Pawn Shop”: a Field Experiment to Study WTA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glitz and Glam

FINAL-1 Sat, Feb 24, 2018 5:31:17 PM Glitz and glam The biggest celebration in filmmaking tvspotlight returns with the 90th Annual Academy Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment Awards, airing Sunday, March 4, on ABC. Every year, the most glamorous people • For the week of March 3 - 9, 2018 • in Hollywood stroll down the red carpet, hoping to take home that shiny Oscar for best film, director, lead actor or ac- tress and supporting actor or actress. Jimmy Kimmel returns to host again this year, in spite of last year’s Best Picture snafu. OMNI Security Team Jimmy Kimmel hosts the 90th Annual Academy Awards Omni Security SERVING OUR COMMUNITY FOR OVER 30 YEARS Put Your Trust in Our2 Familyx 3.5” to Protect Your Family Big enough to Residential & serve you Fire & Access Commercial Small enough to Systems and Video Security know you Surveillance Remote access 24/7 Alarm & Security Monitoring puts you in control Remote Access & Wireless Technology Fire, Smoke & Carbon Detection of your security Personal Emergency Response Systems system at all times. Medical Alert Systems 978-465-5000 | 1-800-698-1800 | www.securityteam.com MA Lic. 444C Old traditional Italian recipes made with natural ingredients, since 1995. Giuseppe's 2 x 3” fresh pasta • fine food ♦ 257 Low Street | Newburyport, MA 01950 978-465-2225 Mon. - Thur. 10am - 8pm | Fri. - Sat. 10am - 9pm Full Bar Open for Lunch & Dinner FINAL-1 Sat, Feb 24, 2018 5:31:19 PM 2 • Newburyport Daily News • March 3 - 9, 2018 the strict teachers at her Cath- olic school, her relationship with her mother (Metcalf) is Videoreleases strained, and her relationship Cream of the crop with her boyfriend, whom she Thor: Ragnarok met in her school’s theater Oscars roll out the red carpet for star quality After his father, Odin (Hop- program, ends when she walks kins), dies, Thor’s (Hems- in on him kissing another guy. -

To View & Download My Resume

NAWARA BLUE Producer Driven, organized, detail- WORK EXPERIENCE oriented, and creative professional with extensive Roll Up Your Sleeves (2021 COVID Vaccination Special)- Producer NBC/ Camouflage Films, Inc. (Houston, TX) experience in television production. Skillset includes Put A Ring On It (Season 2)- Supervising Field Producer cultivating stories, tracking OWN / Lighthearted ENT (Atlanta, GA) multiple storylines, producing and directing large cast. Skilled Ready to Love (Season 4)- Supervising Field Producer OWN / Lighthearted ENT (Houston, TX) in talent and crew management, control room and Self Employed (Pilot)- Supervising Field Producer floor producing, and directing Magnolia / Red Productions (Dallas, TX) multiple cameras. Experienced in conducting and writing formal Supa Girlz (Season 1 Documentary)- Supervising Field Producer interviews and OTFs. Proficient in HBO MAX / Film-45 (Miami, FL) scheduling, budgeting, casting, Bride & Prejudice (Season 2)- Supervising Producer clearing locations, writing hot TLC/ Kinetic Content (Atlanta, GA) sheets, outlines, beat sheets, creative decks, show bibles, and Little Women Atlanta (Season 6)- Senior Field Producer any other pertinent production Lifetime/ Kinetic Content (Atlanta, GA) documents. Look Me in The Eye (Pilot)- Senior Field Producer OWN/ Kinetic Content (Los Angeles, CA) Digital proficiencies include Microsoft Office, Google Drive, The American Barbeque Showdown (Season 1)- Field Producer and Social Media platforms. Netflix/ All 3 Media (Atlanta, GA) Love Is Blind (Season 1)- Field Producer EDUCATION Netflix/ Delirium TV, LLC (Atlanta, GA) WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY, DETROIT MI 2006-2010 Teen Mom 2 (Season 16)- Field Producer Bachelor of Arts, Public Relations MTV/ MTV (Orlando, FL) Member of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority Inc. Beta Mu Chapter Married at First Sight: Honeymoon Island (Season 1)- Field Producer Lifetime/ Kinetic Content (Los Angeles, CA & St. -

Pawn Stars: Putting Theories of Negotiation to the Test

European Journal of Contemporary Economics and Management December 2014 Edition Vol.1 No.2 PAWN STARS: PUTTING THEORIES OF NEGOTIATION TO THE TEST Bryan C. Mc Cannon, PhD John Stevens,M.A. Saint Bonaventure University, U.S.A. Doi: 10.19044/elp.v1no2a4 URL:http://dx.doi.org/10.19044/elp.v1no2a4 Abstract Theories of negotiations are tested using a unique data set. The History Channel television show Pawn Stars portrays negotiations between customers and agents of a pawn shop. This provides a novel data set not typically available to researchers as the tactics of bargaining can be observed, recorded, and analyzed. Many, but not all, of the primary theories of negotiations developed receive empirical support. The use of experts, experience of the negotiators, the gap between the initial offers, and the use of final offers all affect the likelihood of a deal being made as well as the division of the surplus. The party making the opening offer suffers a disadvantage, which stands in contrast to predictions of sequential bargaining and anchoring effects. Keywords: Asymmetric information, bargaining, experts, final offer, negotiation, Pawn Stars Introduction Negotiating is a central activity within any organization. A systematic evaluation of the success of the methods used and the environment within which negotiations are taking place must be developed. To be able to formulate and implement successful strategies, an organization must appreciate the effectiveness of the process involved. Previous management research focuses on the relationship between the bargaining process and outcomes. Wall (1984) investigates, for example, the impact of mediator proposals on bargaining outcomes. -

You Can Bet on That TV Listings 2014-12-17 Through 2014-12-30

You Can Bet on That TV Listings 2014-12-17 through 2014-12-30 All times are Eastern or Eastern/Pacific. Movie ratings are from one to four stars. New shows are highlighted in green. 2014 World Series of Poker From Las Vegas. Sports event, Series, 60 min. SUN, DEC 28, 2014, 4:00 PM ESPN SUN, DEC 28, 2014, 8:00 PM ESPN2 SUN, DEC 28, 2014, 9:00 PM ESPN2 2014 World Series of Poker "Final Table" From Las Vegas. Sports event, Series, 120 min. SUN, DEC 28, 2014, 5:00 PM ESPN SUN, DEC 28, 2014, 10:00 PM ESPN2 2014 World Series of Poker APAC From Melbourne, Australia. Sports event, Series, 60 min. SUN, DEC 21, 2014, 8:00 PM ESPN2 SUN, DEC 21, 2014, 9:00 PM ESPN2 SUN, DEC 21, 2014, 10:00 PM ESPN2 SUN, DEC 21, 2014, 11:00 PM ESPN2 21 Students (Jim Sturgess, Kate Bosworth) from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology become experts at card-counting and use the skill to win big at Las Vegas casinos. Drama, Movie (2008 ★★½), 150 min. TUE, DEC 23, 2014, 6:30 PM Esquire TUE, DEC 23, 2014, 11:00 PM Esquire 90 Day Fiance "I'm Gonna Go Home" Chelsea panics before her wedding; Jason and Cassia try to fix their relationship problems in Las Vegas; Mohamed goes missing on Danielle; Brett has to choose between his mother and Daya. Reality, Series, 60 min. SUN, DEC 21, 2014, 9:00 PM TLC SUN, DEC 21, 2014, 11:01 PM TLC THU, DEC 25, 2014, 10:00 PM TLC FRI, DEC 26, 2014, 12:00 AM TLC SUN, DEC 28, 2014, 8:00 PM TLC MON, DEC 29, 2014, 2:00 AM TLC American Greed "The Tran Organization: Blackjack Cheaters" Van Thu Tran and her crime ring steal millions by cheating casinos. -

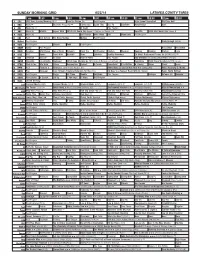

Sunday Morning Grid 6/22/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/22/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program High School Basketball PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Justin Time Tree Fu LazyTown Auto Racing Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Wildlife Exped. Wild 2014 FIFA World Cup Group H Belgium vs. Russia. (N) SportCtr 2014 FIFA World Cup: Group H 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Program Crazy Enough (2012) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Paid Program RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Wild Places Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Kitchen Lidia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News LinkAsia Healthy Hormones Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program Into the Blue ›› (2005) Paul Walker. (PG-13) 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Backyard 2014 Copa Mundial de FIFA Grupo H Bélgica contra Rusia. (N) República 2014 Copa Mundial de FIFA: Grupo H 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Harvest In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio Austria. -

Tv Pg 6 3-2.Indd

6 The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, March 2, 2009 All Mountain Time, for Kansas Central TIme Stations subtract an hour TV Channel Guide Tuesday Evening March 2, 2010 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 28 ESPN 57 Cartoon Net 21 TV Land 41 Hallmark ABC Lost Lost 20/20 Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live S&T Eagle CBS NCIS NCIS: Los Angeles The Good Wife Local Late Show Letterman Late 29 ESPN 2 58 ABC Fam 22 ESPN 45 NFL NBC The Biggest Loser Parenthood Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late 2 PBS KOOD 2 PBS KOOD 23 ESPN 2 47 Food FOX American Idol Local 30 ESPN Clas 59 TV Land Cable Channels 3 KWGN WB 31 Golf 60 Hallmark 3 NBC-KUSA 24 ESPN Nws 49 E! A&E Criminal Minds CSI: Miami CSI: Miami Criminal Minds Local 5 KSCW WB 4 ABC-KLBY AMC To-Mockingbird To-Mockingbird Local 32 Speed 61 TCM 25 TBS 51 Travel ANIM 6 Weather Wild Recon Madman of the Sea Wild Recon Untamed and Uncut Madman Local 6 ABC-KLBY 33 Versus 62 AMC 26 Animal 54 MTV BET National Security Vick Tiny-Toya The Mo'Nique Show Wendy Williams Show Security Local 7 CBS-KBSL BRAVO Mill. Matchmaker Mill. Matchmaker Mill. Matchmaker Mill. Matchmaker Matchmaker 7 KSAS FOX 34 Sportsman 63 Lifetime 27 VH1 55 Discovery CMT Local Local Smarter Smarter Extreme-Home O Brother, Where Art 8 NBC-KSNK 8 NBC-KSNK 28 TNT 56 Fox Nws CNN 35 NFL 64 Oxygen Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live Anderson Local 9 Eagle COMEDY S. -

Recovering Six Nations' Heritage in Wampums by Stephanie Dearing Explaining His Wife Had Giv Torian Keith Jamieson

Recovering Six Nations' heritage in wampums By Stephanie Dearing explaining his wife had giv torian Keith Jamieson. SIX NATIONS en him instructions to sell But while price presents the plate at a certain price. a rather large stumbling Watching a silver breast The breast plate had been in block, it's one of the least plate, originally given to Six his wife's family for some problems in bringing some Nations by the British dur time, he said. His wife's thing back to where it right ing the negotiations of the mother was a Blackfoot. fully belongs. 1784 Fort Stanwix Treaty, The Silver Dollar shop "The problem is, we don't being sold to a pawn shop owners had an expert come know how they [the seller] featured on the popular tele in to appraise the breast got it," said Jamieson. "Un vision series, Cajun Pawn plate, which was valued less we can find the prov Stars, shocked Brenda Ma at an estimated $25,000 to enance to it, and it was racle Hill, who wondered if $30,000. According to the stolen and they bought sto the breast plate could be re expert, the plate was giv len property, then we· have covered. en to Six Nations Iroquois a shot. But if it was bought "That's ours," Brenda at Fort Stanwix at the sign legitimately from whoever said, explaining how she ing of the 1874 treaty, which received it, then there's not felt upon realizing the breast took place after the Ameri much you can say." plate was historically signif can War of Independence. -

TV Listings SATURDAY, APRIL 1, 2017

TV listings SATURDAY, APRIL 1, 2017 03:00 Man Fire Food 01:20 The Unexplained Files 03:30 Man Fire Food 02:10 How The Earth Works 04:00 Chopped 03:00 The Big Brain Theory 05:00 Guy's Grocery Games 03:48 Mythbusters 06:00 Roadtrip With G. Garvin 04:36 How Do They Do It? 06:30 Roadtrip With G. Garvin 05:00 Food Factory 07:00 Chopped 05:24 The Unexplained Files 08:00 Barefoot Contessa: Back To Basics 06:12 How The Earth Works 08:30 Barefoot Contessa: Back To Basics 07:00 How Do They Do It? 09:00 The Pioneer Woman 07:26 Food Factory 09:30 The Pioneer Woman 07:50 Food Factory 10:00 Siba's Table 08:14 Food Factory 10:30 Siba's Table 08:38 Food Factory 11:00 Anna Olson: Bake 09:02 Food Factory 11:30 Anna Olson: Bake 09:26 How Do They Do It? 12:00 Man Fire Food 09:50 How Do They Do It? 12:30 Man Fire Food 10:14 How Do They Do It? 13:00 Diners, Drive-Ins And Dives 10:38 How Do They Do It? 13:30 Diners, Drive-Ins And Dives 11:02 How Do They Do It? 14:00 Chopped 11:26 How The Earth Works 15:00 Barefoot Contessa: Back To Basics 12:14 How The Earth Works 15:30 Barefoot Contessa: Back To Basics 13:02 How The Earth Works 16:00 The Pioneer Woman 13:50 How The Earth Works 16:30 The Pioneer Woman 14:38 How The Earth Works 17:00 Siba's Table 15:26 Mythbusters 17:30 Siba's Table 16:14 Mythbusters 18:00 Anna Olson: Bake 17:02 Mythbusters 18:30 Anna Olson: Bake 17:50 Mythbusters 19:00 Man Fire Food 18:40 Mythbusters 19:30 Man Fire Food 19:30 NASA's Unexplained Files 20:00 Diners, Drive-Ins And Dives 20:20 Sport Science 20:30 Diners, Drive-Ins And Dives 21:10 -

Counting Cars

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE HISTORY® Revs Up for More Wheeling and Dealing When Danny ‘The Count’ Koker Returns to the Driver’s Seat for an All-New Season of… COUNTING CARS New York, NY – His name is The Count, and his game is one-of-a-kind, customized classic cars and motorcycles. Danny “The Count” Koker doesn’t just love hot rods and choppers. He lives for them. Whether it’s a ’63 Corvette, a classic Thunderbird, a muscle-bound Trans Am, or a yacht-sized Caddy, he knows these high-performance beauties inside and out. What’s more, he’ll do anything it takes to get his hands on those he likes – he’s known for pulling over cars he passes on the road and offering cash for them on the spot, or for using a retailer’s PA system to lure a car owner back to the parking lot to make a deal – and then “flip” them for a profit. Danny and the crew from Count’s Kustoms, his Vegas-based auto repair business, are behind the wheel again for a new season of COUNTING CARS, premiering Tuesday, April 9 at 9pm ET on HISTORY. The heat is on as the boys buy, trick out and re-sell classic cars, bikes and more. Danny is obsessed, so the more rides he buys, the faster they have to move to keep Count’s Kustoms in business. This season’s projects span all eras of cars, trucks, bikes and trikes. They’ll be working with Ziggy Marley to restore and customize Bob Marley’s last car, a 1980 Mercedes 500SL Euro; and customizing a soap box derby car for a youngster. -

Affidavit of Performance

OnMedia Advertising Sales 1037 Front Avenue Suite C Columbus , GA31901 Affidavit of Performance Client Name VOTER PROTECTION PROJECT-GA Contract ID 292171 Remarks 62851972-3646 Contract Type Political Bill Cycle 12/20 Bill Type Condensed EAI Broadcast Standard Date Weekday Network Zone Program Name Air Time Spot Name Spot Contract Billing Spot Length Line Status Cost 12/10/2020 Thursday FXNC_E Columbus-Valley-Auburn Fox & Friends First 5:22 AM VPP2000H Dress UP 00:00:30 1 Charged 97.00 * 12/10/2020 Thursday FXNC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA Fox and Friends 6:23 AM VPP2000H Dress UP 00:00:30 1 Charged 97.00 * 12/10/2020 Thursday FXNC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA America's Newsroom 9:15 AM VPP2000H Dress UP 00:00:30 1 Charged 97.00 * 12/11/2020 Friday FXNC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA Fox and Friends 6:51 AM VPP2000H Dress UP 00:00:30 1 Charged 97.00 * 12/12/2020 Saturday FXNC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA The Five 5:14 AM VPP2000H Dress UP 00:00:30 1 Charged 97.00 * 12/12/2020 Saturday FXNC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA The Five 5:47 AM VPP2000H Dress UP 00:00:30 1 Charged 97.00 * 12/13/2020 Sunday FXNC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA Fox and Friends 7:23 AM VPP2000H Dress UP 00:00:30 1 Charged 97.00 * 12/13/2020 Sunday FXNC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA Fox and Friends 7:52 AM VPP2000H Dress UP 00:00:30 1 Charged 97.00 * 12/13/2020 Sunday FXNC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA Fox and Friends 8:50 AM VPP2000H Dress UP 00:00:30 1 Charged 97.00 * 12/14/2020 Monday FXNC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA Fox & Friends First 5:21 AM VPP2000H -

DVD List As of 2/9/2013 2 Days in Paris 3 Idiots 4 Film Favorites(Secret

A LIST OF THE NEWEST DVDS IS LOCATED ON THE WALL NEXT TO THE DVD SHELVES DVD list as of 2/9/2013 2 Days in Paris 3 Idiots 4 Film Favorites(Secret Garden, The Witches, The Neverending Story, 5 Children & It) 5 Days of War 5th Quarter, The $5 A Day 8 Mile 9 10 Minute Solution-Quick Tummy Toners 10 Minute Solution-Dance off Fat Fast 10 Minute Solution-Hot Body Boot Camp 12 Men of Christmas 12 Rounds 13 Ghosts 15 Minutes 16 Blocks 17 Again 21 21 Jumpstreet (2012) 24-Season One 25 th Anniversary Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Concerts 28 Weeks Later 30 Day Shred 30 Minutes or Less 30 Years of National Geographic Specials 40-Year-Old-Virgin, The 50/50 50 First Dates 65 Energy Blasts 13 going on 30 27 Dresses 88 Minutes 102 Minutes That Changed America 127 Hours 300 3:10 to Yuma 500 Days of Summer 9/11 Commission Report 1408 2008 Beijing Opening Ceremony 2012 2016 Obama’s America A-Team, The ABCs- Little Steps Abandoned Abandoned, The Abduction About A Boy Accepted Accidental Husband, the Across the Universe Act of Will Adaptation Adjustment Bureau, The Adventures of Sharkboy & Lavagirl in 3-D Adventures of Teddy Ruxpin-Vol 1 Adventures of TinTin, The Adventureland Aeonflux After.Life Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-The Murder of Roger Ackroyd Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Sad Cypress Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-The Hollow Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Five Little Pigs Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Lord Edgeware Dies Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Evil Under the Sun Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Murder in Mespotamia Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Death on the Nile Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Taken at -

TALENT CASTING/DEVELOPMENT a Royal Wedding Special (Snapchat +TLC) Watercooler Casting

TALENT CASTING/DEVELOPMENT A Royal Wedding Special (Snapchat +TLC) Watercooler Casting Group 9 Drag Me Down The Aisle (TLC) Watercooler Casting ALXEMY X Casting & Host Development Watercooler Casting Group 9-Thrillist, Dodo, & Seeker Trekenomics & Snow Day Watercooler Casting Travel Channel Ancient Beasts (Travel Channel) Watercooler Casting Arrow Media Gatherings (Reese Witherspoon/WT) Watercooler Casting Part2Pictures In Bed With Simon Watercooler Casting FYI A Mans World (Bravo) Watercooler Casting Lucky 8 Zooborns (Animal Planet) Watercooler Casting MY Entertainment Ice Age Live (Animal Planet) Watercooler Casting Renegade Times Square 24/7 (Travel Channel) Watercooler Casting Departure Films Love Sick (Lifetime) Watercooler Casting Big Apple Productions Blind Partners (Spike) Watercooler Casting Blackfin Teenprenuer (Lifetime) Watercooler Casting Lincoln Square Studios Miami Flips (Gabrielle Union/HGTV) Watercooler Casting Deaprture Films A&E Character PitchFest 2016 Watercooler Casting A&E Networks Mysteries of Jamaica Watercooler Casting Switchblade Entertainment WT “Swirled” (VH1) Watercooler Casting Left/Right & Superb Entertainment “Planes, Trains, and Automobiles” (Travel) Watercooler Casting Switchblade Entertainment “Sh*t We Don’t Talk About” (Science Channel) Watercooler Casting MY Entertainment “My Crazy Kids” (TLC) Watercooler Casting Back2Back “The Audience” (Bravo) Watercooler Casting ITV “Amazon Women” (Lifetime) Watercooler Casting Watercooler Casting/Mike TV “Autopsy Girls” (Oxygen) Watercooler Casting GRB Multiple Development Project(s) Watercooler Casting ITV (Consulting/Retainer) Untitled DIY Development Project Watercooler Casting Back Roads Entertainment “Restorative Justice” (A&E) Watercooler Casting Citizen Jones 2015 Spike Casting Pitch Fest Watercooler Casting Spike “Coming to America” (BBC) Watercooler Casting Voltage TV “Unlisted” (ABC Family) Watercooler Casting Lincoln Studios “Reaching For Heaven” (Oxygen) Watercooler Casting EOne “Boots of Glory” (Tru) Watercooler Casting Jane St.