errors in mathematics and physics were accepted since judgments were based not on scientific evidence as Galileo advocates, but on earlier incorrect speculations. Nevertheless, the Committee for the Nobel Prize in Physics was also misled as shown in their 1993 press release. Here, his errors are identified as related to accumulated mistakes in the field, and are illustrated with examples understandable at the undergraduate level. Another main problem is that many theorists failed to understand the principle of causality adequately. It is unprecedented to award a prize for mathematical errors. Keywords : Nobel Prize; general relativity; Einstein equation, Riemannian Space; the non- existence of dynamic solution; Galileo. GJSFR-A Classification : 04.20.-q, 04.20.Cv Comments on the 2011 Shaw Prize in Mathematical Sciences -- An Analysis of Collectively Formed Errors in Physics Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of : © 2012. -

New Publications Offered by The

New Publications Offered by the AMS To subscribe to email notification of new AMS publications, please go to www.ams.org/bookstore-email. Algebra and Algebraic Geometry theorem in noncommutative geometry; M. Guillemard, An overview of groupoid crossed products in dynamical systems. Contemporary Mathematics, Volume 676 Noncommutative November 2016, 222 pages, Softcover, ISBN: 978-1-4704-2297-4, LC 2016017993, 2010 Mathematics Subject Classification: 00B25, 46L87, Geometry and Optimal 58B34, 53C17, 46L60, AMS members US$86.40, List US$108, Order Transport code CONM/676 Pierre Martinetti, Università di Genova, Italy, and Jean-Christophe Wallet, CNRS, Université Paris-Sud 11, Orsay, France, Editors Differential Equations This volume contains the proceedings of the Workshop on Noncommutative Geometry and Optimal Transport, held on November 27, 2014, in Shock Formation in Besançon, France. The distance formula in noncommutative geometry was introduced Small-Data Solutions to by Connes at the end of the 1980s. It is a generalization of Riemannian 3D Quasilinear Wave geodesic distance that makes sense in a noncommutative setting, and provides an original tool to study the geometry of the space of Equations states on an algebra. It also has an intriguing echo in physics, for it yields a metric interpretation for the Higgs field. In the 1990s, Jared Speck, Massachusetts Rieffel noticed that this distance is a noncommutative version of the Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Wasserstein distance of order 1 in the theory of optimal transport. MA More exactly, this is a noncommutative generalization of Kantorovich dual formula of the Wasserstein distance. Connes distance thus offers In 1848 James Challis showed that an unexpected connection between an ancient mathematical problem smooth solutions to the compressible and the most recent discovery in high energy physics. -

Defining Physics at Imaginary Time: Reflection Positivity for Certain

Defining physics at imaginary time: reflection positivity for certain Riemannian manifolds A thesis presented by Christian Coolidge Anderson [email protected] (978) 204-7656 to the Department of Mathematics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an honors degree. Advised by Professor Arthur Jaffe. Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts March 2013 Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Axiomatic quantum field theory 2 3 Definition of reflection positivity 4 4 Reflection positivity on a Riemannian manifold M 7 4.1 Function space E over M ..................... 7 4.2 Reflection on M .......................... 10 4.3 Reflection positive inner product on E+ ⊂ E . 11 5 The Osterwalder-Schrader construction 12 5.1 Quantization of operators . 13 5.2 Examples of quantizable operators . 14 5.3 Quantization domains . 16 5.4 The Hamiltonian . 17 6 Reflection positivity on the level of group representations 17 6.1 Weakened quantization condition . 18 6.2 Symmetric local semigroups . 19 6.3 A unitary representation for Glor . 20 7 Construction of reflection positive measures 22 7.1 Nuclear spaces . 23 7.2 Construction of nuclear space over M . 24 7.3 Gaussian measures . 27 7.4 Construction of Gaussian measure . 28 7.5 OS axioms for the Gaussian measure . 30 8 Reflection positivity for the Laplacian covariance 31 9 Reflection positivity for the Dirac covariance 34 9.1 Introduction to the Dirac operator . 35 9.2 Proof of reflection positivity . 38 10 Conclusion 40 11 Appendix A: Cited theorems 40 12 Acknowledgments 41 1 Introduction Two concepts dominate contemporary physics: relativity and quantum me- chanics. They unite to describe the physics of interacting particles, which live in relativistic spacetime while exhibiting quantum behavior. -

[email protected] PROF. REMO RUFFINI and PROF. ROY

PROF. REMO RUFFINI AND PROF. ROY PATRICK KERR PRESENT THE LATEST RESULTS OF ICRANET RESEARCH TO PROF. STEPHEN HAWKING IN CAMBRIDGE, ENGLAND, AT THE INSTITUTE DAMTP AND AT THE INSTITUTE OF ASTRONOMY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE IN ENGLAND Professor Remo Ruffini, Director of ICRANet, and Professor Roy Patrick Kerr, the discoverer of the world famous "Black Hole Kerr metric" and appointed professor “Yevgeny Mikhajlovic Lifshitz - ICRANet Chair”, have had a 4 days intensive meeting at the University of Cambridge, both at DAMTP and at the Institute of Astronomy, with Professor Stephen Hawking (see photos: 1, 2 e 3) and the resident scientists: they illustrated recent progress made by scientists of ICRANet. The presentation, can be seen on www.icranet.org/documents/Ruffini-Cambridge2017.pdf, includes: - GRB 081024B and GRB 140402A: two additional short GRBs from binary neutron star mergers, by Y. Aimuratov, R. Ruffini, M. Muccino, et al.; Ap.J in press. This ICRANet activity presents the evidence of two new short gamma-ray bursts (S-GRBs) from the mergers of neutron stars binaries forming a Kerr black hole. The existence of a common GeV emission precisely following the black hole formation has been presented. Yerlan Aimuratov is a young scientist from the ICRANet associated University in Alamaty Kazakistan. A free-available version of the article can be found on: https://arXiv.org/abs/1704.08179 - X-ray Flares in Early Gamma-ray Burst Afterglow, by R. Ruffini, Y. Wang, Y. Aimuratov, et al.; Ap.J submitted. This work analyses the early X-ray flares, followed by a "plateau" and then by the late decay of the X-ray afterglow, ("flare-plateau-afterglow phase") observed by Swift-XRT. -

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Reflection Positivity

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Report No. 55/2017 DOI: 10.4171/OWR/2017/55 Reflection Positivity Organised by Arthur Jaffe, Harvard Karl-Hermann Neeb, Erlangen Gestur Olafsson, Baton Rouge Benjamin Schlein, Z¨urich 26 November – 2 December 2017 Abstract. The main theme of the workshop was reflection positivity and its occurences in various areas of mathematics and physics, such as Representa- tion Theory, Quantum Field Theory, Noncommutative Geometry, Dynamical Systems, Analysis and Statistical Mechanics. Accordingly, the program was intrinsically interdisciplinary and included talks covering different aspects of reflection positivity. Mathematics Subject Classification (2010): 17B10, 22E65, 22E70, 81T08. Introduction by the Organisers The workshop on Reflection Positivity was organized by Arthur Jaffe (Cambridge, MA), Karl-Hermann Neeb (Erlangen), Gestur Olafsson´ (Baton Rouge) and Ben- jamin Schlein (Z¨urich) during the week November 27 to December 1, 2017. The meeting was attended by 53 participants from all over the world. It was organized around 24 lectures each of 50 minutes duration representing major recent advances or introducing to a specific aspect or application of reflection positivity. The meeting was exciting and highly successful. The quality of the lectures was outstanding. The exceptional atmosphere of the Oberwolfach Institute provided the optimal environment for bringing people from different areas together and to create an atmosphere of scientific interaction and cross-fertilization. In particular, people from different subcommunities exchanged ideas and this lead to new col- laborations that will probably stimulate progress in unexpected directions. 3264 Oberwolfach Report 55/2017 Reflection positivity (RP) emerged in the early 1970s in the work of Osterwalder and Schrader as one of their axioms for constructive quantum field theory ensuring the equivalence of their euclidean setup with Wightman fields. -

Partial Differential Equations

CALENDAR OF AMS MEETINGS THIS CALENDAR lists all meetings which have been approved by the Council pnor to the date this issue of the Nouces was sent to press. The summer and annual meetings are joint meetings of the Mathematical Association of America and the Ameri· can Mathematical Society. The meeting dates which fall rather far in the future are subject to change; this is particularly true of meetings to which no numbers have yet been assigned. Programs of the meetings will appear in the issues indicated below. First and second announcements of the meetings will have appeared in earlier issues. ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS presented at a meeting of the Society are published in the journal Abstracts of papers presented to the American Mathematical Society in the issue corresponding to that of the Notices which contains the program of the meet ing. Abstracts should be submitted on special forms which are available in many departments of mathematics and from the office of the Society in Providence. Abstracts of papers to be presented at the meeting must be received at the headquarters of the Society in Providence, Rhode Island, on or before the deadline given below for the meeting. Note that the deadline for ab stracts submitted for consideration for presentation at special sessions is usually three weeks earlier than that specified below. For additional information consult the meeting announcement and the list of organizers of special sessions. MEETING ABSTRACT NUMBER DATE PLACE DEADLINE ISSUE 778 June 20-21, 1980 Ellensburg, Washington APRIL 21 June 1980 779 August 18-22, 1980 Ann Arbor, Michigan JUNE 3 August 1980 (84th Summer Meeting) October 17-18, 1980 Storrs, Connecticut October 31-November 1, 1980 Kenosha, Wisconsin January 7-11, 1981 San Francisco, California (87th Annual Meeting) January 13-17, 1982 Cincinnati, Ohio (88th Annual Meeting) Notices DEADLINES ISSUE NEWS ADVERTISING June 1980 April 18 April 29 August 1980 June 3 June 18 Deadlines for announcements intended for the Special Meetings section are the same as for News. -

Global Program

PROGRAM Monday morning, July 13th La Sapienza Roma - Aula Magna 09:00 - 10:00 Inaugural Session Chairperson: Paolo de Bernardis Welcoming addresses Remo Ruffini (ICRANet), Yvonne Choquet-Bruhat (French Académie des Sciences), Jose’ Funes (Vatican City), Ricardo Neiva Tavares (Ambassador of Brazil), Sargis Ghazaryan (Ambassador of Armenia), Francis Everitt (Stanford University) and Chris Fryer (University of Arizona) Marcel Grossmann Awards Yakov Sinai, Martin Rees, Sachiko Tsuruta, Ken’Ichi Nomoto, ESA (acceptance speech by Johann-Dietrich Woerner, ESA Director General) Lectiones Magistrales Yakov Sinai (Princeton University) 10:00 - 10:35 Deterministic chaos Martin Rees (University of Cambridge) 10:35 - 11:10 How our understanding of cosmology and black holes has been revolutionised since the 1960s 11:10 - 11:35 Group Picture - Coffee Break Gerard 't Hooft (University of Utrecht) 11:35 - 12:10 Local Conformal Symmetry in Black Holes, Standard Model, and Quantum Gravity Plenary Session: Mathematics and GR Katarzyna Rejzner (University of York) 12:10 - 12:40 Effective quantum gravity observables and locally covariant QFT Zvi Bern (UCLA Physics & Astronomy) 12:40 - 13:10 Ultraviolet surprises in quantum gravity 14:30 - 18:00 Parallel Session 18:45 - 20:00 Stephen Hawking (teleconference) (University of Cambridge) Public Lecture Fire in the Equations Monday afternoon, July 13th Code Classroom Title Chairperson AC2 ChN1 MHD processes near compact objects Sergej Moiseenko FF Extended Theories of Gravity and Quantum Salvatore Capozziello, Gabriele AT1 A Cabibbo Cosmology Gionti AT3 A FF3 Wormholes, Energy Conditions and Time Machines Francisco Lobo Localized selfgravitating field systems in the AT4 FF6 Dmitry Galtsov, Michael Volkov Einstein and alternatives theories of gravity BH1:Binary Black Holes as Sources of Pablo Laguna, Anatoly M. -

6. L CPT Reversal

6. CPT reversal l Précis. On the representation view, there may be weak and strong arrows of time. A weak arrow exists. A strong arrow might too, but not in current physics due to CPT symmetry. There are many ways to reverse time besides the time reversal operator T. Writing P for spatial reflection or ‘parity’, and C for matter-antimatter exchange or ‘charge conjugation’, we find that PT, CT, and CPT are all time reversing transformations, when they exist. More generally, for any non-time-reversing (unitary) transformation U, we find that UT is time reversing. Are any of these transformations relevant for the arrow of time? Feynman (1949) captured many of our imaginations with the proposal that to understand the direction of time, we must actually consider the exchange of matter and antimatter as well.1 Writing about it years later, he said: “A backwards-moving electron when viewed with time moving forwards appears the same as an ordinary electron, except it’s attracted to normal electrons — we say it has positive charge. For this reason it’s called a ‘positron’. The positron is a sister to the electron, and it is an example of an ‘anti-particle’. This phenomenon is quite general. Every particle in Nature has an amplitude to move backwards in time, and therefore has an anti-particle.”(Feynman 1985, p.98) Philosophers Arntzenius and Greaves (2009, p.584) have defended Feynman’s proposal, 1In his Nobel prize speech, Feynman (1972, pg.163) attributes this idea to Wheeler in the development of their absorber theory (Wheeler and Feynman 1945). -

Download Report 2010-12

RESEARCH REPORt 2010—2012 MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Cover: Aurora borealis paintings by William Crowder, National Geographic (1947). The International Geophysical Year (1957–8) transformed research on the aurora, one of nature’s most elusive and intensely beautiful phenomena. Aurorae became the center of interest for the big science of powerful rockets, complex satellites and large group efforts to understand the magnetic and charged particle environment of the earth. The auroral visoplot displayed here provided guidance for recording observations in a standardized form, translating the sublime aesthetics of pictorial depictions of aurorae into the mechanical aesthetics of numbers and symbols. Most of the portait photographs were taken by Skúli Sigurdsson RESEARCH REPORT 2010—2012 MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Introduction The Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (MPIWG) is made up of three Departments, each administered by a Director, and several Independent Research Groups, each led for five years by an outstanding junior scholar. Since its foundation in 1994 the MPIWG has investigated fundamental questions of the history of knowl- edge from the Neolithic to the present. The focus has been on the history of the natu- ral sciences, but recent projects have also integrated the history of technology and the history of the human sciences into a more panoramic view of the history of knowl- edge. Of central interest is the emergence of basic categories of scientific thinking and practice as well as their transformation over time: examples include experiment, ob- servation, normalcy, space, evidence, biodiversity or force. -

![Arxiv:Physics/0608067V1 [Physics.Hist-Ph] 7 Aug 2006 N I Olbrtr Ntepro Rm14 O1951](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0136/arxiv-physics-0608067v1-physics-hist-ph-7-aug-2006-n-i-olbrtr-ntepro-rm14-o1951-770136.webp)

Arxiv:Physics/0608067V1 [Physics.Hist-Ph] 7 Aug 2006 N I Olbrtr Ntepro Rm14 O1951

Peter Bergmann and the invention of constrained Hamiltonian dynamics D. C. Salisbury Department of Physics, Austin College, Sherman, Texas 75090-4440, USA E-mail: [email protected] (Dated: July 23, 2006) Abstract Peter Bergmann was a co-inventor of the algorithm for converting singular Lagrangian models into a constrained Hamiltonian dynamical formalism. This talk focuses on the work of Bergmann and his collaborators in the period from 1949 to 1951. arXiv:physics/0608067v1 [physics.hist-ph] 7 Aug 2006 1 INTRODUCTION It has always been the practice of those of us associated with the Syracuse “school” to identify the algorithm for constructing a canonical phase space description of singular La- grangian systems as the Dirac-Bergmann procedure. I learned the procedure as a student of Peter Bergmann - and I should point out that he never employed that terminology. Yet it was clear from the published record at the time in the 1970’s that his contribution was essential. Constrained Hamiltonian dynamics constitutes the route to canonical quantiza- tion of all local gauge theories, including not only conventional general relativity, but also grand unified theories of elementary particle interaction, superstrings and branes. Given its importance and my suspicion that Bergmann has never received adequate recognition from the wider community for his role in the development of the technique, I have long intended to explore this history in depth. The following is merely a tentative first step in which I will focus principally on the work of Peter Bergmann and his collaborators in the late 1940’s and early 1950’s, indicating where appropriate the relation of this work to later developments.