Executive Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

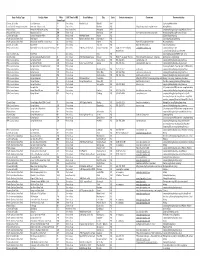

Sorted by Facility Type.Xlsm

Basic Facility Type Facility Name Miles AVG Time In HRS Street Address City State Contact information Comments Known activities (from Cary) Comercial Facility Ace Adventures 267 5 hrs or less Minden Road Oak Hill WV Kayaking/White Water East Coast Greenway Association American Tobacco Trail 25 1 hr or less Durham NC http://triangletrails.org/american- Biking/hiking Military Bases Annapolis Military Academy 410 more than 6 hrs Annapolis MD camping/hiking/backpacking/Military History National Park Service Appalachian Trail 200 5 hrs or less Damascus VA Various trail and entry/exit points Backpacking/Hiking/Mountain Biking Comercial Facility Aurora Phosphate Mine 150 4 hrs or less 400 Main Street Aurora NC SCUBA/Fossil Hunting North Carolina State Park Bear Island 142 3 hrs or less Hammocks Beach Road Swannsboro NC Canoeing/Kayaking/fishing North Carolina State Park Beaverdam State Recreation Area 31 1 hr or less Butner NC Part of Falls Lake State Park Mountain Biking Comercial Facility Black River 90 2 hrs or less Teachey NC Black River Canoeing Canoeing/Kayaking BSA Council camps Blue Ridge Scout Reservation-Powhatan 196 4 hrs or less 2600 Max Creek Road Hiwassee (24347) VA (540) 777-7963 (Shirley [email protected] camping/hiking/copes Neiderhiser) course/climbing/biking/archery/BB City / County Parks Bond Park 5 1 hr or less Cary NC Canoeing/Kayaking/COPE/High ropes Church Camp Camp Agape (Lutheran Church) 45 1 hr or less 1369 Tyler Dewar Lane Duncan NC Randy Youngquist-Thurow Must call well in advance to schedule Archery/canoeing/hiking/ -

Visitors Guide

LUMBERTON NORTHNORTH CAROLINACAROLINA When you stop here, you’re halfway there! Exits 17-22 New York 626 Richmond 240 74 ★ Charleston 166 Orlando 501 Miami 710 VISITORS GUIDE 3431 LACKEY STREET, LUMBERTON, NC 28360 1-800-359-6971 • (910) 739-9999 • [email protected] www.lumberton-nc.com Welcome To Lumberton, North Carolina Location, Location, Location! Ideally located on Interstate 95, Lumberton is known as the halfway point between New York and Florida. Just South of Lumberton’s city limits at Exit 13, I-74, another major interstate, intersects I-95. Our hotels and restaurants, conveniently located along the I- 95 corridor, make traveling easy for the visitors. Take any of our four exits – 17, 19, 20, or 22 – and you will have your choice of over 1500 hotel rooms and suites. NC BBQ, local flavor, seafood, fine dining, Chinese, Mexican, Japanese, and fast food are all available for your enjoyment. Spend the night with us and wake up to history, culture, and fun. Hike and bike on the Riverwalk near Historic Downtown as you enjoy the beauty of the Lumber River, listed as a National Wild and Scenic River and voted one of North Carolina’s Top Ten Natural Wonders. The natural setting of Lumberton contributes to its charm almost as much as the people. Lumberton was designated the first Certified Retirement Community in NC. We offer all the assets that attract retirees – moderate climate, affordable housing, excellent medical care, natural beauty, entertainment, historic and cultural attractions, recreation, and nearness to the beach, mountains and great golf. When you stop here, you’re halfway there! CONTENTS Exit 13 ................................................................ -

Nc State Parks

GUIDE TO NC STATE PARKS North Carolina’s first state park, Mount Mitchell, offers the same spectacular views today as it did in 1916. 42 OUR STATE GUIDE to the GREAT OUTDOORS North Carolina’s state parks are packed with opportunities: for adventure and leisure, recreation and education. From our highest peaks to our most pristine shorelines, there’s a park for everyone, right here at home. ACTIVITIES & AMENITIES CAMPING CABINS MILES 5 THAN MORE HIKING, RIDING HORSEBACK BICYCLING CLIMBING ROCK FISHING SWIMMING SHELTER PICNIC CENTER VISITOR SITE HISTORIC CAROLINA BEACH DISMAL SWAMP STATE PARK CHIMNEY ROCK STATE PARK SOUTH MILLS // Once a site of • • • CAROLINA BEACH // This coastal park is extensive logging, this now-protected CROWDERSMOUNTAIN • • • • • • home to the Venus flytrap, a carnivorous land has rebounded. Sixteen miles ELK KNOB plant unique to the wetlands of the of trails lead visitors around this • • Carolinas. Located along the Cape hauntingly beautiful landscape, and a GORGES • • • • • • Fear River, this secluded area is no less 2,000-foot boardwalk ventures into GRANDFATHERMOUNTAIN • • dynamic than the nearby Atlantic. the Great Dismal Swamp itself. HANGING ROCK (910) 458-8206 (252) 771-6593 • • • • • • • • • • • ncparks.gov/carolina-beach-state-park ncparks.gov/dismal-swamp-state-park LAKE JAMES • • • • • LAKE NORMAN • • • • • • • CARVERS CREEK STATE PARK ELK KNOB STATE PARK MORROW MOUNTAIN • • • • • • • • • WESTERN SPRING LAKE // A historic Rockefeller TODD // Elk Knob is the only park MOUNT JEFFERSON • family vacation home is set among the in the state that offers cross- MOUNT MITCHELL longleaf pines of this park, whose scenic country skiing during the winter. • • • • landscape spans more than 4,000 acres, Dramatic elevation changes create NEW RIVER • • • • • rich with natural and historical beauty. -

Lumberton Recovery Plan

2018 LUMBERTON RECOVERY PLAN LUMBERTON RECOVERY PLAN October 2018 Prepared by: Hurricane Matthew Disaster Recovery and Resilience Initiative Coastal Resilience Center The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Lumberton, North Carolina Hurricane Matthew Recovery Plan October 2018 Prepared by: The Hurricane Matthew Disaster Recovery and Resilience Initiative, a collaborative program involving the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and North Carolina State University. Funding provided by the North Carolina Division of Emergency Management and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Policy Collaboratory. LUMBERTON, NORTH CAROLINA RECOVERY PLAN ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We are grateful to the following agencies and individuals who contributed their time and expertise to the development of this recovery plan: • Wayne Horne City Manager • Brandon Love Director of Planning and Neighborhood Services • Holt Moore City Attorney • Tim Taylor Director of Recreation • Robert P. Armstrong Public Works Director • Teresa Johnson Community Development Administrator • Linda Maynor-Oxendine Public Services Director • Michael McNeill Chief of Police • Paul Ivey Fire Chief • Bill French Director of Emergency Services • Alisha Thompson Director of Finance • Connie Russ Downtown Coordinator • Mary Schultz Executive Director, Shining Stars Preschool • Mattie Caulder Assistant Director, Robeson County Emergency Management • Stephanie Chavis Executive Director, Robeson County Emergency Management • Channing Jones Director, Robeson County Economic -

Bob White Lodge Where to Go Camping Guide Here

Path To A Great Camping Trip Bob White Lodge BSA Camping Guide 2012 Dear Scouts and Scoutmasters, Since the Bob White Lodge’s founding in 1936, we have continuously strived to fulfill the Order of the Arrow’s purpose to promote camping, responsible outdoor adventure, and environmental stewardship as essential components of every Scout’s experience, in the Unit, year-round, and in Summer Camp. We believe the annual publication of a Where To Go Camping Guide is a useful planning tool for all Scouting Units to help them provide that quality outdoor experience. We hope you enjoy the new features we’ve introduced for 2012: · A user-friendly color code system and icons to identify camping locations across the States and within regions of each State. · Updated site descriptions, information, and photographs. · New listings for favorite hiking trails and other camping sites, including web sites addresses to obtain greater information. · Details about Knox Scout Reservation, including off-season use of this wonderful Council Camp. I trust you will let us know if you have suggestions or feedback for next year’s edition. The Guide is on the Georgia-Carolina Council web site www.gacacouncil.org, the Bob White Lodge website www.bobwhitelodge.org, and a copy will be available for review at the council office. Yours in Service, Brandt Boudreaux Lodge Chief Bob White Lodge # 87 Color Legend Camping in Georgia Camping in South Carolina Camping in North Carolina High Adventure Bases Hiking Trails Camp Knox Scout Reservation BSA Policies and Camping This Where to Go Camping Guide has excluded parks or other locations that are for recreational vehicles (RVs) only or camping for six or fewer people as of the publication date. -

GENERAL ASSEMBLY of NORTH CAROLINA SESSION 2003 S D SENATE DRS15241-Riz-9 (4/2)

GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF NORTH CAROLINA SESSION 2003 S D SENATE DRS15241-RIz-9 (4/2) Short Title: State Nat. & Hist. Preserve Removals. (Public) Sponsors: Senator Horton. Referred to: 1 A BILL TO BE ENTITLED 2 AN ACT TO REMOVE CERTAIN LANDS FROM THE STATE NATURE AND 3 HISTORIC PRESERVE AND TO DELETE A PORTION OF A PARK FROM 4 THE STATE PARKS SYSTEM, AS RECOMMENDED BY THE 5 ENVIRONMENTAL REVIEW COMMISSION. 6 Whereas, Section 5 of Article XIV of the Constitution of North Carolina 7 authorizes the dedication of State and local government properties as part of the State 8 Nature and Historic Preserve upon acceptance by a law enacted by a three-fifths vote of 9 the members of each house of the General Assembly and provides for removal of 10 properties from the State Nature and Historic Preserve by a law enacted by a three-fifths 11 vote of the members of each house of the General Assembly; and 12 Whereas, the General Assembly enacted the State Nature and Historic 13 Preserve Dedication Act, Chapter 443 of the 1973 Session Laws, to prescribe the 14 conditions and procedures under which properties may be specifically dedicated for the 15 purposes set out in Section 5 of Article XIV of the Constitution of North Carolina; and 16 Whereas, G.S. 113-44.14 provides for additions to, and deletions from, the 17 State Parks System upon authorization by the General Assembly; Now, therefore, 18 The General Assembly of North Carolina enacts: 19 SECTION 1. G.S. 143-260.10 reads as rewritten: 20 "§ 143-260.10. -

UMBER RIVER (A)(Ii) Wild & Scenic River Study Report

UMBER RIVER (a)(ii) Wild & Scenic River Study Report United States Department of the Interior January 1998 National Park Service Southeast Region United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Southeast Regional Office Atlanta Federal Center IN REPLY REFER TO: 1924 Building 100 Alabama St., S.W. Atlanta, Georgia 30303 April 17, 1998 Dear Interested Party: The Nationai.Park Se:rvice is extending the public comment period for the draft Lumber River 2(a)(ii) Wild & Scenic River Study Report and Environmental Assessment through June 12, 1998. If you have any questions regarding this extension or the draft report and environmental assessment, please contact Mary Rountree at 404-562-3175. Sincerely, ~;{/~ Mary K. Rountree Landscape Architect Executive Summary On April15, 1996, North Carolina Governor James Hunt petitioned the Secretary of the United States Deparhnent of the Interior to designate the Lumber River in North Carolina a national wild and scenic river. The National Park Service is conducting the assessment of North Carolina's application according to Deparhnent of the Interior guidelines. The National Park Service is conducting the environmental analysis required by the National Environmental Policy Act. This document represents the draft of both those analyses and is being released in order to solicit public and agency comment. The state of North Carolina and the Lumber River fully met three of four requirements for designation as a National Wild and Scenic River. The requirements that were fully met include: 1) designation of the river into a State wild and scenic river system; 2) management of the river by a political subdivision of the State; and 3) possession of eligibility criteria common to all national wild and scenic rivers, that is, the river is free-flowing and possesses one or more outstandingly remarkable values. -

Sorted by City.Xlsm

Basic Facility Type Facility Name Miles AVG Time In HRS Street Address City State Contact information Comments Known activities (from Cary) North Carolina State Park Morrow Mountain State Park 90 2 hrs or less Albemarle NC www.dpr.ncparks.com camping/hiking/backpacking/ Military Bases Annapolis Military Academy 410 more than 6 hrs Annapolis MD camping/hiking/backpacking/Military History Comercial Facility Jordan Lake Christmas Tree Farm 19 1 hr or less 2170 MARTHA'S CHAPEL Apex NC 919-362-6300 http://www.jordanlakechristmas.com/ Pistol shooting/Venture Adventure ROAD North Carolina State Park Jordan Lake - Crosswinds 10 1 hr or less Apex NC http://www.ncparks.gov/Visit/parks/jord/ camping/hiking/backpacking/board directions.php sailing/boating/Water Skiing North Carolina State Park Jordan Lake - New Hope Overlook 10 1 hr or less Apex NC http://www.ncparks.gov/Visit/parks/jord/ camping/hiking/backpacking/Primitive camping directions.php North Carolina State Park Jordan Lake - Parkers Creek 10 1 hr or less Apex NC http://www.ncparks.gov/Visit/parks/jord/ camping/hiking/backpacking/boating/Water directions.php Skiing North Carolina State Park Jordan Lake - Poplar Point 10 1 hr or less Apex NC http://www.ncparks.gov/Visit/parks/jord/ camping/hiking/backpacking/boating/Water directions.php Skiing North Carolina State Park Jordan Lake - Vista Point 10 1 hr or less Apex NC http://www.ncparks.gov/Visit/parks/jord/ camping/hiking/backpacking/boating/Water directions.php Skiing BSA Council camps Woodfield Scout Preservation 73 2 hrs or less 491 -

NC Wetlands Passport

OLINA — AR C H T R O N — N I A L P L A T S A O C — T N M O O M UN D TAINS—PIE www.ncwetlands.org NCwetlands.org is an outreach project of the North Carolina Division of Water Resources, with funding from the US Environmental Protection Agency. Passport created in 2018. We are excited that you are joining us on a North Carolina wetland journey! We hope this passport will help you find wetlands you’ve never seen before or help you reconnect with wetlands you may have forgotten. This passport will unlock the door to your future wetland adventures in North Carolina - in wetlands right next door or wetlands on the opposite side of the state. Let your North Carolina wetland adventure begin! What is in the passport: Be safe: This passport lists and maps Have fun on your wetland over 220 publicly accessible adventures, but also be safe. When wetlands across North Carolina. possible, contact the location to Sites are listed alphabetically by confirm hours of operation. While ecoregion (Mountain, Piedmont, these wetlands are publicly and Coastal Plain) with address accessible, there may be guidelines information provided. Wetland and restrictions at some of the sites. sites are numbered in the order Be sure to follow all guidelines and listed and shown on a centerfold signage at a wetland site. map (pages 6-7). Many of these wetlands are located To find a wetland site: on state game lands which are open Use the centerfold map to find a to hunting and gates may be closed site number in an area you want to during parts of the year. -

North Carolina Outdoor Recreation Plan 2020 - 2025

NORTH CAROLINA OUTDOOR RECREATION PLAN 2020 - 2025 Division of Parks and Recreation NC Department of Natural and Cultural Resources May 2020 Introduction North Carolina has been blessed with a rich and varied tapestry of lands and waters. The landscape stretches from the Tidewater’s ocean beaches, sounds and marshes westward through flat Coastal Plain swamp forests to the rolling Piedmont and on to ancient and hauntingly beautiful mountains, well-known and loved not just by North Carolinians, but by millions of Americans nationwide. Traversing and connecting this landscape are picturesque rivers and streams. These lands and waters provide not only breathtaking scenery and magnificent settings for outdoor recreation, but also serve to support a rich diversity of plant and animal life. North Carolina is indeed “Naturally Wonderful”. Executive Summary Since passage of the federal Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) Act of 1965, preparation of a Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) has been required for states to be eligible for LWCF acquisition and development assistance. Past SCORPs and this edition have provided a coordinated framework addressing the problems, needs, and opportunities related to the need for improved public outdoor recreation. The N.C. Division of Parks and Recreation, the state agency with authority to represent and act for the state for purposes of the LWCF Act, prepared this plan. LWCF funds have provided over $11 million for projects in North Carolina during the past five years, an average of $2.3 million annually. Since 1965, more than $90 million of LWCF assistance has been provided for more than 1000 projects. -

Scenic Byways

n c s c e n i c b y w a y s a h c rol rt in o a n fourth edition s c s en ay ic byw North Carolina Department of Transportation Table of ConTenTs Click on Byway. Introduction Legend NCDOT Programs Rules of the Road Cultural Resources Blue Ridge Parkway Scenic Byways State Map MOuntains Waterfall Byway Nantahala Byway Cherohala Skyway Indian Lakes Scenic Byway Whitewater Way Forest Heritage Scenic Byway appalachian Medley French Broad Overview Historic Flat Rock Scenic Byway Drovers Road Black Mountain Rag Pacolet River Byway South Mountain Scenery Mission Crossing Little Parkway New River Valley Byway I-26 Scenic Highway u.S. 421 Scenic Byway Pisgah Loop Scenic Byway upper Yadkin Way Yadkin Valley Scenic Byway Smoky Mountain Scenic Byway Mt. Mitchell Scenic Drive PIedmont Hanging Rock Scenic Byway Colonial Heritage Byway Football Road Crowders Mountain Drive Mill Bridge Scenic Byway 2 BACK TO TABLE OF CONTENTS BACK TO BYWAYS MAP Table of ConTenTs uwharrie Scenic Road Rolling Kansas Byway Pee Dee Valley Drive Grassy Island Crossing Sandhills Scenic Drive Birkhead Wilderness Route Flint Hill Ramble Indian Heritage Trail Pottery Road Devil’s Stompin’ Ground Road North Durham Country Byway averasboro Battlefield Scenic Byway Clayton Bypass Scenic Byway Scots-Welsh Heritage Byway COastaL PLain Blue-Gray Scenic Byway Meteor Lakes Byway Green Swamp Byway Brunswick Town Road Cape Fear Historic Byway Lafayette’s Tour Tar Heel Trace edenton-Windsor Loop Perquimans Crossing Pamlico Scenic Byway alligator River Route Roanoke Voyages Corridor Outer Banks Scenic Byway State Parks & Recreation areas Historic Sites For More Information Bibliography 3 BACK TO TABLE OF CONTENTS BACK TO BYWAYS MAP inTroduction The N.C. -

NC DIVISION of PARKS and RECREATION July 2018

The NC DIVISION OF PARKS AND RECREATION July 2018 www.ncparks.gov South Mountains Celebrates New Acreage, Access, Accolades South Mountains State Park staf welcomed 50 guests and local elementary school students to the park April 20 to celebrate recent successes. Students from Hildebran Elementary School joined rangers in a ribbon cutting to open the newly re-routed Chestnut Knob Trail, which had been closed in 2016 due to wildfre damage. Friends, volunteers, visitors and park staf came together to celebrate the park, which was named the 2017 Park of the Year—an award given each January based on a park’s accomplishments the year prior. Representatives from The Conservation Fund and Foothills Land Conservancy of North Carolina joined the gathering to celebrate the partnership with state parks that added over 1,000 new acres of land to the park last year, bringing the size of South Mountains State Park to over 20,000 acres—by far the largest in our state parks system. South Mountains State Park staf Umstead Swaps Land; Plans Safer Crabtree Entrance In a recent agreement between the Division of Parks and Recreation and afliates of Anderson Automotive Group, Inc., parcels of land near the Crabtree Creek entrance of William B. Umstead State Park will be exchanged. The exchange will alleviate long- standing trafc and safety issues at the existing park entrance. More than 825,000 people used the Crabtree entrance to access Umstead State Park last year. The property acquisition will allow the park to re-route the park entrance to a trafc signal at Glenwood Avenue and Triangle Drive.