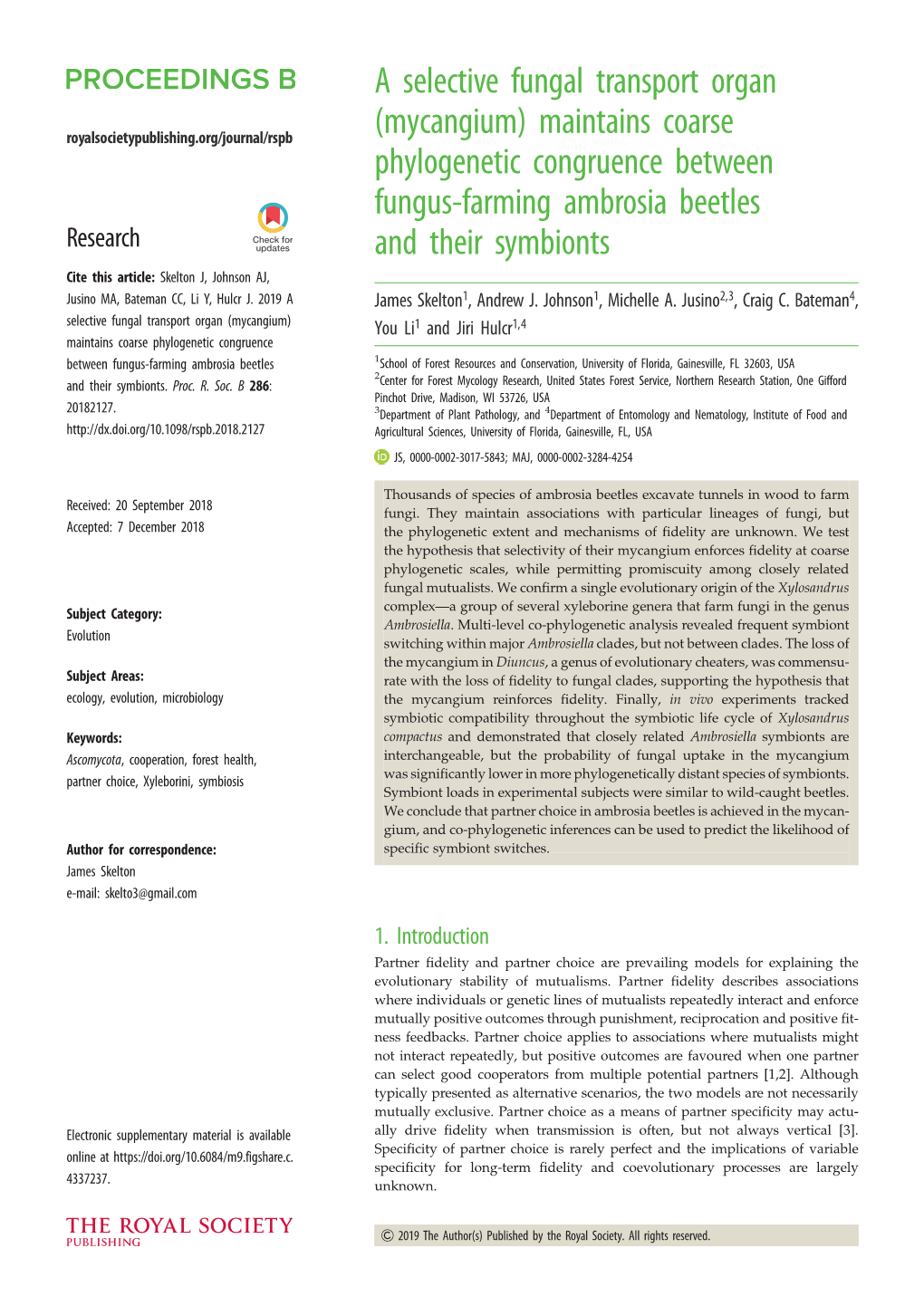

(Mycangium) Maintains Coarse Phylogenetic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bretziella, a New Genus to Accommodate the Oak Wilt Fungus

A peer-reviewed open-access journal MycoKeys 27: 1–19 (2017)Bretziella, a new genus to accommodate the oak wilt fungus... 1 doi: 10.3897/mycokeys.27.20657 RESEARCH ARTICLE MycoKeys http://mycokeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Bretziella, a new genus to accommodate the oak wilt fungus, Ceratocystis fagacearum (Microascales, Ascomycota) Z. Wilhelm de Beer1, Seonju Marincowitz1, Tuan A. Duong2, Michael J. Wingfield1 1 Department of Microbiology and Plant Pathology, Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute (FABI), University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0002, South Africa 2 Department of Genetics, Forestry and Agricultural Bio- technology Institute (FABI), University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0002, South Africa Corresponding author: Z. Wilhelm de Beer ([email protected]) Academic editor: T. Lumbsch | Received 28 August 2017 | Accepted 6 October 2017 | Published 20 October 2017 Citation: de Beer ZW, Marincowitz S, Duong TA, Wingfield MJ (2017) Bretziella, a new genus to accommodate the oak wilt fungus, Ceratocystis fagacearum (Microascales, Ascomycota). MycoKeys 27: 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3897/ mycokeys.27.20657 Abstract Recent reclassification of the Ceratocystidaceae (Microascales) based on multi-gene phylogenetic infer- ence has shown that the oak wilt fungus Ceratocystis fagacearum does not reside in any of the four genera in which it has previously been treated. In this study, we resolve typification problems for the fungus, confirm the synonymy ofChalara quercina (the first name applied to the fungus) andEndoconidiophora fagacearum (the name applied when the sexual state was discovered). Furthermore, the generic place- ment of the species was determined based on DNA sequences from authenticated isolates. The original specimens studied in both protologues and living isolates from the same host trees and geographical area were examined and shown to represent the same species. -

Saprophytic and Pathogenic Fungi in the Ceratocystidaceae Differ in Their Ability to Metabolize Plant-Derived Sucrose M

Van der Nest et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology (2015) 15:273 DOI 10.1186/s12862-015-0550-7 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Saprophytic and pathogenic fungi in the Ceratocystidaceae differ in their ability to metabolize plant-derived sucrose M. A. Van der Nest1*, E. T. Steenkamp2, A. R. McTaggart2, C. Trollip1, T. Godlonton1, E. Sauerman1, D. Roodt1, K. Naidoo1, M. P. A. Coetzee1, P. M. Wilken1, M. J. Wingfield2 and B. D. Wingfield1 Abstract Background: Proteins in the Glycoside Hydrolase family 32 (GH32) are carbohydrate-active enzymes known as invertases that hydrolyse the glycosidic bonds of complex saccharides. Fungi rely on these enzymes to gain access to and utilize plant-derived sucrose. In fungi, GH32 invertase genes are found in higher copy numbers in the genomes of pathogens when compared to closely related saprophytes, suggesting an association between invertases and ecological strategy. The aim of this study was to investigate the distribution and evolution of GH32 invertases in the Ceratocystidaceae using a comparative genomics approach. This fungal family provides an interesting model to study the evolution of these genes, because it includes economically important pathogenic species such as Ceratocystis fimbriata, C. manginecans and C. albifundus, as well as saprophytic species such as Huntiella moniliformis, H. omanensis and H. savannae. Results: The publicly available Ceratocystidaceae genome sequences, as well as the H. savannae genome sequenced here, allowed for the identification of novel GH32-like sequences. The de novo assembly of the H. savannae draft genome consisted of 28.54 megabases that coded for 7 687 putative genes of which one represented a GH32 family member. -

Low Intraspecific Genetic Diversity Indicates Asexuality and Vertical

Fungal Ecology 32 (2018) 57e64 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Fungal Ecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/funeco Low intraspecific genetic diversity indicates asexuality and vertical transmission in the fungal cultivars of ambrosia beetles * ** L.J.J. van de Peppel a, , D.K. Aanen a, P.H.W. Biedermann b, c, a Laboratory of Genetics Wageningen University, 6700 AH Wageningen, The Netherlands b Max-Planck-Institut for Chemical Ecology, Department of Biochemistry, Hans-Knoll-Strasse€ 8, 07745 Jena, Germany c Research Group Insect-Fungus Symbiosis, Department of Animal Ecology and Tropical Biology, University of Wuerzburg, Biocenter, Am Hubland, 97074 Wuerzburg, Germany article info abstract Article history: Ambrosia beetles farm ascomycetous fungi in tunnels within wood. These ambrosia fungi are regarded Received 21 July 2016 asexual, although population genetic proof is missing. Here we explored the intraspecific genetic di- Received in revised form versity of Ambrosiella grosmanniae and Ambrosiella hartigii (Ascomycota: Microascales), the mutualists of 9 November 2017 the beetles Xylosandrus germanus and Anisandrus dispar. By sequencing five markers (ITS, LSU, TEF1a, Accepted 29 November 2017 RPB2, b-tubulin) from several fungal strains, we show that X. germanus cultivates the same two clones of Available online 29 December 2017 A. grosmanniae in the USA and in Europe, whereas A. dispar is associated with a single A. hartigii clone Corresponding Editor: Henrik Hjarvard de across Europe. This low genetic diversity is consistent with predominantly asexual vertical transmission Fine Licht of Ambrosiella cultivars between beetle generations. This clonal agriculture is a remarkable case of convergence with fungus-farming ants, given that both groups have a completely different ecology and Keywords: evolutionary history. -

Insect Ecology-An Ecosystem Approach

FM-P088772.qxd 1/24/06 11:11 AM Page xi PREFACE his second edition provides an updated and expanded synthesis of feedbacks and interactions between insects and their environment. A number of recent studies have T advanced understanding of feedbacks or provided useful examples of principles. Mo- lecular methods have provided new tools for addressing dispersal and interactions among organisms and have clarified mechanisms of feedback between insect effects on, and responses to, environmental changes. Recent studies of factors controlling energy and nutri- ent fluxes have advanced understanding and prediction of interactions among organisms and abiotic nutrient pools. The traditional focus of insect ecology has provided valuable examples of adaptation to environmental conditions and evolution of interactions with other organisms. By contrast, research at the ecosystem level in the last 3 decades has addressed the integral role of her- bivores and detritivores in shaping ecosystem conditions and contributing to energy and matter fluxes that influence global processes. This text is intended to provide a modern per- spective of insect ecology that integrates these two traditions to approach the study of insect adaptations from an ecosystem context. This integration substantially broadens the scope of insect ecology and contributes to prediction and resolution of the effects of current envi- ronmental changes as these affect and are affected by insects. This text demonstrates how evolutionary and ecosystem approaches complement each other, and is intended to stimulate further integration of these approaches in experiments that address insect roles in ecosystems. Both approaches are necessary to understand and predict the consequences of environmental changes, including anthropogenic changes, for insects and their contributions to ecosystem structure and processes (such as primary pro- ductivity, biogeochemical cycling, carbon flux, and community dynamics). -

Fungi-Insect Symbiosis Laboulbeniomycetes

Important Dates zDecember 6th – Last lecture. zDecember 12th – Study session at 2:30? Where? Fungi-Insect zDecember 13th – Final Exam: 12:00-2:00 Symbiosis Fungi-Insect Symbiosis Fungi-Insect Symbiosis zMany examples of fungi-insect zMany examples of fungi-insect symbiosis. symbiosis (continue). zCover the following examples zInsects that cultivate fungi: Laboulbeniomycetes – Class of Attine Ants Ascomycota. Mostly on insects. Septobasidium –Genus of Mound Building Termites Basidiomycota Ambrosia Beetles Laboulbeniomycetes Laboulbeniomycetes zAscocarps occur on very specific zVery poorly known example. localities in some species: zRelationship between fungi and insects unclear. One species parasitic? Species of this fungus probably occurs on all insects Fungus is a member of Ascomycota zRickia dendroiuli Only found on forelegs of millipedes 1 Rickia dendroiuli Rickia dendroiuli Mature ascocarp zLow magnification showing three ascocarps zHigh magnification showing two ascocarps, as seen through the microscope. left is mature Laboulbeniomycetes Laboulbeniomycetes zIn some species specific localities zVariations were based on mating habit misleading. For example: of insects involved. In some insects, “species A” may have ascocarps arising only on front, upper pair of legs of males However, “Species A” have ascocarps arising only on the back, lower pair of legs of females of same insect species. Peyritschiella protea Peyritschiella protea zAscocarps not zHigh magnification always in specific of ascocarps and localities. ascospores. ascocarps and ascospores 2 Stigmatomyces majewski Stigmatomyces majewskii zLow and high z Ascocarps occur magnification mostly on of ascocarps. segment. zNote one on wing. Laboulbenia cristata Laboulbenia cristata zAscocarps occur on zHigh magnification middle segment of ascocarp with legs. ascospores. SeptobasidiuSeptobasidiumm SeptobasidiuSeptobasidiumm zGenus of Basidiomycota that forms a zMore examples: symbiotic relationship with scale insects. -

Characterization of the Ergosterol Biosynthesis Pathway in Ceratocystidaceae

Journal of Fungi Article Characterization of the Ergosterol Biosynthesis Pathway in Ceratocystidaceae Mohammad Sayari 1,2,*, Magrieta A. van der Nest 1,3, Emma T. Steenkamp 1, Saleh Rahimlou 4 , Almuth Hammerbacher 1 and Brenda D. Wingfield 1 1 Department of Biochemistry, Genetics and Microbiology, Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute (FABI), University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0002, South Africa; [email protected] (M.A.v.d.N.); [email protected] (E.T.S.); [email protected] (A.H.); brenda.wingfi[email protected] (B.D.W.) 2 Department of Plant Science, University of Manitoba, 222 Agriculture Building, Winnipeg, MB R3T 2N2, Canada 3 Biotechnology Platform, Agricultural Research Council (ARC), Onderstepoort Campus, Pretoria 0110, South Africa 4 Department of Mycology and Microbiology, University of Tartu, 14A Ravila, 50411 Tartu, Estonia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Fax: +1-204-474-7528 Abstract: Terpenes represent the biggest group of natural compounds on earth. This large class of organic hydrocarbons is distributed among all cellular organisms, including fungi. The different classes of terpenes produced by fungi are mono, sesqui, di- and triterpenes, although triterpene ergosterol is the main sterol identified in cell membranes of these organisms. The availability of genomic data from members in the Ceratocystidaceae enabled the detection and characterization of the genes encoding the enzymes in the mevalonate and ergosterol biosynthetic pathways. Using Citation: Sayari, M.; van der Nest, a bioinformatics approach, fungal orthologs of sterol biosynthesis genes in nine different species M.A.; Steenkamp, E.T.; Rahimlou, S.; of the Ceratocystidaceae were identified. -

Ceratocystidaceae Exhibit High Levels of Recombination at the Mating-Type (MAT) Locus

Accepted Manuscript Ceratocystidaceae exhibit high levels of recombination at the mating-type (MAT) locus Melissa C. Simpson, Martin P.A. Coetzee, Magriet A. van der Nest, Michael J. Wingfield, Brenda D. Wingfield PII: S1878-6146(18)30293-9 DOI: 10.1016/j.funbio.2018.09.003 Reference: FUNBIO 959 To appear in: Fungal Biology Received Date: 10 November 2017 Revised Date: 11 July 2018 Accepted Date: 12 September 2018 Please cite this article as: Simpson, M.C., Coetzee, M.P.A., van der Nest, M.A., Wingfield, M.J., Wingfield, B.D., Ceratocystidaceae exhibit high levels of recombination at the mating-type (MAT) locus, Fungal Biology (2018), doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.funbio.2018.09.003. This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT 1 Title 2 Ceratocystidaceae exhibit high levels of recombination at the mating-type ( MAT ) locus 3 4 Authors 5 Melissa C. Simpson 6 [email protected] 7 Martin P.A. Coetzee 8 [email protected] 9 Magriet A. van der Nest 10 [email protected] 11 Michael J. Wingfield 12 [email protected] 13 Brenda D. -

Interactions Between Southern Pine Beetle, Mites, Microbes, and Trees Kier D

From Attack to Emergence: Interactions between Southern Pine Beetle, Mites, Microbes, and Trees Kier D. Klepzig1 and Richard W. Hofstetter2 9 1 Assistant Director-Research, USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station, Asheville, NC, 28804 2Assistant Professor, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ 86011-5018 Abstract Bark beetles are among the most ecologically and economically influential organisms in forest ecosystems worldwide. These important organisms are consistently associated in complex symbioses with fungi. Despite this, little is known of the net impacts of the fungi on their vectors, and mites are often completely overlooked. In this chapter, we will describe interactions involving the southern pine beetle (SPB), among the most economically damaging of North American forest insects. We examine SPB interactions with mites, fungi, and other microbes, following the natural temporal progression from beetle attack to offspring emergence from trees. Associations with fungi are universal within bark beetles. Many beetle species possess specialized structures, termed mycangia, for the transport of fungi. The SPB consistently carries three main Keywords fungi and numerous mites into the trees it attacks. One fungus, Ophiostoma minus, is carried phoretically on the SPB exoskeleton and by phoretic mites. actinomycetes symbiosis The mycangium of each female SPB may contain a pure culture of either Dendroctonus frontalis Ceratocystiopsis ranaculosus or Entomocorticium sp. A. The mycangial fungi Ceratocystiopsis are, by definition, transferred in a specific fashion. The SPB possesses two types Entomocorticiun of gland cells associated with the mycangium. The role of these cells and their mycangium products remains unknown. Preliminary studies have observed yeast-like fungal Ophiostoma minus, spores in the mycangium and several surrounding tubes that presumably carry secreted chemicals from gland cells (or bacteria) to the mycangium. -

Fungi of Raffaelea Genus (Ascomycota: Ophiostomatales) Associated to Platypus Cylindrus (Coleoptera: Platypodidae) in Portugal

FUNGI OF RAFFAELEA GENUS (ASCOMYCOTA: OPHiostomATALES) ASSOCIATED to PLATYPUS CYLINDRUS (COLEOPTERA: PLATYPODIDAE) IN PORTUGAL FUNGOS DO GÉNERO RAFFAELEA (ASCOMYCOTA: OPHiostomATALES) ASSOCIADOS A PLATYPUS CYLINDRUS (COLEOPTERA: PLATYPODIDAE) EM PORTUGAL MARIA LURDES INÁCIO1, JOANA HENRIQUES1, ARLINDO LIMA2, EDMUNDO SOUSA1 ABSTRACT Key-words: Ambrosia beetle, ambrosia fun- gi, cork oak, decline. In the study of the fungi associated to Platypus cylindrus, several fungi were isolated from the insect and its galleries in cork oak, RESUMO among which three species of Raffaelea. Mor- phological and cultural characteristics, sensitiv- No estudo dos fungos associados ao insec- ity to cycloheximide and genetic variability had to xilomicetófago Platypus cylindrus foram been evaluated in a set of isolates of this genus. isolados, a partir do insecto e das suas ga- On this basis R. ambrosiae and R. montetyi were lerias no sobreiro, diversos fungos, entre os identified and a third taxon segregated witch quais três espécies de Raffaelea. Avaliaram-se differs in morphological and molecular charac- características morfológicas e culturais, sensibi- teristics from the previous ones. In this work we lidade à ciclohexamida e variabilidade genética present and discuss the parameters that allow num conjunto de isolados do género. Foram the identification of specimens of the threetaxa . identificados R. ambrosiae e R. montetyi e The role that those ambrosia fungi can have in segregou-se um terceiro táxone que difere the cork oak decline is also discussed taking em características morfológicas e molecula- into account that Ophiostomatales fungi are res dos dois anteriores. No presente trabalho pathogens of great importance in trees, namely são apresentados e discutidos os parâmetros in species of the genus Quercus. -

Metacommunity Analyses of Ceratocystidaceae Fungi Across Heterogeneous African Savanna Landscapes

Fungal Ecology 28 (2017) 76e85 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Fungal Ecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/funeco Metacommunity analyses of Ceratocystidaceae fungi across heterogeneous African savanna landscapes Michael Mbenoun a, 1, Jeffrey R. Garnas b, Michael J. Wingfield a, * Aime D. Begoude Boyogueno c, Jolanda Roux a, a Department of Microbiology, Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute (FABI), University of Pretoria, Private Bag X20 Hatfield, Pretoria 0028, South Africa b Department of Zoology, Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute (FABI), University of Pretoria, Private Bag X20 Hatfield, Pretoria 0028, South Africa c Institute of Agricultural Research for Development, P.O. Box 2067, Yaounde, Cameroon article info abstract Article history: Metacommunity theory offers a powerful framework to investigate the structure and dynamics of Received 5 March 2016 ecological communities. We used Ceratocystidaceae fungi as an empirical system to explore the potential Received in revised form of metacommunity principles to explain the incidence of putative fungal tree pathogens in natural 29 September 2016 ecosystems. The diversity of Ceratocystidaceae fungi was evaluated on elephant-damaged trees across Accepted 29 September 2016 the Kruger National Park of South Africa. Multivariate statistics were then used to assess the influence of Available online 25 May 2017 landscapes, tree hosts and nitidulid beetle associates as well as isolation by distance on fungal com- Corresponding Editor: Jacob Heilmann- munity structure. Eight fungal and six beetle species were recovered from trees representing several Clausen plant genera. The distribution of Ceratocystidaceae fungi was highly heterogeneous across landscapes. Both tree host and nitidulid vector emerged as key factors contributing to this heterogeneity, while Keywords: isolation by distance showed little influence. -

Co-Adaptations Between Ceratocystidaceae Ambrosia Fungi and the Mycangia of Their Associated Ambrosia Beetles

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2018 Co-adaptations between Ceratocystidaceae ambrosia fungi and the mycangia of their associated ambrosia beetles Chase Gabriel Mayers Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Biology Commons, Developmental Biology Commons, and the Evolution Commons Recommended Citation Mayers, Chase Gabriel, "Co-adaptations between Ceratocystidaceae ambrosia fungi and the mycangia of their associated ambrosia beetles" (2018). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 16731. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/16731 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Co-adaptations between Ceratocystidaceae ambrosia fungi and the mycangia of their associated ambrosia beetles by Chase Gabriel Mayers A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Microbiology Program of Study Committee: Thomas C. Harrington, Major Professor Mark L. Gleason Larry J. Halverson Dennis V. Lavrov John D. Nason The student author, whose presentation of the scholarship herein was approved by the program of study committee, is solely responsible for the content of this dissertation. The Graduate College will ensure this dissertation is globally accessible and will not permit alterations after a degree is conferred. Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2018 Copyright © Chase Gabriel Mayers, 2018. -

Xylosandrus Compactus (Coleoptera: Scolytidae - Black Twig Borer) Is a Highly Polyphagous Pest of Woody Plants Which Has Recently Been Reported from Italy and France

EPPO, 2020 Mini data sheet on Xylosandrus compactus Added to the EPPO Alert List in 2017 – Deleted in 2020 Reasons for deletion: Xylosandrus compactus and its associated fungi have been included in EPPO Alert List for more than 3 years and during this period no particular international action was requested by the EPPO member countries. In 2020, the Working Party on Phytosanitary Regulations agreed that it could be deleted, considering that sufficient alert has been given. Why: Xylosandrus compactus (Coleoptera: Scolytidae - black twig borer) is a highly polyphagous pest of woody plants which has recently been reported from Italy and France. It probably originates from Asia and has been introduced to other parts of the world, most probably with trade of plants and wood. In parts of Italy (Lazio), serious damage has recently been observed on Mediterranean maquis plants in a natural environment. As this pest might also present a risk to many woody plants in nurseries, plantations, orchards, parks and gardens, scientists who had observed this outbreak in Lazio recommended that X. compactus should be added to the EPPO Alert List. Where: X. compactus is widely distributed in Africa, Asia and South America. It has been introduced in the Pacific Islands, New Zealand, Southeastern USA, and more recently in Europe in Italy and Southern France. X. compactus is thought to originate from East Asia. EPPO region: Italy (first found in 2011 - Campania, Lazio, Liguria, Sicilia and Toscana), France (first found in 2016 - Provence-Alpes-Côte-d’Azur region), Greece (first found in 2019), Spain (Baleares only). Africa: Benin, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Comoros, Congo, Congo (Democratic Republic of), Cote d'Ivoire, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Liberia, Madagascar, Mauritania, Mauritius, Nigeria, Reunion, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zimbabwe.