THE ANNALS of IOWA 73 (Winter 2014)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civil War Collection Crab Orchard, Kentucky Give Them All My Kind Oct 17Th 1862 and Warm Regards

Norwegian-American Historical Association Vol 142 Summer 2011 From the NAHA Offi ce to Association Members I T I A Sneak Peak at Norwegian- Elias Molee, a unique character in American Studies, Volume 36 the annals of Norwegian-American Civil War Letter 2 history, who would have preferred to Translated e Norwegian-American Historical be remembered here as elias molee Association is pleased to return to for reasons Professor Slind explains. The NAHA Civil War 4 publication after a hiatus to reorder Slind is Professor of History at Luther Collection the finances and governance of the College in Decorah, Iowa. Emeritus organization. It is a particular pleasure Professor of History Gary D. Olson New Acquisitions 6 this fall to present the thirty-sixth of Augustana College in Sioux Falls, volume in a series that began in 1926 South Dakota, has contributed an ably From the Front Desk 8 with what was then called Studies drawn demographic profile of the and Records. Through the years the Norwegian-American community in NAHA-Norge Seminar 9 format and content have changed Sioux Falls based on census data. His somewhat, but most volumes of the method and findings will help link Hired for Battle 11 series—now known as Norwegian- Norwegian-American research to a American Studies—have presented a growing body of research in American Odd Lovoll Honor 12 miscellany, including both essays and and transatlantic history. Carol presentations of primary sources. Colburn and Laurann Gilbertson, of Vesterheim Museum in Decorah, The present volume continues in that Iowa, turn our attention to the work tradition. -

Civil War Letters of Colonel Hans Christian Heg: a Norwegian Regiment in the American Civil War Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2015 2015 9780873519557 Theodore C

Civil War Letters of Colonel Hans Christian Heg: A Norwegian Regiment in the American Civil War Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2015 2015 9780873519557 Theodore C. Blegen The book is a primarily a collection of letters written by the soldiers to their loved ones back home in Wisconsin. Their outlook on life could be summed up using common "Scandi- hoovian" saying of 'It Could Be Worse." Table of Contents. Letters from Colonel Heg and Others. Andersonville and Other Southern Prisons. An address by Ole Steensland. The Battle of Murfreesboro or Stone's River by Waldemar Ager. The Battle of Chattanooga by Waldemar Ager. Machine generated contents note: The Norwegian Regiment in the American Civil War -- by Waldemar Ager 3 -- Observations from the Civil War -- by Ben (Bersven) Nelson 11 -- The Norwegian Regiment at Chickamauga -- by Waldemar Ager 54 -- Letters Written at the Front 63 -- From Morten J. Nordre’s Diary 136 The Civil War Letters Of Colonel Hans Christian Heg: A Norwegian Regiment I Brand New. S$ 27.05. Customs services and international tracking provided. Buy It Now. +S$ 47.75 shipping estimate. from United States. TSZpYAonso3rZY21Ced. Michigan in the Civil War 13th Colonel's Private Letters Buell Stevenson 1862. S$ 20.79. Customs services and international tracking provided. Buy It Now. +S$ 52.84 shipping estimate. from United States. 3 watchers. The Civil War Letters Of Colonel Hans Christian Heg gives an overview of his life's history followed by numerous personal letters relating to his days and demise during the Civil War period of American history. For those looking for the shared feelings of a man in war and his personal every-day communications, this is the book for you. -

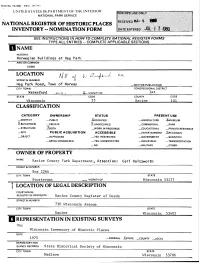

Nomination Form I Name Location

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS __________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ I NAME HISTORIC Norwegian Buildings at Heg Park_____________________________ AND/OR COMMON same LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Heg Park Road, Town of Norway _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY TOWN . CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Water-ford /t^c c , JL_ VICINITY OF 1st STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Wisconsin 55 Racine 101 CLASSIFICATION OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —PUBLIC —XOCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE J^MUSEUM —PRIVATE ^.UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK STRUCTURE —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT ^RELIGIOUS OBJECT _IN PROCESS _YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER. OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Racine County Park Department, Attention: Carl Holtzworth STREET & NUMBER Box 226A CITY, TOWN STATE Sturtevant VICINITY OF Wisconsin 53177 ! LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Racine County Register of Deeds STREET & NUMBER 730 Wisconsin Avenue CITY. TOWN STATE Racine Wisconsin 53402 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TJTLE Wisconsin Inventory of Historic Places DATE 1975 —FEDERAL JLSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS State Historical Society of Wisconsin CITY. TOWN STATE Madison Wisconsin 53706 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED _UNALTERED —ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS JkLTERED ?_MOVED r>ATF 1928, 1933 _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Both historic buildings in the Heg Memorial Park have been moved from their original locations to the present site. Each building has been restored to accurately reflect the environment of the early years of Norwegian settlement. -

University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding o f the dissertation. -

Newsletter February 2021

SolskinnSolskinn NyhetsbrevNyhetsbrev February 2021 Newsletter from Solskinn Lodge 6-150 Happy Ord fra Presidenten Valentines Day The New President Alle Hjerters Dag Social and installation of lodge officers on ZOOM Greetings Solskinn Lodge Members. Hmmm it seems like I have been here before. For our new members I was lodge president a number of years ago. I do work fulltime at Eisenhower Health, treating pts every day. I am also the District Six President of Sons of Norway, with responsibilities for over 5,000 members in California, Nevada, Arizona, Utah, New Mexico and Colorado. I like to read and participate in the Solskinn Book Group. I am excited for the return of our craft group now on ZOOM. I hope you all can participate in one of these activities. As you can see from my photos I got my COVID-19 vaccination. I have gotten both of my vaccinations and have my vaccination card. I now see a light at the end of the tunnel and hope that we will be able to actually meet again and share conversation and food. I hope to see you all on ZOOM until the time we can meet in person, whether it is for our social, the book group or craft group. It is nice to stay connected to each other. It helps us all through these difficult times. Invite a friend or neighbor to join us. Just send them the link and they are welcome to visit with us. I am honored and look forward to serving as your lodge president. Fraternally Luella In this issue Page 1 Ord fra Presidenten Present on ZOOM Social on ZOOM Installation of officers Row 1: Page 2 Fjord Horse (Fjording) -

The Battle of Stones River 2020-2021 Speaker Schedule

General Orders No. 1-21 January 7, 2021 Christopher L. Kolakowski January 2020 The Battle of Stones River IN THIS ISSUE Your country owes you an immense debt. God grant that you may quadruple the MCWRT News …………………….…………..… page 2 obligation. From the Archives …………..…..……………..page 3 Salmon P. Chase to Rosecrans after Stones River Area Events ……………………………………….. page 3 From the Field ……………….…..….….... pages 4-5 According to The American Battlefield Trust, the casualty percentage at Round Table Speakers 2020-2021 …….. page 6 the Battle of Stones River was second only to the Battle of Gettysburg in 2020-2021 Board of Directors ……..……. page 6 all of the major engagements of the Civil War. Throughout five days of Meeting Reservation Form …………….…. page 6 battle, the most intense being December 31 and January 2, the National Between the Covers..………….……….. pages 7-8 Park Service claims that nearly 24,000 men on both sides became Wanderings ……………………………………… pages 9 casualties out of 81,000 engaged – a 29% casualty rate. Gettysburg had a Through the Looking Glass ….…..…. page 10-11 casualty rate of 31%. Chickamauga, Shiloh, and Antietam had casualty In Memoriam …………………………………… page 11 rates of 29%, 26%, and 18%, respectively. The staggering losses at Stones Items of Note ……………………………... page 12-13 River compelled both armies to spend months trying to regain their Quartermaster’s Regalia ………..………… page 14 strength and come to terms with the causes of the winter bloodshed. On January 1, 1862, Braxton Bragg did not renew the Confederate attack January Meeting at a Glance at Stones River which allowed Rosecrans to strengthen his position and The Wisconsin Club receive reinforcements. -

Freeing the Slaves: an Examination of Emancipation Military Policy

FREEING THE SLAVES: AN EXAMINATION OF EMANCIPATION MILITARY POLICY AND THE ATTITUDES OF UNION OFFICERS IN THE WESTERN THEATER DURING THE CIVIL WAR by KRISTOPHER ALLEN TETERS GEORGE C. RABLE, COMMITTEE CHAIR LAWRENCE F. KOHL KARI FREDERICKSON ANDREW HUEBNER MARK GRIMSLEY A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2012 Copyright Kristopher Allen Teters 2012 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the policies and attitudes of Union officers towards emancipation in the western theater during the Civil War. It looks at how both high-ranking and junior Federal officers carried out emancipation policy in the field and how this policy evolved over time. Alongside army policy this study discusses how western officers viewed emancipation, black troops, and race in general. It ultimately determines how much officers’ attitudes towards these issues changed as a result of the war. From the beginning of the war to the middle of 1862, Union armies in the West pursued a very inconsistent emancipation policy. When Congress passed the Second Confiscation Act in July 1862, army policy became much more consistent and emancipationist. Officers began to take in significant numbers of slaves and employ them in the army. After President Abraham Lincoln issued the final Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863, the army increased its liberation efforts and this continued until the war’s end. In fact, the army became the key instrument by which emancipation was implemented in the field. But always guiding these emancipation policies were military priorities. -

The Hardship of Civil War Soldiering on Danish Immigrant Families

The Bridge Volume 37 Number 1 Article 6 2014 "I long to hear from you": The Hardship of Civil War Soldiering on Danish Immigrant Families Anders Bo Rasmussen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/thebridge Part of the European History Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, and the Regional Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Rasmussen, Anders Bo (2014) ""I long to hear from you": The Hardship of Civil War Soldiering on Danish Immigrant Families," The Bridge: Vol. 37 : No. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/thebridge/vol37/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Bridge by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. "I long to hear from you": The Hardship of Civil War Soldiering on Danish Immigrant Families by Anders Bo Rasmussen [Al number of Danish men( ... ) participated in the bloody Civil War in this country from 1861 to 1865 ( ... )future historical inquiry into this area will have ample occasion to go back to the right sources and will undoubtedly procure a considerable material about those of our countrymen who fought the long and stubborn fight( .. ) [It] will be of great interest to our people's history in America! --P.S. Vig Danske i Amerika, 1907.1 In 1917 the Danish American minister and immigrant historian Peter S0rensen Vig published Danske i krig i og for Amerika (Danes Fighting in and for America). Vig had taken it upon himself to take a deeper look into the Danish Civil War experience, at a time when Norwegian American immigrants had already published several books about their war service. -

“They Were Among Our Finest”

(Periodicals postage paid in Seattle, WA) TIME DATED MATERIAL — DO NOT DELAY This week on Norway.com This week in the paper Building the tallest Ski jumper Midsummer bonfire Dette er den riktige, den kraftige sommer. Tom Hilde sets a in Ålesund Den slipper regn når det trengs, men den world record har forkjærlighet for solskinn. in mini ski Read more at blog.norway.com - Nils Kjær Read more on page 5 Norwegian American Weekly Vol. 121, No. 26 July 2, 2010 7301 Fifth Avenue NE Suite A, Seattle, WA 98115 • Tel (800) 305-0217 • www.norway.com $1.50 per copy Online News Dateline Oslo “They were among our finest” Oslo aims to be electric car capital of the world Four Norwegian City officials in Oslo seem intent soldiers killed on making the Norwegian capital the world’s electric car capital as June 27 by well. It now can boast the highest roadside bomb in number of recharging stations per capita in the world, and is the home Faryab province of some major el-car producers. Last week the city formally opened in northern a large new recharging station, free of charge for el-car owners, right Afghanistan near the popular inner harbour and adjacent to the waterfront Aker CO M PILED BY DRE W GARDNER Brygge complex. The station also Norwegian American Weekly offers free parking for el-cars, for up to 16 hours. It costs NOK 48 The Norwegian Ministry of (USD 7.75) per hour to park on the street just next to the el-car lot and Defense reports that on Sunday af- even more in a nearby garage. -

In This Issue: Online Catalog Goes Live! Battle of Kringen - 400 Years Later! Visit to Norway with Monroe by C

VOLUME 36 | NUMBER 2 | WINTER 2012 In this issue: Online Catalog Goes Live! Battle of Kringen - 400 Years Later! Visit to Norway with Monroe By C. Marvin Lang Miller Sunday, August 26, 2012, was bright and sunny along ploys. Rather than use the well trod paths, Klungnes the northern stretches of the River Lågen in central took them through swamps, up heavily wooded sloops, Olive Nordby Woodblock Print Norway. Church bells peeled from the ancient church and even over mountainous terrain. Of course, his Card of Sell, several kilometers north of the City of Otta tactics were “delaying” - allowing the signal fires to be Norse Valley Lodge Work Day located deep within the Gudbrandsdal. A four day set and the “budstikke” passed the word – “Enemy in festival was being concluded with an ecumenical service, County send out message.” Civil War Website Update bringing together for worship Norwegians, Scots, and Summer Classes Americans. Such was not the case 400 years ago! The night of August 25th was spent in the shadow On that date (a Sunday by the Gregorian Calendar, of the stavkirke, Nord Sel – known as the church Svein Ludvigsen Visit a Wednesday by the Julian Calendar), a group of of Kristen Lavransdatter in Sigrid Undset’s famous Recent Acquisitions Norwegian farmers trilogy. A large – men, women, and farm is across the Norwegian Visitors perhaps children road from the – ambushed and church, known Destination Stoughton Weekend annihilated an as Romundgård, Publications of Note invading troop neighbor to of Scottish Jorundgård, mercenaries. That Kristen’s home. It event has become was at Romund- known as the gård that the Scots Family History Battle of Kringen spent their last and the victory has evening. -

May 13, 2021 Kevin Hampton General Orders No

May 13, 2021 Kevin Hampton General Orders No. 5-21 May 2021 Our Adopted Country is in Danger IN THIS ISSUE The Service of Hans Heg and the Scandinavians MCWRT News …………………….…………..… page 2 of the 15th Wisconsin Infantry From the Archives …………..…..……………..page 3 Area Events ……………………………………….. page 3 The 15th Wisconsin Volunteer Regiment was From the Field ……………….…..….….... pages 4-5 originally formed by Col. Hans Heg at Camp Between the Covers ……………………..… page 6-7 Randall, near Madison, Wisconsin. The majority Round Table Speakers 2019-2020……… page 8 of its members were Norwegian immigrants 2019-2020 Board of Directors ……..……. page 8 with the rest being mainly Swedish and Danish Meeting Reservation Form …………….…. page 8 immigrants. Organized in Madison, the regiment Boston Corbett Story ..………..……….. page 9-10 mustered into federal service January 31, 1862. Westerners by Lance Herdegen ………. page 11 The motto of the regiment became: For God Through the Looking Glass …….…... page 12-13 and Our Country. The regiment mustered out of Quartermaster’s Regalia ………..………… page 14 service by company between December 1, 1864, and February 13, 1865. May Meeting at a Glance Hans Christian Heg was heavily involved in the recruitment of the 15th The Wisconsin Club Wisconsin and wrote an appeal that appeared in the Wisconsin 900 W. Wisconsin Avenue Norwegian language newspaper. [Jackets required for the dining room.] Scandinavians! Let us understand the situation, our duty and our responsibility. Shall 6:15 p.m. - Registration/Social Hour 6:45 p.m. - Dinner the future ask, where were the Scandinavians when the Fatherland was saved? [$30 by reservation, please] In October 1862, Heg led his regiment into their first big battle at Perryville. -

Hans Heg Statue

Who was Hans Heg, whose statue was torn down in Madison? Here's why the Civil War hero was memorialized. Teryl Franklin | Wisconsin State Journal 20 hrs ago The statue of Col. Hans Christian Heg, torn down by protesters at the state Capitol on June 23, honored a Norwegian immigrant from Wisconsin who died fighting for the Union Army in the Civil War. “The State has sent no braver soldier, and no truer patriot to aid in this mighty struggle for national unity, than Hans Christian Heg,” the State Journal wrote Sept. 29, 1863, reporting word of his death. “The valorous blood of the old Vikings ran in his veins, united with the gentler virtues of a Christian and a gentlemen.” Heg was mortally wounded in the bloody Battle of Chickamauga on Sept. 19 of that year and died the next day. The highest-ranked Wisconsin officer killed in combat during the Civil War, Heg commanded a regiment largely composed of other Scandinavian immigrants. He was 33 years old. Heg settled in the Racine area with his parents in 1840 and lived in Wisconsin for all but one year, when he mined for Gold in the West before moving home to take over his family's farm. In 1859, he was elected to the statewide office of prison commander, "earning a reputation as a pragmatic reformer," according to the state Historical Society. Heg found an outlet for his anti-slavery views when he was tapped to lead his Union brigade. The monument to Heg was unveiled on Capitol Square in October 1926 before a crowd of about 2,000 people.