Center on Urban Poverty and Social Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CNN Communications Press Contacts Press

CNN Communications Press Contacts Allison Gollust, EVP, & Chief Marketing Officer, CNN Worldwide [email protected] ___________________________________ CNN/U.S. Communications Barbara Levin, Vice President ([email protected]; @ blevinCNN) CNN Digital Worldwide, Great Big Story & Beme News Communications Matt Dornic, Vice President ([email protected], @mdornic) HLN Communications Alison Rudnick, Vice President ([email protected], @arudnickHLN) ___________________________________ Press Representatives (alphabetical order): Heather Brown, Senior Press Manager ([email protected], @hlaurenbrown) CNN Original Series: The History of Comedy, United Shades of America with W. Kamau Bell, This is Life with Lisa Ling, The Nineties, Declassified: Untold Stories of American Spies, Finding Jesus, The Radical Story of Patty Hearst Blair Cofield, Publicist ([email protected], @ blaircofield) CNN Newsroom with Fredricka Whitfield New Day Weekend with Christi Paul and Victor Blackwell Smerconish CNN Newsroom Weekend with Ana Cabrera CNN Atlanta, Miami and Dallas Bureaus and correspondents Breaking News Lauren Cone, Senior Press Manager ([email protected], @lconeCNN) CNN International programming and anchors CNNI correspondents CNN Newsroom with Isha Sesay and John Vause Richard Quest Jennifer Dargan, Director ([email protected]) CNN Films and CNN Films Presents Fareed Zakaria GPS Pam Gomez, Manager ([email protected], @pamelamgomez) Erin Burnett Outfront CNN Newsroom with Brooke Baldwin Poppy -

Dauntless Women in Childhood Education, 1856-1931. INSTITUTION Association for Childhood Education International, Washington,/ D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 094 892 PS 007 449 AUTHOR Snyder, Agnes TITLE Dauntless Women in Childhood Education, 1856-1931. INSTITUTION Association for Childhood Education International, Washington,/ D.C. PUB DATE [72] NOTE 421p. AVAILABLE FROM Association for Childhood Education International, 3615 Wisconsin Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20016 ($9.50, paper) EDRS PRICE NF -$0.75 HC Not Available from EDRS. PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Biographical Inventories; *Early Childhood Education; *Educational Change; Educational Development; *Educational History; *Educational Philosophy; *Females; Leadership; Preschool Curriculum; Women Teachers IDENTIFIERS Association for Childhood Education International; *Froebel (Friendrich) ABSTRACT The lives and contributions of nine women educators, all early founders or leaders of the International Kindergarten Union (IKU) or the National Council of Primary Education (NCPE), are profiled in this book. Their biographical sketches are presented in two sections. The Froebelian influences are discussed in Part 1 which includes the chapters on Margarethe Schurz, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, Susan E. Blow, Kate Douglas Wiggins and Elizabeth Harrison. Alice Temple, Patty Smith Hill, Ella Victoria Dobbs, and Lucy Gage are- found in the second part which emphasizes "Changes and Challenges." A concise background of education history describing the movements and influences preceding and involving these leaders is presented in a single chapter before each section. A final chapter summarizes the main contribution of each of the women and also elaborates more fully on such topics as IKU cooperation with other organizations, international aspects of IKU, the writings of its leaders, the standardization of curriculuis through testing, training teachers for a progressive program, and the merger of IKU and NCPE into the Association for Childhood Education.(SDH) r\J CS` 4-CO CI. -

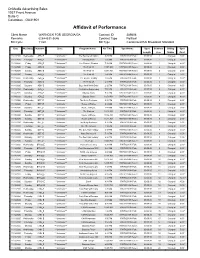

Affidavit of Performance

OnMedia Advertising Sales 1037 Front Avenue Suite C Columbus , GA31901 Affidavit of Performance Client Name WARNOCK FOR GEORGIA/GA Contract ID 285606 Remarks 62844631-3646 Contract Type Political Bill Cycle 11/20 Bill Type Condensed EAI Broadcast Standard Date Weekday Network Zone Program Name Air Time Spot Name Spot Contract Billing Spot Length Line Status Cost 11/11/2020 Wednesday AEN_E ** Unknown ** The Bourne Ultimatum 9:25 PM RWTV2013H Fork 00:00:30 1 Charged 2.00 * 11/12/2020 Thursday AEN_E ** Unknown ** Parking Wars 7:50 AM RWTV2013H Fork 00:00:30 1 Charged 2.00 * 11/13/2020 Friday AEN_E ** Unknown ** Live Rescue: Rewind 7:12 AM RWTV2014H Revert 00:00:30 1 Charged 2.00 * 11/13/2020 Friday AEN_E ** Unknown ** The First 48 11:07 AM RWTV2014H Revert 00:00:30 2 Charged 2.00 * 11/15/2020 Sunday AEN_E ** Unknown ** The First 48 12:44 PM RWTV2014H Revert 00:00:30 2 Charged 2.00 * 11/15/2020 Sunday AEN_E ** Unknown ** The First 48 1:46 PM RWTV2014H Revert 00:00:30 2 Charged 2.00 * 11/11/2020 Wednesday AEN_E ** Unknown ** The Bourne Identity 3:22 PM RWTV2013H Fork 00:00:30 3 Charged 3.00 * 11/12/2020 Thursday AEN_E ** Unknown ** The First 48 2:11 PM RWTV2013H Fork 00:00:30 3 Charged 3.00 * 11/14/2020 Saturday AEN_E ** Unknown ** Ozzy Jack World Deto 2:12 PM RWTV2014H Revert 00:00:30 3 Charged 3.00 * 11/11/2020 Wednesday AEN_E ** Unknown ** The Bourne Supremacy 7:51 PM RWTV2013H Fork 00:00:30 4 Charged 4.00 * 11/14/2020 Saturday AEN_E ** Unknown ** Storage Wars 9:17 PM RWTV2014H Revert 00:00:30 4 Charged 4.00 * 11/14/2020 Saturday AEN_E ** -

CNN/US HD PROGRAM SCHEDULE (Summer Time) July 2019

latest update:2019/5/17 11:50 CNN/US HD PROGRAM SCHEDULE (Summer Time) July 2019 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday JST 1, 8, 15, 22, 29 2, 9, 16, 23, 30 3, 10, 17, 24, 31 4, 11, 18, 25 5, 12, 19, 26 6, 13, 20, 27 7, 14, 21, 28 ET 4:00 CNN Newsroom CNN Newsroom CNNUS CNN Newsroom CNN Newsroom CNN Newsroom CNN Newsroom CNN Newsroom 15:00 with Brooke will go with Brooke Baldwin with Brooke Baldwin with Brooke Baldwin with Brooke Baldwin :30 Baldwin off the :30 air from 1AM to 5:00 CNN Newsroom ◎The Lead 7AM on ◎The Lead ◎The Lead ◎The Lead ◎The Lead CNN Newsroom 16:00 with Jake Tapper Jul. with Jake Tapper with Jake Tapper with Jake Tapper with Jake Tapper :30 30th. :30 6:00 CNN Newsroom The Situation The Situation Room The Situation Room The Situation Room The Situation Room CNN Newsroom 17:00 Room with Wolf with Wolf Blitzer with Wolf Blitzer with Wolf Blitzer with Wolf Blitzer :30 Blitzer :30 7:00 CNN Newsroom The Situation Room The Situation Room S.E.Cupp Unfiltered 18:00 with Wolf Blitzer with Wolf Blitzer :30 :30 8:00 CNN Newsroom Erin Burnett OutFront Erin Burnett OutFront Erin Burnett OutFront Erin Burnett OutFront Erin Burnett OutFront CNN Newsroom 19:00 :30 :30 9:00 CNN Newsroom ◎Anderson Cooper 360° ◎Anderson Cooper 360° ◎Anderson Cooper 360° ◎Anderson Cooper 360° ◎Anderson Cooper 360° CNN Newsroom 20:00 :30 :30 10:00 CNN Specials Cuomo Prime Time Cuomo Prime Time Cuomo Prime Time Cuomo Prime Time Cuomo Prime Time CNN Specials 21:00 :30 :30 11:00 CNN Specials CNN Tonight CNN Tonight CNN Tonight CNN Tonight -

00 Kwajalein Hourglass

00 KWAJALEIN HOURGLASS VOLUME XXIV, NO 118 U S ARMY ATOLL, MARSHALL ISLAND~ FRIDAY, JUNE 19, 1987 Jewish Leaders South Korea Demand Meeting Death From Anti- Government Protest With Pope By Jerry Schwartz Draws Warning From Prime Minister Assocwted Press Writer By M HAhn and schools and end the dIsturbances EarlIer, students threw fIrebombs, Assocwted Press Writer "I hope the pubhc clearly reahzes that stones and chunks of pavement to NEW YORK - Representatives If we should fall to overcome the pre break through pollce hnes mto the of major JewIsh orgamzatIons today SEOUL, South Korea - Pnme sent dIfficulty m a peaceful manner, surroundmg streets Faculty members demanded a meeting WIth Pope John Mmlster Lee Han-key saId today the the natIOn would plunge Into a major Issued a statement demandIng the Paul II to dISCUSS hIS agreement to government was ready to take cnsIs," he saId government respect the natIonal Will receIve Austnan PresIdent Kurt "extraordInary" measures to stop PreSIdent Reagan sent a letter to and usher In full democracy "The Waldhelm, whom they called "an un street VIOlence sweepmg the natIOn as Chun urgmg hIm not to overreact to peoples' Will has been confIrmed," repentant NazI" the fIrst death from the anti-govern street demonstrations, The New York saId the statement They said such a meetmg must be ment protests was reported Times reported today The letter The clashes today followed mas held before a scheduled ceremomal Lee's warnmg was the fIrst major called for a resumptIOn of dISCUSSIons sIve street battles -

Program Guide 2019

PROGRAM GUIDE 2019 MONDAY -FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 6:00 AM Top news stories of the day 6:00 AM Top news stories of the day 6:00 AM Top news of the day 6:15 AM APN Custom Content 6:15 AM APN Custom Content 7:00 AM HLN Morning Express 7:00 AM HLN Weekend Express 7:00 AM HLN Weekend Express 8:00 AM HLN Morning Express 7:15 AM APN Custom Content 7:15 AM APN Custom Content 8:15 AM APN Custom Content 7:30 AM Boom Cartoon (APN) 7:30 AM Boom Cartoon (APN) 9:00 AM CNNI Money 8:00 AM HLN Weekend Express 8:00 AM Inside Politics 9:45 AM APN Custom Content 8:15 AM APN Custom Content 8:15 AM APN Custom Content 9:00 AM HLN Weekend Express 9:00 AM State of the Union 10:00 AM CNNI Travel 9:15 AM APN Custom Content 9:15 AM APN Custom Content 9:30 AM CNN Vital Signs (APN) 9:30 AM CNN Vital Signs (APN) 10:30AM APN Custom Content 10:00 AM Great Big Story Show 10:00 AM Fareed Zakaria GPS 11:00 AM Vital Signs 11:30:AM APN Custom Content 10:30 AM HBO/Real Sports + APN 10:15 AM HBO Real Sports + APN 12:00 PM CNNI Quest Express 10:45 AM APN Custom Content 10:30 AM APN Custom Content 11:00 AM HLN Weekend Express 11:00 AM HLN Weekend Express 12:30 PM APN Custom Content 11:15 AM APN Custom Content 11:15 AM APN Custom Content 1:00 PM Top news with Brianna Keilar 12:00 PM CNNI Sports 12:00 PM CNNI World Sport 1:15PM APN Custom Content 12:30PM CNNI Inside (Africa, Middle East) 12:30PM HBO Real Sports + APN 2:00PM Anthony Bourdain 12:45 PM APN Custom Content 3:00 PM Top stories of the day 1:00 PM Top news stories of the day 1:00 PM APN Family 30 min 1:15 PM APN Custom -

Atlantic News

This Page © 2004 Connelly Communications, LLC, PO Box 592 Hampton, NH 03843- Contributed items and logos are © and ™ their respective owners Unauthorized reproduction 22 of this page or its contents for republication in whole or in part is strictly prohibited • For permission, call (603) 926-4557 • AN-Mark 9A-EVEN- Rev 12-16-2004 PAGE 6B | ATLANTIC NEWS | NOVEMBER 11, 2005 | VOL 31, NO 45 SEACOAST ENTERTAINMENT &ARTS | ATLANTICNEWS.COM . SUNDAY FOOTBALL SPECIAL Come watch the NFL Sunday Ticket & ESPN College Games In Our Lounge! Live Racing On Route 107 off I-95 at Exit 1 in Seabrook, NH Thursday Matinee • Friday Evening • Saturday Matinee & Evening (Schedule subject to change) 603-474-3065 www.seabrookgreyhoundpark.com Simulcasting 7 Days & 7 Nights FESTIVALS SNOWFLAKE FAIR AT FIRST BAPTIST HAMPTON | The First Baptist Church 11/14/05 5 PM 5:30 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 of Hampton, located on Winnacunnet WBZ-4 Dr. Phil (N) (Part 1 of News CBS The Insid- Ent. King of How I Met Two/Half Out of CSI: Miami “Nailed” News Late Show With Late Late Road across from the Galley Hatch (CBS) 2) (CC) News er (N) Tonight Queens Men Practice (iTV) (N) ’ (HD) (CC) David Letterman (N) Show Restaurant, will hold its annual WCVB-5 News News News ABC Wld Inside Chronicle Wife Swap NFL Football Dallas Cowboys at Philadelphia Eagles. From Lin- News (:35) Snowflake Fair on Saturday, November (ABC) (CC) (CC) (CC) News Edition (CC) “Hodge/Kolpin” (N) ’ coln Financial Field in Philadelphia. -

Star Channels, August 8

AUGUST 8 - 14, 2021 staradvertiser.com PARADISE LOST Roselyn Sánchez stars as Elena Roarke, a sophisticated and insightful woman who welcomes guests looking to fulfi l their fantasies at a mysterious luxury resort in the premiere of Fantasy Island. Roarke is assisted by Ruby (Kiara Barnes), a woman whose own island experience gave her a new lease on life, and pilot Javier (John Gabriel Rodriguez). Airing Tuesday, Aug. 10, on Fox. Enjoy original songs performed live by up and coming local artists. Hosted by Jake ShimabukuroZg]Ûef^]Zm¶ũe^ehl Mele A‘e new soundstage, Studio 1122. A SHOWCASE FOR HAWAI¶I’S SUNDAY, AUGUST 22, 7PM | olelo.org/53 olelo.org | olelo.org ASPIRING ARTISTS 53 SPECTRUM 53 & 1053 HAWAIIAN TELCOM 590242_MeleAePremiere_2_withJake_Channels.indd 1 8/3/21 1:37 PM ON THE COVER | FANTASY ISLAND Welcome (back) to ‘Fantasy Island’ ‘Da plane’ brings iconic with the Golden Gun,” 1974) as his assistant, This isn’t the first time the show has been Tattoo. The original show kicked off with two revived. In 1998, ABC brought “Fantasy Island” series back to TV made-for-television movies and continued in back to television with Malcolm McDowell a series that ran on ABC in the late 1970s and (“A Clockwork Orange,” 1971) as Mr. Roarke. early 1980s. However, the ABC edition failed to enchant By Kyla Brewer The reboot is the brainchild of writing team viewers the way the original had, and it was TV Media Liz Craft and Sarah Fain, who have worked on canceled after just 13 episodes. More re- “Angel,” “The Shield” and “Women’s Murder cently, Blumhouse Productions brought the hat if you could have exactly what Club.” The new “Fantasy Island,” a co-pro- concept to the big screen in the horror film you’ve always wanted? What if your duction between Fox Entertainment, Sony adaptation “Fantasy Island” in 2020, but it was Wwildest fantasy were to come true? panned by critics. -

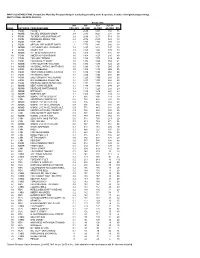

MAY'18 (LIVE+SD) FINAL Competitive Weekday Program Analysis (Excluding Breaking News & Specials, Includes All Original Programming) MAY'18 FINAL (04/30/18-05/25/18)

MAY'18 (LIVE+SD) FINAL Competitive Weekday Program Analysis (excluding breaking news & specials, includes all original programming) MAY'18 FINAL (04/30/18-05/25/18) Ranked On: HH HH P2+ A25-54 RANK NETWORK PROGRAM NAME COV AA% AA (000) AA (000) AA (000) #Tlc 1 FOXN HANNITY 3 2590 3261 650 16 2 MSNB RACHEL MADDOW SHOW 2.4 2145 2627 531 19 3 FOXN TUCKER CARLSON TONIGHT 2.4 2096 2617 519 19 4 FOXN INGRAHAM ANGLE, THE 2.4 2072 2589 523 19 5 FOXN FIVE, THE 2.1 1797 2153 379 20 6 FOXN SPECIAL RPT W/BRET BAIER 2 1771 2141 380 20 7 MSNB LAST WORD W/ L. ODONNELL 1.9 1687 2012 397 20 8 FOXN STORY, THE 1.8 1580 1943 379 20 9 MSNB ALL IN W/ CHRIS HAYES 1.6 1423 1678 336 20 10 FOXN AMERICAS NEWSROOM 1.6 1404 1627 286 40 11 FOXN FOX AND FRIENDS 1.5 1354 1575 339 60 12 FOXN FOX NEWS AT NIGHT 1.5 1272 1528 354 21 13 MSNB 11TH HOUR W/B. WILLIAMS 1.5 1284 1493 324 20 14 MSNB HARDBALL WITH C. MATTHEWS 1.5 1289 1491 285 20 15 FOXN OUTNUMBERED 1.5 1309 1478 255 20 16 FOXN YOUR WORLD W/NEIL CAVUTO 1.4 1216 1404 260 20 17 FOXN HAPPENING NOW 1.4 1232 1403 250 20 18 FOXN DAILY BRIEFING W/D.PERINO 1.4 1228 1399 256 20 19 FOXN OUTNUMBERED OVERTIME 1.4 1213 1388 262 20 20 FOXN SHEPARD SMITH REPORTING 1.4 1184 1351 254 20 21 MSNB BEAT W/ARI MELBER 1.3 1180 1330 244 20 22 MSNB DEADLINE:WHITE HOUSE 1.3 1103 1220 226 20 23 MSNB MTP DAILY 1.2 1085 1214 220 20 24 MSNB MORNING JOE 1.1 1006 1087 238 20 25 MSNB MSNBC LIVE W/ S.RUHLE 1.1 936 1002 223 20 26 CNN ANDERSON COOPER 360 0.8 760 888 280 39 27 MSNB MSNBC LIVE W/ A.VELSHI 0.9 798 876 168 19 28 MSNB MSNBC LIVE W/ H.JACKSON -

National TV Advertising Schedule September 2014 - August 2015

National TV Advertising Schedule September 2014 - August 2015 9/8-9/14 2/2-2/8 5/18-5/24 FOX News CNBC CNBC Fox & Friends, Fox News Live, Your World Worldwide Exchange, Squawk Box, Worldwide Exchange, Squawk Box, w/Neil Cavuto, The Five, Special Report, Squawk on the Street, Closing Bell, CNBC Squawk on the Street, CNBC Power O’Reilly Factor, Fox News Special, Geraldo Prime, On The Money Lunch, Closing Bell, CNBC Fast Money, at Large, Hannity, Fox Weekend Morning, CNBC Prime, CNBC Shark Tank Weekend Afternoon 2/23-3/1 CNBC 6/1-6/7 9/22-9/28 Worldwide Exchange, Squawk Box, CNN FOX News Squawk on the Street, CNBC Power Early Start, New Day, CNN Newsroom, Fox & Friends, Fox News Live, Your World Lunch, Street Signs, Closing Bell, CNBC CNN News Daytime, The Situation Room, w/Neil Cavuto, Special Report, O’Reilly Fast Money, Mad Money, CNBC Prime, On Anderson Cooper 360, Original Series/ Factor, Fox News Special, Geraldo at The Money Specials, New Day Sunday, Fareed Large, Hannity, Fox Weekend Morning, Zakaria GPS , Crossfire Weekend Afternoon 3/9-3/15 FOX News 6/15-6/21 10/6-10/12 Fox & Friends, Fox News Live, The Five, CNBC MSNBC Special Report, Huckabee, O’Reilly Factor, Squawk Box, CNBC Power Lunch, Closing Morning Joe, MSNBC Live (Daytime) Geraldo at Large, Hannity, Fox Weekend Bell, CNBC Fast Money, CNBC Prime, Morning, Weekend Afternoon CNBC Shark Tank 10/27-11/2 CNN 3/23-3/29 6/29-7/5 Early Start, CNN News Daytime, The CNBC FOX News Situation Room, Crossfire, Erin Burnett Worldwide Exchange, Squawk Box, CNBC Fox & Friends, Fox News -

Star Channels, August 29

AUGUST 29 - SEPTEMBER 4, 2021 staradvertiser.com MAMA DRAMA While the cast fi gure out their uncomfortable love triangles, we get to watch from a much more comfortable distance when Season 2 of I Love a Mama’s Boy. The show follows couples navigating the relationship between the “boys” and their mothers who just can’t let go. Premiering Sunday, Aug. 29, on TLC. CAMERA & LIGHTING FOR BEGINNERS Learn how to properly set up, light and shoot in the second of three courses taught by ¶Ōlelo’s in-house experts. To sign up, visit olelo.org/training olelo.org Video Production | Camera, Audio & Lighting | Video Editing $75 per class | Just $50 per class if you commit to and complete all 3 classes 590255_TrainingAds_2021_2in_F.indd 2 4/30/21 4:17 PM ON THE COVER | I LOVE A MAMA’S BOY Mommy dearest TLC launches Season 2 relationship — not always accompanied by room relationship, but it didn’t work out that smothering mothers; something the Season way. of “I Love a Mama’s Boy” 2 trailer does a great job of showing. Complete Trying to help in that department, mommy with awkward professions of mother-son love, dearest accompanied Kim to the lingerie sour looks from partners, mothers feeding store to pick out something special for Matt. By Rachel Jones their sons scrambled eggs and mothers insist- Needless to say, shortly thereafter, Matt and TV Media ing on being “honeymoon buddies,” even view- Kim moved out of Kelly’s house and into their ers will want to tell these moms to butt out. -

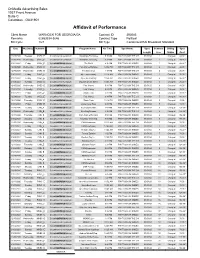

Affidavit of Performance

OnMedia Advertising Sales 1037 Front Avenue Suite C Columbus , GA31901 Affidavit of Performance Client Name WARNOCK FOR GEORGIA/GA Contract ID 293083 Remarks 62853334-3646 Contract Type Political Bill Cycle 1/21 Bill Type Condensed EAI Broadcast Standard Date Weekday Network Zone Program Name Air Time Spot Name Spot Contract Billing Spot Length Line Status Cost 12/29/2020 Tuesday CNBC_E Columbus-Valley-Auburn Worldwide Exchange 5:10 AM RW-TV20-60H THE CH 00:01:60 1 Charged 48.00 * 12/30/2020 Wednesday CNBC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA Worldwide Exchange 5:12 AM RW-TV20-60H THE CH 00:01:60 1 Charged 48.00 * 01/01/2021 Friday CNBC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA The Profit 8:16 AM RW-TV20-63H SHOES 00:01:60 1 Charged 48.00 * 12/30/2020 Wednesday CNBC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA Fast Money Halftime 12:46 PM RW-TV20-60H THE CH 00:01:60 2 Charged 26.00 * 12/30/2020 Wednesday CNBC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA The Exchange 1:17 PM RW-TV20-60H THE CH 00:01:60 2 Charged 26.00 * 01/01/2021 Friday CNBC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA Jay Leno's Garage 11:14 AM RW-TV20-63H SHOES 00:01:60 2 Charged 26.00 * 01/01/2021 Friday CNBC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA Jay Leno's Garage 11:54 AM RW-TV20-63H SHOES 00:01:60 2 Charged 26.00 * 01/05/2021 Tuesday CNBC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA Squawk on the Street 10:51 AM RW-TV20-63H SHOES 00:01:60 3 Charged 26.00 * 12/30/2020 Wednesday CNBC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA Fast Money 5:38 PM RW-TV20-60H THE CH 00:01:60 4 Charged 38.00 * 12/31/2020 Thursday CNBC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA Fast Money