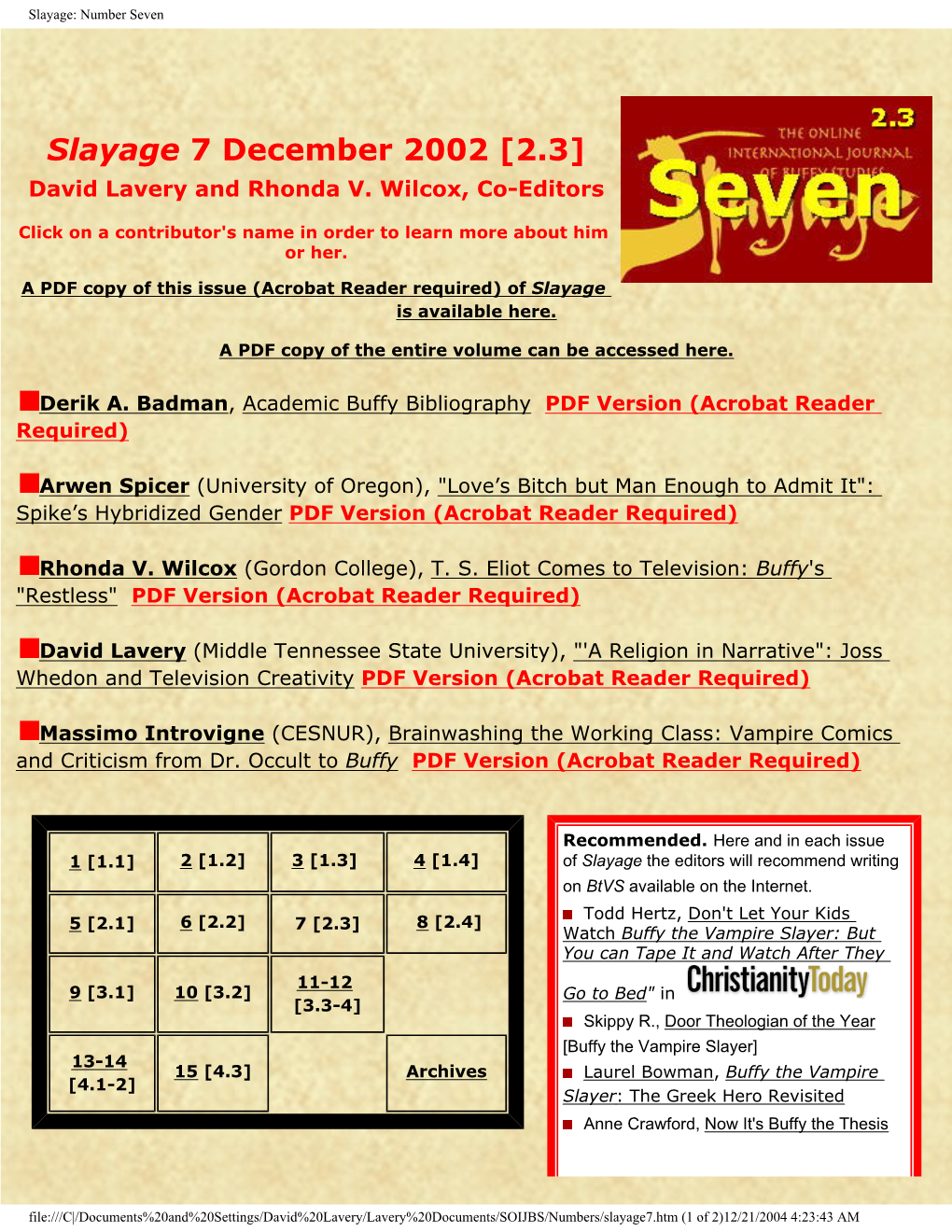

Slayage 7 December 2002 [2.3] David Lavery and Rhonda V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MGM-Halloween-3

S CHOLASTIC ELT READERS A FREE RESOURCE FOR TEACHERS! HALLOWEEN–EXTRA Level 1 This level is suitable for students who have been learning English for at least a year and up to two years. It corresponds with the Common European Framework level A1. Suitable for users of CLICK magazine. SYNOPSIS Sunnydale is a small town in California. The action centres It’s Halloween. Buffy and friends hire costumes and take around the High School. Buffy and her friends are students and children out trick-or-treating (see Fact File 2). Everyone’s having Rupert Giles, Buffy’s Watcher or guide, is the librarian. Buffy, the fun. But there’s someone new in Sunnydale who wants to spoil Chosen One, has been sent to Sunnydale because the entrance their fun. His name is Ethan, he’s opened a Costume Shop and to Hell – the Hellmouth – is in the basement of the school. he has evil plans. Ethan casts a spell (he’s actually a sorcerer). The show combines comedy, tragedy, martial arts, romance Whatever costume people hired from him, that’s what they turn and horror. The stories also deal with teenage issues of love, into. Vampire-slaying Buffy loses her powers and becomes a self-esteem and planning a future, and use the fights with cowardly noblewoman from 1775. Willow becomes a ghost and supernatural forces as metaphors for emotional anxieties. Xander turns into a real-life soldier. The vampires are delighted. Halloween is Episode 6 from Series 2, so it’s quite near the Buffy and friends find themselves imprisoned in an old beginning. -

A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected]

Student Research and Creative Works Book Collecting Contest Essays University of Puget Sound Year 2015 The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected] This paper is posted at Sound Ideas. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/book collecting essays/6 Krista Silva The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works I am an inhabitant of the Whedonverse. When I say this, I don’t just mean that I am a fan of Joss Whedon. I am sincere. I live and breathe his works, the ever-expanding universe— sometimes funny, sometimes scary, and often heartbreaking—that he has created. A multi- talented writer, director and creator, Joss is responsible for television series such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer , Firefly , Angel , and Dollhouse . In 2012 he collaborated with Drew Goddard, writer for Buffy and Angel , to bring us the satirical horror film The Cabin in the Woods . Most recently he has been integrated into the Marvel cinematic universe as the director of The Avengers franchise, as well as earning a creative credit for Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. My love for Joss Whedon began in 1998. I was only eleven years old, and through an incredible moment of happenstance, and a bit of boredom, I turned the television channel to the WB and encountered my first episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer . I was instantly smitten with Buffy Summers. She defied the rules and regulations of my conservative southern upbringing. -

Copyright by Jason Todd Craft 2004 the Dissertation Committee for Jason Todd Craft Certifies That This Is the Approved Version of the Following Dissertation

Copyright by Jason Todd Craft 2004 The Dissertation Committee for Jason Todd Craft Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Fiction Networks: The Emergence of Proprietary, Persistent, Large- Scale Popular Fictions Committee: Adam Z. Newton, Co-Supervisor John M. Slatin, Co-Supervisor Brian A. Bremen David J. Phillips Clay Spinuzzi Margaret A. Syverson Fiction Networks: The Emergence of Proprietary, Persistent, Large- Scale Popular Fictions by Jason Todd Craft, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2004 Dedication For my family Acknowledgements Many thanks to my dissertation supervisors, Dr. Adam Zachary Newton and Dr. John Slatin; to Dr. Margaret Syverson, who has supported this work from its earliest stages; and, to Dr. Brian Bremen, Dr. David Phillips, and Dr. Clay Spinuzzi, all of whom have actively engaged with this dissertation in progress, and have given me immensely helpful feedback. This dissertation has benefited from the attention and feedback of many generous readers, including David Barndollar, Victoria Davis, Aimee Kendall, Eric Lupfer, and Doug Norman. Thanks also to Ben Armintor, Kari Banta, Sarah Paetsch, Michael Smith, Kevin Thomas, Matthew Tucker and many others for productive conversations about branding and marketing, comics universes, popular entertainment, and persistent world gaming. Some of my most useful, and most entertaining, discussions about the subject matter in this dissertation have been with my brother, Adam Craft. I also want to thank my parents, Donna Cox and John Craft, and my partner, Michael Craigue, for their help and support. -

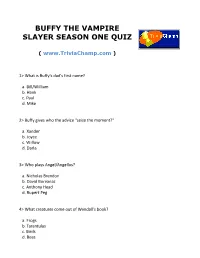

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Season One Quiz

BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER SEASON ONE QUIZ ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> What is Buffy's dad's first name? a. Bill/William b. Hank c. Paul d. Mike 2> Buffy gives who the advice "seize the moment?" a. Xander b. Joyce c. Willow d. Darla 3> Who plays Angel/Angellus? a. Nicholas Brendon b. David Boreanaz c. Anthony Head d. Rupert Peg 4> What creatures come out of Wendall's book? a. Frogs b. Tarantulas c. Birds d. Bees 5> Under Moloch's direction, what does Dave try to do to Buffy? a. Electrocute her b. Kiss her c. Stab her d. Hang her 6> Who steps in to take Marcie away? a. Angel b. Vampires c. Sunnydale Police Department d. The FBI 7> According to Giles, the earth began as what type of place? a. A home for demons b. A land for mortals c. A wasteland d. A paradise 8> What was Buffy's biology teacher's name? a. Mr. Smith b. Dr. Gregory c. Dr. Paulson d. Mr. Herring 9> What is the name of Buffy's first watcher? a. Signer b. Wilford c. Merrick d. Giles 10> Who gives Buffy a cross necklace? a. Spike b. Giles c. Cordelia d. Angel 11> What was principal Flutie's first name? a. Bob b. Ralph c. Steve d. Roy 12> What of Buffy's does Cordelia say is "over?" a. Her hairstyle b. Her shoes c. Her earrings d. Her nail polish 13> What was the name of the invisible girl? a. Marcia Craig b. Meg Stevens c. -

The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 2010 "Just a Girl": The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007 Tamy Burnett University of Nebraska at Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Burnett, Tamy, ""Just a Girl": The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007" (2010). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 27. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. “JUST A GIRL”: THE COMMUNITY-CENTERED CULT TELEVISION HEROINE, 1995-2007 by Tamy Burnett A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English (Specialization: Women‟s and Gender Studies) Under the Supervision of Professor Kwakiutl L. Dreher Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2010 “JUST A GIRL”: THE COMMUNITY-CENTERED CULT TELEVISION HEROINE, 1995-2007 Tamy Burnett, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2010 Adviser: Kwakiutl L. Dreher Found in the most recent group of cult heroines on television, community- centered cult heroines share two key characteristics. The first is their youth and the related coming-of-age narratives that result. -

Undead, Gothic, and Queer: the Allure of Buffy

Book Reviews UNDEAD, GOTHIC, AND QUEER: THE ALLURE OF BUFFY by Pamela O’Donnell Elena Levine & Lisa Parks, eds., UNDEAD TV: ESSAYS ON BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007. 209p. bibl. index. notes. ISBN 978-0-8223-4043-0. Rebecca Beirne, ed., TELEVISING QUEER WOMEN: A READER, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008. 25p. bibl. index. notes. ISBN 0-230-60080-8. Benjamin A. Brabon & Stéphanie Genz, eds., POSTFEMINIST GOTHIC: CRITICAL INTERVENTIONS IN CONTEMPORARY CULTURE, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. 89p. index. notes. ISBN 0-230-00542-X. Buffy the Vampire Slayer( BtVS) died twice in the course of the series. canceled, expired material for maxi- may well be the most analyzed televi- Perhaps more than any other televi- mum return” (p.5). Can anyone say sion show in the history of the me- sion show, BtVS deserves to be called Knight Rider? dium. Try to name another series that “undead TV,” the title chosen by Elana Because the introduction raises so has its own academic conference or its Levine and Lisa Parks for their anthol- many interesting points about BtVS’s own peer-reviewed journal. A quick ogy of eight essays exploring the cul- afterlife — including how the show’s search of Amazon.com turns up more tural impact of BtVS (p.3). move from the WB to UPN may have than a dozen scholarly volumes about doomed the two “netlets” — it’s frus- the show — from the ground-breaking In the acknowledgements section trating to discover that very few of the Why Buffy Matters to the soon-to-be- of Undead TV: Essays on Buffy the Vam- essays use this as a point of departure published Buffy Goes Dark: Essays on pire Slayer, Levine and Parks note that for their analysis.2 Indeed, more than the Final Two Seasons. -

Buffy at Play: Tricksters, Deconstruction, and Chaos

BUFFY AT PLAY: TRICKSTERS, DECONSTRUCTION, AND CHAOS AT WORK IN THE WHEDONVERSE by Brita Marie Graham A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English MONTANA STATE UNIVERSTIY Bozeman, Montana April 2007 © COPYRIGHT by Brita Marie Graham 2007 All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL Of a thesis submitted by Brita Marie Graham This thesis has been read by each member of the thesis committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English usage, format, citations, bibliographic style, and consistency, and is ready for submission to the Division of Graduate Education. Dr. Linda Karell, Committee Chair Approved for the Department of English Dr. Linda Karell, Department Head Approved for the Division of Graduate Education Dr. Carl A. Fox, Vice Provost iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it availably to borrowers under rules of the Library. If I have indicated my intention to copyright this thesis by including a copyright notice page, copying is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this thesis in whole or in parts may be granted only by the copyright holder. Brita Marie Graham April 2007 iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In gratitude, I wish to acknowledge all of the exceptional faculty members of Montana State University’s English Department, who encouraged me along the way and promoted my desire to pursue a graduate degree. -

Death As a Gift in J.R.R Tolkien's Work and Buffy the Vampire Slayer

Journal of Tolkien Research Volume 10 Issue 1 J.R.R. Tolkien and the works of Joss Article 7 Whedon 2020 Death as a Gift in J.R.R Tolkien's Work and Buffy the Vampire Slayer Gaelle Abalea Independant Scholar, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Abalea, Gaelle (2020) "Death as a Gift in J.R.R Tolkien's Work and Buffy the Vampire Slayer," Journal of Tolkien Research: Vol. 10 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch/vol10/iss1/7 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Christopher Center Library at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Tolkien Research by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Abalea: Death as a Gift in Tolkien and Whedon's Buffy DEATH AS A GIFT IN J.R.R TOLKIEN’S WORK AND BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER “Love will bring you to your gift” is what Buffy is told by a spiritual being under the guise of the First Slayer in the Episode “Intervention” (5.18). The young woman is intrigued and tries to learn more about her gift. The audience is hooked as well: a gift in this show could be a very powerful artefact, like a medieval weapon, and as Buffy has to vanquish a Goddess in this season, the viewers are waiting for the guide to bring out the guns. -

It Started with a Girl’

‘It started with a girl’ Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Angel en The WB Television Network Auteur Pim Razenberg Opleiding Film- en Televisiewetenschap Universiteit Utrecht Cursus Televisiegenres (2011) It Started With A Girl Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Angel en The WB Inhoud Inleiding ..................................................................................................................................... 3 1. It started with a girl: Het begin van Buffy en Angel ............................................................... 6 2. Vergelijking van Buffy en Angel ............................................................................................ 9 2.1 Concept ............................................................................................................................. 9 2.2 Overeenkomsten ............................................................................................................. 10 2.3 Verschillen in thematiek ................................................................................................. 11 2.4 Filmische verschillen ...................................................................................................... 13 3. Impact van Buffy en Angel op The WB ................................................................................ 16 4. Conclusie .............................................................................................................................. 18 Audiovisuele Media ................................................................................................................ -

Decolonizing the Body of the Chosen One: the Bodily Performance of Anakin Skywalker, Buffy Summers, and T'challa

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2019 Decolonizing the Body of the Chosen One: The Bodily Performance of Anakin Skywalker, Buffy Summers, and T'Challa Alise M. Wisniewski University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the American Film Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, and the American Popular Culture Commons Recommended Citation Wisniewski, Alise M., "Decolonizing the Body of the Chosen One: The Bodily Performance of Anakin Skywalker, Buffy Summers, and T'Challa" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1632. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1632 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Decolonizing the Body of the Chosen One: The Bodily Performance of Anakin Skywalker, Buffy Summers, and T’Challa ________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver _______ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _______ by Alise M. Wisniewski June 2019 Advisor: Dr. Donna Beth Ellard ©Copyright by Alise M. Wisniewski 2019 All Rights Reserved Author: Alise M. Wisniewski Title: Decolonizing the Body of the Chosen One: The Bodily Performance of Anakin Skywalker, Buffy Summers, and T’Challa Advisor: Dr. Donna Beth Ellard Degree Date: June 2019 Abstract This thesis engages the figure of the Chosen One in fantasy literature. -

A PDF Copy of This Issue of Slayage Is Available Here

Slayage: Number Six Slayage 6 September 2002 [2.2] David Lavery and Rhonda V. Wilcox, Co-Editors Click on a contributor's name in order to learn more about him or her. A PDF copy of this issue (Acrobat Reader required) of Slayage is available here. A PDF copy of the entire volume can be accessed here. J. Gordon Melton (University of California, Santa Barbara), Images from the Hellmouth: Buffy the Vampire Slayer Comic Books 1998-2002 PDF Version (Acrobat Reader Required) Reid B. Locklin (Boston University), Buffy the Vampire Slayer and the Domestic Church: Re-Visioning Family and the Common Good PDF Version (Acrobat Reader Required) Frances Early (Mount St. Vincent University), Staking Her Claim: Buffy the Vampire Slayer as Transgressive Woman Warrior PDF Version (Acrobat Reader Required) David Lavery (Middle Tennessee State University), "Emotional Resonance and Rocket Launchers": Joss Whedon's Commentaries on the Buffy the Vampire Slayer DVDs PDF Version (Acrobat Reader Required) Recommended. Here and in each issue 1 3 of Slayage the editors will recommend 2 [1.2] 4 [1.4] [1.1] [1.3] writing on BtVS available on the Internet. 5 6 [2.2] 7 [2.3] 8 [2.4] [2.1] Robert Hanks, Deconstructing Buffy 11-12 9 10 [3.2] [3.3- [3.1] (from ) 4] Manuel de la Rosa, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, the Girl Power Movement, and 13-14 Heroism 15 [4.3] [4.1- Archives Andy Sawyer, In a Small Town in 2] California . the Subtext is Becoming Text (from ) Anthony Cordesman, Biological Warfare and the "Buffy" Paradigm" Paula Graham, Buffy Wars: The Next file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/David%20Lavery/Lavery%20Documents/SOIJBS/Numbers/slayage6.htm (1 of 2)12/21/2004 4:23:36 AM Slayage, Number 6: Melton J. -

The Postmodern Sacred

The Postmodern Sacred Popular Culture Spirituality in the Genres of Science Fiction, Fantasy and Fantastic Horror Em McAvan BA (Honours) Curtin University This thesis is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Murdoch University, August 2007. Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary educational institution. __________________________ Acknowledgements My thanks to Vijay Mishra and Wendy Parkins for their supervision, my friends and family for their support and encouragement, and to Candy Robinson for everything else. Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One 17 The Postmodern Sacred Chapter Two 60 ‘Something Up There’: Transcendental Gesturing in New Age influenced texts Chapter Three 96 Of Gods and Monsters: Literalising Metaphor in the Postmodern Sacred Chapter Four 140 That Dangerous Supplement: Christianity and the New Age in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings Chapter Five 171 Good, Evil and All That Stuff: Morality and Meta-Narrative in the Postmodern Sacred Chapter Six 214 Nostalgia and the Sacredness of “Real” Experience in Postmodernity Conclusion 253 Bibliography 259 1 Introduction The Return of the Religious and the Postmodern Sacred God is no longer dead. When Nietzsche famously declared his death toward the end of the 19th century, it seemed possible, even inevitable, that God and religion would die under the rationalist atheist onslaught. That, however, was not to be the case. Religion and “spirituality” have survived the atheist challenge, albeit profoundly changed. Although there are a number of contributing factors, the revival of the religious in the West has occurred partly as a result of the postmodernist collapse of the scientific meta-narratives that made atheism so powerful.