Three Who Made It!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview with Edith Wyle, 1993 March 9-September 7

Oral history interview with Edith Wyle, 1993 March 9-September 7 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Interview EW: EDITH WYLE SE: SHARON EMANUELLI SE: This is an interview for the Archives of American Art, the Smithsonian Institution. The interview is with Edith R. Wyle, on March 9th, Tuesday, 1993, at Mrs. Wyle's home in the Brentwood area of Los Angeles. The interviewer is Sharon K. Emanuelli. This is Tape 1, Side A. Okay, Edith, we're going to start talking about your early family background. EW: Okay. SE: What's your birth date and place of birth? EW: Place of birth, San Francisco. Birth date, are you ready for this? April 21st, 1918-though next to Beatrice [Wood-Ed.] that doesn't seem so old. SE: No, she's having her 100th birthday, isn't she? EW: Right. SE: Tell me about your grandparents. I guess it's your maternal grandparents that are especially interesting? EW: No, they all were. I mean, if you'd call that interesting. They were all anarchists. They came from Russia. SE: Together? All together? EW: No, but they knew each other. There was a group of Russians-Lithuanians and Russians-who were all revolutionaries that came over here from Russia, and they considered themselves intellectuals and they really were self-educated, but they were very learned. -

Annual Report 2018–2019 Artmuseum.Princeton.Edu

Image Credits Kristina Giasi 3, 13–15, 20, 23–26, 28, 31–38, 40, 45, 48–50, 77–81, 83–86, 88, 90–95, 97, 99 Emile Askey Cover, 1, 2, 5–8, 39, 41, 42, 44, 60, 62, 63, 65–67, 72 Lauren Larsen 11, 16, 22 Alan Huo 17 Ans Narwaz 18, 19, 89 Intersection 21 Greg Heins 29 Jeffrey Evans4, 10, 43, 47, 51 (detail), 53–57, 59, 61, 69, 73, 75 Ralph Koch 52 Christopher Gardner 58 James Prinz Photography 76 Cara Bramson 82, 87 Laura Pedrick 96, 98 Bruce M. White 74 Martin Senn 71 2 Keith Haring, American, 1958–1990. Dog, 1983. Enamel paint on incised wood. The Schorr Family Collection / © The Keith Haring Foundation 4 Frank Stella, American, born 1936. Had Gadya: Front Cover, 1984. Hand-coloring and hand-cut collage with lithograph, linocut, and screenprint. Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960 / © 2017 Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 12 Paul Wyse, Canadian, born United States, born 1970, after a photograph by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, American, born 1952. Toni Morrison (aka Chloe Anthony Wofford), 2017. Oil on canvas. Princeton University / © Paul Wyse 43 Sally Mann, American, born 1951. Under Blueberry Hill, 1991. Gelatin silver print. Museum purchase, Philip F. Maritz, Class of 1983, Photography Acquisitions Fund 2016-46 / © Sally Mann, Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery © Helen Frankenthaler Foundation 9, 46, 68, 70 © Taiye Idahor 47 © Titus Kaphar 58 © The Estate of Diane Arbus LLC 59 © Jeff Whetstone 61 © Vesna Pavlovic´ 62 © David Hockney 64 © The Henry Moore Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 65 © Mary Lee Bendolph / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York 67 © Susan Point 69 © 1973 Charles White Archive 71 © Zilia Sánchez 73 The paper is Opus 100 lb. -

Valeska Soares B

National Museum of Women in the Arts Selections from the Collection Large-Print Object Labels As of 8/11/2020 1 Table of Contents Instructions…………………………………………………..3 Rotunda……………………………………………………….4 Long Gallery………………………………………………….5 Great Hall………………….……………………………..….18 Mezzanine and Kasser Board Room…………………...21 Third Floor…………………………………………………..38 2 National Museum of Women in the Arts Selections from the Collection Large-Print Object Labels The large-print guide is ordered presuming you enter the third floor from the passenger elevators and move clockwise around each gallery, unless otherwise noted. 3 Rotunda Loryn Brazier b. 1941 Portrait of Wilhelmina Cole Holladay, 2006 Oil on canvas Gift of the artist 4 Long Gallery Return to Nature Judith Vejvoda b. 1952, Boston; d. 2015, Dixon, New Mexico Garnish Island, Ireland, 2000 Toned silver print National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Susan Fisher Sterling Top: Ruth Bernhard b. 1905, Berlin; d. 2006, San Francisco Apple Tree, 1973 Gelatin silver print National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift from the Trustees of the Corcoran Gallery of Art (Gift of Sharon Keim) 5 Bottom: Ruth Orkin b. 1921, Boston; d. 1985, New York City Untitled, ca. 1950 Gelatin silver print National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Joel Meyerowitz Mwangi Hutter Ingrid Mwangi, b. 1975, Nairobi; Robert Hutter, b. 1964, Ludwigshafen am Rhein, Germany For the Last Tree, 2012 Chromogenic print National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Tony Podesta Collection Ecological concerns are a frequent theme in the work of artist duo Mwangi Hutter. Having merged names to identify as a single artist, the duo often explores unification 6 of contrasts in their work. -

The Materiality of Text and Body in Painting and Darkroom Processes: an Investigation Through Practice

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2003 The Materiality of Text and Body in Painting and Darkroom Processes: An Investigation through Practice Robinson, Deborah http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/1738 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. The Materiality of Text and Body in Painting and Darkroom Processes: An Investigation through Practice by Deborah Robinson A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Art and Design Faculty of Arts and Education June 2003 The Materiality of Text and Body in Painting and Darkroom Processes: An Investigation through Practice Deborah Claire Robinson This research study ennploys practice-based strategies through which material processes might be opened to new meaning in relation to the feminine. The purpose of the written research component is to track the material processes constituting a significant part of the research findings. Beginning with historical research into artistic and critical responses to Helen Frankenthaler's painting, Mountains and Sea, I argue that unacknowledged male desire distorted and consequently marginalised reception of her work. I then work with the painting processes innovated by Frankenthaler and relate these to a range of feminist ideas relating to the corporeal, especially those with origins in Irigaray's writings of the 1980s. -

Double Vision: Woman As Image and Imagemaker

double vision WOMAN AS IMAGE AND IMAGEMAKER Everywhere in the modern world there is neglect, the need to be recognized, which is not satisfied. Art is a way of recognizing oneself, which is why it will always be modern. -------------- Louise Bourgeois HOBART AND WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES The Davis Gallery at Houghton House Sarai Sherman (American, 1922-) Pas de Deux Electrique, 1950-55 Oil on canvas Double Vision: Women’s Studies directly through the classes of its Woman as Image and Imagemaker art history faculty members. In honor of the fortieth anniversary of Women’s The Collection of Hobart and William Smith Colleges Studies at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, contains many works by women artists, only a few this exhibition shows a selection of artworks by of which are included in this exhibition. The earliest women depicting women from The Collections of the work in our collection by a woman is an 1896 Colleges. The selection of works played off the title etching, You Bleed from Many Wounds, O People, Double Vision: the vision of the women artists and the by Käthe Kollwitz (a gift of Elena Ciletti, Professor of vision of the women they depicted. This conjunction Art History). The latest work in the collection as of this of women artists and depicted women continues date is a 2012 woodcut, Glacial Moment, by Karen through the subtitle: woman as image (woman Kunc (a presentation of the Rochester Print Club). depicted as subject) and woman as imagemaker And we must also remember that often “anonymous (woman as artist). Ranging from a work by Mary was a woman.” Cassatt from the early twentieth century to one by Kara Walker from the early twenty-first century, we I want to take this opportunity to dedicate this see depictions of mothers and children, mythological exhibition and its catalog to the many women and figures, political criticism, abstract figures, and men who have fostered art and feminism for over portraits, ranging in styles from Impressionism to forty years at Hobart and William Smith Colleges New Realism and beyond. -

NEA-Annual-Report-1992.Pdf

N A N A L E ENT S NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR~THE ARTS 1992, ANNUAL REPORT NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR!y’THE ARTS The Federal agency that supports the Dear Mr. President: visual, literary and pe~orming arts to I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report benefit all A mericans of the National Endowment for the Arts for the fiscal year ended September 30, 1992. Respectfully, Arts in Education Challenge &Advancement Dance Aria M. Steele Design Arts Acting Senior Deputy Chairman Expansion Arts Folk Arts International Literature The President Local Arts Agencies The White House Media Arts Washington, D.C. Museum Music April 1993 Opera-Musical Theater Presenting & Commissioning State & Regional Theater Visual Arts The Nancy Hanks Center 1100 Pennsylvania Ave. NW Washington. DC 20506 202/682-5400 6 The Arts Endowment in Brief The National Council on the Arts PROGRAMS 14 Dance 32 Design Arts 44 Expansion Arts 68 Folk Arts 82 Literature 96 Media Arts II2. Museum I46 Music I94 Opera-Musical Theater ZlO Presenting & Commissioning Theater zSZ Visual Arts ~en~ PUBLIC PARTNERSHIP z96 Arts in Education 308 Local Arts Agencies State & Regional 3z4 Underserved Communities Set-Aside POLICY, PLANNING, RESEARCH & BUDGET 338 International 346 Arts Administration Fallows 348 Research 35o Special Constituencies OVERVIEW PANELS AND FINANCIAL SUMMARIES 354 1992 Overview Panels 360 Financial Summary 36I Histos~f Authorizations and 366~redi~ At the "Parabolic Bench" outside a South Bronx school, a child discovers aspects of sound -- for instance, that it can be stopped with the wave of a hand. Sonic architects Bill & Mary Buchen designed this "Sound Playground" with help from the Design Arts Program in the form of one of the 4,141 grants that the Arts Endowment awarded in FY 1992. -

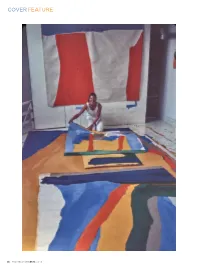

Coverfeature

COVER FEATURE 38 PROVINCETOWN ARTS 2018 Helen Frankenthaler In the pantheon of revered artists that constitutes the essential canon of Provincetown’s unique contribution to art history in America, the name Helen Frank enthaler (1928–2011) feels more distant, locally, than it deserves to be. Our focus on Frankenthaler in this issue explores the artist’s continuing inspiration for contemporary artists: Angela Dufresne’s passionate examination-by-alert-eye of Frankenthaler’s painting Holocaust, about which she spoke spontaneously into Jennifer Liese’s tape recorder while facing the work in situ at the Art Museum of the Rhode Island School of Design; Bonnie Clearwater’s account of her experience working with Frankenthaler to select a survey exhibition of works on paper for the Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami, Florida; and Mira Schor’s interpre- tation of the political, sexual, and competitive issues that Frankenthaler faced as a woman navigating the male-dominated world of the Abstract Expressionists. Finally, we show the ongoing influence of the artist’s work in a profile on Jeannie Motherwell, Frankenthaler’s stepdaughter and Robert Motherwell’s daughter, in whose work the family and artistic legacy continues. Abstract Climates: Helen Frankenthaler in Provincetown, the exhibition on view at the Provincetown Art Asso- ciation and Museum from July 6 through September 2, is devoted to works done by Frankenthaler during more than a decade of summers she spent living and working in Provincetown after her marriage to Robert Motherwell in 1958. Lise Motherwell, a stepdaughter of the artist and President of PAAM, curated the show with Elizabeth Smith, Executive Director of the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation in New York. -

Women Artists Utah Museum of Fine Arts • Lesson Plans for Educators October 28, 1998 Table of Contents

Women Artists Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Lesson Plans for Educators October 28, 1998 Table of Contents Page Contents 3 Image List 5 Woman Holding a Child with an Apple in its Hand,, Angelica Kauffmann 6 Lesson Plan for Untitled Written by Bernadette Brown 7 Princess Eudocia Ivanovna Galitzine as Flora, Marie Louise Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun 8 Lesson Plan for Flora Written by Melissa Nickerson 10 Jeanette Wearing a Bonnet, Mary Cassatt 12 Lesson Plan for Jeanette Wearing a Bonnet Written by Zelda B. McAllister 14 Sturm (Riot), Käthe Kollwitz 15 Lesson Plan for Sturm Written by Susan Price 17 Illustration for "Le mois de la chevre," Marie Laurencin 18 Lesson Plan for Illustration for "Le mois de la chevre" Written by Bernadette Brown 19 Illustration for Juste Present, Sonia Delaunay 20 Lesson Plan for Illustration for Juste Present Written by Melissa Nickerson 22 Gunlock, Utah, Dorothea Lange 23 Lesson Plan for Gunlock, Utah Written by Louise Nickelson 28 Newsstand, Berenice Abbott 29 Lesson Plan for Newsstand Written by Louise Nickelson 33 Gold Stone, Lee Krasner 34 Lesson Plan for Gold Stone Written by Melissa Nickerson 36 I’m Harriet Tubman, I Helped Hundreds to Freedom, Elizabeth Catlett 38 Lesson Plan for I’m Harriet Tubman Written by Louise Nickelson Evening for Educators is funded in part by the StateWide Art Partnership 1 Women Artists Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Lesson Plans for Educators October 28, 1998 Table of Contents (continued) Page Contents 46 Untitled, Helen Frankenthaler 48 Lesson Plan for Untitled Written by Virginia Catherall 51 Fourth of July Still Life, Audrey Flack 53 Lesson Plan for Fourth of July Still Life Written by Susan Price 55 Bibliography 2 Women Artists Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Lesson Plans for Educators October 28, 1998 Image List 1. -

The Studio Museum in Harlem Magazine Summer/Fall 2012 Studio Magazine Board of Trustees This Issue of Studio Is Underwritten, Editor-In-Chief Raymond J

The Studio Museum in Harlem Magazine Summer/Fall 2012 Studio Magazine Board Of Trustees This issue of Studio is underwritten, Editor-in-Chief Raymond J. McGuire, Chairman in part, with support from Bloomberg Elizabeth Gwinn Carol Sutton Lewis, Vice-Chair Creative Director Rodney M. Miller, Treasurer The Studio Museum in Harlem is supported, Thelma Golden in part, with public funds provided by Teri Trotter, Secretary Managing Editor the following government agencies and elected representatives: Dominic Hackley Jacqueline L. Bradley Valentino D. Carlotti Contributing Editors The New York City Department of Kathryn C. Chenault Lauren Haynes, Thomas J. Lax, Cultural A"airs; New York State Council Joan Davidson Naima J. Keith on the Arts, a state agency; National Gordon J. Davis Endowment for the Arts; Assemblyman Copy Editor Reginald E. Davis Keith L. T. Wright, 70th A.D. ; The City Samir Patel Susan Fales-Hill of New York; Council Member Inez E. Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Dickens, 9th Council District, Speaker Design Sandra Grymes Christine Quinn and the New York City Pentagram Joyce K. Haupt Council; and Manhattan Borough Printing Arthur J. Humphrey, Jr. President Scott M. Stringer. Finlay Printing George L. Knox !inlay.com Nancy L. Lane Dr. Michael L. Lomax The Studio Museum in Harlem is deeply Original Design Concept Tracy Maitland grateful to the following institutional 2X4, Inc. Dr. Amelia Ogunlesi donors for their leadership support: Corine Pettey Studio is published two times a year Bloomberg Philanthropies Ann Tenenbaum by The Studio Museum in Harlem, Doris Duke Charitable Foundation John T. Thompson 144 W. 125th St., New York, NY 10027. -

Catalog 221: Women BETWEEN the COVERS RARE BOOKS CATALOG 221: WOMEN

BETWEEN THE COVERS RARE BOOKS CATALOG 221: WOMEN BETWEEN THE COVERS RARE BOOKS CATALOG 221: WOMEN 112 Nicholson Rd. Terms of Sale: Images are not to scale. Dimensions of items, including artwork, are given width Gloucester City, NJ 08030 first. All items are returnable within 10 days if returned in the same condition as sent. Orders may be reserved by telephone, fax, or email. All items subject to prior sale. Payment should accompany phone: (856) 456-8008 order if you are unknown to us. Customers known to us will be invoiced with payment due in 30 fax: (856) 456-1260 days. Payment schedule may be adjusted for larger purchases. Institutions will be billed to meet their [email protected] requirements. We accept checks, Visa, Mastercard, American Express, Discover, and PayPal. betweenthecovers.com Gift certificates available. Domestic orders from this catalog will be shipped gratis for orders of $200 or more via UPS Ground or USPS Priority Mail; expedited and overseas orders will be sent at cost. All items insured. NJ residents will be charged sales tax. Member ABAA, ILAB. Cover image taken from item 60. Independent Online © 2018 Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc. Booksellers Association 1 (African-American) Verta MAE Thursdays and Every Other Sunday Off: A Domestic Rap Garden City: Doubleday 1972 $200 First edition. Fine in fine dustwrapper. Freeform essays and reflections about black domestic servants by the author of Vibration Cooking, or The Travel Notes of a Geechee Girl. Considering it was issued by a mainstream publisher, a surprisingly uncommon title. [BTC#418156] 2 (African-American) Constance H. -

For Immediate Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE LANDMARK SHOW "TO BE A LADY" BRINGS SUPERSTAR ARTISTS FROM AROUND THE WORLD TO SINGAPORE Exhibition dates: October 23, 2013–January 5, 2014 Opening cocktail reception: Wednesday, October 23, 6–9 pm Curated by Jason Andrew and organized by Sundaram Tagore Gallery in collaboration with Norte Maar Left: Helen Frankenthaler, Race Point, 1969, oil on canvas, 54.5 x 19 inches; private collection, courtesy Norte Maar, photo: Kris Graves Right: Louise Nevelson, Night Flower One, 1958, wood painted black, 36.25 x 24.75 x 3.75 inches; © 2013 Estate of Louise Nevelson/Artists Rights Society (ARS), courtesy Pace Gallery, New York Singapore, September 21, 2013—Sundaram Tagore Singapore is pleased to announce the landmark exhibition To Be a Lady: An International Celebration of Women in the Arts. Curated by Jason Andrew, the exhibition brings together an international selection of historic, mid-career, and emerging women artists born over the last century. Striking artworks by celebrated masters including Shirley Goldfarb, Louise Nevelson, Alice Neel and Helen Frankenthaler are juxtaposed with international stars such as Ghada Amer, Zhang Hui, Shirin Neshat and Yin Xiuzhen, setting the stage for a global exhibition designed to challenge and reshape the meaning of the word “lady.” (continued) For much of the last hundred years, women have been at the forefront of social and political reform worldwide. Whether Western suffragettes or activists in the Arab Spring, women have played and continue to play pivotal roles in bringing about revolutionary change. Their art and activism pushes beyond ideological lines, re-shaping and redefining the world we live in. -

Education Department

EDUCATION AND VISITOR SERVICES DEPARTMENT FY12 Annual Report 9/18/12 | 2 JULY 2011 – JUNE 2012 PROGRAMS AT A GLANCE Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………………………………….......4 Annual Museum Attendance: 96,298 Education Program Attendance: 34,765 (36.1% of total attendance) Strategic Plan Scorecard Key Success Drivers and Indicators FY12 Highlights Public Programs / Attendance: 8,930………………………………………………………………………………………6 Lectures: 8 programs / Attendance: 1,007 (per program average: 126) Gallery Talks: 14 programs / Attendance: 461 (per program average: 33) Collection Focused Talks: 6 programs / Attendance: 72 (per program average: 12) Sunday Serenades: 3 programs / Attendance: 447 (per program average: 149) Art After Hours: First Thursdays: 10 programs / Attendance: 8,428 (per program average: 843) Drawing in the Galleries: Still Life Studies / Students: 7 Annual Meeting Nook Farm Book Talks: Uncle Tom’s Cabin / Attendance: 45 Adult Tours / Attendance: 6,743 Family Programs / Attendance: 6,036………………………………………………………………………………………9 Second Saturdays for Families: 10 programs / Attendance: 6,092 (per program average: 609) Family Tours / Attendance: 663 Community Programs / Attendance: 3,496………………………………………………………………………………10 Community Days: 3 programs / Attendance: 2,458 (per program average: 819) Artist Residencies: 2 programs / 2 community partners and 26 youth served Summer Art Studio / Attendance: 350 First Night / Attendance: 971 Charter Oak Cultural Center, Youth Arts Institute After-School collaboration: 3 tours / Attendance: