Biggs' Reply in Support of Petition for Special Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

End of Session Report

2014 End of Session Report ARIZONA PEST PROFESSIONALS ORGANIZATION Prepared by: Capitol Consulting, LLC 818 N. 1st Street Phoenix, AZ 85004 www.azcapitolconsulting.com P a g e | 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Dear AZPPO Members: Sine Die! On April 24, 2014, the 51st Arizona Legislature adjourned sine die at 1:46 AM after 101 days in session. By rule a session can last 100 days with provisions in place for extending it. As you recall, those provisions were put to the test last year with the uncomfortably long 151-day session. The 51st Legislature, 2nd Regular Session officially commenced January 13, 2014. A total of 1,205 bills were introduced by the legislature and of those, 276 have been signed by Governor Janice K. Brewer. The session began as usual with the governor announcing policy priorities for the year during the State of the State address. The governor’s priorities were perhaps met with a little more attentiveness from the legislature after a rocky end to the 2013 session. As you may recall part of the Governor’s ambitious 2013 agenda meant crossing political boundaries at the expense of the most conservative within the state’s GOP. In 2013, the governor muscled her way to pass the Medicaid expansion. After weeks of stalled budget negotiations, the Governor called a Special Legislative Session in an effort to bypass House and Senate leadership and call Medicaid to question. The move sparked rumors of a legislative coup and drove a wedge straight through the Republican caucus, dividing the moderate and conservative members. During her final State of the State address in January, Governor Brewer focused on two priorities including a complete overhaul of the state’s defunct child protective services and a proposal to create new incentives for manufactures to set up shop in Arizona. -

Download 2014 Summaries As a High Resolution

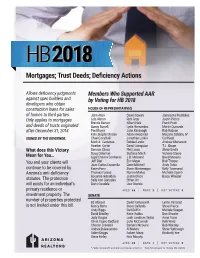

HB2018 Mortgages; Trust Deeds; Deficiency Actions Allows deficiency judgments Members Who Supported AAR against spec builders and by Voting for HB 2018 developers who obtain HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES construction loans for sales of homes to third parties. John Allen David Gowan Jamescita Peshlakai Only applies to mortgages Lela Alston Rick Gray Justin Pierce Brenda Barton Albert Hale Frank Pratt and deeds of trusts originated Sonny Borrelli Lydia Hernandez Martin Quezada after December 31, 2014. Paul Boyer John Kavanagh Bob Robson Kate Brophy McGee Adam Kwasman Macario Saldate, IV SIGNED BY THE GOVERNOR. Chad Campbell Jonathan Larkin Carl Seel Mark A. Cardenas Debbie Lesko Andrew Sherwood Heather Carter David Livingston T.J. Shope What does this Victory Demion Clinco Phil Lovas Steve Smith Doug Coleman Stefanie Mach Victoria Steele Mean for You… Lupe Chavira Contreras J.D. Mesnard David Stevens You and your clients will Jeff Dial Eric Meyer Bob Thorpe Juan Carlos Escamilla Darin Mitchell Andy Tobin continue to be covered by Karen Fann Steve Montenegro Kelly Townsend Arizona’s anti-deficiency Thomas Forese Norma Muñoz Michelle Ugenti Rosanna Gabaldón Justin Olson Bruce Wheeler statutes. The protection Sally Ann Gonzales Ethan Orr will exists for an individual’s Doris Goodale Lisa Otondo primary residence or AYES: 55 | NAYS: 2 | NOT VOTING: 3 investment property. The SENATE number of properties protected Ed Ableser David Farnsworth Lynne Pancrazi is not limited under this bill. Nancy Barto Steve Gallardo Steve Pierce Andy Biggs Gail Griffin Michele Reagan David Bradley Katie Hobbs Don Shooter Judy Burges Leah Landrum Taylor Anna Tovar Olivia Cajero Bedford John McComish Kelli Ward Chester Crandell Barbara McGuire Bob Worsley Andrea Dalessandro Al Melvin Steve Yarbrough Adam Driggs Robert Meza Kimberly Yee Steve Farley Rick Murphy AYES: 29 | NAYS: 1 | NOT VOTING: 0 * Eddie Farnsworth and Warren Petersen voted no – they did not want to change the statute. -

MPHC-Voter-Guide-1.Pdf

CONTENTS VOTING IN THIS ELECTION ................................. 3 LEGISLATIVE DISTRICT 1 ............................... 23 IDENTIFICATION AT THE POLLS ......................... 4 LEGISLATIVE DISTRICT 4 ............................... 25 STATEWIDE RACES ............................................. 5 LEGISLATIVE DISTRICT 12 ............................. 27 GOVERNOR .................................................... 6 LEGISLATIVE DISTRICT 13 ............................. 30 SECRETARY OF STATE ..................................... 7 LEGISLATIVE DISTRICT 15 ............................. 31 ATTORNEY GENERAL ...................................... 7 LEGISLATIVE DISTRICT 16 ............................. 34 SUPERINTENDENT OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION 8 LEGISLATIVE DISTRICT 17 ............................. 36 TREASURER .................................................... 9 LEGISLATIVE DISTRICT 18 ............................. 38 MINE INSPECTOR ......................................... 10 LEGISLATIVE DISTRICT 19 ............................. 40 CORPORATION COMMISSION...................... 11 LEGISLATIVE DISTRICT 20 ............................. 41 FEDERAL RACES ............................................... 13 LEGISLATIVE DISTRICT 21 ............................. 44 U.S. SENATE ................................................. 14 LEGISLATIVE DISTRICT 22 ............................. 46 CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT 1 ....................... 15 LEGISLATIVE DISTRICT 23 ............................. 48 CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT 3 ....................... 16 LEGISLATIVE -

GOLDWATER INSTITUTE What Citizens, Policymakers, and Reporters Should Know

A Reporter’s Guide to the GOLDWATER INSTITUTE What Citizens, Policymakers, and Reporters Should Know Preface Introduction In March 2013, the Center for Media and Democracy and Arizona Working Families jointly released the Reporter’s Guide to the Goldwater Institute, which detailed the institute’s ties to out-of-state corporate interests, huge bonuses awarded to top executives (made possible by taxpayer funds), and murky internal finances. The Blog for Arizona called the report a “must read for anyone who cares about how laws are actually made in Arizona” and the report was subsequently covered in The Arizona Republic, Phoenix New Times, and on KTVK’s evening news program. Conservative economics journalist Jon Talton called on “every Arizonan” to read the “exemplary piece of investigation.” Since the report’s publication, the Goldwater Institute – which shrugged off the report’s findings that it was closely connected to the American Legislative Exchange Council and the Koch brothers as “hardly a surprise” – has continued to work in favor of those interests and against the interests of working Arizonans. The following research updates the original report by cataloging the Goldwater Institute’s most recent efforts to peddle the agenda of ALEC, the Kochs, and corporate interests at the expense of Arizonans. Still Pushing the ALEC Agenda The Reporter’s Guide to the Goldwater Institute and ALEC in Arizona describe how the Goldwater Institute works hand-in-hand with ALEC to push ALEC’s agenda in Arizona. Goldwater, like many ALEC partners, responded indignantly when U.S. Senator Dick Durbin sought information about whether it supports the ALEC/NRA “model legislation” known as “Stand Your Ground” laws, which ALEC has sought to distance itself from in the aftermath of the national outrage over the handling of the George Zimmerman case. -

Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington And

Case 1:15-cv-02038-RC Document 19-1 Filed 07/28/16 Page 1 of 4 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA __________________________________________ ) CITIZENS FOR RESPONSIBILITY AND ) ETHICS IN WASHINGTON, et al., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) Civil Action No. 15-2038 (RC) ) v. ) ) FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION, ) ) Defendant. ) __________________________________________) DECLARATION OF STUART C. MCPHAIL IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT I, STUART C. MCPHAIL, hereby declare under penalty of perjury pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1746 that the following is true and correct: 1. I am an attorney licensed to practice law in the District of Columbia, California, and New York. I am admitted to practice before this Court pro hac vice and my application for admission to the United States District Court for the District of Columbia is currently pending. I am counsel of record for Plaintiffs Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington and Melanie Sloan. I am personally familiar with the facts set forth herein, unless the context indicates otherwise. 2. Attached hereto as Exhibit 1 is a true and correct copy the website titled “Directory of Representatives” published by the United States House of Representatives, as it appeared on the website http://www.house.gov/representatives/ on July 21, 2016. 3. Attached hereto as Exhibit 2 are true and correct copies of the website titled “Political Nonprofits (Dark Money)” published by the Center for Responsive Politics, with either 1 Case 1:15-cv-02038-RC Document 19-1 Filed 07/28/16 Page 2 of 4 the “Cycle to Date” or “Total Cycle” metrics selected, as they appeared on the website http://www.opensecrets.org/outsidespending/nonprof_summ.php?cycle=2016&type=type&range =tot on July 21, 2016. -

2014 Legislative Session Scorecard

2014 LEGISLATIVE SESSION SCORECARD ARIZONA SENATE DISTRICT SENATE MEMBER PARTY SB1062 HB2284 HB2196 1 Steve Pierce R 2 Andrea Dalessandro D 3 Olivia Cajero Bedford D 4 Lynne Pancrazi D 5 Kelli Ward R 6 Chester Crandell R 7 Carlyle Begay D 8 Barbara McGuire D 9 Steve Farley D 10 David Bradley D 11 Al Melvin R 12 Andy Biggs R 13 Don Shooter R 14 Gail Griffin R 15 Nancy Barto R 16 David Farnsworth R 17 Steve Yarbrough R S- 18 John McComish R 19 Anna Tovar D 20 Kimberly Yee R 21 Rick Murphy R 22 Judy Burges R 23 Michele Reagan R 24 Katie Hobbs D 25 Bob Worsley R 26 Ed Ableser D 27 Leah Landrum Taylor D NV 28 Adam Driggs R 29 Steve Gallardo D 30 Robert Meza D Vote Guide: = voted WITH Planned Parenthood = voted AGAINST Planned Parenthood NV = not voting or not present S = Bill Sponsor EXC = Excused 2014 LEGISLATIVE SESSION SCORECARD ARIZONA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES DISTRICT HOUSE MEMBER PARTY SB1062 HB2284 HB2196 1 Karen Fann R 1 Andy Tobin R 2 Rosanna Gabaldon D 2 Demion Clinco D 3 Sally Ann Gonzales D 3 Macario Saldate IV D 4 Juan Carlos Escamilla D 4 Lisa Otondo D 5 Sonny Borrelli R 5 Doris Goodale R 6 Brenda Barton R 6 Bob Thorpe R 7 Jamescita Peshlakai D 7 Albert Hale D 8 Frank Pratt R NV 8 T.J. Shope R 9 Ethan Orr R 9 Victoria Steele D 10 Stefanie Mach D 10 Bruce Wheeler D 11 Adam Kwasman R 11 Steve Smith R 12 Warren Petersen R 12 Eddie Farnsworth R S- 13 Steve Montenegro R 13 Darin Mitchell R 14 David M. -

Arizona Supreme Court Oral Argument Case Summary

ARIZONA SUPREME COURT ORAL ARGUMENT CASE SUMMARY ANDY BIGGS ET AL. v. JANICE K. BREWER ET AL. CV-14-0132-PR PARTIES: Petitioner: Governor Janice K. Brewer and Thomas J. Betlach, Director of the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System Respondents: Andy Biggs, Andy Tobin, Nancy Barto, Judy Burges, Chester Crandell (deceased), Gail Griffin, Al Melvin, Kelli Ward, Steve Yarbrough, Kimberley Yee, John Allen, Brenda Barton, Sonny Borrelli, Paul Boyer, Karen Fann, Eddie Farnsworth, Thomas Forese, David Gowan, Rick Gray, John Kavanagh, Adam Kwasman, Debbie Lesko, David Livingston, Phil Lovas, J.D. Mesnard, Darin Mitchell, Steve Montenegro, Justin Olson, Warren Petersen, Justin Pierce, Carl Seel, Steve Smith, David Stevens, Bob Thorpe, Kelly Townsend, Michelle Ugenti, Jeanette Dubreil, Katie Miller, and Tom Jenney. Amici Curiae in Support of the Petition for Review: (1) Arizona Center for Law in the Public Interest and The William E. Morris Institute for Justice. (2) Fife Symington III, Steve Pierce, Anna Tovar, Leah Landrum Taylor, Bob Worsely, Bob Robson, Heather Carter, Chad Campbell, Lela Alston, Eric Meyer, Kate Brophy McGee, Douglas Coleman, Jeff Dial, Debbie McCune Davis, Ethan Orr, Frank Pratt, T.J. Shope, Victoria Steele, Martin Quezada, Bruce Wheeler, Greater Phoenix Leadership, Southern Arizona Leadership Council, Arizona Chamber of Commerce and Industry, and Greater Phoenix Chamber of Commerce. (3) Arizona Hospital and Healthcare Association, Abrazo Health Care, Banner Health, and Dignity Health Amicus Curiae in Support of the Response to Petition for Review: Pacific Legal Foundation. FACTS: In 1992 Arizona voters approved “Proposition 108,” an initiative measure that added Art. 9, § 22 to the Arizona Constitution. -

IN the SUPREME COURT STATE of ARIZONA ANDY BIGGS; ANDY TOBIN; NANCY Supreme Court BARTO; JUDY BURGES; CHESTER No

IN THE SUPREME COURT STATE OF ARIZONA ANDY BIGGS; ANDY TOBIN; NANCY Supreme Court BARTO; JUDY BURGES; CHESTER No. CRANDELL; GAIL GRIFFIN; AL MELVIN; KELLI WARD; STEVE YARBROUGH; KIMBERLY YEE; JOHN ALLEN; BRENDA BARTON; SONNY BORRELLI; PAUL Court of Appeals BOYER; KAREN FANN; EDDIE Division One FARNSWORTH; THOMAS FORESE; DAVID GOWAN; RICK GRAY; JOHN No. 1 CA-SA 14-0037 KAVANAGH; ADAM KWASMAN; DEBBIE LESKO; DAVID LIVINGSTON; PHIL LOVAS; J.D. MESNARD; DARIN Maricopa County MITCHELL; STEVE MONTENEGRO; JUSTIN OLSON; WARREN PETERSEN; Superior Court JUSTIN PIERCE; CARL SEEL; STEVE No. CV2013-011699 SMITH; DAVID STEVENS; BOB THORPE; KELLY TOWNSEND; MICHELLE UGENTI; JEANETTE DUBREIL; KATIE MILLER; TOM JENNEY, Petitioners, v. THE HONORABLE KATHERINE COOPER, Judge of the SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF ARIZONA, in and for the County of MARICOPA, Respondent Judge, JANICE K. BREWER, in her official capacity as Governor of Arizona; THOMAS J. BETLACH, in his official capacity as Director of the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System, Real Parties in Interest. PETITION FOR REVIEW FENNEMORE CRAIG, P.C. (No. 00022300) Douglas C. Northup (No. 013987) Timothy Berg (No. 004170) Patrick Irvine (No. 006534) Carrie Pixler Ryerson (No. 028072) 2394 East Camelback Road, Suite 600 Phoenix, AZ 85016-3429 Telephone: (602) 916-5000 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Attorneys for Real Parties in Interest Governor Janice K. Brewer and Director Thomas J. Betlach Joseph Sciarrotta, Jr. (No. 017481) Office of Governor Janice K. Brewer 1700 West Washington St., 9th Floor Phoenix, AZ 85007 Telephone: (602) 542-1586 Email: [email protected] Co-Counsel for Real Party in Interest Governor Janice K. -

Dirty Business MOTORSPORTS PARK OPENS AFTER LONG DELAY

www.InMaricopa.com April 2018 GOVERNMENT SENIOR LIVING Difficult year National Parks in school bus retiree finds new inspections use for skills FAMILY Boys vie for Mr. MHS title Dirty Business MOTORSPORTS PARK OPENS AFTER LONG DELAY +Events Calendar State-of-the-Art Facilities GET SPORTS Excellence in Health, Wellness & Education PLUS TODAY! • On-Site Labs • Pediatrics • On-Site Pharmacy • Primary Care • Diabetes Education • Sport Physicals • Integrated • Care Coordination Behavioral Health for 60 On-Site Pharmacists & Doctors Working Together FREEdays! LOS ANGELES Excellence in Health, Wellness & Education ARIZONA • OB/GYN • Postpartum Care • Birth Control • Menopause Delivering at Chandler Regional & • Infertility Evaluations • Incontinence OREGON Banner Casa Grande NATIONAL MOUNTAIN • Prenatal Care • Minimally Invasive Robotic Surgery BAY AREA WASHINGTON PRIMARY CARE & PEDIATRICS CHANDLER MARICOPA (520) 568-2245 (480) 307-9477 (520) 788-6100 44572 W. Bowlin Rd., Maricopa 655 S. Dobson Rd., Ste. 201 44765 W. Hathaway Ave. 520-568-8890 We accept most major insurance, including Medicare & AHCCCS. Uninsured? We can help! Hablamos Español www.orbitelcom.com *Limited time offer for residential customers only. Regular rates apply after promotional period ends. Not valid for services already subscribed to. Additional equipment may be Sun Life is your local non-profit Community Health Center. required. Taxes, franchise fees, installation and other fees not included. Other restrictions may apply. Call office for complete details. www.SunLifeFamilyHealth.org Orbitel_Sports Plus_FREE for 60 days - In Maricopa 8.375x10.875.indd 1 3/6/2018 4:58:45 PM Copple& Copple, p.c. Personal Injury Medical Malpractice Wrongful Death Insurance Bad Faith Empathetic representation with decades BE REAL. -

Alec in Arizona - 2013 Legislative Session

IN ARIZONA The Voice Of Corporate Special Interests In The Halls Of Arizona’s Legislature UPDATED FOR THE FIFTY FIRST LEGISLATURE - April 2013 About this report The lead author on this report was Nick Surgey, Director of Research at the Center for Media and Democracy, with contributions and editing from Lisa Graves, Executive Director at the Center for Media and Democracy. The report also relies upon the work of DBA Press, Progress Now, People For the American Way Foundation, Color of Change, and Common Cause, and upon the hard work and diligent research of many others. For further information on ALEC, and their activities in Arizona and other states, go to www.alecexposed.org 2 Contents KEY FINDINGS .................................................................................................................................................. 4 WHAT IS ALEC? .......................................................................................................................................... 6 ALEC’S CORPORATE “SCHOLARSHIP” FUND IN ARIZONA .................................................. 7 ALEC LEGISLATORS IN ARIZONA...................................................................................................... 11 ALEC MEMBERS IN THE ARIZONA HOUSE............................................................................................................. 11 ALEC MEMBERS IN THE ARIZONA SENATE........................................................................................................... 12 AT HOME IN ARIZONA: ALEC -

Supreme Court of the State of Arizona

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF ARIZONA ANDY BIGGS; ANDY TOBIN; NANCY BARTO; JUDY BURGES; CHESTER CRANDELL; GAIL GRIFFIN; AL MELVIN; KELLI WARD; STEVE YARBROUGH; KIMBERLY YEE; JOHN ALLEN; BRENDA BARTON; SONNY BORRELLI; PAUL BOYER; KAREN FANN; EDDIE FARNSWORTH; THOMAS FORESE; DAVID GOWAN; RICK GRAY; JOHN KAVANAGH; ADAM KWASMAN; DEBBIE LESKO; DAVID LIVINGSTON; PHIL LOVAS; J.D. MESNARD; DARIN MITCHELL; STEVE MONTENEGRO; JUSTIN OLSON; WARREN PETERSEN; JUSTIN PIERCE; CARL SEEL; STEVE SMITH; DAVID STEVENS; BOB THORPE; KELLY TOWNSEND; MICHELLE UGENTI; JEANETTE DUBREIL; KATIE MILLER; TOM JENNEY, Petitioners, v. THE HONORABLE KATHERINE COOPER, JUDGE OF THE SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF ARIZONA, IN AND FOR THE COUNTY OF MARICOPA, Respondent Judge, JANICE K. BREWER, IN HER OFFICIAL CAPACITY AS GOVERNOR OF ARIZONA; THOMAS J. BETLACH, IN HIS OFFICIAL CAPACITY AS DIRECTOR OF THE ARIZONA HEALTH CARE COST CONTAINMENT SYSTEM, Real Parties in Interest. No. CV-14-0132-PR Filed December 31, 2014 Appeal from the Superior Court in Maricopa County The Honorable Katherine M. Cooper, Judge No. CV2013-011699 REVERSED IN PART; REMANDED Opinion of the Court of Appeals, Division One 234 Ariz. 515, 323 P.3d 1166 (2014) AFFIRMED IN PART; VACATED IN PART BIGGS ET AL. v. HON. COOPER ET AL. Opinion of the Court COUNSEL: Clint Bolick, Kurt M. Altman, and Christina Sandefur (argued), Scharf- Norton Center for Constitutional Litigation at the Goldwater Institute, Phoenix, Attorneys for Andy Biggs; Andy Tobin; Nancy Barto; Judy Burges; Chester Crandell; Gail Griffin; Al Melvin; Kelli Ward; Steve Yarbrough; Kimberly Yee; John Allen; Brenda Barton; Sonny Borrelli; Paul Boyer; Karen Fann; Eddie Farnsworth; Thomas Forese; David Gowan; Rick Gray; John Kavanagh; Adam Kwasman; Debbie Lesko; David Livingston; Phil Lovas; J.D. -

Homeowners' Associations Amendments

SB1482 Homeowners’ Associations Amendments; Omnibus Outlines lawful actions Members Who Supported AAR a property management by Voting for SB 1482 company can take on behalf HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of an association (HOA) and establishes rental rights John Allen Doris Goodale Justin Pierce of tenants, unit/property Lela Alston David Gowan Martin Quezada Brenda Barton Rick Gray Bob Robson owners in condominium and Sonny Borrelli John Kavanagh Macario Saldate, IV planned community HOAs. Paul Boyer Jonathan Larkin Carl Seel Kate Brophy McGee Debbie Lesko Andrew Sherwood SIGNED BY THE GOVERNOR. Chad Campbell Stefanie Mach T.J. Shope Mark A. Cardenas J.D. Mesnard Steve Smith Heather Carter Eric Meyer Victoria Steele What does this Victory Demion Clinco Darin Mitchell David Stevens Doug Coleman Steve Montenegro Bob Thorpe Mean for You… Lupe Chavira Contreras Norma Muñoz Andy Tobin Allows a property owner, Jeff Dial Justin Olson Kelly Townsend Karen Fann Ethan Orr Michelle Ugenti through a written designation, Eddie Farnsworth Lisa Otondo Bruce Wheeler to authorize a third party Thomas Forese Jamescita Peshlakai (REALTOR ®/property manager) Rosanna Gabaldón Warren Petersen to act as their agent with AYES: 49 | NAYS: 6 | NOT VOTING: 5 SENATE respect to all HOA matters regarding the rental property. Ed Ableser Steve Farley Rick Murphy Nancy Barto David Farnsworth Lynne Pancrazi Carlyle Begay Steve Gallardo Steve Pierce Andy Biggs Gail Griffin Michele Reagan David Bradley Katie Hobbs Don Shooter Judy Burges Leah Landrum Taylor Anna Tovar Olivia Cajero Bedford John McComish Kelli Ward Chester Crandell Barbara McGuire Bob Worsley Andrea Dalessandro Al Melvin Steve Yarbrough Adam Driggs Robert Meza Kimberly Yee AYES: 30 | NAYS: 0 | NOT VOTING: 0.