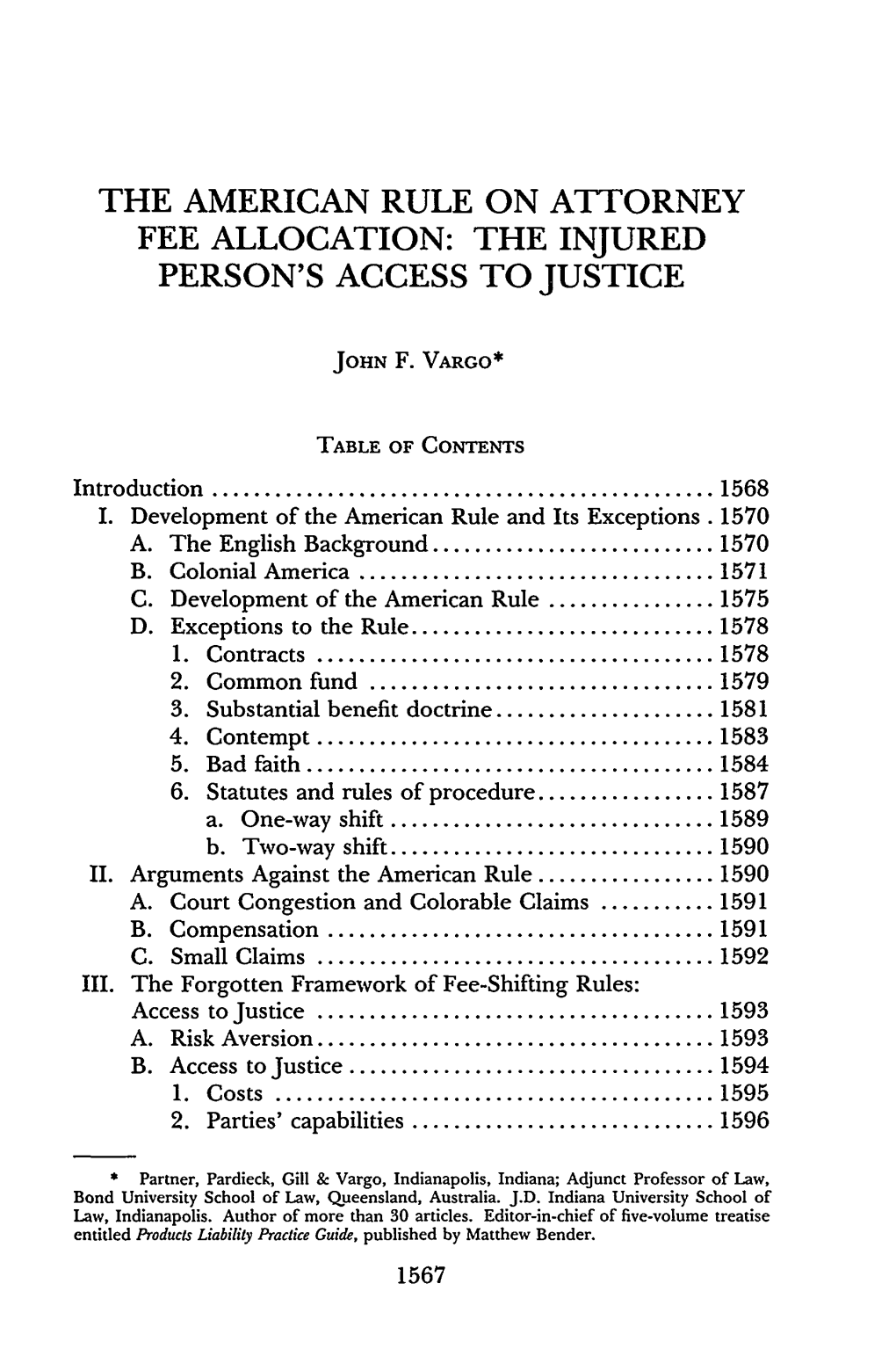

The American Rule on Attorney Fee Allocation: the Injured Person's Access to Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Somaliland: a Model for Greater Liat Krawczyk Somalia?

JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL SERVICE VOLUME 21 | NUMBER 1 | SPRING 2012 i Letter from the Editor Maanasa K. Reddy 1 Women’s Political Participation in Sub- Anna-Kristina Fox Saharan Africa: Producing Policy That Is Important to Women and Gender Parity? 21 Russia and Cultural Production Under Alina Shlyapochnik Consumer Capitalism 35 Somaliland: A Model for Greater Liat Krawczyk Somalia? 51 Regulatory Convergence and North Inu Barbee American Integration: Lessons from the European Single Market 75 Elite Capture or Capturing the Elite? The Ana De Paiva Political Dynamics Behind Community- Driven Development 85 America’s Silent Warfare in Pakistan: An Annie Lynn Janus Analysis of Obama’s Drone Policy 103 Asia as a Law and Development Exception: Does Indonesia Fit the Mold? Jesse Roberts 119 Islamic Roots of Feminism in Egypt and Shreen A. Khan Morocco Knut Fournier Letter from the Editor Maanasa K. Reddy Dear Reader, Many of my predecessors have lamented the Journal’s lack of thematic coherence; I believe that this, the 20th Anniversary, issue has taken a step forward. The first and last articles of the issue discuss gender and feminism, which you may point out isn’t really thematic coherence. This is true; however, I am proud to present a Journal comprised of eight articles, written by eight incredibly talented female authors and one equally talented male co-author on a variety of international service issues. The Journal receives many submissions for every issue with about a 45/55 split from males and females respectively, according to data from the past three years of submissions. The selection process is blind, with respect to identity and gender, and all selections are based on the merits of the writing and relevance of the content. -

“So Counselor, What Are the Chances of Getting My Litigation Fees and Costs Reimbursed from the Trust Or Estate Corpus?” by William M

Trusts “So Counselor, What Are the Chances of Getting My Litigation Fees and Costs Reimbursed from the Trust or Estate Corpus?” by William M. Kelleher and Phillip A. Giordano Gordon, Fournaris & Mammarella, P.A. rust and estate litigants often ask their attorneys whether they will be able to obtain reimbursement of their litigation fees and costs. The short Tanswer is that it depends on the facts, nature, and result of the case. While that is quite true, it is also fair to say that trust and estate litigants generally have a better chance of reimbursement than do litigants in other areas of American litigation.1 The Three General Bases for Reimbursement of Counsel Fees and Costs Out of a Trust The three alternate bases under which litigation fees and costs can be reimbursed from a trust corpus are: (1) Delaware common law, (2) 12 Del. C. § 3584, and (3) the bad faith exception to the American Rule. From the get-go, it is important to know that winning is not a necessary precondition to recovering attorneys’ fees in trust litigation.2 The catch-all Delaware common law basis to award fees in trust litigation If relying on the Delaware common law, the awarding of “fees out of the trust corpus has generally been proper in two circumstances: (i) where the attorney’s services are necessary for the proper administration of the trust, or (ii) where the services otherwise result in a benefit to the trust.”3 20 Delaware Banker - Summer 2017 Section 3584 of Title 12 of the Delaware Code cases, the “exceptional circumstances” could overlap with Turning to the code, 12 Del. -

View Full Article

ARTICLE THE GLOBALIZATION OF ENTREPRENEURIAL LITIGATION: LAW, CULTURE, AND INCENTIVES JOHN C. COFFEE, JR.† INTRODUCTION ............................................................................ 1896 I. THE EUROPEAN FRONT: BARRIERS OUTFLANKED .................. 1900 A. The Fortis Litigation .................................................................. 1902 B. The Volkswagen Litigation .......................................................... 1908 II. ASIA: A SHIFT TOWARDS ENTREPRENEURIAL LITIGATION ...... 1911 A. Japan ....................................................................................... 1912 B. South Korea .............................................................................. 1914 C. China ...................................................................................... 1916 III. IMPLICATIONS AND ANALYSIS .................................................. 1917 A. How Should We Understand This New Phenomenon? ..................... 1917 B. New Patterns and New Issues ..................................................... 1919 1. New Players ...................................................................... 1919 2. The Third Party Funder: Superior or Inferior? .................. 1920 3. Reverse Auctions .............................................................. 1920 4. Unequal Distribution? ....................................................... 1921 5. Will the American Entrepreneurs Fade Away? ................... 1922 6. Counter-Reaction? ........................................................... -

PRESENT: All the Justices THOMAS HUNT ROBERTS OPINION by V

PRESENT: All the Justices THOMAS HUNT ROBERTS OPINION BY v. Record No. 180122 JUSTICE D. ARTHUR KELSEY SEPTEMBER 6, 2018 VIRGINIA STATE BAR FROM THE VIRGINIA STATE BAR DISCIPLINARY BOARD Thomas Hunt Roberts appeals a decision of the Virginia State Bar Disciplinary Board (the “Disciplinary Board” or the “Board”) sanctioning him with a public reprimand with terms after finding that he violated Rules 1.15(a)(3)(ii) and 1.15(b)(5) of the Virginia Rules of Professional Conduct (“Disciplinary Rules”). Finding no error in the Board’s decision, we affirm. I. On appeal, “we view the evidence and all reasonable inferences that may be drawn therefrom in the light most favorable to the Bar, the prevailing party below.” Green v. Virginia State Bar, ex rel. Seventh Dist. Comm., 274 Va. 775, 783 (2007). A. THE REPRESENTATION AGREEMENT In December 2014, Lauren Hayes engaged Thomas H. Roberts & Associates, P.C., to represent her regarding a personal injury claim arising out of a vehicle collision. On behalf of the firm, Roberts entered into a Representation Agreement, see 2 J.A. at 332-37, which, among other things, provided that the firm would receive a contingency fee of “33 1/3 percent of the gross . of any and all judgment and/or recovery, computed before any deductions, including but not limited to expenses or costs,” id. at 332. The agreement stated that the contingency fee would increase to 40% “[i]f the recovery is within 45 days of the first trial date or thereafter.” Id. It also provided that “any settlement or award” that included attorney fees “shall be paid to the law firm in addition to the contingency fees provided for above.” Id. -

Toward a History of the American Rule on Attorney Fee Recovery

TOWARD A HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN RULE ON ATTORNEY FEE RECOVERY JOHN LEUBSDORF* I INTRODUCTION In a sense, the American rule has no history. As far back as one can trace, courts in this country have allowed winning litigants to recover their litigation costs from losers only to the extent prescribed by the legislature.I But closer exam- ination reveals that the justification of this rule and its significance in the economy of litigation have varied over the years. Indeed, there may be too much history to handle: the path leads to the study of aspects of procedure, remedies, and profes- sional responsibility which interact with fee rules, and beyond that into the uncharted finances of the American bar. This terrain is also obscured by the pecu- liar reluctance of the bench and bar either to justify or to change a law of costs which required successful litigants to bear most of the expense of vindicating themselves. This article will sketch the history of attorney fee recovery in the United States. During the late colonial period, legislation provided for fee recovery as an aspect of comprehensive attorney fee regulation. But this regulatory scheme did not long survive the Revolution. During the first half of the nineteenth century, lawyers freed themselves from fee regulation and gained the right to charge clients what the market would bear. As a result, the right to recover attorney fees from ..n opposing party became an unimportant vestige. This triumph of fee contracts between lawyer and client as the financial basis of litigation prepared the way for legislators and judges to proclaim the principle that one party should not be liable for an opponent's legal expenses. -

The Unruly Exclusionary Rule

Marquette Law Review Volume 78 Article 3 Issue 1 Fall 1994 The nrU uly Exclusionary Rule: Heeding Justice Blackmun's Call to Examine the Rule in Light of Changing Judicial Understanding About Its Effects Outside the Courtroom Harry M. Caldwell Carol A. Chase Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Harry M. Caldwell and Carol A. Chase, The Unruly Exclusionary Rule: Heeding Justice Blackmun's Call to Examine the Rule in Light of Changing Judicial Understanding About Its Effects Outside the Courtroom, 78 Marq. L. Rev. 45 (1994). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol78/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNRULY EXCLUSIONARY RULE: HEEDING JUSTICE BLACKMUN'S CALL TO EXAMINE THE RULE IN LIGHT OF, CHANGING JUDICIAL UNDERSTANDING ABOUT ITS EFFECTS OUTSIDE THE COURTROOM HARRY M. CALDWELL* CAROL A. CHASE** I. INTRODUCTION There is a war raging in the hearts and minds of most Americans over the efficacy of the American Criminal Justice system. Americans are concerned with rising crime and they sense that the criminal justice sys- tem is not adequately protecting them from crime or criminals. If pressed to identify a focal point of criticism of the justice system, many would name the Exclusionary Rule. The Rule is popularly believed to exclude even the most damning evidence for the slightest police error. -

Cost and Fee Allocation in Civil Procedure

International Academy of Comparative Law 18th World Congress Washington D.C. July 21-31, 2010 Topic II.C.1 COST AND FEE ALLOCATION IN CIVIL PROCEDURE General Reporter: Mathias Reimann University of Michigan Introduction The following questionnaire is intended to cover civil procedure only, i.e., cases brought under private and commercial law. It does not intend to address criminal, constitutional, administrative proceedings, and arbitration. It consists of 25 questions organized under seven main headings. In answering them, please distinguish, as far as appropriate, what is usual, what is unusual but permitted, and what it prohibited. If there are readily available statistics, please provide them (in an appendix or otherwise). Please strive to be clear and concise and stay as close to the substance and sequence of the questions as possible so as to ensure the comparability of answers across a large number of countries. If a question does not make sense in the context of your legal system, briefly say so; if other issues are pertinent, please mention them. Questionnaire I. The Basic Rules: Who Pays? 1. What is the basic rule of cost and fee allocation - that each party bears its own or that the loser pays all? Are attorneys' fees and court costs treated differently? What is the principal justification for this rule? The cost of litigation consists of court fee (saiban hiyo)and party fee(tojisya hiyo). The court fee consists of payment to the court for sue and the cost of taking of the evidence. The party fee consists of traveling and necessary cost of party and representative. -

Cost and Fee Allocation in Civil Procedure James Maxeiner University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected]

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 2010 Cost and Fee Allocation in Civil Procedure James Maxeiner University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Courts Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Cost and Fee Allocation in Civil Procedure, 58 Am. J. Comp. L. 195 (2010) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JAMES R. MAXEINER* Cost and Fee Allocation in Civil Proceduret Court costs in American civil procedure are allocated to the loser ("loser pays") as elsewhere in the civilized world. As Theodor Sedgwick, America's first expert on damages opined, it is matter of inherent justice that the party found in the wrong should indemnify the party in the right for the expenses of litigation. Yet attorneys' fees are not allocated this way in the United States: they are allowed to fall on the party that incurs them (the ''American rule," better, the Ameri can practice). According to Albert Ehrenzweig, Austrian judge, emigre and then prominent American law professor, the American practice is "a festering cancer in the body of our law." This Article surveys Ameri can cost and fee allocation practices. The author hopes that the Article will serve as a prolegomenon from an American perspective for more encompassing comparative studies, including eventually of empirical studies. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King’S Research Portal At

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Judicial Strategy in Insurgencies Ledwidge, Frank Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 23. Sep. 2021 Judicial Strategy in Insurgencies By Francis Andrew Ledwidge A Thesis Submitted for examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Kings College London January 2015 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement 1 Abstract This thesis is concerned primarily with the use of law and courts as strategic assets in insurgency. -

ARE Patent Law Alert: the US Supreme Court Holds That the USPTO Cannot Be Reimbursed for Salaries of Its Legal Personnel in Appeals Under § 145 of the Patent Act

ARE Patent Law Alert: The US Supreme Court Holds that the USPTO Cannot Be Reimbursed for Salaries of Its Legal Personnel in Appeals Under § 145 of the Patent Act Author(s): Anthony F. Lo Cicero, Charles R. Macedo, David P. Goldberg, Chandler Sturm Supreme Court of the United States unanimously held in Peter v. NantKwest, Inc. that the term “expenses” in 35 U.S.C. § 145 does not include attorney’s fees, and that the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) cannot recover the salaries of its attorneys and paralegals in appeals brought under that section of the Patent Act. 589 U.S. ___, slip op. (2019). As background, an adverse decision of the USPTO may be challenged via mutually exclusive pathways created by the Patent Act. “Unlike § 141, § 145 permits the application to present new evidence…not presented to the PTO.’” NantKwest, 589 U.S., at ___ (slip op. at 2). A challenge pursuant to § 145 may result in a drawn-out litigation, as there is no limit on an applicant’s ability to introduce new evidence. Thus, the Patent Act “requires applicants who avail themselves of §145 to pay ‘[a]ll the expenses of the proceedings.’” Id. Today’s ruling clarifies that the phrase “[a]ll expenses” does not mean that parties appealing patent rulings under this provision must also pay pro-rata portions of the salaries of the USPTO attorneys and paralegals involved in such appeals. Accordingly, such appeals will now be considerably more affordable. The American Rule Applies to All Statutes When considering the award of attorney’s fees, a fundamental principle, known as the “American Rule,” states that “each litigant pays his own attorney’s fees, win or lose, unless a statute or contract provides otherwise.” Id. -

The Uniform Residential Landlord and Tenant Act and Its Potential Effects Upon Maryland Landlord- Tenant Law

University of Baltimore Law Review Volume 5 Article 5 Issue 2 Spring 1976 1976 The niU form Residential Landlord and Tenant Act and Its Potential Effects upon Maryland Landlord- Tenant Law Steven G. Davison University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Davison, Steven G. (1976) "The niU form Residential Landlord and Tenant Act and Its Potential Effects upon Maryland Landlord- Tenant Law," University of Baltimore Law Review: Vol. 5: Iss. 2, Article 5. Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr/vol5/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Baltimore Law Review by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNIFORM RESIDENTIAL LANDLORD AND TENANT ACT AND ITS POTENTIAL EFFECTS UPON MARYLAND LANDLORD- TENANT LAW Steven G. Davisont The author examines the Uniform Residential Landlord and Tenant Act, which is currently being considered for adoption by the Maryland General Assembly. The Act codifies the recent judicial tendency to treat the landlord-tenant relationship as one governed by contract principles rather than by the principles governing the conveyance of estates in land. The article's major emphasis is on the potential impact of the Act on the common law and the present Maryland statutes governing the landlord-tenantrelationship. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction II. -

In the Supreme Court of the United States ______

NO. 18-801 In the Supreme Court of the United States ________________ LAURA PETER, DEPUTY DIRECTOR, UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE, PETITIONER, v. NANTKWEST, INC., RESPONDENT. ________________ ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT EN BANC ________________ BRIEF OF THE INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW ASSOCIATION OF CHICAGO AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENT NANTKWEST, INC. ___________________________________________ MARGARET M. DUNCAN Of Counsel: Counsel of Record CHARLES W. SHIFLEY MCDERMOTT WILL & EMERY PRESIDENT LLP THE INTELLECTUAL 444 W. Lake Street PROPERTY LAW Suite 4000 ASSOCIATION OF CHICAGO Chicago, IL 60606 P.O. BOX 472 (312) 372-2000 CHICAGO, IL 60690 Of Counsel: ROBERT RESIS DAVID MLAVER BANNER & WITCOFF, LTD. MCDERMOTT WILL & EMERY LLP 71 S. Wacker Dr., Suite 500 North Capitol St. NW 3600 Washington, DC 20001 Chicago, IL 60606 (202) 756-8000 (312) 463-5000 Counsel for Amicus Curiae The Intellectual Property Law Association of Chicago July 22, 2019 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ...................................... iii STATEMENT OF INTEREST .................................... 1 ISSUE PRESENTED .................................................. 3 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..................................... 4 ARGUMENT ............................................................... 6 I. THE AMERICAN RULE IS A BEDROCK PRINCIPLE OF AMERICAN JURISPRUDENCE WITH GENERAL APPLICATION ...................................................... 6 II. THE FOURTH CIRCUIT