Now Streaming Everywhere: an Examination of Netflix's Global Expansion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organized Crime and Terrorist Activity in Mexico, 1999-2002

ORGANIZED CRIME AND TERRORIST ACTIVITY IN MEXICO, 1999-2002 A Report Prepared by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress under an Interagency Agreement with the United States Government February 2003 Researcher: Ramón J. Miró Project Manager: Glenn E. Curtis Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 20540−4840 Tel: 202−707−3900 Fax: 202−707−3920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://loc.gov/rr/frd/ Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Criminal and Terrorist Activity in Mexico PREFACE This study is based on open source research into the scope of organized crime and terrorist activity in the Republic of Mexico during the period 1999 to 2002, and the extent of cooperation and possible overlap between criminal and terrorist activity in that country. The analyst examined those organized crime syndicates that direct their criminal activities at the United States, namely Mexican narcotics trafficking and human smuggling networks, as well as a range of smaller organizations that specialize in trans-border crime. The presence in Mexico of transnational criminal organizations, such as Russian and Asian organized crime, was also examined. In order to assess the extent of terrorist activity in Mexico, several of the country’s domestic guerrilla groups, as well as foreign terrorist organizations believed to have a presence in Mexico, are described. The report extensively cites from Spanish-language print media sources that contain coverage of criminal and terrorist organizations and their activities in Mexico. -

Violence Within: Understanding the Use of Violent Practices Among Mexican Drug Traffickers

Violence within: Understanding the Use of Violent Practices Among Mexican Drug Traffickers By Dr. Karina García JUSTICE IN MEXICO WORKING PAPER SERIES Volume 16, Number 2 November 2019 About Justice in Mexico: Started in 2001, Justice in Mexico (www.justiceinmexico.org) is a program dedicated to promoting analysis, informed public discourse, and policy decisions; and government, academic, and civic cooperation to improve public security, rule of law, and human rights in Mexico. Justice in Mexico advances its mission through cutting-edge, policy-focused research; public education and outreach; and direct engagement with policy makers, experts, and stakeholders. The program is presently based at the Department of Political Science and International Relations at the University of San Diego (USD), and involves university faculty, students, and volunteers from the United States and Mexico. From 2005 to 2013, the program was based at USD’s Trans-Border Institute at the Joan B. Kroc School of Peace Studies, and from 2001 to 2005 it was based at the Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies at the University of California-San Diego. About this Publication: This paper forms part of the Justice in Mexico working paper series, which includes recent works in progress on topics related to crime and security, rule of law, and human rights in Mexico. All working papers can be found on the Justice in Mexico website: www.justiceinmexico.org. The research for this paper involved in depth interviews with over thirty participants in violent aspects of the Mexican drug trade, and sheds light on the nature and purposes of violent activities conducted by Mexican organized crime groups. -

Hacking Politics How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists and Suits Teamed up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet

Hacking Politics How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists and Suits Teamed Up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet EDITED BY DAVID MOON, PATRICK RUFFINI, AND DAVID SEGAL Hacking Politics THE ULTIMATE DOCUMENTATION OF THE ULTIMATE INTERNET KNOCK-DOWN BATTLE! Hacking Politics From Aaron to Zoe—they’re here, detailing what the SOPA/PIPA battle was like, sharing their insights, advice, and personal observations. Hacking How Geeks, Politics includes original contributions by Aaron Swartz, Rep. Zoe Lofgren, Lawrence Lessig, Rep. Ron Paul, Reddit’s Alexis Ohanian, Cory Doctorow, Kim Dotcom and many other technologists, activists, and artists. Progressives, Hacking Politics is the most comprehensive work to date about the SOPA protests and the glorious defeat of that legislation. Here are reflections on why and how the effort worked, but also a blow-by-blow the Tea Party, account of the battle against Washington, Hollywood, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce that led to the demise of SOPA and PIPA. Gamers, Anarchists DAVID MOON, former COO of the election reform group FairVote, is an attorney and program director for the million-member progressive Internet organization Demand Progress. Moon, Moon, and Suits Teamed Up PATRICK RUFFINI is founder and president at Engage, a leading digital firm in Washington, D.C. During the SOPA fight, he founded “Don’t Censor the to Defeat SOPA and Net” to defeat governmental threats to Internet freedom. Prior to starting Engage, Ruffini led digital campaigns for the Republican Party. Ruffini, Save the Internet DAVID SEGAL, executive director of Demand Progress, is a former Rhode Island state representative. -

Pink Unicorn Program

M T H A E Y E OUT OF THE BOX 9 P I - S 2 C 5 THEATRICS O , P 2 A 0 L 1 A presents 9 C T O R A L I C E R I P L E Y in S ' G U I L D MUSIC & LYRICS BY STEPHEN SONDHEIM BOOK BY JAMES LAPINE BOOK E L I S E F O R I E R E D I E DIRECTION A M Y E . J O N E S @ootbtheatrics Opening Night: May 15, 2019 The Episcopal Actors' Guild 1 East 29th Street Elizabeth Flemming Ethan Paulini Producing Artistic Director Associate Artistic Director present Alice Ripley* in Out of the Box Theatrics' production of By Elise Forier Edie Technical Design Dialect Coach Costume Design Frank Hartley Rena Cook Hunter Dowell Board Operator Wardrobe Supervisor Joshua Christensen Carrie Greenberg Graphic Design General Management Asst. General Management Gabriella Garcia Maggie Snyder Cara Feuer Press Representative Production Stage Management Ron Lasko Theresa S. Carroll* Directed by AMY E. JONES+ * Actors' Equity OOTB is proud to hire members of + Stage Directors and Association Choreographers Society AUTHOR'S NOTE ELISE FORIER EDIE People often ask me “how much of this play is true?” The answer is, “All of it.” Also, “None of it.” All the events in this play happened to somebody. High school students across the country have been forbidden to start Gay and Straight Alliance clubs. The school picture event mentioned in this play really did happen to a child in Florida. Families across the country are being shunned, harassed and threatened by neighbors, and they suffer for allowing their transgender children to freely express their identities. -

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By STUDIO)

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by STUDIO) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined Total # of Female + Directed by Male Directed by Male Directed by Female Directed by Female Male Female Studio Title Female + Signatory Company Network Episodes Minority Male Caucasian % Male Minority % Female Caucasian % Female Minority % Unknown Unknown Minority % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority A+E Studios, LLC Knightfall 2 0 0% 2 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC History Channel A+E Studios, LLC Six 8 4 50% 4 50% 1 13% 3 38% 0 0% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC History Channel A+E Studios, LLC UnReal 10 4 40% 6 60% 0 0% 2 20% 2 20% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC Lifetime Alameda Productions, LLC Love 12 4 33% 8 67% 0 0% 4 33% 0 0% 0 0 Alameda Productions, LLC Netflix Alcon Television Group, Expanse, The 13 2 15% 11 85% 2 15% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 Expanding Universe Syfy LLC Productions, LLC Amazon Hand of God 10 5 50% 5 50% 2 20% 3 30% 0 0% 0 0 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon I Love Dick 8 7 88% 1 13% 0 0% 7 88% 0 0% 0 0 Picrow Streaming Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Just Add Magic 26 7 27% 19 73% 0 0% 4 15% 1 4% 0 2 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Kicks, The 9 2 22% 7 78% 0 0% 0 0% 2 22% 0 0 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Man in the High Castle, 9 1 11% 8 89% 0 0% 0 0% 1 11% 0 0 Reunion MITHC 2 Amazon Prime The Productions Inc. -

Visualidad Política De América Latina En Narcos: Un Análisis a Través Del Estilo Televisivo

° www. comunicacionymedios.uchile.cl 106 Comunicación y Medios N 37 (2018) Visualidad política de América Latina en Narcos: un análisis a través del estilo televisivo Political visuality of Latin America in Narcos: an analysis through the television style Simone Rocha Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brasil [email protected] Resumen Abstract Desde la fundamentación teórica ofrecida por From the theoretical approach of the visual stu- los estudios visuales articulados al análisis del dies articulated with television style analysis, I estilo televisivo, propongo analizar visualidades intend to analyze visualities of Latin America de América Latina y de eventos históricos que and historical events on the contemporary drug tratan la problemática contemporánea de las problem exhibited in the first season of Narcos drogas exhibidas en la primera temporada de (Netflix, 2015). Based on the primary meaning Narcos (Netflix, 2015). A partir de la identifica- established by the producers, it is possible to ción del sentido tutor, definido por los realizado- understand the complex relationships between res de la serie, es posible captar las complejas crime, economy, formal politics and corruption. relaciones establecidas entre crimen, economía, política formal y corrupción. Keywords Visuality; Narcos; Latin America; Television Style. Palabras clave Visualidad; Narcos; América Latina; estilo tele- visivo. Recibido: 10-03-2018/ Aceptado: 08-06-2018 / Publicado: 30-06-2018 DOI: 10.5354/0719-1529.2018.48572 Visualidad política -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

Ted Sarandos Chief Content Officer Netflix One of Time Magazine's 100

Ted Sarandos Chief Content Officer Netflix One of Time Magazine's 100 Most influential People of 2013, Ted Sarandos has led content acquisition for Netflix since 2000. With more than 20 years’ experience in the home entertainment business, Ted is recognized as a key innovator in the acquisition and distribution of films and television programs. From its roots as a U.S. DVD subscription rental company, Netflix is now the world’s leading Internet television network with more than 50 million members in nearly 50 countries. With the 2013 releases of "House of Cards," "Hemlock Grove," "Arrested Development," "Orange is the New Black," “Turbo F.A.S.T.,” “Derek,” and “Lilyhammer,” Ted has led the transformation of Netflix into an original content powerhouse that is changing the rules of how serialized television is produced, released and distributed globally. In its first two years of releasing original series, documentary films and comedy specials, Netflix has been recognized by the film and TV industries with 45 Emmy nominations and 10 Emmy wins; an Oscar nomination; 6 Golden Globe nominations and a win; 2 Peabody Awards; 2 AFI Awards and recognition from all of the major guilds. Ted has also been producer or executive producer of several award winning and critically acclaimed documentaries and independent films, including the Emmy nominated "Outrage," and "Tony Bennett: The Music Never Ends." He is a Henry Crown Fellow at the Aspen Institute and serves on the board of Exploring The Arts, a nonprofit focused on arts in schools. He also serves on the Film Advisory Board for Tribeca and Los Angeles Film Festival, is an American Cinematheque board member and is an Executive Committee Member of the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. -

1 April 22Nd, 2013 Dear Fellow Shareholders, in Q1, We Added

April 22nd, 2013 Dear Fellow Shareholders, In Q1, we added over 3 million streaming members, bringing us to more than 36 million, who collectively enjoyed on Netflix over 4 billion hours of films and TV shows. Our summary results for Q1 2013 follow: (in millions except per share data) Q1 '12 Q2 '12 Q3 '12 Q4 '12 Q1 '13 Domestic Streaming: Net Additions 1.74 0.53 1.16 2.05 2.03 Total Members 23.41 23.94 25.10 27.15 29.17 Paid Members 22.02 22.69 23.80 25.47 27.91 Revenue $ 507 $ 533 $ 556 $ 589 $ 639 Contribution Profit* $ 72 $ 87 $ 96 $ 113 $ 131 Contribution Margin* 14.3% 16.4% 17.2% 19.2% 20.6% International Streaming: Net Additions 1.21 0.56 0.69 1.81 1.02 Total Members 3.07 3.62 4.31 6.12 7.14 Paid Members 2.41 3.02 3.69 4.89 6.33 Revenue $ 43 $ 65 $ 78 $ 101 $ 142 Contribution Profit (Loss) $ (103) $ (89) $ (92) $ (105) $ (77) Domestic DVD: Total Members 10.09 9.24 8.61 8.22 7.98 Revenue $ 320 $ 291 $ 271 $ 254 $ 243 Contribution Profit $ 146 $ 134 $ 131 $ 128 $ 113 Global: Revenue $ 870 $ 889 $ 905 $ 945 $ 1,024 Operating Income (Loss) $ (2) $ 16 $ 16 $ 20 $ 32 Net Income (Loss)** $ (5) $ 6 $ 8 $ 8 $ 3 Net Income Excluding Debt Extinguishment Loss $ - $ - $ - $ - $ 19 EPS** $ (0.08) $ 0.11 $ 0.13 $ 0.13 $ 0.05 EPS Excluding Debt Extinguishment Loss $ - $ - $ - $ - $ 0.31 Free Cash Flow $ 2 $ 11 $ (20) $ (51) $ (42) Shares (FD) 55.5 58.8 58.7 59.1 60.1 *Contribution profit & margin for prior periods reflect reclassification of marketing overhead costs to G&A **Net Income/EPS includes a $25m loss on extinguishment of debt ($16m net of tax) 1 Domestic Streaming Our U.S. -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

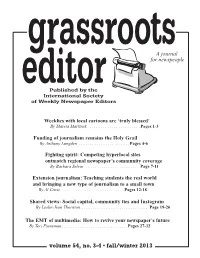

Weeklies with Local Cartoons Are 'Truly Blessed'

Weeklies with local cartoons are ‘truly blessed’ By Marcia Martinek . Pages 1-3 Funding of journalism remains the Holy Grail By Anthony Longden . Pages 4-6 Fighting spirit: Competing hyperlocal sites outmatch regional newspaper’s community coverage By Barbara Selvin . Page 7-11 Extension journalism: Teaching students the real world and bringing a new type of journalism to a small town By Al Cross . Pages 12-18 Shared views: Social capital, community ties and Instagram By Leslie-Jean Thornton . Page 19-26 The EMT of multimedia: How to revive your newspaper’s future By Teri Finneman . Pages 27-32 volume 54, no. 3-4 • fall/winter 2013 grassroots editor • fall-winter 2013 Weeklies with local Editor: Dr. Chad Stebbins Graphic Designer: Liz Ford Grassroots Editor cartoons are ‘truly blessed’ (USPS 227-040, ISSN 0017-3541) is published quarterly for $25 per year by By Marcia Martinek the International Society of Weekly Newspaper Editors, Institute of International Studies, Missouri Southern When an 8-year-old girl saw an illustration in the Altamont (New York) Enterprise depict- State University, 3950 East Newman Road, ing her church, which was being closed by the Albany Diocese, she became upset. Forest Byrd, Joplin, MO 64801-1595. Periodicals post- then the illustrator for the newspaper, had drawn the church with a tilting steeple, being age paid at Joplin, Mo., and at strangled with vines as a symbol of what was happening in the diocese. additional mailing offices. The girl wrote to the newspaper, and Editor Melissa Hale-Spencer responded to her, explaining the role of cartoons in a newspaper along with affirming the girl’s action in writing POSTMASTER: Send address changes the letter. -

Television Academy

Television Academy 2014 Primetime Emmy Awards Ballot Outstanding Directing For A Comedy Series For a single episode of a comedy series. Emmy(s) to director(s). VOTE FOR NO MORE THAN FIVE achievements in this category that you have seen and feel are worthy of nomination. (More than five votes in this category will void all votes in this category.) 001 About A Boy Pilot February 22, 2014 Will Freeman is single, unemployed and loving it. But when Fiona, a needy, single mom and her oddly charming 11-year-old son, Marcus, move in next door, his perfect life is about to hit a major snag. Jon Favreau, Director 002 About A Boy About A Rib Chute May 20, 2014 Will is completely heartbroken when Sam receives a job opportunity she can’t refuse in New York, prompting Fiona and Marcus to try their best to comfort him. With her absence weighing on his mind, Will turns to Andy for his sage advice in figuring out how to best move forward. Lawrence Trilling, Directed by 003 About A Boy About A Slopmaster April 15, 2014 Will throws an afternoon margarita party; Fiona runs a school project for Marcus' class; Marcus learns a hard lesson about the value of money. Jeffrey L. Melman, Directed by 004 Alpha House In The Saddle January 10, 2014 When another senator dies unexpectedly, Gil John is asked to organize the funeral arrangements. Louis wins the Nevada primary but Robert has to face off in a Pennsylvania debate to cool the competition. Clark Johnson, Directed by 1 Television Academy 2014 Primetime Emmy Awards Ballot Outstanding Directing For A Comedy Series For a single episode of a comedy series.