NASA/TM- ,,/ ,9 208270 Solar Prominence Eruption

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Formation and Evolution of a Multi-Threaded Solar Prominence

The Astrophysical Journal, 746:30 (12pp), 2012 February 10 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/746/1/30 C 2012. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. FORMATION AND EVOLUTION OF A MULTI-THREADED SOLAR PROMINENCE M. Luna1, J. T. Karpen2, and C. R. DeVore3 1 CRESST and Space Weather Laboratory NASA/GSFC, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA 2 NASA/GSFC, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA 3 Naval Research Laboratory, Washington, DC 20375, USA Received 2011 September 1; accepted 2011 November 8; published 2012 January 23 ABSTRACT We investigate the process of formation and subsequent evolution of prominence plasma in a filament channel and its overlying arcade. We construct a three-dimensional time-dependent model of an intermediate quiescent prominence suitable to be compared with observations. We combine the magnetic field structure of a three-dimensional sheared double arcade with one-dimensional independent simulations of many selected flux tubes, in which the thermal nonequilibrium process governs the plasma evolution. We have found that the condensations in the corona can be divided into two populations: threads and blobs. Threads are massive condensations that linger in the flux tube dips. Blobs are ubiquitous small condensations that are produced throughout the filament and overlying arcade magnetic structure, and rapidly fall to the chromosphere. The threads are the principal contributors to the total mass, whereas the blob contribution is small. The total prominence mass is in agreement with observations, assuming reasonable filling factors of order 0.001 and a fixed number of threads. The motion of the threads is basically horizontal, while blobs move in all directions along the field. -

Multi-Spacecraft Analysis of the Solar Coronal Plasma

Multi-spacecraft analysis of the solar coronal plasma Von der Fakultät für Elektrotechnik, Informationstechnik, Physik der Technischen Universität Carolo-Wilhelmina zu Braunschweig zur Erlangung des Grades einer Doktorin der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) genehmigte Dissertation von Iulia Ana Maria Chifu aus Bukarest, Rumänien eingereicht am: 11.02.2015 Disputation am: 07.05.2015 1. Referent: Prof. Dr. Sami K. Solanki 2. Referent: Prof. Dr. Karl-Heinz Glassmeier Druckjahr: 2016 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Dissertation an der Technischen Universität Braunschweig, Fakultät für Elektrotechnik, Informationstechnik, Physik ISBN uni-edition GmbH 2016 http://www.uni-edition.de © Iulia Ana Maria Chifu This work is distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License Printed in Germany Vorveröffentlichung der Dissertation Teilergebnisse aus dieser Arbeit wurden mit Genehmigung der Fakultät für Elektrotech- nik, Informationstechnik, Physik, vertreten durch den Mentor der Arbeit, in folgenden Beiträgen vorab veröffentlicht: Publikationen • Mierla, M., Chifu, I., Inhester, B., Rodriguez, L., Zhukov, A., 2011, Low polarised emission from the core of coronal mass ejections, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 530, L1 • Chifu, I., Inhester, B., Mierla, M., Chifu, V., Wiegelmann, T., 2012, First 4D Recon- struction of an Eruptive Prominence -

Solar Prominence Magnetic Configurations Derived Numerically

A&A 371, 328–332 (2001) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20010315 & c ESO 2001 Astrophysics Solar prominence magnetic configurations derived numerically from convection I. McKaig? Department of Mathematics, Tidewater Community College, Virginia Beach, VA 23456, USA Received 19 January 2001 / Accepted 28 February 2001 Abstract. The solar convection zone may be a mechanism for generating the magnetic fields in the corona that create and thermally insulate quiescent prominences. This connection is examined here by numerically solving a diffusion equation with convection (below the photosphere) matched to Laplace’s equation (modeling the current free corona above the photosphere). The types of fields formed resemble both Kippenhahn-Schl¨uter and Kuperus- Raadu configurations with feet that drop into supergranule boundaries. Key words. supergranulation – convection – prominences 1. Prominence models Marvelous photographs of these magnificent structures can also be found on the internet – see for example The atmosphere of the Sun, from the base of the chro- http://mesola.obspm.fr (a site run by INSU/CNRS mosphere through the corona, is structured by magnetic France) and http://sohowww.estec.esa.nl (the web fields. Presumably generated in the convection zone these site of the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory). fields break through the photosphere stimulating a vari- The field lines in the models by KS and KR are line tied ety of plasma formations, from small fibrils that outline to the photosphere (see McKaig 2001). In a previous paper convection cells to gigantic solar quiescent prominences (McKaig 2001) photospheric motions were simulated by that tower above the surface. In this paper we attempt a one-dimensional boundary condition and KS/KR type a connection between the ejection of magnetism by con- fields were obtained in the corona. -

The Sun's Dynamic Atmosphere

Lecture 16 The Sun’s Dynamic Atmosphere Jiong Qiu, MSU Physics Department Guiding Questions 1. What is the temperature and density structure of the Sun’s atmosphere? Does the atmosphere cool off farther away from the Sun’s center? 2. What intrinsic properties of the Sun are reflected in the photospheric observations of limb darkening and granulation? 3. What are major observational signatures in the dynamic chromosphere? 4. What might cause the heating of the upper atmosphere? Can Sound waves heat the upper atmosphere of the Sun? 5. Where does the solar wind come from? 15.1 Introduction The Sun’s atmosphere is composed of three major layers, the photosphere, chromosphere, and corona. The different layers have different temperatures, densities, and distinctive features, and are observed at different wavelengths. Structure of the Sun 15.2 Photosphere The photosphere is the thin (~500 km) bottom layer in the Sun’s atmosphere, where the atmosphere is optically thin, so that photons make their way out and travel unimpeded. Ex.1: the mean free path of photons in the photosphere and the radiative zone. The photosphere is seen in visible light continuum (so- called white light). Observable features on the photosphere include: • Limb darkening: from the disk center to the limb, the brightness fades. • Sun spots: dark areas of magnetic field concentration in low-mid latitudes. • Granulation: convection cells appearing as light patches divided by dark boundaries. Q: does the full moon exhibit limb darkening? Limb Darkening: limb darkening phenomenon indicates that temperature decreases with altitude in the photosphere. Modeling the limb darkening profile tells us the structure of the stellar atmosphere. -

Physics of Solar Prominences: I-Spectral Diagnostics and Non-LTE

Space Science Reviews manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Physics of Solar Prominences: I - Spectral Diagnostics and Non-LTE Modelling N. Labrosse · P. Heinzel · J.-C. Vial · T. Kucera · S. Parenti · S. Gun´ar · B. Schmieder · G. Kilper Received: date / Accepted: date Abstract This review paper outlines background information and covers recent ad- vances made via the analysis of spectra and images of prominence plasma and the increased sophistication of non-LTE (i.e., when there is a departure from Local Ther- modynamic Equilibrium) radiative transfer models. We first describe the spectral in- version techniques that have been used to infer the plasma parameters important for the general properties of the prominence plasma in both its cool core and the hotter prominence-corona transition region. We also review studies devoted to the observa- tion of bulk motions of the prominence plasma and to the determination of prominence mass. However, a simple inversion of spectroscopic data usually fails when the lines be- come optically thick at certain wavelengths. Therefore, complex non-LTE models be- come necessary. We thus present the basics of non-LTE radiative transfer theory and the associated multi-level radiative transfer problems. The main results of one- and two-dimensional models of the prominences and their fine-structures are presented. N. Labrosse Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected] P. Heinzel · S. Gun´ar Astronomical Institute, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Dr. Friˇce 298/1, CZ-25165 Ondˇrejov, Czech Republic J.-C. -

How Big? How Far?

How Big, How Far, How Hot, How Old? Deborah Scherrer, Stanford Solar Center Participants arrange imagery of Earth and space objects in order of their size, their distance from Earth, their temperature, and/or their age. By manipulating these images, students and adults represent and confront their own mental models of space and time. Target Audiences: Public education events; other Activity Time: informal science locations & 10-30 minutes activities Youth groups Age Group: Astronomy clubs Grade 5 - adult Can also be incorporated into public lectures on solar astronomy (or other topics) Could be incorporated into Image courtesy of ESA/NASA SOHO classrooms and Steele Hill Materials Needed: Choose 1 or more of the “What are your ideas?” survey sheets for your group. Make a copy of each for your participants. If you are doing this in a public talk, you can project the survey questions onto a screen. If you are doing this at a table or booth or in a classroom, you can print the imagery onto cardstock, then laminate and cut them out for manipulation by participants. A pair of scissors for each participant, if you wish them to cut out the images. (optional) Introduction Many people, adults and students alike, are familiar with the names of objects in space, but have an incomplete mental model of where those objects are in space, their relative size and scale, and how they fit into the cosmic scheme of things. Understanding the sizes and distances of celestial objects can be tricky. For instance, in our everyday experience the Moon and Sun appear as the same size, but they are drastically different in sizes because of their distances from Earth. -

Waves and Magnetism in the Solar Atmosphere (WAMIS)

METHODS published: 16 February 2016 doi: 10.3389/fspas.2016.00001 Waves and Magnetism in the Solar Atmosphere (WAMIS) Yuan-Kuen Ko 1*, John D. Moses 2, John M. Laming 1, Leonard Strachan 1, Samuel Tun Beltran 1, Steven Tomczyk 3, Sarah E. Gibson 3, Frédéric Auchère 4, Roberto Casini 3, Silvano Fineschi 5, Michael Knoelker 3, Clarence Korendyke 1, Scott W. McIntosh 3, Marco Romoli 6, Jan Rybak 7, Dennis G. Socker 1, Angelos Vourlidas 8 and Qian Wu 3 1 Space Science Division, Naval Research Laboratory, Washington, DC, USA, 2 Heliophysics Division, Science Mission Directorate, NASA, Washington, DC, USA, 3 High Altitude Observatory, Boulder, CO, USA, 4 Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, CNRS Université Paris-Sud, Orsay, France, 5 INAF - National Institute for Astrophysics, Astrophysical Observatory of Torino, Pino Torinese, Italy, 6 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Florence, Florence, Italy, 7 Astronomical Institute, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Tatranska Lomnica, Slovakia, 8 Applied Physics Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University, Laurel, MD, USA Edited by: Mario J. P. F. G. Monteiro, Comprehensive measurements of magnetic fields in the solar corona have a long Institute of Astrophysics and Space Sciences, Portugal history as an important scientific goal. Besides being crucial to understanding coronal Reviewed by: structures and the Sun’s generation of space weather, direct measurements of their Gordon James Duncan Petrie, strength and direction are also crucial steps in understanding observed wave motions. National Solar Observatory, USA Robertus Erdelyi, In this regard, the remote sensing instrumentation used to make coronal magnetic field University of Sheffield, UK measurements is well suited to measuring the Doppler signature of waves in the solar João José Graça Lima, structures. -

Total Solar Eclipses: Why I Observe Them and How You Can Too Martina B

Bridgewater Review Volume 36 | Issue 1 Article 4 May-2017 Total Solar Eclipses: Why I Observe Them and How You Can Too Martina B. Arndt Bridgewater State University, [email protected] Recommended Citation Arndt, Martina B. (2017). Total Solar Eclipses: Why I Observe Them and How You Can Too. Bridgewater Review, 36(1), 4-9. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/br_rev/vol36/iss1/4 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. 2015 NORWAY ARCTIC OCEAN GREENLAND ARCTIC OCEAN SWEDEN U. S. A. ICELAND FINLAND RUSSIA UNITED POLAND CANADA KINGDOM 1997 GERMANY UKRAINE KAZAKHSTAN 2008 FRANCE ROMANIA MONGOLIA ITALY ATLANTIC SPAIN GREECE TURKEY CHINA PACIFIC SOUTH JAPAN OCEAN AFGHANISTAN IRAQ KOREA OCEAN 2006 IRAN ALGERIA PAKISTAN LIBYA EGYPT 1998 SAUDI ARABIA INDIA MAURITANIA NIGER MALI THAILAND 2009 ANTIGUA CHAD SUDAN NIGERIA VENEZUELA ETHIOPIA MARSHALL ISLANDS CONGO KENYA INDONESIA PAPUA 2001 TANZANIA NEW GUINEA BRAZIL ANGOLA INDIAN 2010 ZAMBIA BOLIVIA OCEAN NAMIBIA FRENCH 2002 MADAGASCAR AUSTRALIA POLYNESIA SOUTH 2012 AFRICA ARGENTINA NEW ZEALAND Figure 1. Map of the Author’s Ten Research Expeditions to Observe Total Solar Eclipses: Svalbard, Norway (March 20, 2015); Australia (November 13, 2012); Tatakoto, French Polynesia (July 11, 2010); Enewetak, Marshall Islands (July 22, 2009); China (August 1, 2008); Libya (March 29, 2006); South Africa (December 4, 2002); Zambia (June 21, 2001); Antigua/Guadalupe (February 26, 1998); and Mongolia (March 9, 1997). countries in Africa (Libya, Zambia, Total Solar Eclipses: Why I Observe and South Africa); to remote atolls in French Polynesia and the Marshall Them and How You Can Too Islands; and to Australia, Mongolia, and Antigua (Figure 1). -

8-4 Asssessment 4. the Objects People Refer to As Shooting Stars Are Often Meteors Burning up in Earth's Atmosphere. If A

8-4 Asssessment 8-4.1 _______ 8. (8-4.1) Which of the following planets is always 1. (8-4.1) Which bodies are composed primarily of closer to the Sun than it is to Earth? rock and metal? a. Jupiter a. asteroids and meteors b. Mars b. comets and asteroids c. Mercury c. comets and stars d. Uranus d. stars and meteors 9. (8-4.1) Which of the following drawings below 2. (8-4.1) The planets close to the sun are… best represents the motion of a planet and its a. large and gaseous. moon around the Sun? Correct Answer: C b. large and rocky. c. small and gaseous. d. small and rocky. 3. (8-4.1) The motion of Earth is responsible for several celestial events. Which of the following events is caused by Earth revolving around the sun? a. the days in a year b. the hours in a day c. the changes in the atmosphere of Earth 10. (8-4.1)The diagram on the d. the position of the constellations in right is a picture of a _______ space a. Asteroid b. Comet 4. The objects people refer to as shooting stars c. Meteorite are often meteors burning up in Earth’s d. Meteoroid atmosphere. If a meteor does not burn up but strikes Earth, it is called ____. 11. (8-4.1) Which statement is true of both a. An asteroid asteroids and meteoroids? b. A meteorite a. They are made of frozen gases and c. A meteoroid dust. d. A satellite b. -

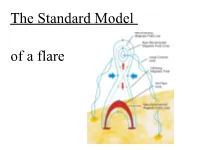

The Standard Model of the Solar Flares

The Standard Model of a flare hard X-ray 100 keV (Yohkoh) hard X-ray 20 keV (Yohkoh) microwave 6.6 GHz (OVSA) soft X-ray 1-8A (GOES) flare ribbons flare loops in the in the corona chromosphere EUV at 171A H-alpha 6563A (by TRACE) (by BBSO) a large flare observed in different wavelengths (Qiu et al.) What does trigger a flare? In the standard flare model it is expected that there is some mechanism that opens up the magnetic field. This is commonly assumed to be a filament eruption. Filaments and Prominences Filaments and prominences are cool and dense gas suspended high in the solar atmosphere, and embedded in the very hot solar corona. • When they are observed on the solar surface, they appear as dark absorption features…filaments! • When the are observed outside of the solar limb, they appears as bright features because they reflect sunlight toward us…prominences! Relatively cool gas (60,000 – 80,000 oK) compared with the low density gas of the corona The Grand Daddy Prominence A huge solar prominence observed in 1946 What does trigger a flare? Emerging flux model. Interaction between separate magnetic structures Flare model of Heyvaerts et al. Flare model of Sturrock (1980) (1977) large hot (106K) coronal loops small cool (105K) coronal loops KIS What is the structure of the low Hardi Peter corona? Peter (2001) A&A 374, 1108 Loop-Loop interactions www.astro.uni.wroc.pl/nauka/helpap/rf/1093.html Magnetic- reconnection Y. Hanaoka 1999 What does trigger a flare? Kink Instability: Tanaka (1991) proposed a model in which the rising magnetic flux bundle is already twisted and kinked prior to reaching the surface. -

Prominence and Filament Eruptions Observed by the Solar Dynamics Observatory: Statistical Properties, Kinematics, and Online Catalog

Solar Phys (2015) 290:1703–1740 DOI 10.1007/s11207-015-0699-7 Prominence and Filament Eruptions Observed by the Solar Dynamics Observatory: Statistical Properties, Kinematics, and Online Catalog P.I. McCauley1 · Y.N. Su 1,2 · N. Schanche1 · K.E. Evans1,3 · C. Su2,4 · S. McKillop1 · K.K. Reeves1 Received: 19 March 2015 / Accepted: 5 May 2015 / Published online: 26 May 2015 © Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2015 Abstract We present a statistical study of prominence and filament eruptions observed by the Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA) onboard the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO). Several properties are recorded for 904 events that were culled from the Heliophysics Event Knowledgebase (HEK) and incorporated into an online catalog for general use. These char- acteristics include the filament and eruption type, eruption symmetry and direction, appar- ent twisting and writhing motions, and the presence of vertical threads and coronal cavities. Associated flares and white-light coronal mass ejections (CME) are also recorded. Total rates are given for each property along with how they differ among filament types. We also examine the kinematics of 106 limb events to characterize the distinct slow- and fast-rise phases often exhibited by filament eruptions. The average fast-rise onset height, slow-rise duration, slow-rise velocity, maximum field-of-view (FOV) velocity, and maximum FOV acceleration are 83 Mm, 4.4 hours, 2.1kms−1, 106 km s−1, and 111 m s−2, respectively. All parameters exhibit lognormal probability distributions similar to that of CME speeds. A positive correlation between latitude and fast-rise onset height is found, which we at- tribute to a corresponding negative correlation in the average vertical magnetic field gradi- ent, or decay index, estimated from potential field source surface (PFSS) extrapolations. -

Global Properties of Solar Flares

Space Sci Rev (2011) 158: 5–41 DOI 10.1007/s11214-010-9721-4 Global Properties of Solar Flares Hugh S. Hudson Received: 30 April 2010 / Accepted: 8 November 2010 / Published online: 22 January 2011 © The Author(s) 2011. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract This article broadly reviews our knowledge of solar flares. There is a particular focus on their global properties, as opposed to the microphysics such as that needed for magnetic reconnection or particle acceleration as such. Indeed solar flares will always re- main in the domain of remote sensing, so we cannot observe the microscales directly and must understand the basic physics entirely via the global properties plus theoretical infer- ence. The global observables include the general energetics—radiation in flares and mass loss in coronal mass ejections (CMEs)—and the formation of different kinds of ejection and global wave disturbance: the type II radio-burst exciter, the Moreton wave, the EIT “wave”, and the “sunquake” acoustic waves in the solar interior. Flare radiation and CME kinetic energy can have comparable magnitudes, of order 1032 erg each for an X-class event, with the bulk of the radiant energy in the visible-UV continuum. We argue that the impulsive phase of the flare dominates the energetics of all of these manifestations, and also point out that energy and momentum in this phase largely reside in the electromagnetic field, not in the observable plasma. Keywords Flares · Coronal mass ejection 1 Introduction Carrington (1859) first reported the occurrence of a solar flare, a manifestation seen as he observed sunspots in “white light” through a small telescope.