Listening to Voices – Perspectives from the Tatmadaw's Rank and File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karen-Burmese Refugees

Karen-Burmese Refugees An orientation for health workers and volunteers Developed by Christine Dziedzic, Student Project Officer Community Nutrition Unit, Annerley Road Community Health Background Information • The Karen-Burmese live in mountainous jungle regions of Myanmar (southern and eastern), and Thailand • Myanmar is located in South- East Asia – Formally known as Burma – Developing and largely rural – Bordered by China, Tibet, Laos, Thailand, Bangladesh and India Source: cyberschoolbus.un.org Community Nutrition Unit, Annerley Road Community Health P: (07) 3010 3550 Myanmar - Background InformationWorld Health Organisation (2006) • Population: 50 519 000 • Life expectancy at birth: – 61 years • Infant mortality rate – Per 1000 live births: 106 – 4.7 / 1000 in Australia (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2006) • Language: Burmese – Indigenous peoples have their own languages Flag of Myanmar – Over 126 dialects Source: cyberschoolbus.un.org Community Nutrition Unit, Annerley Road Community Health P: (07) 3010 3550 History of Myanmar • 1886: Became a province of British India • 1948: Gained independence • 1962: Military dictatorship took power – Large outflow of refugees • 1988: Martial law declared – Increased refugee numbers • State of civil war for much of the past 50 years Community Nutrition Unit, Annerley Road Community Health P: (07) 3010 3550 Ethnic Groups • Major ethnic group: Burmese • Largest indigenous population: Karen • Other indigenous races include: – Shans – Chins – Mon – Rakhine – Katchin • Ethnic tension -

1 Myanmar Update

Myanmar Update – 15 February 2021 Summary • The Myanmar coup will likely lead to escalating civil resistance and a consequent heavy- handed military response. • The military will continue to expand control over the internet – leading to frequent “blackouts” • Monitoring the human rights situation as well as providing aid and development support will become increasingly difficult in the months ahead. Background to the November 2020 Elections Myanmar experienced five years of relative political stability after the Tatmadaw (Myanmar Armed Forces) handed power to State Counsellor (a position roughly analogous to Prime Minister) Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) following the November 2015 elections – which ended almost 50 years of military rule. Even then, however, the Tatmadaw retained substantial power, including the right to appoint a quarter of parliamentarians and control of key ministries. Elections to both Myanmar’s upper house - Amyotha Hluttaw - and lower house - Pyithu Hluttaw – took place on 8 November 2020. Suu Kyi’s NLD won a popular landslide, taking 161 (of the 224) seats in the Amyotha Hluttaw and 315 (of the 440) in the Pyithu Hluttaw, an even larger margin than in 2015. This equated to 83% of the available seats, while the Tatmadaw’s proxy, the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), won a total of just 33 seats. The USDP immediately began making accusations of fraud after the vote although the Union Election Commission said there was no proof to support these claims and there has been little or no independent evidence either. The Tatmadaw also disputed the results, claiming that the vote was fraudulent, perhaps fearing that the NLD, with its majority, would amend the constitution to reduce the Tatmadaw’s political influence – a longstanding NLD campaign pledge. -

Myanmar Buddhism of the Pagan Period

MYANMAR BUDDHISM OF THE PAGAN PERIOD (AD 1000-1300) BY WIN THAN TUN (MA, Mandalay University) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2002 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the people who have contributed to the successful completion of this thesis. First of all, I wish to express my gratitude to the National University of Singapore which offered me a 3-year scholarship for this study. I wish to express my indebtedness to Professor Than Tun. Although I have never been his student, I was taught with his book on Old Myanmar (Khet-hoà: Mranmâ Râjawaà), and I learnt a lot from my discussions with him; and, therefore, I regard him as one of my teachers. I am also greatly indebted to my Sayas Dr. Myo Myint and Professor Han Tint, and friends U Ni Tut, U Yaw Han Tun and U Soe Kyaw Thu of Mandalay University for helping me with the sources I needed. I also owe my gratitude to U Win Maung (Tampavatî) (who let me use his collection of photos and negatives), U Zin Moe (who assisted me in making a raw map of Pagan), Bob Hudson (who provided me with some unpublished data on the monuments of Pagan), and David Kyle Latinis for his kind suggestions on writing my early chapters. I’m greatly indebted to Cho Cho (Centre for Advanced Studies in Architecture, NUS) for providing me with some of the drawings: figures 2, 22, 25, 26 and 38. -

Buddhism in Myanmar a Short History by Roger Bischoff © 1996 Contents Preface 1

Buddhism in Myanmar A Short History by Roger Bischoff © 1996 Contents Preface 1. Earliest Contacts with Buddhism 2. Buddhism in the Mon and Pyu Kingdoms 3. Theravada Buddhism Comes to Pagan 4. Pagan: Flowering and Decline 5. Shan Rule 6. The Myanmar Build an Empire 7. The Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries Notes Bibliography Preface Myanmar, or Burma as the nation has been known throughout history, is one of the major countries following Theravada Buddhism. In recent years Myanmar has attained special eminence as the host for the Sixth Buddhist Council, held in Yangon (Rangoon) between 1954 and 1956, and as the source from which two of the major systems of Vipassana meditation have emanated out into the greater world: the tradition springing from the Venerable Mahasi Sayadaw of Thathana Yeiktha and that springing from Sayagyi U Ba Khin of the International Meditation Centre. This booklet is intended to offer a short history of Buddhism in Myanmar from its origins through the country's loss of independence to Great Britain in the late nineteenth century. I have not dealt with more recent history as this has already been well documented. To write an account of the development of a religion in any country is a delicate and demanding undertaking and one will never be quite satisfied with the result. This booklet does not pretend to be an academic work shedding new light on the subject. It is designed, rather, to provide the interested non-academic reader with a brief overview of the subject. The booklet has been written for the Buddhist Publication Society to complete its series of Wheel titles on the history of the Sasana in the main Theravada Buddhist countries. -

Anti-Rohingya Laws Timeline

Materials ANTI-ROHINGYA LAWS TIMELINE A police checkpoint with closed-off Rohingya area, Rakhine State, 2014. (WikiCommons/Adam) 1942 1948 1962 1978 1982 1988 1992 - 1997 2012 1942 January 4, 1948 March 2, 1962 1978 October 15 August 8 Attempts by Burmese and June 2-14 and October Bangladesh governments British Burma is occupied Burma’s Independence from Myanmar becomes a “Operation Dragon King”: Citizenship Law: the “8888 Uprising”: failed Rakhine State Riots: a series to repatriate Rohingya from by the Imperial Japanese Great Britain. dictatorship ruled by the Tatmadaw launches a Rohingya are no longer pro-democracy protests of riots in the state of Rakhine Bangladesh refugee camps Army. Muslim Rohingya in the military (Tatmadaw). “clearance operation” against recognised as one of the bring Aung San Suu Kyi, after a local ethnic Rakhine to Myanmar. More Rohingya Rakhine (formerly Arakan) the Rohingya causing 135 “national races” and daughter of Burmese woman was allegedly raped and flee Myanmar at the same time State are armed in support more than 200,000 to flee become stateless. independence leader murdered by three Rohingya and as conditions there have not of the British, while the Myanmar and go to refugee Aung San and leader a Rakhine mob murdered ten improved. Buddhists of Rakhine support camps in Bangladesh. of the newly formed Muslims in response. the Japanese. National League for Democracy, into the public spotlight. 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2013 2014 May 23 October 9 August 25 March 2018 A law prohibiting inter- Census: A nationwide Population Control Healthcare Law: women 2016 “Clearance Operation”: Villages are burnt: Human Rights Watch Satellite imageries ethnicity and inter-faith census is held for the in some regions are subjected to three- Tatmadaw launches a “clearance “Clearance Operation”: after confirm the Burmese government is bulldozing the burned marriages is passed. -

What About the Rohingya?

UPPSALA UNIVERSITY Department of Theology Master Programme in Religion in Peace and Conflict Master thesis, 30 credits Spring, 2019 Supervisor: Håkan Bengtsson What about the Rohingya? A study searching for power relations in different levels of society Ewa Einarsson Abstract This study aims to search for patterns that demonstrate power relations. It specifically seeks to identify patterns in the power relations in the Rohingya conflict and understand the established power relations at different levels in society, which could provide a picture of the social world within the context of historical, ethnic, cultural, religious and political circumstances. Moreover, this study illustrates the Rohingya population’s experience with relations of power. The ongoing conflict in Myanmar, which is based on religion, ethnicity and politics, is seemingly without any solution. Myanmar is depicted as a country that has lost both hope and legitimacy for the political system and has reduced chances to establish a society in which all the minorities are included across the spheres of society. Finding a bright future for the Rohingya population might be difficult; nevertheless, this study seeks to enhance the understanding of the ongoing conflict and the underlying power relations. 2 Table of Contents A study searching for power relations in different levels of society ................................................................. 1 ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... -

New Crisis Brewing in Burma's Rakhine State?

CRS INSIGHT New Crisis Brewing in Burma's Rakhine State? February 15, 2019 (IN11046) | Related Author Michael F. Martin | Michael F. Martin, Specialist in Asian Affairs ([email protected], 7-2199) Approximately 250 Chin and Rakhine refugees entered into Bangladesh's Bandarban district in the first week of February, trying to escape the fighting between Burma's military, or Tatmadaw, and one of Burma's newest ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), the Arakan Army (AA). Bangladesh's Foreign Minister Abdul Momen summoned Burma's ambassador Lwin Oo to protest the arrival of the Rakhine refugees and the military clampdown in Rakhine State. Bangladesh has reportedly closed its border to Rakhine State. U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Myanmar Yanghee Lee released a press statement on January 18, 2019, indicating that heavy fighting between the AA and the Tatmadaw had displaced at least 5,000 people. She also called on the Rakhine State government to reinstate the access for international humanitarian organizations. The Conflict Between the Arakan Army and the Tatmadaw The AA was formed in Kachin State in 2009, with the support of the Kachin Independence Army (KIA). In 2015, the AA moved some of its soldiers from Kachin State to southwestern Chin State, and began attacking Tatmadaw security bases in Chin State and northern Rakhine State (see Figure 1). In late 2017, the AA shifted more of its operations into northeastern Rakhine State. According to some estimates, the AA has approximately 3,000 soldiers based in Chin and Rakhine States. Figure 1. Reported Clashes between Arakan Army and Tatmadaw Source: CRS, utilizing data provided by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED). -

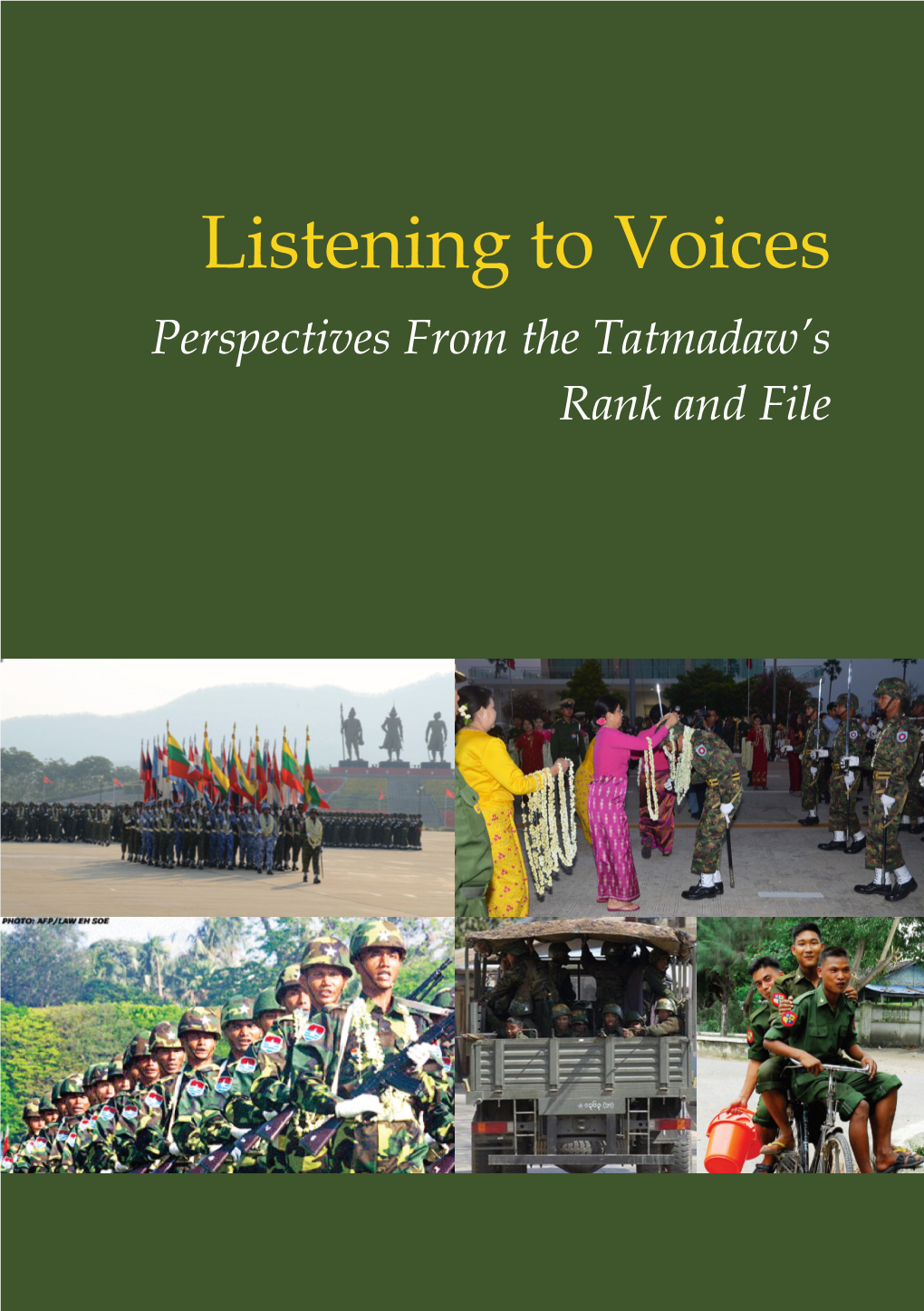

Listening to Voices Perspectives from the Tatmadaw’S Rank and File

Listening to Voices Perspectives From the Tatmadaw’s Rank and File Listening to Voices – Perspectives From the Tatmadaw’s Rank and File 1 Methodology and training: Soth Plai Ngarm Project coordinaton and writng: Amie Kirkham Writng and editng support: Raymond Hyma, Amelia Breeze, Sarah Clarke Layout by: Boonruang Song-ngam Published by: The Centre for Peace and Confict Studies (CPCS), 2015 Funding Support: The Royal Norwegian Embassy, Myanmar, Dan Church Aid ISBN: 9 789996 381768 2 Contents Acknowledgements .............................................................. 4 Preface ................................................................................. 5 A Brief History of the Tatmadaw ........................................... 9 Implementaton and Method ............................................. 14 Findings in Brief .................................................................. 20 Expanding Main Themes .................................................... 23 Peace and the peace process .............................................. 23 Development needs included in negotatons .................... 32 Life in the rank and fle ........................................................ 34 The future: challenges and needs ....................................... 36 Overcoming Prejudice – insights from the listeners ............. 40 Conclusions and Opportunites ........................................... 43 Bibliography ....................................................................... 45 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The young men and -

Burma Road to Poverty: a Socio-Political Analysis

THE BURMA ROAD TO POVERTY: A SOCIO-POLITICAL ANALYSIS' MYA MAUNG The recent political upheavals and emergence of what I term the "killing field" in the Socialist Republic of Burma under the military dictatorship of Ne Win and his successors received feverish international attention for the brief period of July through September 1988. Most accounts of these events tended to be journalistic and failed to explain their fundamental roots. This article analyzes and explains these phenomena in terms of two basic perspec- tives: a historical analysis of how the states of political and economic devel- opment are closely interrelated, and a socio-political analysis of the impact of the Burmese Way to Socialism 2, adopted and enforced by the military regime, on the structure and functions of Burmese society. Two main hypotheses of this study are: (1) a simple transfer of ownership of resources from the private to the public sector in the name of equity and justice for all by the military autarchy does not and cannot create efficiency or elevate technology to achieve the utopian dream of economic autarky and (2) the Burmese Way to Socialism, as a policy of social change, has not produced significant and fundamental changes in the social structure, culture, and personality of traditional Burmese society to bring about modernization. In fact, the first hypothesis can be confirmed in light of the vicious circle of direct controls-evasions-controls whereby military mismanagement transformed Burma from "the Rice Bowl of Asia," into the present "Rice Hole of Asia." 3 The second hypothesis is more complex and difficult to verify, yet enough evidence suggests that the tradi- tional authoritarian personalities of the military elite and their actions have reinforced traditional barriers to economic growth. -

The Rohingyas of Rakhine State: Social Evolution and History in the Light of Ethnic Nationalism

RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF ORIENTAL STUDIES Eurasian Center for Big History & System Forecasting SOCIAL EVOLUTION Studies in the Evolution & HISTORY of Human Societies Volume 19, Number 2 / September 2020 DOI: 10.30884/seh/2020.02.00 Contents Articles: Policarp Hortolà From Thermodynamics to Biology: A Critical Approach to ‘Intelligent Design’ Hypothesis .............................................................. 3 Leonid Grinin and Anton Grinin Social Evolution as an Integral Part of Universal Evolution ............. 20 Daniel Barreiros and Daniel Ribera Vainfas Cognition, Human Evolution and the Possibilities for an Ethics of Warfare and Peace ........................................................................... 47 Yelena N. Yemelyanova The Nature and Origins of War: The Social Democratic Concept ...... 68 Sylwester Wróbel, Mateusz Wajzer, and Monika Cukier-Syguła Some Remarks on the Genetic Explanations of Political Participation .......................................................................................... 98 Sarwar J. Minar and Abdul Halim The Rohingyas of Rakhine State: Social Evolution and History in the Light of Ethnic Nationalism .......................................................... 115 Uwe Christian Plachetka Vavilov Centers or Vavilov Cultures? Evidence for the Law of Homologous Series in World System Evolution ............................... 145 Reviews and Notes: Henri J. M. Claessen Ancient Ghana Reconsidered .............................................................. 184 Congratulations -

"Jesus Is Not a Foreign God":Christian Music-Making in Burma/ Myanmar

University of Dayton eCommons Music Faculty Publications Department of Music 2021 "Jesus Is Not a Foreign God":Christian Music-Making in Burma/ Myanmar Heather MacLachlan University of Dayton, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/mus_fac_pub Part of the Music Commons eCommons Citation MacLachlan, Heather, ""Jesus Is Not a Foreign God":Christian Music-Making in Burma/Myanmar" (2021). Music Faculty Publications. 23. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/mus_fac_pub/23 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Music at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ‘Jesus Is Not A Foreign God’: Baptist Music Making in Burma/Myanmar Christians in the Southeast Asian country of Burma, also known as Myanmar, make up approximately five percent of the national population. The Christian community of Burma includes both Catholics and Protestants, and the Protestants are divided into many denominations. Baptist Christians are predominant among this group, and they provided most of the ethnographic information upon which this article is based. In the article I argue that twenty-first century Baptists in Burma fulfill both aspects of a “twofold legacy” bequeathed to them by Adoniram Judson, the first Baptist missionary to Burma, and that their fulfillment of this legacy is manifest in their musical practices. I further argue that it has been, and continues to be, to Burmese Baptists’ advantage to emphasize both aspects of this religious legacy, because at various times both aspects have highlighted their affiliation with more powerful groups inside Burma. -

Burma Coup Watch

This publication is produced in cooperation with Burma Human Rights Network (BHRN), Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK (BROUK), the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), Progressive Voice (PV), US Campaign for Burma (USCB), and Women Peace Network (WPN). BN 2021/2031: 1 Mar 2021 BURMA COUP WATCH: URGENT ACTION REQUIRED TO PREVENT DESTABILIZING VIOLENCE A month after its 1 February 2021 coup, the military junta’s escalation of disproportionate violence and terror tactics, backed by deployment of notorious military units to repress peaceful demonstrations, underlines the urgent need for substantive international action to prevent massive, destabilizing violence. The junta’s refusal to receive UN diplomatic and CONTENTS human rights missions indicates a refusal to consider a peaceful resolution to the crisis and 2 Movement calls for action confrontation sparked by the coup. 2 Coup timeline 3 Illegal even under the 2008 In order to avert worse violence and create the Constitution space for dialogue and negotiations, the 4 Information warfare movement in Burma and their allies urge that: 5 Min Aung Hlaing’s promises o International Financial Institutions (IFIs) 6 Nationwide opposition immediately freeze existing loans, recall prior 6 CDM loans and reassess the post-coup situation; 7 CRPH o Foreign states and bodies enact targeted 7 Junta’s violent crackdown sanctions on the military (Tatmadaw), 8 Brutal LIDs deployed Tatmadaw-affiliated companies and partners, 9 Ongoing armed conflict including a global arms embargo; and 10 New laws, amendments threaten human rights o The UN Security Council immediately send a 11 International condemnation delegation to prevent further violence and 12 Economy destabilized ensure the situation is peacefully resolved.