Postoperative Hypoxemia Is Common and Persistent: a Prospective Blinded Observational Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Value of Pulse Oximetry in Screening for Long-Term Oxygen Therapy Requirement

Copyright CERS Journals Ltd 1993 Eur Reaplr J, 1993, 6, 559-562 European Respiratory Journal Printed In UK • all rlghta reaerved ISSN 0903 • 1936 TECHNICAL NOTE Value of pulse oximetry In screening for long-term oxygen therapy requirement C.M. Roberts, J.R. Bugler, R. Melchor, M.R. Hetzel, S.G. Spire Value of pulse oximetry in screening for long-term oxygen therapy requirement. C.M. Dept of Thoracic Medicine, University Roberts, J.R. Bugler, R. Melcltor, M.R. Hetzel, S.G. Spiro. aRS Journals Ltd 1993. College Hospital, Gower Street, London, ABSTRACT: Pulse oximetry, combined with spirometry, was evaluated as a method UK. of selecting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) out-patients requiring definitive arterial blood gas analysis for long-term oxygen therapy (LTO'I} assess· Correspondence: C.M. Roberts The Chest Clinic ment. A relatively blgb screening arterial oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry Whipps Cross Hospital (Sao ) level was set, In order to maximize sensitivity. London Ell Ail 113 COPD out-patients att.endlng the hospital clinic over a 6 month period UK wet-e screened. Sixty bad a forced expiratory volume In one second d.S I and 26 Keywords: Chronic obstructive pulmonary bad an Sao1 s92 %. These 26 underwent arterial blood gas analysis. Nine had an ) disease arterial oxygen tension <7 .3 kPa all with an arterial carbon dioxide tension (Paco1 >6 kPa. A further eight had a Pao <8 kPa. This produced a sensitivity or 100% hypoxaemia and speclftclty or 69% for oximetry fn the detectl.on of Pao <7.3 kPa detenn.lned by oxygen therapy 1 pulse oximetry direct arterial puncture and 100% and 86% respectively for detecting a Pao1 <8 kPa. -

Nasal and Forehead Oximetry Study

ARTICLE IN PRESS Heart & Lung ■■ (2018) ■■–■■ Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Heart & Lung journal homepage: www.heartandlung.com Comparison of nasal and forehead oximetry accuracy and pressure injury in critically ill patients Marilyn Schallom, RN, PhD, CCNS a,*, Donna Prentice, RN, PhD(c), APRN-C a, Carrie Sona, RN, MSN, CCNS a, Cassandra Arroyo, MS, PhD a,b, John Mazuski, MD, PhD b a Barnes-Jewish Hospital, One Barnes-Jewish Hospital Plaza, St. Louis, MO 63110, USA b Washington University School of Medicine, 660 S Euclid Ave., St. Louis, MO 63110, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Background: In critically ill patients, clinicians can have difficulty obtaining accurate oximetry measurements. Received 31 July 2017 Objective: To compare the accuracy of nasal alar and forehead sensor measurements and incidence of Accepted 18 December 2017 pressure injury. Available online Methods: 43 patients had forehead and nasal alar sensors applied. Arterial samples were obtained at 0, 24, and 120 hours. Oxygen saturations measured by co-oximetry were compared to sensor values. Skin Keywords: was assessed every 8 hours. Pulse oximetry Results: Oxygen saturations ranged from 69.8%-97.8%, with 18% of measures < 90%. Measurements were Pressure injury Critically ill within 3% of co-oximetry values for 54% of nasal alar compared to 35% of forehead measurements. Mea- Norepineprhine surement failures occurred in 6% for nasal alar and 22% for forehead. Three patients developed a pressure Oxygen injury with the nasal alar sensor and 13 patients developed a pressure injury with the forehead sensor (χ2 = 7.68; p = .006). Conclusions: In this group of patients with decreased perfusion, nasal alar sensors provided a potential alternative for continuous monitoring of oxygen saturation. -

How Is Pulmonary Fibrosis Diagnosed?

How Is Pulmonary Fibrosis Diagnosed? Pulmonary fibrosis (PF) may be difficult to diagnose as the symptoms of PF are similar to other lung diseases. There are many different types of PF. If your doctor suspects you might have PF, it is important to see a specialist to confirm your diagnosis. This will help ensure you are treated for the exact disease you have. Health History and Exam Your doctor will perform a physical exam and listen to your lungs. • If your doctor hears a crackling sound when listening to your lungs, that is a sign you might have PF. • It is also important for your doctor to gather detailed information about your health. ⚪ This includes any family history of lung disease, any hazardous materials you may have been exposed to in your lifetime and any diseases you’ve been treated for in the past. Imaging Tests Tests like chest X-rays and CT scans can help your doctor look at your lungs to see if there is any scarring. • Many people with PF actually have normal chest X-rays in the early stages of the disease. • A high-resolution computed tomography scan, or HRCT scan, is an X-ray that provides sharper and more detailed pictures than a standard chest X-ray and is an important component of diagnosing PF. • Your doctor may also perform an echocardiogram (ECHO). ⚪ This test uses sound waves to look at your heart function. ⚪ Doctors use this test to detect pulmonary hypertension, a condition that can accompany PF, or abnormal heart function. Lung Function Tests There are several ways to test how well your lungs are working. -

Exercise-Induced Oxygen Desaturation During the 6-Minute Walk Test

medical sciences Article Exercise-Induced Oxygen Desaturation during the 6-Minute Walk Test Raghav Gupta 1,2,*, Gregg L. Ruppel 3 and Joseph Roland D. Espiritu 3 1 Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Deaconess Health System, Evansville, IN 47747, USA 2 Indiana University School of Medicine, Evansville, IN 47710, USA 3 Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO 63103, USA; [email protected] (G.L.R.); [email protected] (J.R.D.E.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 15 November 2019; Accepted: 21 January 2020; Published: 31 January 2020 Abstract: The 6-minute walk test (6MWT) is not intended to document oxygen (O2) desaturation during exertion but is often used for this purpose. Because of this, it only has modest reproducibility in determining the need for ambulatory O2 therapy in patients with cardiopulmonary disease. The diagnostic and prognostic value of detecting exertional O2 desaturation is still unknown. The aims of this study were to estimate the prevalence of O2 desaturation during a 6MWT based on pulse oximetry measurements at the beginning and end of a 6MWT in a clinical population of patients with suspected cardiopulmonary disease and to determine whether the pulmonary function test (PFT) can predict exercise-induced desaturation during a 6MWT. This retrospective cohort study reviewed the results of the 6MWT and the PFT (i.e., spirometry, lung volumes, and diffusion capacity) of all patients who were evaluated for suspected cardiopulmonary disease at an academic medical center during a 5-year study period. The patients were categorized into three groups based on the change in O saturation by pulse oximetry (SpO ) from start to end of the 6MWT: (1) SpO decreased by 3%; 2 2 2 ≥ (2) SpO unchanged ( 2 D 0%); and (3) SpO increased by 1%. -

Effect of Pressure Support Vs Unassisted Breathing Through a Tracheostomy Collar on Weaning Duration in Patients Requiring Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation

Supplementary Online Content Jubran A, Grant BJB, Duffner LA, et al. Effect of pressure support vs unassisted breathing through a tracheostomy collar on weaning duration in patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation. JAMA. 2013;309(7):doi:10.1001/jama.2013.159. eAppendix. Supplementary Online Content eFigure. Stratification and Randomization Scheme eTable 1. Definition of Respiratory Distress eTable 2. Characteristics of Patients Who Died or Were Withdrawn at Randomization eTable 3. Variables Used in Cox Proportional Hazard Model for Time to Successful Weaning for the Randomized Group eTable 4. Variables Used in Cox Proportional Hazard Model for Time to Successful Weaning for the Early-Failure Group eTable 5. Variables Used in Cox Proportional Hazard Model for Time to Successful Weaning for the Late-Failure Group This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2013 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/29/2021 eAppendix. Supplementary Online Content Effect Of Pressure Support Versus Unassisted Breathing Through A Tracheostomy Collar On Weaning Duration In Patients Requiring Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation: A Randomized Trial By Amal Jubran, MD1, Brydon J.B. Grant, MD6, Lisa A. Duffner, BS2, Eileen G. Collins, RN,PhD1,3, Dorothy M. Lanuza, RN,PhD4, Leslie A. Hoffman, RN,PhD5, , and Martin J. Tobin, MD1 From the 1Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Edward Hines Jr. Veterans Affairs Hospital, Hines IL and Loyola University of Chicago Stritch School of Medicine, Maywood IL, 2RML Specialty Hospital, Hinsdale IL, 3University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago IL, 4University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, 5University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, 6 Fayetteville VA Medical Center, Fayetteville, NC and University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY © 2013 American Medical Association. -

Clinical Practice Guideline: Improving Nasal Form and Function After

OTOXXX10.1177/0194599816683153Otolaryngology–Head and Neck SurgeryIshii et al 6831532017© The Author(s) 2010 Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Supplement Otolaryngology– Head and Neck Surgery Clinical Practice Guideline: Improving Nasal 2017, Vol. 156(2S) S1 –S30 © American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Form and Function after Rhinoplasty Surgery Foundation 2017 Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0194599816683153 http://otojournal.org Lisa E. Ishii, MD, MHS1, Travis T. Tollefson, MD, MPH2, Gregory J. Basura, MD, PhD3, Richard M. Rosenfeld, MD, MPH4, Peter J. Abramson, MD5, Scott R. Chaiet, MD, MBA6, Kara S. Davis, MD7, Karl Doghramji, MD8, Edward H. Farrior, MD9, Sandra A. Finestone, PsyD10, Stacey L. Ishman, MD, MPH11, Robert X. Murphy Jr, MD, MS, CPE12, John G. Park, MD, FCCP, FAASM13, Michael Setzen, MD14, Deborah J. Strike15, Sandra A. Walsh10, Jeremy P. Warner, MD16, and Lorraine C. Nnacheta, MPH17 Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are on knowledge gaps, practice variations, and clinical concerns disclosed at the end of this article. associated with this surgical procedure; it is not intended to be a comprehensive reference for improving nasal form and Abstract function after rhinoplasty. Recommendations in this guide- line concerning education and counseling to the patient are Objective. Rhinoplasty, a surgical procedure that alters the also intended to include the caregiver if the patient is <18 shape or appearance of the nose while preserving or en- years of age. hancing the nasal airway, ranks among the most commonly Action Statements. The Guideline Development Group made performed cosmetic procedures in the United States, with the following recommendations: (1) Clinicians should ask all pa- >200,000 procedures reported in 2014. -

MEDICAL EQUIPMENT for MULTIPLACE HYPERBARIC CHAMBERS Part I: Devices for Monitoring and Cardiac Support

European Journal of Underwater and Hyperbaric Medicine, ISSN: 1605-9204 Volume 6 No.4, December 2005 Review Articles MEDICAL EQUIPMENT FOR MULTIPLACE HYPERBARIC CHAMBERS Part I: Devices for Monitoring and Cardiac Support Jacek Kot National Centre for Hyperbaric Medicine, Institute of Maritime and Tropical Medicine, Gdynia, Medical University of Gdansk, Poland Kot J: Medical equipment for multiplace hyperbaric chambers. Part I: Devices for monitoring and cardiac support. Europ J Underwater Hyperbaric Med 2005, 6(4): 115-120. All medical devices introduced into the hyperbaric chamber should be of an appropriate design and fit for use in the hyperbaric environment and they should be certified by the manufacturer for hyperbaric conditions. However, until now only several medical devices are CE marked for usage in hyperbaric chambers. Therefore users often need to perform themselves checking of the medical equipment needed for continuation of intensive care during hyperbaric treatment. To make this task easier, this paper presents review of reports of usage of medical devices under increased pressure. Part 1 is concerning devices for monitoring and cardiac support. Part 2 will describe mechanical ventilators and Part 3 will be devoted to infusion pumps and syringes. Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy, Medical Equipment, CE Marking INTRODUCTION installing. The structure of the device is checked from a Hyperbaric chamber is an active medical device, which is point of view of raised pressure, of oxygen enriched potentially hazardous taking into accounts its application, atmosphere and of electrical supply. Furthermore, the and exposure of people inside to increased ambient function of the device is checked under hyperbaric pressure and increased partial pressure of oxygen. -

Comparing the Response of Pulse Oximetry and Regional Cerebral Oxygen Saturation to Hypoxia in Preschool Children

EXPERIMENTAL AND THERAPEUTIC MEDICINE 19: 353-358, 2020 Comparing the response of pulse oximetry and regional cerebral oxygen saturation to hypoxia in preschool children YI LU, MEIQIN DI, CHAN LI, MENGMENG CHEN, KAIMING YUAN and WANGNING SHANGGUAN Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, The Second Affiliated Hospital and Yuying Children's Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Wenzhou, Zhejiang 325027, P.R. China Received April 12, 2019; Accepted October 15, 2019 DOI: 10.3892/etm.2019.8199 Abstract. Pulse oximetry and measurement of regional cere- rcSO2 or SpO2 began to increase, rcSO2 and SpO2 values bral oxygen saturation (rcSO2) are used to monitor peripheral decreased and a significant correlation of them was observed and cerebral oxygenation, respectively. However, the response (Spearman's correlation coefficient=0.489; P=0.006). From of rcSO2 and pulse oxygen saturation (SpO2) to hypoxia in the baseline to the minimum value, compared with the preschool children has not been previously assessed. A total SpO2, the rcSO2 declined at a decreased rate (9.7±0.5% vs. of 36 preschool patients who had undergone a tonsillectomy 5.3±2.7%; P<0.001). The present clinical trial was registered [age, 4-6 years, American Society of Anesthesiologists at http://www.chictr.org.cn on 14th March 2016 (registration grade I or II] were screened and prospectively enrolled in no. ChiCTR-OOC-16008095). the present study. Hemodynamics, including rcSO2, SpO2, non-invasive blood pressure, heart rate, electrocardiogram Introduction and capnography, were continuously monitored throughout the study. Following pre-oxygenation, pressure-controlled Consecutive and non-invasive pulse oxygen saturation (SpO2) ventilation with 100% oxygen was administered through may be measured using pulse oximetry, which allows for a mask with a flow rate of 6 l/min, under total intravenous rapid identification of hypoxic state. -

Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing (CPET)

American Thoracic Society PATIENT EDUCATION | INFORMATION SERIES Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing (CPET) Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET or CPEX), also referred to as a VO2 (oxygen consumption) test, is a specialized type of stress test or exercise test that measures your exercise ability. Information about the heart and lungs is collected to understand if the body’s response to exercise is normal or abnormal. Why am I being asked to perform this test? ■ an acute medical illness or poorly controlled There are many common reasons CPET is performed chronic medical condition including to: ■ a recent heart attack (within 30 days) ■ determine a cause of unexplained shortness of ■ severely low oxygen levels breath ■ severely high blood pressure ■ assess exercise capacity ■ uncontrolled heart rhythm or heart rate problems ■ assess your risk for a planned surgical procedure Let the lab know if there has been a recent change In people who have known heart or lung disease, a in your health status such as acute infection or injury CPET may be done to: that may prevent exercising. ■ check the severity of respiratory disease (such as chronic obstructive lung disease, pulmonary How do I prepare for testing? CLIP AND COPY AND CLIP vascular disease, cystic fibrosis, and others) You should receive instructions from your healthcare ■ determine how much of a limit in exercise is due provider or the pulmonary laboratory where the to the heart or the lungs in people who have both test is being performed. These instructions may heart and lung disease vary slightly between labs. Here are some common ■ help define how much impairment or disability a instructions: person has to help guide what he or she can do ■ Wear comfortable clothing that you can exercise in, in a rehabilitation programs or to get an exercise including shoes that you can walk/run or bike in. -

Oxygen Therapy for Acute Adult Inpatients

Manual NNumber: Site: _______ ________ Oxygen Therapy for Acute Adult Inpatients Learning Module for Allied Health Staff (Category 1 and 2) Allied Health Services December 9, 2019 Oxygen Therapy Learning Module for Category 1 and 2 Staff 2 This document has been reviewed and revised in 2019 by HPSP, to reflect the changes in the Oxygen Management Guideline – Allied Health Adult Acute Care Inpatients This document has been reviewed and revised in 2015 by an Allied Health provincial multi- disciplinary group to reflect the needs of all areas of the province. It is intended for the use of adult acute care Allied Health Staff across AHS and is based on previous educational material produced in the Calgary Zone. The original document was developed in 2006 by a group of Calgary Health Region staff including Physical Therapists, Management and Program Facilitators. In 2013 it was reviewed and revised by the Allied Health Educators of the Calgary Zone, AHS. Copyright © (2015) Alberta Health Services. This material is protected by Canadian and other international copyright laws. All rights reserved. This material may not be copied, published, distributed or reproduced in any way in whole or in part without the express written permission of Alberta Health Services (please contact Health Professions, Strategy and Practice Senior Practice Lead –Physiotherapy June Norris at 780-735-3481/ [email protected]). This material is intended for general information only and is provided on an "as is", "where is" basis. Although reasonable efforts were made to confirm the accuracy of the information, Alberta Health Services does not make any representation or warranty, express, implied or statutory, as to the accuracy, reliability, completeness, applicability or fitness for a particular purpose of such information. -

British Thoracic Society Guideline for Oxygen Use in Adults in Healthcare and Emergency Settings

BMJ Open Resp Res: first published as 10.1136/bmjresp-2016-000170 on 15 May 2017. Downloaded from Guideline British Thoracic Society Guideline for oxygen use in adults in healthcare and emergency settings BRO’Driscoll, L S Howard, J Earis, V Mak, on behalf of the BTS Emergency Oxygen Guideline Development Group To cite: O’Driscoll BR, The full Guideline for oxygen use in adults fifth vital sign’ (supplemented by blood Howard LS, Earis J, et al. in healthcare and emergency settings, pub- gases when necessary), and the British Thoracic Society 1 Guideline for oxygen use in lished in Thorax provides an update to the inspired oxygen concentration should 2 adults in healthcare and 2008 BTS Emergency oxygen guideline. be recorded on the observation chart emergency settings . BMJ The following is a summary of the recom- with the oximetry result. (The other Open Resp Res 2017;4: mendations and good practice points. The vital signs are pulse rate, blood pres- e000170. doi:10.1136/ sections noted to within this summary refer sure, temperature and respiratory rate). bmjresp-2016-000170 to the full guideline sections. ○ Pulse oximetry must be available in all ▸ Additional material is locations where emergency oxygen is available. To view please visit EXECUTIVE SUMMARY used. Clinical assessment is recom- the journal (http://dx.doi.org/ ≥ 10.1136/bmjresp-2016- Philosophy of the guideline mended if the saturation falls by 3% or 000170) ✓ Oxygen is a treatment for hypoxaemia, below the target range for the patient. not breathlessness. Oxygen has not been ○ All critically ill patients outside of a The concise version of the proven to have any consistent effect on critical care area (e.g. -

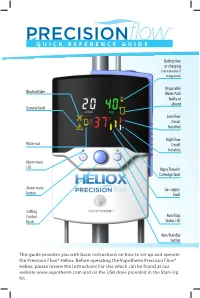

Quick Reference Guide

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE Battery low or charging (not indicative of charge level) Disposable Blocked tube Water Path faulty or absent General fault Low Flow Circuit Installed High Flow Water out Circuit Installed Alarm mute LED Vapor Transfer Cartridge fault Alarm mute Gas supply button fault Setting Control Run/Stop Knob Status LED Run/Standby button This guide provides you with basic instructions on how to set up and operate the Precision Flow® Heliox. Before operating the Vapotherm Precision Flow® Heliox, please review the Instructions For Use which can be found at our website www.vapotherm.com and on the USB drive provided in the Start-Up Kit. ALARM ICON WARNING INDICATES CAUSE ACTION ALARM ICON WARNING INDICATES CAUSE ACTION Check gas supply. If not Disconnect patient. Remove corrected, disconnect patient. GENERAL FAULT Malfunction of Cartridge and/or DPC not RUN mode: faulty disposable patient circuit. and Internal Unplug AC power, press and sensor or cartridge Check cartridge installation. – – IN FLOW sensor or control detected. Unit will not run. system component failure hold Run/Standby button for not detected. Check sensor windows are (FLASHING) 3 seconds to clear the alarm, clean. send for service. Disconnect patient. Place CARTRIDGE FAULT Gas bubbles in water Excessive gas unit into Standby. Replace GENERAL FAULT Unplug AC power, press and circulation. Unit diffusion through disposable patient circuit and O₂ sensor fault Depleted or hold Run/Standby button for continues to operate. cartridge fibers. including water path, – – IN 02 defective O₂ sensor 3 seconds to clear the alarm. cartridge & delivery tube. (FLASHING) Replace O2 sensor. Restart unit.