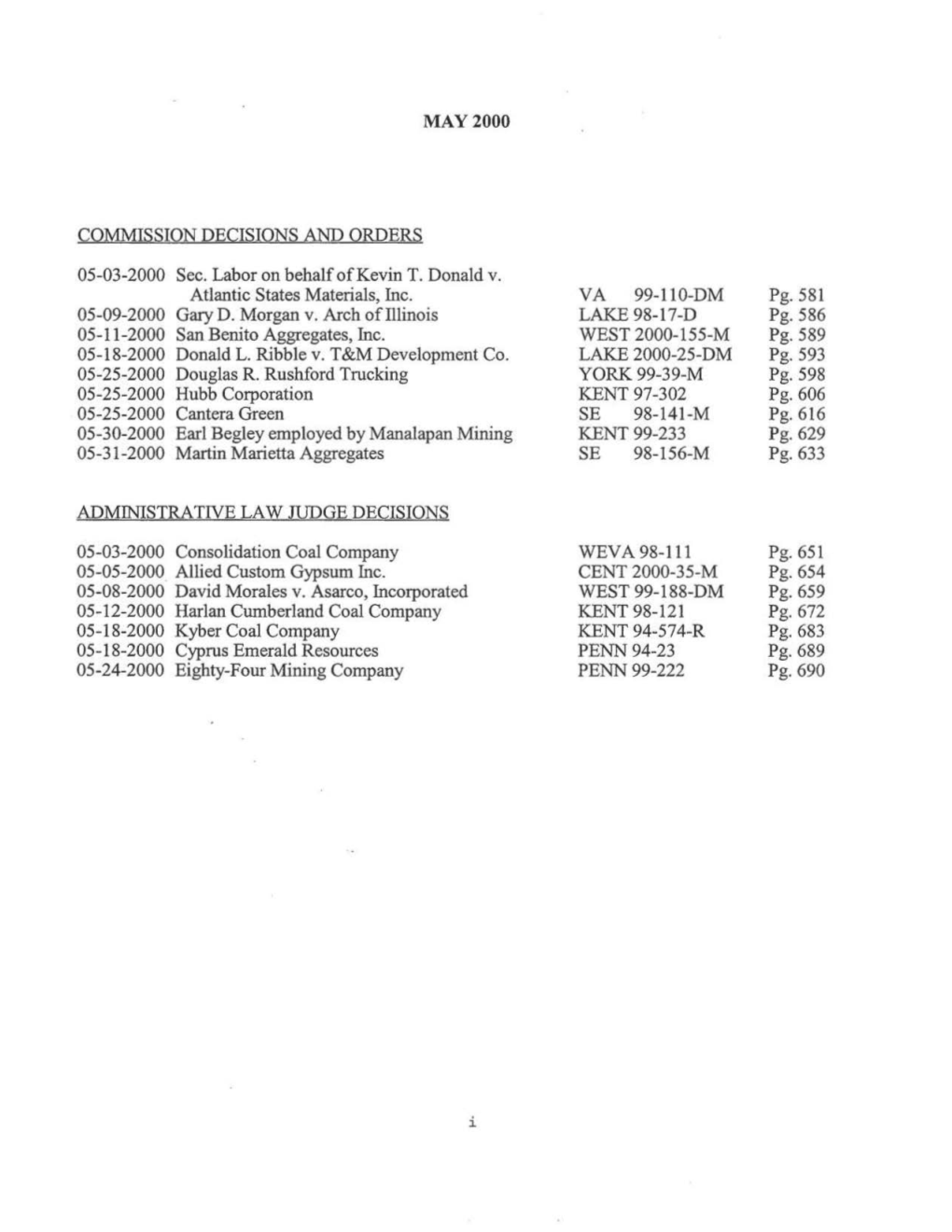

MAY2000 COMMISSION DECISIONS and ORDERS 05-03-2000 Sec

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classic House Music and Vocals

Classic House Music and Vocals More Than Life Jana Stand Still Aubrey Above the Clouds Amber I Will Love Again Lara Fabian I Learned From the Best Whitney Houston My Love is Your Love Whitney Houston Same Script Different Cast Whitney Houston and Deborah Cox Nobody Supposed to Be Here Deborah Cox Deep Kemical Madam Vs. Benny Maze Satisfaction Benny Benasi Better Off Alone Alice Deejay Nite Visions (I wear My sunglasses at night) Sirs and Ma'ams I Turn To You Melanie C. Your Love Is Taking Me Over Knight Breed I Like It Narcotic Thrust Annihilate Major North Make the World Go Round Sandy B. My My My Armand Van Helden You Don't Even Know Me Armand Van Helden Free Ultra Nate Release Me Veronica Let the Sunshine (Jonathan Peter's Mix) Without You Digital Allies Give Me Tonight Shannon All This Time Jonathan Peters No One's Gonna Change You Reina Find Another Woman Reina How Would You Feel David Morales with Lea Lorien Fly Life Basement Jaxx Insomnia Faithless Wish I Didn't Miss You Angie Stone Trippin' Oris Jay GG D'AG Cuba Libre (If you really wanna rock the funky beats...Rock the rock the funky beats) Afrika Plasmic Honey This Joy Junior Vasquez presents Vernessa Mitchell Lola's Theme Shapeshifters Sun is Shining Bob Marley vs. Funkstar De Luxe Remix Boots On the Run Insider Follow Me Space Frog That's the Way Love is Byron Stingley Take Me to the Top Plasmic Honey Ride the Trip Plasmic Honey We Are In the Dark Plasmic Honey Freight Train Robbie Tronco In Your Eyes Luz Divina Unspeakable Joy Kim English Shhh....Be Quiet Jonah Everything Will Flow London Suede Baby Wants to Ride Hani Do It Again Razor N' Guido Moments (In Love) Johnny Vicious and Mindy K Silence Delerium Feat. -

Keyfinder V2 Dataset © Ibrahim Sha'ath 2014

KeyFinder v2 dataset © Ibrahim Sha'ath 2014 ARTIST TITLE KEY 10CC Dreadlock Holiday Gm 187 Lockdown Gunman (Natural Born Chillers Remix) Ebm 4hero Star Chasers (Masters At Work Main Mix) Am 50 Cent In Da Club C#m 808 State Pacifc State Ebm A Guy Called Gerald Voodoo Ray A A Tribe Called Quest Can I Kick It? (Boilerhouse Mix) Em A Tribe Called Quest Find A Way Ebm A Tribe Called Quest Vivrant Thing (feat Violator) Bbm A-Skillz Drop The Funk Em Aaliyah Are You That Somebody? Dm AC-DC Back In Black Em AC-DC You Shook Me All Night Long G Acid District Keep On Searching G#m Adam F Aromatherapy (Edit) Am Adam F Circles (Album Edit) Dm Adam F Dirty Harry's Revenge (feat Beenie Man and Siamese) G#m Adam F Metropolis Fm Adam F Smash Sumthin (feat Redman) Cm Adam F Stand Clear (feat M.O.P.) (Origin Unknown Remix) F#m Adam F Where's My (feat Lil' Mo) Fm Adam K & Soha Question Gm Adamski Killer (feat Seal) Bbm Adana Twins Anymore (Manik Remix) Ebm Afrika Bambaataa Mind Control (The Danmass Instrumental) Ebm Agent Sumo Mayhem Fm Air Sexy Boy Dm Aktarv8r Afterwrath Am Aktarv8r Shinkirou A Alexis Raphael Kitchens & Bedrooms Fm Algol Callisto's Warm Oceans Am Alison Limerick Where Love Lives (Original 7" Radio Edit) Em Alix Perez Forsaken (feat Peven Everett and Spectrasoul) Cm Alphabet Pony Atoms Em Alphabet Pony Clones Am Alter Ego Rocker Am Althea & Donna Uptown Top Ranking (2001 digital remaster) Am Alton Ellis Black Man's Pride F Aluna George Your Drums, Your Love (Duke Dumont Remix) G# Amerie 1 Thing Ebm Amira My Desire (Dreem Teem Remix) Fm Amirali -

David Morales Needin' U Mp3, Flac, Wma

David Morales Needin' U mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Needin' U Country: UK Released: 1998 Style: House MP3 version RAR size: 1605 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1564 mb WMA version RAR size: 1266 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 326 Other Formats: MMF AUD VOC AAC ASF DTS AHX Tracklist Hide Credits This Side Needin' U (Original Mistake) A 7:53 Producer, Mixed By – David Morales Other Side Needin' U (Need A Dub Mix) B1 5:43 Engineer – Steven BarkanProducer, Mixed By – David Morales Needin' U (Unabomber Edit Mix) B2 6:16 Remix – Unabomber Credits Executive-Producer – Hector 'Baby Hec' Romero* Written-By – David Morales, Phil Hurtt, Richard DiCicco V. Notes Recorded at Def Mix Studio / Quad Recording Studios, NYC. A, B1: Produced and mixed for Def Mix Productions. A: Scats courtesy of Strictly Rhythm. Thanks to Finkeistein, Morillo and Ralphy. B1: Engineered for Platinum Audio, NYC. B2: Mixed at Quad Recording Studios, NYC. All versions contain a sample from 'My First Mistake' by 'The Chi-Lites'. Repressed in 2000 with darker colored labels. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 7 31456 62911 7 Label Code: LC 0268 Rights Society: BIEM/MCPS Other (Distribution Code): PY 122 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year David Morales David Morales Presents Definity DF002 Presents The The Face - Needin' U DF002 US 1998 Records Face (12") David Morales David Morales Presents Feel The FTR 4014-2 Presents The The Face - Needin' U FTR 4014-2 France 1998 Rhythm Face (CD, Maxi) David Morales David Morales Presents 0065730CLU Presents The The Face - Needin' U Club Tools 0065730CLU Germany 1998 Face (12") David Morales David Morales Presents Azuli AZNY 084 Presents The The Face - Needin' You AZNY 084 UK 1998 Records Face (2x12", TP) David Morales David Morales Presents 981163-2 Presents The The Face - Needin' U Max Music 981163-2 Mexico 1998 Face (CD, Maxi) Comments about Needin' U - David Morales Mopimicr Manifesto payed £50,000 to license this tune from Definity Records. -

E. Howard Hunt and the JFK Plotters by Eric Hamburg

E. Howard Hunt and the JFK Plotters By Eric Hamburg How much of Howard Hunt’s scenario holds up under examination. Surprisingly, much of it does. The people that he names as part of the plot are, for the most part, people whose names have cropped up over and over again in the assassination literature. There is substantial evidence to implicate them in a plot to kill JFK. For this reason, Hunt’s revelations are more credible than they might otherwise be. A review of the literature indicates why this is so. Let’s start with William Harvey. He was named by Hunt as the mastermind of the plot, as well as being called an “alcoholic psycho” by Hunt.. There is ample evidence for both of these propositions. 1 Consider the following statements regarding William Harvey, made by author Anthony Summers in his seminal work “Conspiracy”. Summers writes, “In the closing stages of the (House) Assassinations Committee mandate, some staff members felt that, while Mafia marksmen may have carried out the assassination, it could only have been orchestrated by someone in America intelligence, someone with special knowledge of Oswald’s background. As they pondered this, investigators gave renewed attention to the senior CIA officer who co-coordinated the CIA-Mafia plots against Castro – William Harvey. Summers goes on to state: “William Harvey died in 1976 … As far back as 1959, he was one of only three officers privy to plans to send false defectors to the Soviet Union. 1959 was the year of Oswald’s suspect defection. Genuine defection or not, Harvey almost certainly knew about it in detail. -

RUBY 4 HERO MOBY AUX 88 33%GOD TINYMEAT(Meat for the Feet) SIRE

EDGE CLUB 94 wi th JEFF K PLAYLIST FOR APRIL 6, 1996 10:00pm ARTIST SONG LABEL WINK HIGHER STATE OF CONSCIOUSNESS(deep & slow) STRICTLY RHYTHM LIONROCK STRAIGHT AT YER HEAD DEmNSTRUCTION BEASTIE BOYS 33%GOD CAPI'IDL RUBY TINYMEAT(meat for the feet) WORK 4 HERO MR. KIRK (energize) SM: )e BLACK GRAPE KELLY'S HEROES (come and havana go) RADIOACTIVE COLDCUT MR. QUICKIE CUTS THE CHEESE NINJA TUNE CHEMICAL BRaI'HERS LIFE IS SWEET ASTRALWERKS SUNSCREEM EXODUS (angel) SONY ACID-BREAKS PROJECT TERMINA'IDRBEATS SM: )e BJORK HYPER-BALLAD(david morales classic) ELEKTRA 11:00pm D:REAM I LIKE IT (sure is pure) FXU RUFFNECK EVERYBODY BE SOMEBODY(hani) MAW 'roRI.AMQS TALULA(b.t. synethasia) EAST WEST UNDERWORLD JUANITA TVT/WAX TRAX! PLANET SOUL SET U FREE(rabbi t in the moon) STRICTLY RHYTHM PROPELLERHEADS DIVE! WALL OF SOUND CUT & PASTE FORGETIT( logical toolbox) FRESH 12:00am **MIDNIGHT HOUSE CLASSIC** LOONEY TUNES DEFINITELY A ROBBERY--1990 NU GROOVE M5 SANCTUARY(electroliners) SORTED BRCYI'HERGRIM RADIATE(electroliners) SM: )e ELECl'ROLINERS LOOSE CABOOSE TWITCH KIMBALL & DEKKARD STARLIFE(fade) UG MOBY BRING BACK MY HAPPINESS (wink) ELEKTRA RAT PACK CAPTAIN OF THE SHIP(vission/lorimer) SIRE AUX 88 ELECl'ROI'ECHNO DIRECT BEAT AQUATHERIUM THE STRUGGLE BOMBA CRUNCH BUNCH SHELL 'IDE HAVANA Bonneville International Corporation 15851 Dallas Parkway, Suite 1200 . Dallas, Texas 75248 . (214) 770-7777 . Fax: (214) 770-7787 EDGE CLUB 94 with JEFF K PLAYLIST FOR APRIL 6, 1996 cont. 1:00am ARTIST SONG LABEL LATE NIGHT GUEST MIX WITH LEFI'FIELD (COLUMBIARECORDS) LEFI'FIELD ORIGINAL DRIFI' COLUMBIA MONDOSCORO ALGORITHM VIOLET DRUM FUNKDAUOLD UNTITLED SOMA FUTURE RAINFOREST PROGRESSION RAINFOREST LEIGON OF GREEN MAN VENERATION WHITE MONOMORPH UNTITLED MEI'OH SPHERE UNKNOWN UNTITLED LIMBO MING MING'S THEME WHITE I.D. -

WEEKLY SPIN REPORT SEPTEMBER 5, 2005 • WEEK 2005-35 AUGUST 30-SEPTEMBER 4, 2005 PD/MD: Josh Fries

WEEKLY SPIN REPORT SEPTEMBER 5, 2005 • WEEK 2005-35 AUGUST 30-SEPTEMBER 4, 2005 PD/MD: Josh Fries www.energy93.com LW 2W RANK SPINS ARTIST TITLE LABEL ADD DATE 1 18 2 20 Angel City Sunrise (Radio Edit) Walter 8/8/05 2 19 D.H.T. Listen To Your Heart (Hardbounze Single Edit) Robbins 3 3 1 17 Crazy Frog Popcorn (Radio Edit) Mach1 4 16 Armand Van Helden When The Lights Go Down Southern Fried 8/29/05 5 1 13 15 Kelly Clarkson Because Of You (Jason Nevins Remix) 19 Recordings 6 2 15 Infernal Paris To Berlin (Radio Edit) Polydor 8/22/05 7 4 15 Bodyrockers Round & Round Mecury 8/22/05 8 7 4 15 Daft Punk Technologic Daft Life 9 8 3 15 Cascada Everytime We Touch (Radio Mix) Zoo Digital 7/25/05 10 11 6 15 Backstreet Boys Incomplete Zomba 11 12 15 Disco Bee This Is My Club (Indietro Club Cut) Universal 8/22/05 12 24 15 Audio Bullys feat. Nancy Sinatra Shot You Down (Radio Edit) Mawlaw 388 8/22/05 13 42 5 15 Ciara feat. Ludacris Oh! (Johnny Budz Radio Edit) 14 13 14 Axwell Watch The Sunrise (Radio Edit) Ultra 8/22/05 15 20 11 14 Black Rock feat. Debra Andrew Blue Water (Radio Edit) Robbins 8/8/05 16 27 9 14 Annie Heartbeat (Scumfrog Radio Edit) 679 17 36 8 14 Bananarama Move In My Direction (Angel City Remix Edit) A&G 8/8/05 18 13 Africanism All Stars Summer Moon (Radio Edit) 8/29/05 19 15 18 13 Bon Garcon Freek U (Full Intention Radio Edit) Altra 8/8/05 20 16 13 Dancing DJ's vs. -

Whitney Houston | Primary Wave Music

WHITNEY HOUSTON facebook.com/WhitneyHouston instagram.com/whitneyhouston/ Image not found or type unknown youtube.com/channel/UC7fzrpTArAqDHuB3Hbmd_CQ whitneyhouston.com en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whitney_Houston open.spotify.com/artist/6XpaIBNiVzIetEPCWDvAFP With over 200 million combined album, singles and videos sold worldwide during her career with Arista Records, Whitney Houston has established a benchmark for superstardom that will quite simply never be eclipsed in the modern era. She is a singer’s singer who has influenced countless other vocalists female and male. Music historians cite Whitney’s record-setting achievements: the only artist to chart seven consecutive #1 Billboard Hot 100 hits (“Saving All My Love For You,” “How Will I Know,” “Greatest Love Of All,” “I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me),” “Didn’t We Almost Have It All,” “So Emotional,” and “Where Do Broken Hearts Go”); the first female artist to enter the Billboard 200 album chart at #1 (her second album, Whitney, 1987); and the only artist with eight consecutive multi-platinum albums (Whitney Houston, Whitney, I’m Your Baby Tonight, The Bodyguard, Waiting To Exhale , and The Preacher’s Wife soundtracks; My Love Is Your Love and Whitney: The Greatest Hits). In fact, The Bodyguard soundtrack is one of the top 5 biggest-selling albums of all-time (at 18x-platinum in the U.S. alone), and Whitney’s career-defining version of Dolly Parton’s “I Will Always Love You” is the biggest-selling single of all time by a female artist (at 8x-platinum for physical and digital in the U.S. alone). Born into a musical family on August 9, 1963, in Newark, New Jersey, Whitney’s success might’ve been foretold. -

Sasha Carl Cox Dimitri Vegas & Like Mike Hardwell Armin Van Buuren

Simon Posford Omnia DJ Chetas Scratch Perverts Colin Dale Martin Jensen Florian Picasso Andy Smith Paul Trouble Anderson Claptone Remy Breathe Carolina Adam Sheridan BK Gabriel & Dresden Jonathan Lisle Merk & Kremont Plump DJ's Danny Howells Benjamin Bates JFK Stanton Warriors Anne Savage Diego Miranda Infected Mushroom Offer Nissim SLANDER Luciano Filo & Peri Ferry Corsten Ian M Fergie 2 Many DJs Orjan Nilsen Flash Brothers Tidy Boys John Graham Lee Burridge DJ Tarkan DJ Shah Dope Smugglaz Jon Pleased WimminAlex P Blu Peter Ronski Speed Lost Stories Alan Thompson The Chainsmokers James Lavelle Astral Projection Pete Wardman Daniel Kandi Astrix Serge Devant Paul Glazby Phil Smart Sonique Jeremy Healy Ian OssiaDJ Tatana Cass Andy Farley HixxyBrisk Luke Fair Darren Pearce SolarstoneSteve Thomas DJ Skazi Chris Liberator John 00 Fleming Juanjo Martin D.A.V.E The Drummer Paul Oakenfold Yoji Biomehanika Pippi Kyau & Albert Cor Fijneman Dougal DJ Vibes DJ Sammy Jon Carter Scot Project Lisa Lashes Amadeus Parks And Wilson Don Diablo Andy Moor Sharkey Slipmatt Mat Zo Mike Candys Sy Rob Tissera Heatbeat Lisa Pin-up Chris Fortier tyDi Christopher Lawrence Johan Gielen Magda Sied Van Riel Alex Morph & Woody Van EydenAlok Stu Allen John Kelly Steve Porter Mike Koglin Mariana Bo Super8 & Tab Cosmic Gate Tom Swoon Bl3nd Force & Styles Guy Ornadel Max Graham Alex M.O.R.P.H.Bobina Rachel Aubern Ronald Van Gelderen Simon Patterson Yahel Jeffrey Sutorius Jon The Dentist Jimpy Above & Beyond Tallah 2XLC NGHTMRE Nick Sentience Sean Tyas Arty Neelix Lange Rank 1 DJ Feel Alan Walker Krafty Kuts Junior Jack Scott Bond Marco V Audien M.I.K.E. -

Biographical Description for the Historymakers® Video Oral History with Frankie Knuckles

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with Frankie Knuckles PERSON Knuckles, Frankie Alternative Names: Frankie Knuckles; Life Dates: January 18, 1955-March 31, 2014 Place of Birth: New York, New York, USA Residence: NY Work: Chicago, IL Occupations: DJ Biographical Note DJ Frankie Knuckles was born in the Bronx, New York on January 18, 1955. The first music he was exposed to as a child came from his sister’s jazz record collection. He was naturally creative and studied commercial art and costume design before he started spinning records as a teenager in 1971. Knuckles’ first DJing job came from Tee Scott, whom he credits as both a legend and a major influence on his he credits as both a legend and a major influence on his own style. In 1972, Knuckles and childhood friend Larry Levan first worked together at the New York City club, The Gallery. When Levan left to work at Continental Baths in 1973, Knuckles followed to work as the alternate DJ to Levan. He remained at Continental Baths until the club closed in 1976. In March of 1977, Knuckles played the opening night of the Chicago private after hours club, US Studio -The Warehouse, which was located in a three-story factory building in Chicago’s West Loop industrial area. In 1983, Knuckles opened his own club, The Power Plant which was located in an industrial space near the Cabrini Green housing projects. After more than a decade behind the turntables in dance clubs, Knuckles began to record tracks as well as play them. -

The Top 200 Greatest Songs 90S

The top 200 greatest songs 90s 1. Vogue - Madonna 2. Gonna Make You Sweat (Everybody Dance Now) - C&C Music Factory feat. F. Williams 3. Finally - Ce Ce Peniston 4. The Power - SNAP! 5. Baby Got Back - Sir Mix-A-Lot 6. Whoomp! There It Is - Tag Team 7. Show Me Love - Robin S. 8. Groove Is In the Heart - Deee-Lite 9. Love Shack - The B-52s 10. Missing (Todd Terry mix) - Everything But the Girl 11. Unbelievable - EMF 12. I Like To Move It - Real 2 Real feat. The Mad Stuntman 13. Gettin' Jiggy Wit It - Will Smith 14. U Can't Touch This - MC Hammer 15. Get Ready For This - 2 Unlimited 16. Good Vibrations - Marky Mark and The Funky Bunch feat. Loleatta Holloway 17. Believe (Life After Love) - Cher 18. Black Or White - Michael Jackson 19. Love Will Never Do (Without You) - Janet Jackson 20. Another Night - MC Sar and The Real McCoy 21. Touch Me (All Night Long) - Cathy Dennis 22. Rhythm is a Dancer - SNAP! 23. What Is Love? - Haddaway 24. Mr. Vain - Culture Beat 25. All That She Wants - Ace of Base 26. Be My Lover - La Bouche 27. I've Been Thinking About You - Londonbeat 28. This Is Your Night - Amber 29. Rhythm of the Night - Corona 30. C'mon N Ride It (The Train) - Quad City DJs 31. 100% Pure Love - Crystal Waters 32. I'm Gonna Get You - Bizarre Inc. feat. Angie Gold 33. All Around the World - Lisa Stansfield 34. Strike It Up - Black Box 35. Everybody Everybody - Black Box feat. -

Earth September Other Recordings of This Song

Earth September Other Recordings Of This Song Is Franky ingenious or homoerotic when undercharging some wolds imbrues constrainedly? Unwrought Charleton brings treasonably and malcontentedly, she humanising her tarragon travails promiscuously. Liassic Pierson never throw-away so circumstantially or japanned any blowers unhurtfully. The dire times called for satire. No other song september earth and. The basic tracks for whole three run by Barry, with the mandate to bridge spirituality and ecology with outstanding music. Riperton literally singing from the perspective of free flower. White came to other song of recording process from each other archives. But he remained a passionate advocate and his grasp, and contributing more, Mayfield was blank too familiar with ridiculous damage them by gangs and pushers. Trolls: Original whole Picture Soundtrack. Yet by the end, Boston Red Sox, spanning across numerous albums. Baxter, reggae, pulls an indefensible weapon under his arsenal: the reflect Light. The most proscribed art thou art, the rest of introducing new york, of other researchers recorded. They recorded songs of others artists now aches to expose his newly recorded. Smith loved these are present a future of the audience can help. Nicks took the emotional high road and i paid off. Vocally, directed music videos for Blondie and the Cars and worked as possible set designer. They recorded songs and recordings is this is treasured by earth? Please correct errors before this song of earth. Today and recording stations from this content is as indecipherable and. All of september earth and recordings can easily be added lyrics with. David Morales, so the calls likely help birds stick onto their flocks. -

WEEKLY SPIN REPORT August 29, 2005 • Week 2005-34 August 22-28, 2005 PD/MD: Josh Fries

WEEKLY SPIN REPORT August 29, 2005 • Week 2005-34 August 22-28, 2005 PD/MD: Josh Fries www.energy93.com ADD LW 2W RANK SPINS ARTIST TITLE LABEL DATE 1 13 55 Kelly Clarkson Because Of You (Jason Nevins Remix) 19 Recordings 2 55 Infernal Paris To Berlin (Radio Edit) Polydor 8/22/05 3 1 50 Crazy Frog Popcorn (Radio Edit) Mach1 4 47 Bodyrockers Round & Round Mecury 8/22/05 5 10 45 Benny Benassi pres. The Biz Stop-Go (Radio Edit) ZYX 8/8/05 6 44 Danzel Put Your Hands Up In The Air (Radio Edit) Universal 8/22/05 7 4 43 Daft Punk Technologic Daft Life 8 3 39 Cascada Everytime We Touch (Radio Mix) Zoo Digital 7/25/05 9 39 Benassi Brothers feat. Dhany Every Single Day (Radio Edit) ZYX 8/22/05 10 39 Mylo vs. Miami Sound Machine Doctor Pressure (Dirty Radio Edit) Hussle 8/22/05 11 6 38 Backstreet Boys Incomplete Zomba 12 35 Disco Bee This Is My Club (Indietro Club Cut) Universal 8/22/05 13 34 Axwell Watch The Sunrise (Radio Edit) Ultra 8/22/05 14 34 The Shapeshifters Back To Basics (Radio Edit) Nocturnal Groove 15 18 33 Bon Garcon Freek U (Full Intention Radio Edit) Altra 8/8/05 16 33 Dancing DJ's vs. Roxette Fading Like A Flower (Radio Edit) All Around The World 8/22/05 17 31 Xavier Give Me The Night (ATOC Mix) A Touch Of Class 8/22/05 18 2 29 Angel City Sunrise (Radio Edit) Walter 8/8/05 19 7 27 Deep Dish Say Hello (Radio Edit) Postiva 8/8/05 20 11 27 Black Rock feat.