Ashes to Ashes As Postfeminist Recession Television Hannah Hamad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Crime Drop and the Security Hypothesis

British Society of Criminology Newsletter, No. 64, Special Edition, Autumn 2009 Life on Mars Eugene McLaughlin City University, London Titles of annual academic conferences are intriguing matters. The title of the BSC Cardiff Conference was “A „Mirror‟ or a „Motor‟? What is Criminology for?”. Prospective delegates were asked to deliberate on how they viewed themselves and their work. Should they be providing a „mirror‟ that „seeks to reflect as accurately as possible the conditions that are encountered in the contemporary social order?‟. Or should they have an applied orientation with their research being „a „motor‟ of social change to advance key values of justice and security?‟. Now of course the „either/or‟ nature of the quotes are worthy of a paper in themselves and a plenary session addressing the „what is criminology for?‟ theme directly would have been fascinating. As with every conference, the initial session reflected the organisers‟ struggle to manage the array of interests that define British criminology. The opening of the conference runs to familiar formula of a brief welcome by the President and someone representing the place hosting the event. There would also be an opening plenary paper by an eminent criminologist tasked to, in some way, capture the theme of the conference. In this case it would be Lawrence Sherman seeking to evidence the enlightenment credentials of „Experimental Criminology‟. However, this year‟s opening would also include the BSC‟s new Outstanding Achievement Award. Eventual confirmation that Stan Cohen would be the recipient of the first award added an extra buzz to proceedings. After all, it was Cohen who has described his ambivalent but ongoing relationship with criminology as one of “repressive tolerance”. -

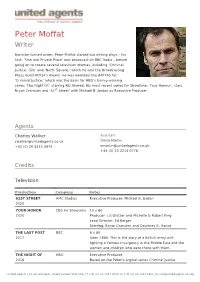

Peter Moffat Writer

Peter Moffat Writer Barrister turned writer, Peter Moffat started out writing plays – his first, ‘Fine and Private Place’ was broadcast on BBC Radio – before going on to create several television dramas, including ‘Criminal Justice, ‘Silk’ and ‘North Square,’ which he won the Broadcasting Press Guild Writer’s Award. He was awarded two BAFTAS for ‘Criminal Justice,’ which was the basis for HBO’s Emmy-winning series ‘The Night Of,’ starring Riz Ahmed. His most recent series for Showtime, ‘Your Honour,’ stars Bryan Cranston and ‘61st Street’ with Michael B. Jordan as Executive Producer. Agents Charles Walker Assistant [email protected] Olivia Martin +44 (0) 20 3214 0874 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0778 Credits Television Production Company Notes 61ST STREET AMC Studios Executive Producer: Michael B. Jordan 2020 YOUR HONOR CBS for Showtime 10 x 60 2020 Producer: Liz Glotzer and Michelle & Robert King Lead Director: Ed Berger Starring: Bryan Cranston and Courtney B. Vance THE LAST POST BBC 6 x 60 2017 Aden 1965. This is the story of a British army unit fighting a Yemeni insurgency in the Middle East and the women and children who were there with them. THE NIGHT OF HBO Executive Producer 2016 Based on the Peter's orginal series Criminal Justice United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes UNDERCOVER BBC1 6 x60' with Sophie Okonedo and Adrian Lester, Denis 2015 Haysbert Director James Hawes, Exec Producer Peter Moffat THE VILLAGE series Company Pictures 6 x 60' with John Simm, Maxine Peake, Juliet Stevenson 1 / BBC1 Producer: Emma Burge; Director: Antonia Bird 2013 SILK 2 BBC1 6 x 60' With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Frances 2012 Barber, and Neil Stuke Producer: Richard Stokes; Directors: Alice Troughton, Jeremy Webb, Peter Hoar SILK BBC1 6 x 60' 2011 With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Natalie Dormer, Tom Hughes and Neil Stuke. -

Oxford Lecture 1 - Final Master

OXFORD LECTURE 1 - FINAL MASTER HOW TO GROW A CREATIVE BUSINESS BY ACCIDENT The legendarily bullish film director Alan Parker once adapted Shaw's famous dictum about the academic profession - "those who can, do. Those who can't teach." So far so familiar. And to many in this room, no doubt, so annoying. But he went on: "those who can't teach, teach gym. And those who can't teach gym, teach at film school." I appreciate that Oxford is not a film school, though it has a more distinguished record than any film school for supplying the talent that has fuelled the British film and TV industries for almost a century - on and off camera. Writers like Richard Curtis, who brought us 4 Weddings and a Funeral, Love Actually, The Vicar of Dibley and Blackadder; or The Full Monty and Slumdog Millionaire scribe Simon Beaufoy; directors of the diversity of Looking for Eric's Ken Loach and 24 Hour Party People's Michael Winterbottom; writer/directors like Monty Python's Terry Jones and the Thick of It's Armando Iannucci; actors and performers ranging from Hugh Grant to Rowan Atkinson; and broadcasting luminaries like the BBC's Director General Mark Thompson and News International's very own Rupert Murdoch. So, Oxford has been a pretty efficient film and TV school, without even trying. And perhaps that is Parker's point. Can what passes for creativity in film and TV ever really be taught? But here in my capacity as News International Visiting Professor of Broadcast Media (or if you prefer an acronym, NIVPOB - the final M is silent) I may be even further down Parker's food chain. -

Ebook Download Ashes to Ashes Ebook Free Download

ASHES TO ASHES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tami Hoag | 593 pages | 01 Aug 2000 | Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc | 9780553579604 | English | New York, United States Ashes to Ashes PDF Book Greil Marcus. Save Word. This site uses cookies and other tracking technologies to assist with navigation and your ability to provide feedback, analyse your use of our products and services, assist with our promotional and marketing efforts, and provide content from third parties. Ashes to ashes , funk to funky. See how we rate. Hunt's grass 'Rock Salmon' Doyle is murdered after divulging an upcoming heist, which Alex Steve Silberman and David Shenk. Share reduce something to ashes Post the Definition of reduce something to ashes to Facebook Share the Definition of reduce something to ashes on Twitter. User Reviews. The exploits of Gene Hunt continue in the hit drama series. Gene distrusts two former colleagues claiming to have travelled from Manchester on the hunt for an aged stand-up comedian who has allegedly stolen cash from the Police Widows' Fund. I hope that we find out a lot more about this compelling character in the future. Muse, Odalisque, Handmaiden. While the hard science of memorial diamonds is fascinating—a billion years in a matter of weeks! Creators: Matthew Graham , Ashley Pharoah. Queen: The Complete Works. When a violent burglary occurs at Alex's in-laws' house, she encounters their year-old son Peter - the future father of Molly. Learn More about reduce something to ashes Share reduce something to ashes Post the Definition of reduce something to ashes to Facebook Share the Definition of reduce something to ashes on Twitter Dictionary Entries near reduce something to ashes reducer sleeve reduce someone to silence reduce someone to tears reduce something to ashes reducible polynomial reducing agent reducing coupling. -

Keeley Hawes, Philip Glenister, Dean Andrews, Marshall Lancaster, Montserrat Lombard

Ashes to Ashes (DVD) Talent: Keeley Hawes, Philip Glenister, Dean Andrews, Marshall Lancaster, Montserrat Lombard. Director: Johnny Campbell, Bille Eltringham Classification: M (Mature) Duration: 516 minutes (including 8 episodes) We rate it: Five stars. Date of review: 22nd October, 2009 Several years ago, audiences in both the UK and Australia were introduced to the wondrous BBC drama Life on Mars. Taking its name from a David Bowie song, Life on Mars followed the intriguing exploits of a 2006 Manchester cop, Sam Tyler, (played by the wonderful John Simm) who was hit by a car and seemingly sent back in time to 1973. The show functioned as a compelling psychological thriller, following Tyler’s efforts to discover what had sent him back in time (was he in a coma, dying, dreaming, or in some kind of limbo-land or Purgatory?) and his attempts to escape 1973 and get back to his life in 2006. At the same time, the show was a loving and at times hilarious re-creation of the 1970s British cop-show milieu (think of The Sweeney crossed with The Professionals, but shot with today’s filmmaking technology), and it featured the wonderful Philip Glenister as the now-iconic DCI Gene Hunt, a politically- incorrect, hilariously foul-mouthed and utterly lovable character who infuriated Tyler as often as he helped him in his various quests. Life on Mars was a critical and commercial hit, and it spawned a tremendously effective second series. The characters central to Life on Mars were both sympathetic and fascinating, the writing and direction of the episodes occasionally awe-inspiring, and the mystery at the heart of the entire show was brilliantly handled to the very end. -

A Review of New Historical Drama from the BBC

Eras Edition 9, November 2007 – http://www.arts.monash.edu.au/eras ‘Time-warp Television’ – A review of new historical drama from the BBC: Life on Mars, created by Mathew Graham, Tony Jordan and Ashley Pharoah, BBC, 2006. Robin Hood, created by Foz Allan and Dominic Minghella, BBC, 2006. Torchwood, created by Russell T. Davies, BBC, 2006. Robin Hood in an anorak and touting an anti-war message? Costume drama in the gritty back streets of 1970s Manchester? Clearly this is not your father’s BBC. While there is still plenty of Austen and Dickens for the purist, the BBC, long the home of waistcoats, mutton chops and empire waists, has breathed some new life into the historical drama with two series that seem to engage as much with the way we respond to history as to the historical setting itself. A cult and critical hit, Life on Mars, follows Manchester Police Detective Sam Tyler (played by John Simm) who is ‘transported’ back to 1973 after being hit by a car. Used to being a Detective Chief Inspector with expensive digs, a well-cut suit, and police-work governed by political correctness and computers, Sam finds himself demoted, dressed in a leather jacket, living in a dingy room with a Murphy-bed, and working with DCI Gene Hunt. Hunt, played with joyful relish by Philip Glenister, is the very antithesis of modern policing. He is unabashedly racist, sexist, homophobic and not above bashing the uncooperative suspect mid-interview. All guts and reaction, he is the ying to Sam’s yang, as it becomes clear that DI Tyler has lost the ability to trust his instincts. -

Fantastika Journal

FANTASTIKAJOURNAL After Bowie: Apocalypse, Television and Worlds to Come Andrew Tate Volume 4 Issue 1 - After Fantastika Stable URL: https:/ /fantastikajournal.com/volume-4-issue-1 ISSN: 2514-8915 This issue is published by Fantastika Journal. Website registered in Edmonton, AB, Canada. All our articles are Open Access and free to access immediately from the date of publication. We do not charge our authors any fees for publication or processing, nor do we charge readers to download articles. Fantastika Journal operates under the Creative Commons Licence CC-BY-NC. This allows for the reproduction of articles for non-commercial uses, free of charge, only with the appropriate citation information. All rights belong to the author. Please direct any publication queries to [email protected] www.fantastikajournal.com Fantastika Journal • Volume 4 • Issue 1 • July 2020 AFTER BOWIE: APOCALYPSE, TELEVISION AND WORLDS TO COME Andrew Tate Let’s start with an image or, more accurately, an image of images from a 1976 film. A character called Thomas Jerome Newton is surrounded by the dazzle and blaze of a bank of television screens. He looks vulnerable, overwhelmed and enigmatic. The moment is an oddly perfect metonym of its age, one that speaks uncannily of commercial confusion, artistic innovation and political inertia. The film is Nic Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth – an adaptation of Walter Tevis’ 1963 novel – and the actor on screen is David Bowie, already celebrated for his multiple, mutable pop star identities in his first leading role in a motion picture. In an echo of what Nicholas Pegg has called “the ongoing sci-fi shtick that infuses his most celebrated characters” – including by this time, for example, Major Tom of “Space Oddity” (1969), rock star messiah Ziggy Stardust and the post-apocalyptic protagonists of “Drive-In Saturday” (1972) – he performs the role of an alien (Kindle edition, location 155). -

A2A 3 Ep 8 Shooting Script

1 EXT. PLAYING FIELDS - DAY 0 1 Municipal parkland. * STEWART HALL (V.O.) It was Will Shakespeare who wrote; “We must take the current when it serves or lose our ventures.” You join us here at Fenchurch East Recreation Grounds. The current serves. The venture can not be lost. And - IT’S - A - KNOCKOUT!! Iconic Theme Tune kicks in - A giant FOAM-HEADED ALEX DRAKE sets off across the obstacle course, weaving left and right. STEWART HALL commentates between bouts of laughter. A whistle blows. STEWART HALL (V.O.) (CONT’D) And Alex is off! Hither and yon! Camera WHIP PANS to the other end of the field where MOLLY waits in her school uniform, hollering her support. MOLLY Come on mum! You can do it! Back to FOAM-HEAD ALEX who reaches a huge mountain of paper. STEWART HALL (V.O.) Through the paperwork ... And she’s found something! It’s the numbers 6 - 6 - 20 ... A second whistle blows. STEWART HALL (V.O.) (CONT’D) And that’s the cue for DCI Gene Hunt to go after her! A FOAM-HEAD GENE sets off in wobbly pursuit, closing the gap fast. FOAM-HEAD ALEX stumbles. STEWART HALL (V.O.) (CONT’D) He’s gaining! Gene Hunt is gaining! FOAM-HEAD ALEX is reaching a fence with a weather-vane. Familiar to us - the old man with the knapsack. STEWART HALL (V.O.) (CONT’D) Now she has to get around the weather-vane ... FOAM-HEAD ALEX crashes through the fence. STEWART hoots. (CONTINUED) Ashes 3 - Episode 8 - SHOOTING SCRIPT - 18/12/09 2. -

CAST BIOS TOM RILEY (Leonardo Da Vinci) Tom Has Been Seen in A

CAST BIOS TOM RILEY (Leonardo da Vinci) Tom has been seen in a variety of TV roles, recently portraying Dr. Laurence Shepherd opposite James Nesbitt and Sarah Parish in ITV1’s critically acclaimed six-part medical drama series “Monroe.” Tom has completed filming the highly anticipated second season which premiered autumn 2012. In 2010, Tom played the role of Gavin Sorensen in the ITV thriller “Bouquet of Barbed Wire,” and was also cast in the role of Mr. Wickham in the ITV four-part series “Lost in Austen,” alongside Hugh Bonneville and Gemma Arterton. Other television appearances include his roles in Agatha Christie’s “Poirot: Appointment with Death” as Raymond Boynton, as Philip Horton in “Inspector Lewis: And the Moonbeams Kiss the Sea” and as Dr. James Walton in an episode of the BBC series “Casualty 1906,” a role that he later reprised in “Casualty 1907.” Among his film credits, Tom played the leading roles of Freddie Butler in the Irish film Happy Ever Afters, and the role of Joe Clarke in Stephen Surjik’s British Comedy, I Want Candy. Tom has also been seen as Romeo in St Trinian’s 2: The Legend of Fritton’s Gold alongside Colin Firth and Rupert Everett and as the lead role in Santiago Amigorena’s A Few Days in September. Tom’s significant theater experiences originate from numerous productions at the Royal Court Theatre, including “Paradise Regained,” “The Vertical Hour,” “Posh,” “Censorship,” “Victory,” “The Entertainer” and “The Woman Before.” Tom has also appeared on stage in the Donmar Warehouse theatre’s production of “A House Not Meant to Stand” and in the Riverside Studios’ 2010 production of “Hurts Given and Received” by Howard Barker, for which Tom received outstanding reviews and a nomination for best performance in the new Off West End Theatre Awards. -

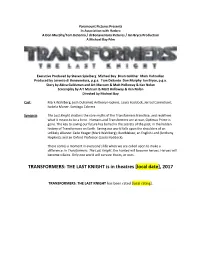

Transformers Franchise, and Redefines What It Means to Be a Hero

Paramount Pictures Presents In Association with Hasbro A Don Murphy/Tom DeSanto / di Bonaventura Pictures / Ian Bryce Production A Michael Bay Film Executive Produced by Steven Spielberg Michael Bay Brian Goldner Mark Vahradian Produced by Lorenzo di Bonaventura, p.g.a. Tom DeSanto Don Murphy Ian Bryce, p.g.a. Story by Akiva Goldsman and Art Marcum & Matt Holloway & Ken Nolan Screenplay by Art Marcum & Matt Holloway & Ken Nolan Directed by Michael Bay Cast: Mark Wahlberg, Josh Duhamel, Anthony Hopkins, Laura Haddock, Jerrod Carmichael, Isabela Moner, Santiago Cabrera Synopsis: The Last Knight shatters the core myths of the Transformers franchise, and redefines what it means to be a hero. Humans and Transformers are at war, Optimus Prime is gone. The key to saving our future lies buried in the secrets of the past, in the hidden history of Transformers on Earth. Saving our world falls upon the shoulders of an unlikely alliance: Cade Yeager (Mark Wahlberg); Bumblebee; an English Lord (Anthony Hopkins); and an Oxford Professor (Laura Haddock). There comes a moment in everyone’s life when we are called upon to make a difference. In Transformers: The Last Knight, the hunted will become heroes. Heroes will become villains. Only one world will survive: theirs, or ours. TRANSFORMERS: THE LAST KNIGHT is in theatres [local date], 2017 TRANSFORMERS: THE LAST KNIGHT has been rated [local rating]. ABOUT THE CAST MARK WAHLBERG (“Cade Yeager”) earned both Academy Award® and Golden Globe® nominations for his standout work in the family boxing film The Fighter and Martin Scorsese’s acclaimed drama The Departed. -

Life on Mars

Appendix 2 Life on Mars 722 Life on Mars Translation strategies Loan Official translation Calque Hypernym Hyponym Explicitation Substitution Lexical recreation Compensation Elimination Creative addition 723 LIFE ON MARS Season 1 Episode 1 (Pilot) 1/1 ORIGINAL FILM DIALOGUE 13.47-13.53 SAM: Who the hell are you? GENE: Gene Hunt, your DCI, and it's 1973. Almost dinner time. I'm 'avin' 'oops. ITALIAN ADAPTATION BACK-TRANSLATION SAM: Chi sei tu? SAM: Who are you? GENE: Gene Hunt, il tuo ispettore capo. E’ GENE: Gene Hunt, your chief inspector. il 1973, ora di cena. E muoio dalla fame. It’s 1973, dinner time. And I’m starving. 1/2 ORIGINAL FILM DIALOGUE 14.21-14.33 OPERATOR: Operator. SAM: No, I want a mobile number. OPERATOR: What? SAM: A mobile number. 0770 813- OPERATOR: Is that an international number? SAM: No, it… I....I need you to connect me to a Virgin... number. Virgin mobile. OPERATOR: Don't you start that sexy business with me, young man. I can trace this call. ITALIAN ADAPTATION BACK-TRANSLATION CENTRALINISTA: Centralino. OPERATOR: Operator. SAM: Senta. Vorrei il numero di un SAM: Listen. I would like to have the cellulare. number of a mobile. CENTRALINO: Cosa? OPERATOR: What? SAM: Il numero di un cellulare. 0770 813… SAM: The number of a mobile. 0770 813… CENTRALINO: E’ un numero OPERATOR: Is it an international number internazionale forse? perhaps? SAM: No. Io ho bisogno che lei mi metta in SAM: No. I need you to connect me to a contatto con un numero di… un cellulare, mobile… number, a mobile phone. -

Weekly Highlights Week 05/06: Sat 6Th - Fri 12Th February 2021

Weekly Highlights Week 05/06: Sat 6th - Fri 12th February 2021 Six Nations Live Saturday, from 1.30pm This year’s tournament begins. This information is embargoed from reproduction in the public domain until Tue 2nd February 2021. Press contacts Further programme publicity information: ITV Press Office [email protected] www.itv.com/presscentre @itvpresscentre ITV Pictures [email protected] www.itv.com/presscentre/itvpictures ITV Billings [email protected] www.ebs.tv This information is produced by EBS New Media Ltd on behalf of ITV +44 (0)1462 895 999 Please note that all information is embargoed from reproduction in the public domain as stated. Weekly highlights Six Nations: Italy v France Live Saturday, 1.30pm 6th February ITV Jill Douglas is joined by Maggie Alphonsi and Gareth Thomas for the first match of the 2021 Guinness Six Nations Championship at the Stadio Olimpico in Rome. France’s exciting young team were a very close second to England in last year’s championship and are highly fancied to win this year’s edition. On the other hand, Italy are hoping to finally end their long wait for a win in the annual tournament. Six Nations: England v Scotland Live Saturday, 4.15pm 6th February ITV Mark Pougatch is at Twickenham as England and Scotland begin their Six Nations Championship, going head to head in a battle to win the famous Calcutta Cup. Eddie Jones’s champions England are on a rich run of form having won their last eight matches, sealing the Six Nations title and the Autumn Nations Cup along the way.