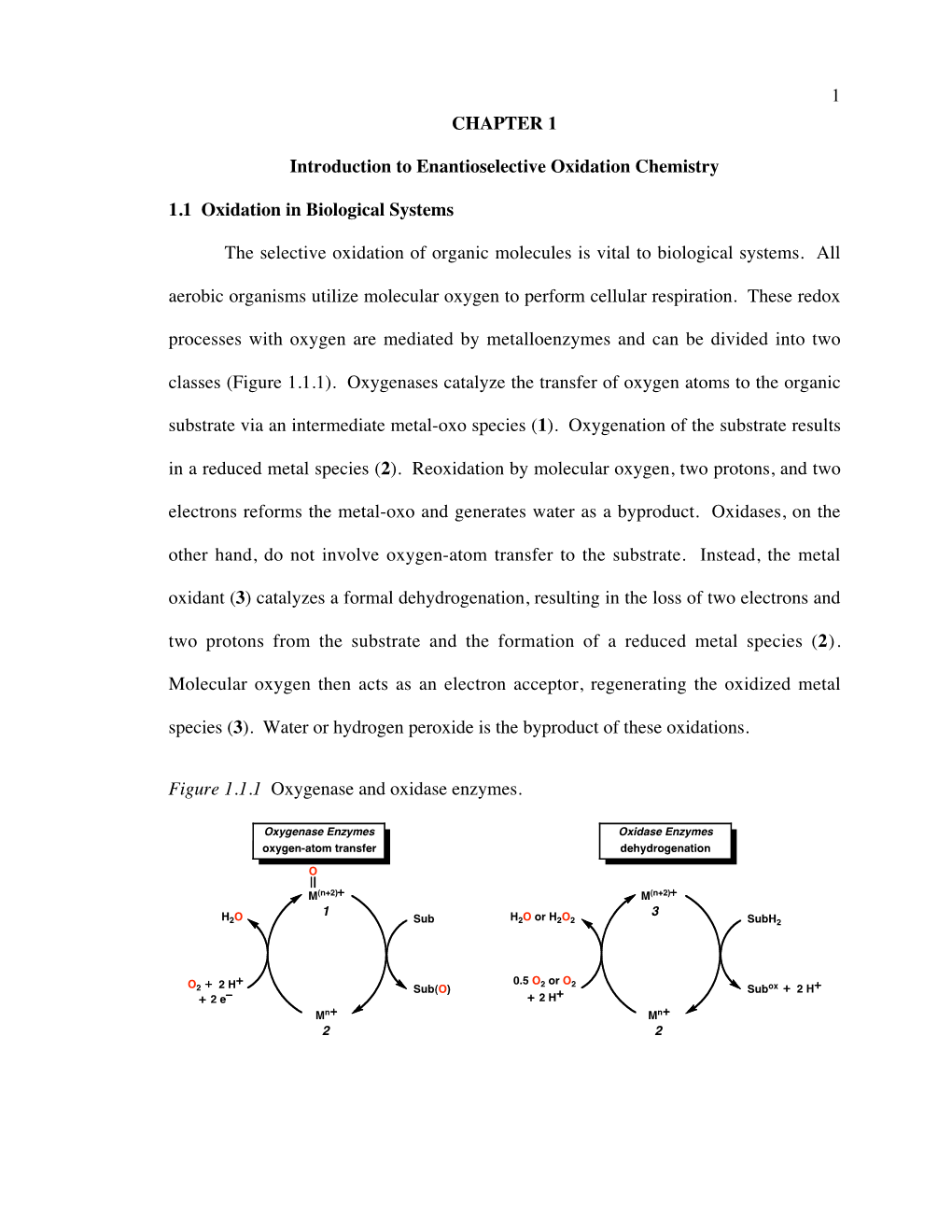

1 CHAPTER 1 Introduction to Enantioselective Oxidation Chemistry 1.1 Oxidation in Biological Systems the Selective Oxidation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Improved Catalytic Performance of Carrier-Free Immobilized Lipase by Advanced Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates Technology

Improved Catalytic Performance of Carrier-Free Immobilized Lipase by Advanced Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates Technology Xia Jiaojiao Jiangsu University of Science and Technology: Jiangsu University Yan Yan Jiangsu University Bin Zou ( [email protected] ) Jiangsu University https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3816-8776 Adesanya Idowu Onyinye Jiangsu University Research Article Keywords: lipase, carrier-free, immobilization, ionic liquid, stability Posted Date: May 24th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-505612/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/20 Abstract The cross-linked enzyme aggregates (CLEAs) are one of the technologies that quickly immobilize the enzyme without a carrier. This carrier-free immobilization method has the advantages of simple operation, high reusability and low cost. In this study, ionic liquid with amino group (1-aminopropyl-3- methylimidazole bromideIL) was used as the novel functional surface molecule to modify industrialized lipase (Candida rugosa lipase, CRL). The enzymatic properties of the prepared CRL-FIL-CLEAs were investigated. The activity of CRL-FIL-CLEAs (5.51 U/mg protein) was 1.9 times higher than that of CRL- CLEAs without surface modication (2.86 U/mg protein). After incubation at 60℃ for 50 min, CRL-FIL- CLEAs still maintained 61% of its initial activity, while the value for CRL-CLEAs was only 22%. After repeated use for ve times, compared with the 22% residual activity of CRL-CLEAs, the value of CRL-FIL- CLEAs was 51%. Further kinetic analysis indicated that the Km values for CRL-FIL-CLEAs and CRL-CLEAs were 4.80 mM and 8.06 mM, respectively, which was inferred that the anity to substrate was increased after modication. -

– with Novozymes Enzymes for Biocatalysis

Biocatalysis Pregabalin case study Smarter chemical synthesis – with Novozymes enzymes for biocatalysis The new biocatalytic route results in process improvements, reduced organic solvent usage and substantial reduction of waste streams in Pregabalin production. Introduction Biocatalysis is the application of enzymes to replace chemical Using Lipolase®, a commercially available lipase, rac-2- catalysts in synthetic processes. In recent past, the use of carboxyethyl-3-cyano-5-methylhexanoic acid ethyl ester biocatalysis has gained momentum in the chemical and (1) can be resolved to form (S)-2-carboxyethyl-3-cyano-5- pharmaceutical industries. Today, it’s an important tool for methylhexanoic acid (2). Compared to the first-generation medicinal, process and polymer chemists to develop efficient process, this new route substantially improves process and highly attractive organic synthetic processes on an efficiency by setting the stereocenter early in the synthesis and industrial scale. enabling the facile racemization and reuse of (R)-1. The biocatalytic process for Pregabalin has been developed It outperforms the first-generation manufacturing process also by Pfizer to boost efficiency in Pregabalin production using by delivering higher yields of Pregabalin and by resulting in Novozymes Lipolase®. substantial reductions of waste streams, corresponding to a 5-fold decrease in the E-Factor from 86 to 17. Development of the biocatalytic process for Pregabalin involves four stages: • Screening to identify a suitable enzyme • Performing optimization of the enzymatic reaction to optimize throughput and reduce enzyme loading • Exploring a chemical pathway to preserve the enantiopurity of the material already obtained and lead to Pregabalin, and • Developing a procedure for the racemization of (R)-1 Process improvements thanks to the biocatalytic route Pregabalin chemical synthesis H Knovenagel CN condensation cyanation KOH 0 Et02C CO2Et Et02C CO2Et Et02C CO2Et CNDE (1) CN NH2 1. -

Separation of the Mixtures of Chiral Compounds by Crystallization

1 Separation of the Mixtures of Chiral Compounds by Crystallization Emese Pálovics2, Ferenc Faigl1,2 and Elemér Fogassy1* 1Department of Organic Chemistry and Technology, Budapest University of Technology and Economics, 2Research Group for Organic Chemical Technology, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest, Hungary 1. Introduction Reaction of a racemic acid or base with an optically active base or acid gives a pair of diastereomeric salts. Members of this pair exhibit different physicochemical properties (e.g., solubility, melting point, boiling point, adsorbtion, phase distribution) and can be separated owing to these differences. The most important method for the separation of enantiomers is the crystallization. This is the subject of this chapter. Preparation of enantiopure (ee~100%) compounds is one of the most important aims both for industrial practice and research. Actually, the resolution of racemic compounds (1:1 mixture of molecules having mirror-imagine relationship) still remains the most common method for producing pure enantiomers on a large scale. In these cases the enantiomeric mixtures or a sort of their derivatives are separated directly. This separation is based on the fact that the enantiomeric ratio in the crystallized phase differs from the initial composition. In this way, obtaining pure enantiomers requires one or more recrystallizations. (Figure 1). The results of these crystallizations (recrystallizations) of mixtures of chiral compounds differ from those observed at the achiral compounds. Expectedly, not only the stereoisomer in excess can be crystallized, because the mixture of enantiomers (with mirror image relationship) follows the regularities established from binary melting point phase diagrams, and ternary composition solubility diagrams, respectively, as a function of the starting enantiomer proportion. -

A Reminder… Chirality: a Type of Stereoisomerism

A Reminder… Same molecular formula, isomers but not identical. constitutional isomers stereoisomers Different in the way their Same connectivity, but different atoms are connected. spatial arrangement. and trans-2-butene cis-2-butene are stereoisomers. Chirality: A Type of Stereoisomerism Any object that cannot be superimposed on its mirror image is chiral. Any object that can be superimposed on its mirror image is achiral. Chirality: A Type of Stereoisomerism Molecules can also be chiral or achiral. How do we know which? Example #1: Is this molecule chiral? 1. If a molecule can be superimposed on its mirror image, it is achiral. achiral. Mirror Plane of Symmetry = Achiral Example #1: Is this molecule chiral? 2. If you can find a mirror plane of symmetry in the molecule, in any achiral. conformation, it is achiral. Can subject unstable conformations to this test. ≡ achiral. Finding Chirality in Molecules Example #2: Is this molecule chiral? 1. If a molecule cannot be superimposed on its mirror image, it is chiral. chiral. The mirror image of a chiral molecule is called its enantiomer. Finding Chirality in Molecules Example #2: Is this molecule chiral? 2. If you cannot find a mirror plane of symmetry in the molecule, in any conformation, it is chiral. chiral. (Or maybe you haven’t looked hard enough.) Pharmacology of Enantiomers (+)-esomeprazole (-)-esomeprazole proton pump inhibitor inactive Prilosec: Mixture of both enantiomers. Patent to AstraZeneca expired 2002. Nexium: (+) enantiomer only. Process patent coverage to 2007. More examples at http://z.umn.edu/2301drugs. (+)-ibuprofen (-)-ibuprofen (+)-carvone (-)-carvone analgesic inactive (but is converted to spearmint oil caraway oil + enantiomer by an enzyme) Each enantiomer is recognized Advil (Wyeth) is a mixture of both enantiomers. -

II. Stereochemistry 5

B.Sc.(H) Chemistry Semester - II Core Course - III (CC-III) Organic Chemistry - I II. Stereochemistry 5. Physical and Chemical Properties of Stereoisomers Dr. Rajeev Ranjan University Department of Chemistry Dr. Shyama Prasad Mukherjee University, Ranchi 1 Syllabus & Coverage Syllabus II Stereochemistry: Fischer Projection, Newmann and Sawhorse Projection formulae and their interconversions. Geometrical isomerism: cis–trans and syn-anti isomerism, E/Z notations with Cahn Ingold and Prelog (CIP) rules for determining absolute configuration. Optical Isomerism: Optical Activity, Specific Rotation, Chirality/Asymmetry, Enantiomers, Molecules with two or more chiral-centres, Distereoisomers, Meso structures, Racemic mixture. Resolution of Racemic mixtures. Relative and absolute configuration: D/L and R/S designations. Coverage: 1. Types of Isomers : Comparing Structures 2. Optical Activity 3. Racemic Mixtures : Separation of Racemic Mixtures 4. Enantiomeric Excess and Optical Purity 5. Relative and Absolute Configuration 6. Physical and Chemical Properties of Stereoisomers 2 Stereochemistry Types of Isomers Dr. Rajeev Ranjan 3 Stereochemistry Determining the Relationship Between Two Non-Identical Molecules Dr. Rajeev Ranjan 4 Stereochemistry Comparing Structures: Are the structures connected the same? yes no Are they mirror images? Constitutional Isomers yes no Enantiomers Enantiomers Is there a plane of symmetry? All chiral centers will be opposite between them. yes no Meso Diastereomers superimposable Dr. Rajeev Ranjan 5 Stereochemistry Optical Activity: • The chemical and physical properties of two enantiomers are identical except in their interaction with chiral substances. • The physical property that differs is the behavior when subjected to plane-polarized light ( this physical property is often called an optical property). • Plane-polarized (polarized) light is light that has an electric vector that oscillates in a single plane. -

Effect of the Enantiomeric Ratio of Eutectics on the Results and Products of the Reactions Proceeding with the Participation Of

Perspective Effect of the Enantiomeric Ratio of Eutectics on the Results and Products of the Reactions Proceeding with the Participation of Enantiomers and Enantiomeric Mixtures Emese Pálovics *, Dorottya Fruzsina Bánhegyi and Elemér Fogassy Department of Organic Chemistry and Technology, Budapest University of Technology and Economics, 1521 Budapest, Hungary; [email protected] (D.F.B.); [email protected] (E.F.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +36-1-4632101 Received: 3 August 2020; Accepted: 14 September 2020; Published: 21 September 2020 Abstract: This perspective is focused on the main parameters determining the results of crystallization of enantiomers or enantiomeric mixtures. It was shown that the ratio of supramolecular and helical associations depends on the eutectic composition of the corresponding enantiomeric mixture. The M and P ratios together with the self-disproportionation (SDE) of enantiomers define the reaction of the racemic compound with the resolving agent. Eventually, each chiral molecule reacts with at least two conformers with different degrees of M and P helicity. The combined effect of the configuration, charge distribution, constituent atoms, bonds, flexibility, and asymmetry of the molecules influencing their behavior was also summarized. Keywords: chiral molecules; enantiomeric separation; self-disproportionation of enantiomers; supramolecular associations; helical structure; eutectic composition 1. Introduction The preparation of asymmetric (chiral) compounds (enantiomers) is one of the main goals of research, industry and medicine. The preparation of a given enantiomer is possible in several ways, for example by selective synthesis, which requires the separation of the chiral catalyst or the enantiomers of the racemic compound, and in which case a resolving agent (like a chiral catalyst) may be required. -

Enantioselective Synthesis of the (1S,5R)-Enantiomer of Litseaverticillols a and B

Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem., 70 (10), 2564–2566, 2006 Note Enantioselective Synthesis of the (1S,5R)-Enantiomer of Litseaverticillols A and B y Akira MORITA, Hiromasa KIYOTA, and Shigefumi KUWAHARA Laboratory of Applied Bioorganic Chemistry, Graduate School of Agricultural Science, Tohoku University, Tsutsumidori-Amamiyamachi, Aoba-ku, Sendai 981-8555, Japan Received May 8, 2006; Accepted May 31, 2006; Online Publication, October 7, 2006 [doi:10.1271/bbb.60253] An enantioselective synthesis of the (1S,5R)-enan- which have recently culminated in the first enantiose- tiomer of litseaverticillols A and B was accomplished in lective total synthesis of (1R,5S)-(À)-1 and (1R,5S)-(À)- line with our previously reported synthetic pathway for 2.4) In this note, we describe the synthesis of their their (1R,5S)-enantiomer. The use of ‘‘EtSCeCl2’’ pre- enantiomers directed toward an evaluation of the differ- pared from EtSLi and CeCl3, instead of previously ence in biological activity between the enantiomers of employed EtSLi itself, for the formation of thiol ester litseaverticillols A and B. intermediates prevented any undesirable epimerization Our synthesis of (1S,5R)-1 and (1S,5R)-2 basically occurring in the process. followed our previous synthesis of their corresponding enantiomers, (1R,5S)-1 and (1R,5S)-2, respectively,4) Key words: litseaverticillol; enantioselective synthesis; except that (R)-4-benzyloxazolidin-2-one was employed sesquiterpenoid; anti-HIV as the source of chirality, instead of its (S)-form used in the previous synthesis. Homogeranic -

Lecture 3: Stereochemistry and Drugs Key Objectives: 1

Lecture 3: Stereochemistry and drugs Key objectives: 1. Be able to explain the role of stereochemistry in drug action or metabolism 2. Be able to identify a chiral center (or centers) in a drug 3. Be able to explain the difference between enantiomers and diastereomers Value of chirality and stereochemistry: Chirality as expressed through stereoisomers increases the specificity of molecule recognition and signaling. Like a key in a lock, or a hand in a glove. Some useful definitions: Chirality (and chiral centers): An object (such as a molecule) that is asymmetric and therefore not superimposable on its own image. Chiral centers are the most common features within molecules that give rise to chirality. Stereoisomer: A molecule that possesses at least one chiral center (or center of chirality). Enantiomers: A type of stereoisomer that exists in mirror image forms. See Figure 1. Diastereomers: A type of stereoisomer that possesses more than one chiral center. Stereospecific: A term used to describe a stereochemical property that one isomer possesses but the other does not. For example, the stereospecific metabolism of the S-enantiomer of a compound by an enzyme but the R-enantiomer is not metabolized by that enzyme. Stereoselective: A term used to describe a stereochemical property that is shared by both stereoisomers, but the property is greater in one isomer than the other. For example, the stereoselective binding of the R-enantiomer for a receptor indicates that the S-enantiomer also binds but not as avidly as the R-enantiomer. Enantiomers Figure 1: For enantiomers, many times we use the example of our left and right hands to demonstrate their asymmetry. -

Cross-Linked Protein Crystal Technology in Bioseparation and Biocatalytic Applications

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aaltodoc Helsinki University of Technology, Department of Chemical Technology Technical Biochemistry Report 1/2004 Espoo 2004 TKK-BE-8 CROSS-LINKED PROTEIN CRYSTAL TECHNOLOGY IN BIOSEPARATION AND BIOCATALYTIC APPLICATIONS Antti Vuolanto Dissertation for the degree of Doctor in Science in Technology to be presented with due permission of the Department of Chemical Technology for public examination and debate in Auditorium KE 2 (Komppa Auditorium) at Helsinki University of Technology (Espoo, Finland) on the 20th of August, 2004, at 12 noon. Helsinki University of Technology Department of Chemical Technology Laboratory of Bioprocess Engineering Teknillinen korkeakoulu Kemian osasto Bioprosessitekniikan laboratorio Distribution: Helsinki University of Technology Laboratory of Bioprocess Engineering P.O. Box 6100 FIN-02015 HUT Tel. +358-9-4512541 Fax. +358-9-462373 E-mail: [email protected] ©Antti Vuolanto ISBN 951-22-7176-1 (printed) ISBN 951-22-7177-X (pdf) ISSN 0359-6621 Espoo 2004 Vuolanto, Antti. Cross-linked protein crystal technology in bioseparation and biocatalytic applications. Espoo 2004, Helsinki University of Technology. Abstract Chemical cross-linking of protein crystals form an insoluble and active protein matrix. Cross-linked protein crystals (CLPCs) have many excellent properties including high volumetric activity and stability. In this thesis CLPC technology was studied in bioseparation and biocatalytic applications. A novel immunoaffinity separation material, cross-linked antibody crystals (CLAC), was developed in this thesis for enantiospecific separation of a chiral drug, finrozole. Previously, the preparation of an antibody Fab fragment ENA5His capable of enantiospecific affinity separation of the chiral drug has been described. -

Diastereomers Diastereomers

Diastereomers Diastereomers: Stereoisomers that are not mirror images. enantiomer (R) (S) (S) (R) diastereomers diastereomer diastereomer enantiomer (R) (S) (R) (S) Diastereomers Diastereomers: Stereoisomers that are not mirror images. (R) enantiomer (S) (S) (R) diastereomer To draw the enantiomer of a molecule with chiral centers, invert stereochemistry at all chiral centers. (R) To draw a diastereomer of a molecule (R) with chiral centers, invert stereochemistry at only some chiral centers. Meso Compounds Meso: A molecule that contains chiral centers, but is achiral. 3 Are these molecules chiral? (R) (S) (These are diff eren t f rom th e 3 molecules I just showed; they have 2 -Cl’s, rather than 1 -Cl & 1 -OH. enantiomer (R) (S) (R) (S) These molecules are chiral mirror images of one another. (R,R) and (S,S) are not the same. Meso Compounds Meso: A molecule that contains chiral centers, but is achiral. 3 enantiomer ? (R) (S) (S) (R) no! 3 same molecule! enantiomer (R) (S) (R) (S) Meso Compounds Meso: A molecule that contains chiral centers, but is achiral. 3 enantiomer ? (R) (S) (S) (R) no! 3 same molecule! If a molecule • contains the same number of (R) and (S) stereocenters, and • those stereocenters have identical groups attached, then the molecule is achiral and meso. Meso Compounds Meso: A molecule that contains chiral centers, but is achiral. 3 same molecule (R) (S) (S) (R) 3 meso diastereomers meso diastereomer diastereomer enantiomer (R) (S) (R) (S) chiral chiral Properties of Enantiomers Most physical properties of enantiomers are identical. diethyl-(R,R)-tartrate diethyl-(S,S)-tartrate boiling point 280 °C 280 °C melting point 19 °C 19 °C density 1.204 g/mL 1.204 g/mL refractive index 1.447 1.447 i.e., chirality does not affect most physical properties. -

The Racemate-To-Homochiral Approach to Crystal Engineering Via Chiral Symmetry-Breaking

CrystEngComm The Racemate -to -Homochiral Approach to Crystal Engineering via Chiral Symmetry-Breaking Journal: CrystEngComm Manuscript ID: CE-HIG-02-2015-000402.R1 Article Type: Highlight Date Submitted by the Author: 04-Apr-2015 Complete List of Authors: An, Guanghui; Heilongjiang University, School of Chemistry and Materials Science Yan, Pengfei; Heilongjiang University, School of Chemistry and Materials Science Sun, Jingwen; Heilongjiang University, School of Chemistry and Materials Science Li, Yuxin; School of Chemsitry and Materials Science of Heilongjiang University, Yao, Xu; Heilongjiang University, School of Chemistry and Materials Science Li, Guangming; School of Chemsitry and Materials Science of Heilongjiang University, Page 1 of 12Journal Name CrystEngComm Dynamic Article Links ► Cite this: DOI: 10.1039/c0xx00000x www.rsc.org/xxxxxx ARTICLE TYPE The Racemate-to-Homochiral Approach to Crystal Engineering via Chiral Symmetry-Breaking Guanghui An, a Pengfei Yan, a Jingwen Sun, a Yuxin Li, a Xu Yao, a Guangming Li,* a Received (in XXX, XXX) Xth XXXXXXXXX 20XX, Accepted Xth XXXXXXXXX 20XX 5 DOI: 10.1039/b000000x The racemate-to-homochiral approach is to transform or separate the racemic mixture into homo chiral compounds. This protocol, if without an external chiral source, is categorized into chiral symmetry- breaking. The resolution processes without chiral induction are highly important for the investigation on the origin of homochirality in life, pharmaceutical synthesis, chemical industrial and material science. 10 Besides the study on the models and mechanisms to explain the racemate-to-homochiral approach which may give the probable origin of homochirality in life, the recent developments in this field have been plotted towards the separation of enantiomers for the synthesis of pharmaceuticals, chiral chemicals. -

Enantiomers & Diastereomers

Chapter 5 Stereochemistry Chiral Molecules Ch. 5 - 1 1. Chirality & Stereochemistry An object is achiral (not chiral) if the object and its mirror image are identical Ch. 5 - 2 A chiral object is one that cannot be superposed on its mirror image Ch. 5 - 3 1A. The Biological Significance of Chirality Chiral molecules are molecules that cannot be superimposable with their mirror images O O ● One enantiomer NH causes birth defects, N O the other cures morning sickness O Thalidomide Ch. 5 - 4 HO NH HO OMe Tretoquinol OMe OMe ● One enantiomer is a bronchodilator, the other inhibits platelet aggregation Ch. 5 - 5 66% of all drugs in development are chiral, 51% are being studied as a single enantiomer Of the $475 billion in world-wide sales of formulated pharmaceutical products in 2008, $205 billion was attributable to single enantiomer drugs Ch. 5 - 6 2. Isomerisom: Constitutional Isomers & Stereoisomers 2A. Constitutional Isomers Isomers: different compounds that have the same molecular formula ● Constitutional isomers: isomers that have the same molecular formula but different connectivity – their atoms are connected in a different order Ch. 5 - 7 Examples Molecular Constitutional Formula Isomers C4H10 and Butane 2-Methylpropane Cl Cl C3H7Cl and 1-Chloropropane 2-Chloropropane Ch. 5 - 8 Examples Molecular Constitutional Formula Isomers CH O CH C H O OH and 3 3 2 6 Ethanol Methoxymethane O OCH and 3 C H O OH 4 8 2 O Butanoic acid Methyl propanoate Ch. 5 - 9 2B. Stereoisomers Stereoisomers are NOT constitutional isomers Stereoisomers have their atoms connected in the same sequence but they differ in the arrangement of their atoms in space.