Template for HDR Thesis / Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

大洋洲oceania 學校university 迪肯大學deakin University 國家country 澳洲australia 學校簡介introduction As

大洋洲 Oceania 學校 迪肯大學 國家 澳洲 University Deakin University Country Australia As one of Australia's leading tertiary education providers, Deakin offers a personalised experience enhanced by world-class programs and innovative digital engagement. We lead by creating opportunities to live and work in a connected, evolving world. With four outstanding campuses in Melbourne, Geelong and Warrnambool, and a premium online learning platform that exceeds any other in Australia, all 60,000 of our students enjoy unlimited access to world-leading facilities and a friendly, welcoming atmosphere – regardless of whether they're studying on campus or online. We also have 學校簡介 Introduction corporate and learning centres that provide meeting, study and event spaces to both students and the communities we serve. Our passionate academic staff, leadership personnel, administrative staff and researchers make up our rich, vibrant and productive community across four faculties and 14 schools. The University upholds a strong governance system that delivers high standards of decision- making and accountability. This ensures our courses, research and community engagement continues to meet and exceed the highest standards of quality. 秋季 Fall Semester 春季 Spring Semester 學期制度 Academic July to October March - June Calendar Application deadline : Application deadline : 10 April 2022 30 October 2022 交換人數 交換資格 Both undergraduate & 2 FTE Quota Eligibility postgraduate https://policy.deakin.edu.au /document/view- 註冊繳費 Exempted 語言條件 current.php?id=161&_ga=2. Tuition Fee NA for -

Respect. Prevent. Respond. Conference Preventing and Responding to Sexual Harm in the Tertiary Education Sector 5–6 February 2019 | Deakin Downtown

Respect. Prevent. Respond. Conference Preventing and Responding to Sexual Harm in the Tertiary Education Sector 5–6 February 2019 | Deakin Downtown Deakin University CRICOS Provider Code: 00113B deakin.edu.au/RPRconference 1 Deakin’s acknowledgement Deakin acknowledges the Traditional Custodians of our lands and waterways. We pay respects to Elders past, present and emerging. Deakin is committed to valuing, building and sustaining recognition, understanding and positive relationships between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous Australians. 2 Welcome from Deakin University’s Vice-Chancellor Preventing and responding to sexual harassment and sexual assault is a significant issue for our University, our higher education sector and for the wider community. Our campuses are generally safe places. However, we have a addressing the drivers of sexual assault and harassment and responsibility to continue to drive a stronger culture of safety, strengthening a culture of ‘see something say something’, so mutual respect and inclusion. We have a role as employers, that our students and staff will feel comfortable to raise their employees, and as educators of the next generation, to take a concerns and that as institutions, we respond to disclosures in a lead role in ensuring that all who use our grounds and facilities compassionate, empathetic and supportive manner. know that sexual harassment is unacceptable behaviour and The conference program is impressive both in the quality of its sexual assault is criminal behaviour. Both actions have severe speakers and the breadth and depth of the issues it covers. It consequences. We all have a responsibility to lead the way in presents an opportunity to build on our sector’s commitment changing the culture and addressing attitudes and behaviours to fostering an environment where everyone is valued, that are not acceptable in today’s world. -

Supporting Deakin to Become Australia's Most Progressive University

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 DEAKIN COMMERCE ALUMNI SUPPORTING DEAKIN TO BECOME AUSTRALIA’S MOST PROGRESSIVE UNIVERSITY MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE Throughout 2015, the Deakin Commerce Alumni Chapter (‘the Chapter’) continued to build on strong foundations of the founding executive group and the vision of celebrating the achievements of Deakin commerce graduates providing a medium of lifelong communication between Deakin University and its alumni. 2015 has been an exciting year for the On behalf of the Chapter, we extend sincere Chapter. On behalf of the Executive and thanks to all those who committed their Steering Committee, we are pleased to valuable time and resources in support of present to you the 2015 Annual Report. the Chapter’s strategic plan to executing networking events, professional development We hope that you will be inspired by the events and university profile enhancement achievements and continue to be active events. members of the Chapter as we work collaboratively towards helping Deakin We look forward with confidence to the University achieve its mission of becoming Chapter’s future as it continues to add value Australia’s most progressive university. by providing a relevant alumni community to further enhance the careers and personal The Chapter is the largest and most active development of its members. alumni chapter within Deakin University with approximately 15,000 registered members. To date, Chapter members have established a strong presence in commerce nationally and internationally. Deakin graduates today command distinguished positions in the Roger Fredrick public, private and not-for-profit sectors. Deakin Commerce Alumni President 2015 The success of the Chapter is primarily due to the keen participation of the alumni, tireless volunteering efforts of the steering committee members and continued strong support from the Pro Vice Chancellor and staff members from the Faculty of Business and Law and corporate sponsors. -

Higher Education in Regional and Rural Victoria: Distribution, Provision and Access

Melbourne Graduate School of Education HIGHER EDUCATION IN REGIONAL AND RURAL VICTORIA: DISTRIBUTION, PROVISION AND ACCESS Jenny Chesters, Hernan Cuervo and Katherine Romei AUTHORS Dr Jenny Chesters A/ Prof. Hernan Cuervo Ms Katherine Romei The University of Melbourne ISBN: 978 0 7340 5590 3 Date: May 2020 Youth Research Centre Melbourne Graduate School of Education The University of Melbourne, Vic 3010 To cite this report: Chesters, J., Cuervo, H. and Romei, K. 2020 Higher Education in Regional and Rural Victoria: Distribution, Provision and Access. Youth Research Centre, University of Melbourne, Melbourne. All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Youth Research Centre The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Youth Research Centre, the Melbourne Graduate School of Education, or the University of Melbourne. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This report was funded an MSGE 2019 Development Award granted to Dr Jenny Chesters. Photos: Jenny Chesters. 2 Youth Research Centre, Melbourne Graduate School of Education CONTENTS 1. Introduction 4 2. Literature review 6 3. Higher education in the regions 8 4. Availability of courses in regional Victoria 15 5. Conclusion 16 6. References 17 7. Appendices 19 Access to university 3 1. INTRODUCTION Research indicates that students living in regional, rural and Equality of opportunity is dependent upon the availability, remote areas may be disadvantaged on at least two levels: family accessibility and affordability of study options in one’s local socioeconomic status (SES) and geographic location. -

Geelong Waterfront Campus

Accessible parking Bus stop T Accessible toilet Deakin Shuttle Bus Stairs Main entry GEELONG Lift Car park entry Platform lift to level one only WATERFRONT – restricted access by prior Car park arrangement, contact Security CAMPUS Car parking permit Drink station vending machine locations Bicycle rack not to scale CP2 We stern Bea John Hay ch Building (D) Waterfront Kitchen (Level 1) STUDENT Gallery CENTRAL Sally Walker Smythe Building (ad) Street level 2 The Cube T John Hay John Hay Building (D) Courtyard level 3 1 Gheringhap Street Geelong Victoria 3220 et e tr S T m CP3 Gheringhap Street a T h g Jarvis/Brintons n Lt. Smythe Street Lt. Smythe Forecourt Deakin nni Commercial Costa Hall Cu Precinct (C) Building E T CP1 (reserved N parking) Brougham Street Jan 2016 not to scale Geelong Waterfront Campus C = Deakin Commercial Precinct ad = Sally Walker Building D = John Hay Building Student Services Administrative/General Building Level Construction activity Deakin University Student Association STUDENT CENTRAL Accessible shower D1 A number of major developments are under way on campus in 2016. (DUSA) Building D, Level 2 Visit deakin.edu.au/fmsd for more information. ATM D2 Faculty of Business and Law Bike racks (under cover – access via CP1) D1 Parking Faculty of Health Please note that there is no on-campus parking for visitors unless Bookshop (DUSA) D2 School of Nursing and Midwifery special arrangements have been made. Information about car parking Callista Software Services C4 School of Health and Social Development in the surrounding area is available at: Cashier D2 School of Psychology geelongaustralia.com.au/community/parking Chancellery ad 4 School of Architecture and Built Environment Parking availability on campus can be limited, particularly at the Committee for Geelong ad 1 start of Trimester 1. -

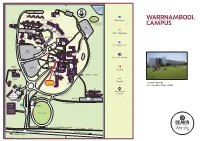

Warrnambool Campus

HOPKINS 5x2hr bays RIVER CP5 CP6 Q Y T 1st tee Student residences golf course Information WARRNAMBOOL Z Golf course patrons parking only X PP CAMPUS CP7 CP4 Public telephones CP12 GingerKitchen W V T H E T N A Accessible toilets L T R A CP2 E V T I C R E B N D A Bus B A L T Accessible parking E R I Stop N T T A T F E O C A D S CP3 N H L 3hr & O O ½hr bays G J CP10 D T G CP1 E2 E Bus stop D E R F I V T E E T SCIENCE LANE I V R Childcare D J N Centre E K E4 T Car park I SECURITY L A Office E5 S CP9 E V T I U R D N Parking permit K S O Warehousing Tennis, Netball, H N vending machine J O Distribution Basketball courts Centre 4x2hr bays Princes Highway a r k CP8 o p i n g Warrnambool Victoria 3280 CP11 N L O D G E South D R I V E I Pavilion West Drink Station Institute locations of TAFE Sports Oval IVE R Dry weather car park around oval AITKEN D Sherwood Park Railway Station RAILWAY LINE PRINCES HIGHWAY To Warrnambool To Melbo urne Jan 2016 Warrnambool Campus South West Institute of TAFE First turn left just inside the Campus entrance Academic/Research Building Level Administrative/General Building Construction activity Aquaculture Research Facility Q ATM H A number of major developments are under way on campus in 2016. -

Deakin University 2020 International Students Undergraduate Course Guide

Study area International students | 2020 Undergraduate Course Guide Melbourne | Geelong | Warrnambool | Cloud Campus (online) deakin.edu.au/international 1 Study area Welcome Deakin University, Australia, provides a world-class education Welcome to Deakin – recognised around the globe. We offer you the chance to gain the your study destination knowledge, skills and experience to make an impact. Let us help you achieve your career goals. G’day and welcome! Campus locations Australia is one of the world’s most popular international study Deakin has four modern campuses in three unique locations. destinations, with thousands of students arriving every year. Like You will discover some of Australia’s most popular destinations, Australia, Deakin University is a welcoming community, and we incredible wildlife, and engaging and friendly culture when support our international students to ensure they have a safe and you study here. The University also offers courses through its enjoyable study experience. innovative online Cloud Campus. World-class degrees Scholarships Deakin offers a wide range of study areas and we can help you Deakin offers many different scholarships to assist choose the right degree to pursue your dream career. Be ready high-achieving international students throughout their studies. to take your next step with confidence and gain the experience To check if you are eligible for a Deakin scholarship, visit you need to succeed. Deakin is highly ranked in many study areas, deakin.edu.au/scholarships. which you can learn more about in this guide. Trimester system Career focus Deakin runs on a Trimester system whereby our courses start in Deakin applies a practical focus across all its programs. -

A Guide for Parents and Families Deakin University Located in Australia: Melbourne | Geelong | Warrnambool | Cloud (Online)

A guide for parents and families Deakin University Located in Australia: Melbourne | Geelong | Warrnambool | Cloud (online) deakin.edu.au/int-parents 1 Welcome to Deakin I am delighted to introduce you and your family to Deakin University – a leading Australian university with a strong international reputation in education and research. Deakin offers an exceptional study experience, degrees that prepare our students for the jobs of the future, and a safe and welcoming environment. The parents and families of our international students play such an important role in supporting and guiding their child in their choice of university, and making sure their transition into higher education is an enjoyable one. I want to assure you that Deakin University is here to do the same, to nurture your child to be the best they can be, and to ensure they enjoy every step along the way. As one of Australia’s largest universities, Deakin has extensive global networks, world-class research and, most importantly, an educational portfolio that combines the best of campus and digital delivery into a highly supportive and personalised study experience. We will continue to be innovative and ambitious by exploring new approaches in teaching and learning. Deakin is a leader in the use of digital platforms and resources, and we are always expanding our community and industry connections, in Australia and abroad, to ensure our university offers students a globally recognised and respected qualification. We look forward to providing you with more information about Deakin University and how we can help your child succeed. I look forward to welcoming them to Deakin one day soon. -

Issue 6 2019 Deakin Alumni Magazine Celebrating 40 Years of Alumni

DEAKIN ALUMNI MAGAZINE ISSUE 6 2019 CELEBRATING 40 YEARS OF ALUMNI 02 DKIN CELEBRATING 40 YEARS OF ALUMNI IMPACT 1978 04 Message from 08 Christopher Kelly 24 Pasan Muthumala our President and Alumnus Class of 1969 Alumnus Class of Vice-Chancellor 2005 and 2007 Professor 10 Wayne Eason Jane den Hollander AO Alumnus Class of 1978 26 Jyoti Shekar Alumna Class of 2008 06 Stay 12 Tony Arnel Connected Alumnus Class of 1979 28 Lauren Hewitt Alumna Class of 2010 14 John Stanhope AM Alumnus Class of 1982 30 Naqib Azha 16 Sharn Bedi Alumnus Class of 2013 Alumna Class of 1995 32 Bennett Merriman 18 Renuke Coswatte Alumnus Class of 2009 Alumnus Class of 2003 + 20 Sadie-Jane Nunis Shannan Gove Alumna Class of 2003 Alumnus Class of 2014 22 Lawrence Lau 34 Melanie Orvis Alumnus Class of 2004 Alumna Class of 2016 Deakin University Information in this publication CRICOS Provider Code: 00113B was correct at time of printing. DKIN 03 AND RESEARCH THAT WILL CHANGE OUR 2018 FUTURE 36 Prison 60 Robots to 78 Giving break the rescue to Deakin Professor Joe Graffam Doctor Mick Fielding 42 Saving the 66 Sensing 79 Deakin Baw Baw frog motion Advancement Professor Don Driscoll and Associate Professor PhD student Thomas Burns Pubudu Pathirana 48 The magic 72 The dark of realism side of emoji Associate Professor Doctor Elizabeth Kirley Maria Takolander and Associate Professor Marilyn McMahon 54 Recalibrating multiculturalism Professor Fethi Mansouri Creative direction and design: Writing: Photography: Studio Binocular Betty Vassiliadis Craig Newell unless otherwise credited 04 DKIN Welcome to dKin 2018. -

Warrnambool Campus Identification Parking Wellbeing Office Central Campus Map Centre

ID Building Accessible Health and Security Carpark Student Warrnambool Campus Identification parking Wellbeing Office Central Campus Map Centre Major Water Recreational Pathway Road Flexicar Construction Area Zone Deakin is commited to ensuring the health and safety of our students, staff and University community. Find out more at deakin.edu.au/covidsafe A B C D E F G Hopkins River 1 CP 5 CP 6 Q Y 5x2hr bays Student Residences Z N P 2 CP 7 CP 4 Brother W Fox V H 3 ART LANE TO HYCEL CP 2 C 4 B A CAFETERIA LANE D G LODGE DRIVE CP 1 E CP 10 5 F T SCIENCE LANE J E3 AITKEN DRIVE E4 L E5 S 6 E IV DR K CP 9 SON Tennis, Netball, JOHN Basketball courts = 7 LODGE DRIVE CP 11 South I West Institute of TAFE Sports Oval 8 AITKEN DRIVE Sherwood Park Railway Station 9 PRINCES HIGHWAY To Warrnambool To Melbourne Princes Highway, Warrnambool, Victoria Trimester 2, 2021 Current as at 15 June 2021 ID Building Accessible Health and Security Carpark Student Warrnambool Campus Identification parking Wellbeing Office Central Mobility Map Centre Major Water Recreational Pathway Road Flexicar Construction Area Sealed path Unsealed path Zone Flat or near flat Flat or near flat Deakin is commited to ensuring the health and safety of our students, staff Gradient 1:20 Gradient 1:20 and University community. Find out more at deakin.edu.au/covidsafe Gradient 1:14 Gradient 1:14 A B C D E F G Hopkins CP 5 River 1 CP 6 Q Y 5x2hr bays Student Residences Z N P 2 CP 7 CP 4 Brother Fox V W H 3 ART LANE TO HYCEL CP 2 C 4 B A CAFETERIA LANE D LODGE DRIVE G CP 1 E 5 CP 10 F -

Warrnambool Campus

HOPKINS 5x2hr bays RIVER CP5 CP6 Q Y T 1st tee Student residences golf course Information WARRNAMBOOL Z Golf course patrons parking only X PP CAMPUS CP7 CP4 Public telephones CP12 GingerKitchen W V H E T T N A Accessible toilets L T R A CP2 E V T I C R E B N D L A B A T Accessible parking I N T E R A F E T T O C A D S CP3 N H L 3hr & O O ½hr bays G J CP10 D T G CP1 E2 E Bus stop D E R F I V T E E T SCIENCE LANE I V R E3 Childcare D J N Centre E K E4 T Car park I SECURITY Princes Highway L A Oce E5 S CP9 Warrnambool Victoria 3280 E I V U T R D Drink Station N K S O locations Tennis, Netball, H N Warehousing J O Distribution Basketball courts Centre 4x2hr bays a r k CP8 o p i n g CP11 N L O D G E D R I V E South I Pavilion West Institute of TAFE Sports Oval E IV R D Dry weather car park around oval A I T K E N Sherwood Park Railway Station R A I L W A Y L I N E PRINCES HIGHW AY To Warrnambool To Melb ourne JNovember 2016 Warrnambool Campus South West Institute of TAFE First turn left just inside the Campus entrance Academic/Research Building Level Administrative/General Building Construction activity Aquaculture Research Facility Q ATM H A number of major developments are under way on campus in 2016. -

Thursday 27Th

Thursday 27th May Opening ceremony (Live session plenary 10:00am AEST) New York London Hong Kong Melbourne 26 May 20:00 27 May 1:00 27 May 8:00 27 May 10:00 Acknowledgement of Country Welcome to APBEN 2021 A/Prof Dominique Martin, Deakin University, Australia Welcome to Deakin University Prof Gary Rogers, Deakin University, Australia Building bioethics education in the Asia Pacific – why we must work together Prof HK Ng, Chinese University of Hong Kong, China Values and inclusivity in ethics education (Session on demand) Title Speaker Bioethics curriculum, what is the difference means between Eastern Prof Yali Cong, Peking University, and Western perspectives? China Personal encounters and placement experiences: do they influence Prof Stephen Tobin, Western Sydney student values in meaningful ways? University, Australia Empowering Resettled Refugee Populations Through Inclusive Tanner McGuire, Northeast Ohio Bioethics Education Medical University* What’s the issue? Redesigning an ethics seminar to foster an inclusive Dr Cynthia Forlini and Dr Jacqueline and relational learning environment for medical students Savardi, Deakin University, Australia* Raising awareness of values and ethics in radiography education, a John McInerney, Monash University, small scale qualitative study Australia* Humanization of medical education in the Republic of Belarus Dr Hanna Klimovich, Belarusian State Medical University, Belarus* Thinking about what matters in health ethics education (Live session plenary – 13:00pm AEST) New York London Hong Kong Melbourne