Block Ciphers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard

Lecture 3: Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard Lecture Notes on “Computer and Network Security” by Avi Kak ([email protected]) January 26, 2021 3:43pm ©2021 Avinash Kak, Purdue University Goals: To introduce the notion of a block cipher in the modern context. To talk about the infeasibility of ideal block ciphers To introduce the notion of the Feistel Cipher Structure To go over DES, the Data Encryption Standard To illustrate important DES steps with Python and Perl code CONTENTS Section Title Page 3.1 Ideal Block Cipher 3 3.1.1 Size of the Encryption Key for the Ideal Block Cipher 6 3.2 The Feistel Structure for Block Ciphers 7 3.2.1 Mathematical Description of Each Round in the 10 Feistel Structure 3.2.2 Decryption in Ciphers Based on the Feistel Structure 12 3.3 DES: The Data Encryption Standard 16 3.3.1 One Round of Processing in DES 18 3.3.2 The S-Box for the Substitution Step in Each Round 22 3.3.3 The Substitution Tables 26 3.3.4 The P-Box Permutation in the Feistel Function 33 3.3.5 The DES Key Schedule: Generating the Round Keys 35 3.3.6 Initial Permutation of the Encryption Key 38 3.3.7 Contraction-Permutation that Generates the 48-Bit 42 Round Key from the 56-Bit Key 3.4 What Makes DES a Strong Cipher (to the 46 Extent It is a Strong Cipher) 3.5 Homework Problems 48 2 Computer and Network Security by Avi Kak Lecture 3 Back to TOC 3.1 IDEAL BLOCK CIPHER In a modern block cipher (but still using a classical encryption method), we replace a block of N bits from the plaintext with a block of N bits from the ciphertext. -

Related-Key Cryptanalysis of 3-WAY, Biham-DES,CAST, DES-X, Newdes, RC2, and TEA

Related-Key Cryptanalysis of 3-WAY, Biham-DES,CAST, DES-X, NewDES, RC2, and TEA John Kelsey Bruce Schneier David Wagner Counterpane Systems U.C. Berkeley kelsey,schneier @counterpane.com [email protected] f g Abstract. We present new related-key attacks on the block ciphers 3- WAY, Biham-DES, CAST, DES-X, NewDES, RC2, and TEA. Differen- tial related-key attacks allow both keys and plaintexts to be chosen with specific differences [KSW96]. Our attacks build on the original work, showing how to adapt the general attack to deal with the difficulties of the individual algorithms. We also give specific design principles to protect against these attacks. 1 Introduction Related-key cryptanalysis assumes that the attacker learns the encryption of certain plaintexts not only under the original (unknown) key K, but also under some derived keys K0 = f(K). In a chosen-related-key attack, the attacker specifies how the key is to be changed; known-related-key attacks are those where the key difference is known, but cannot be chosen by the attacker. We emphasize that the attacker knows or chooses the relationship between keys, not the actual key values. These techniques have been developed in [Knu93b, Bih94, KSW96]. Related-key cryptanalysis is a practical attack on key-exchange protocols that do not guarantee key-integrity|an attacker may be able to flip bits in the key without knowing the key|and key-update protocols that update keys using a known function: e.g., K, K + 1, K + 2, etc. Related-key attacks were also used against rotor machines: operators sometimes set rotors incorrectly. -

KLEIN: a New Family of Lightweight Block Ciphers

KLEIN: A New Family of Lightweight Block Ciphers Zheng Gong1, Svetla Nikova1;2 and Yee Wei Law3 1Faculty of EWI, University of Twente, The Netherlands fz.gong, [email protected] 2 Dept. ESAT/SCD-COSIC, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium 3 Department of EEE, The University of Melbourne, Australia [email protected] Abstract Resource-efficient cryptographic primitives become fundamental for realizing both security and efficiency in embedded systems like RFID tags and sensor nodes. Among those primitives, lightweight block cipher plays a major role as a building block for security protocols. In this paper, we describe a new family of lightweight block ciphers named KLEIN, which is designed for resource-constrained devices such as wireless sensors and RFID tags. Compared to the related proposals, KLEIN has ad- vantage in the software performance on legacy sensor platforms, while its hardware implementation can be compact as well. Key words. Block cipher, Wireless sensor network, Low-resource implementation. 1 Introduction With the development of wireless communication and embedded systems, we become increasingly de- pendent on the so called pervasive computing; examples are smart cards, RFID tags, and sensor nodes that are used for public transport, pay TV systems, smart electricity meters, anti-counterfeiting, etc. Among those applications, wireless sensor networks (WSNs) have attracted more and more attention since their promising applications, such as environment monitoring, military scouting and healthcare. On resource-limited devices the choice of security algorithms should be very careful by consideration of the implementation costs. Symmetric-key algorithms, especially block ciphers, still play an important role for the security of the embedded systems. -

Chapter 3 – Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard

Symmetric Cryptography Chapter 6 Block vs Stream Ciphers • Block ciphers process messages into blocks, each of which is then en/decrypted – Like a substitution on very big characters • 64-bits or more • Stream ciphers process messages a bit or byte at a time when en/decrypting – Many current ciphers are block ciphers • Better analyzed. • Broader range of applications. Block vs Stream Ciphers Block Cipher Principles • Block ciphers look like an extremely large substitution • Would need table of 264 entries for a 64-bit block • Arbitrary reversible substitution cipher for a large block size is not practical – 64-bit general substitution block cipher, key size 264! • Most symmetric block ciphers are based on a Feistel Cipher Structure • Needed since must be able to decrypt ciphertext to recover messages efficiently Ideal Block Cipher Substitution-Permutation Ciphers • in 1949 Shannon introduced idea of substitution- permutation (S-P) networks – modern substitution-transposition product cipher • These form the basis of modern block ciphers • S-P networks are based on the two primitive cryptographic operations we have seen before: – substitution (S-box) – permutation (P-box) (transposition) • Provide confusion and diffusion of message Diffusion and Confusion • Introduced by Claude Shannon to thwart cryptanalysis based on statistical analysis – Assume the attacker has some knowledge of the statistical characteristics of the plaintext • Cipher needs to completely obscure statistical properties of original message • A one-time pad does this Diffusion -

A Block Cipher Algorithm to Enhance the Avalanche Effect Using Dynamic Key- Dependent S-Box and Genetic Operations 1Balajee Maram and 2J.M

International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics Volume 119 No. 10 2018, 399-418 ISSN: 1311-8080 (printed version); ISSN: 1314-3395 (on-line version) url: http://www.ijpam.eu Special Issue ijpam.eu A Block Cipher Algorithm to Enhance the Avalanche Effect Using Dynamic Key- Dependent S-Box and Genetic Operations 1Balajee Maram and 2J.M. Gnanasekar 1Department of CSE, GMRIT, Rajam, India. Research and Development Centre, Bharathiar University, Coimbatore. [email protected] 2Department of Computer Science & Engineering, Sri Venkateswara College of Engineering, Sriperumbudur Tamil Nadu. [email protected] Abstract In digital data security, an encryption technique plays a vital role to convert digital data into intelligible form. In this paper, a light-weight S- box is generated that depends on Pseudo-Random-Number-Generators. According to shared-secret-key, all the Pseudo-Random-Numbers are scrambled and input to the S-box. The complexity of S-box generation is very simple. Here the plain-text is encrypted using Genetic Operations and S-box which is generated based on shared-secret-key. The proposed algorithm is experimentally investigates the complexity, quality and performance using the S-box parameters which includes Hamming Distance, Balanced Output and the characteristic of cryptography is Avalanche Effect. Finally the comparison results motivates that the dynamic key-dependent S-box has good quality and performance than existing algorithms. 399 International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics Special Issue Index Terms:S-BOX, data security, random number, cryptography, genetic operations. 400 International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics Special Issue 1. Introduction In public network, several types of attacks1 can be avoided by applying Data Encryption/Decryption2. -

A Tutorial on the Implementation of Block Ciphers: Software and Hardware Applications

A Tutorial on the Implementation of Block Ciphers: Software and Hardware Applications Howard M. Heys Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John's, Canada email: [email protected] Dec. 10, 2020 2 Abstract In this article, we discuss basic strategies that can be used to implement block ciphers in both software and hardware environments. As models for discussion, we use substitution- permutation networks which form the basis for many practical block cipher structures. For software implementation, we discuss approaches such as table lookups and bit-slicing, while for hardware implementation, we examine a broad range of architectures from high speed structures like pipelining, to compact structures based on serialization. To illustrate different implementation concepts, we present example data associated with specific methods and discuss sample designs that can be employed to realize different implementation strategies. We expect that the article will be of particular interest to researchers, scientists, and engineers that are new to the field of cryptographic implementation. 3 4 Terminology and Notation Abbreviation Definition SPN substitution-permutation network IoT Internet of Things AES Advanced Encryption Standard ECB electronic codebook mode CBC cipher block chaining mode CTR counter mode CMOS complementary metal-oxide semiconductor ASIC application-specific integrated circuit FPGA field-programmable gate array Table 1: Abbreviations Used in Article 5 6 Variable Definition B plaintext/ciphertext block size (also, size of cipher state) κ number -

Construction of Stream Ciphers from Block Ciphers and Their Security

Sridevi, International Journal of Computer Science and Mobile Computing, Vol.3 Issue.9, September- 2014, pg. 703-714 Available Online at www.ijcsmc.com International Journal of Computer Science and Mobile Computing A Monthly Journal of Computer Science and Information Technology ISSN 2320–088X IJCSMC, Vol. 3, Issue. 9, September 2014, pg.703 – 714 RESEARCH ARTICLE Construction of Stream Ciphers from Block Ciphers and their Security Sridevi, Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science, Karnatak University, Dharwad Abstract: With well-established encryption algorithms like DES or AES at hand, one could have the impression that most of the work for building a cryptosystem -for example a suite of algorithms for the transmission of encrypted data over the internet - is already done. But the task of a cipher is very specific: to encrypt or decrypt a data block of a specified length. Given an plaintext of arbitrary length, the most simple approach would be to break it down to blocks of the desired length and to use padding for the final block. Each block is encrypted separately with the same key, which results in identical ciphertext blocks for identical plaintext blocks. This is known as Electronic Code Book (ECB) mode of operation, and is not recommended in many situations because it does not hide data patterns well. Furthermore, ciphertext blocks are independent from each other, allowing an attacker to substitute, delete or replay blocks unnoticed. The feedback modes in fact turn the block cipher into a stream cipher by using the algorithm as a keystream generator. Since every mode may yield different usage and security properties, it is necessary to analyse them in detail. -

Optimization of Core Components of Block Ciphers Baptiste Lambin

Optimization of core components of block ciphers Baptiste Lambin To cite this version: Baptiste Lambin. Optimization of core components of block ciphers. Cryptography and Security [cs.CR]. Université Rennes 1, 2019. English. NNT : 2019REN1S036. tel-02380098 HAL Id: tel-02380098 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02380098 Submitted on 26 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THÈSE DE DOCTORAT DE L’UNIVERSITE DE RENNES 1 COMUE UNIVERSITE BRETAGNE LOIRE Ecole Doctorale N°601 Mathématique et Sciences et Technologies de l’Information et de la Communication Spécialité : Informatique Par Baptiste LAMBIN Optimization of Core Components of Block Ciphers Thèse présentée et soutenue à RENNES, le 22/10/2019 Unité de recherche : IRISA Rapporteurs avant soutenance : Marine Minier, Professeur, LORIA, Université de Lorraine Jacques Patarin, Professeur, PRiSM, Université de Versailles Composition du jury : Examinateurs : Marine Minier, Professeur, LORIA, Université de Lorraine Jacques Patarin, Professeur, PRiSM, Université de Versailles Jean-Louis Lanet, INRIA Rennes Virginie Lallemand, Chargée de Recherche, LORIA, CNRS Jérémy Jean, ANSSI Dir. de thèse : Pierre-Alain Fouque, IRISA, Université de Rennes 1 Co-dir. de thèse : Patrick Derbez, IRISA, Université de Rennes 1 Remerciements Je tiens à remercier en premier lieu mes directeurs de thèse, Pierre-Alain et Patrick. -

Chapter 2 the Data Encryption Standard (DES)

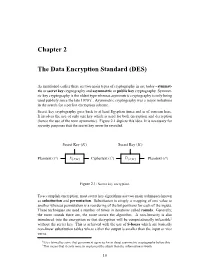

Chapter 2 The Data Encryption Standard (DES) As mentioned earlier there are two main types of cryptography in use today - symmet- ric or secret key cryptography and asymmetric or public key cryptography. Symmet- ric key cryptography is the oldest type whereas asymmetric cryptography is only being used publicly since the late 1970’s1. Asymmetric cryptography was a major milestone in the search for a perfect encryption scheme. Secret key cryptography goes back to at least Egyptian times and is of concern here. It involves the use of only one key which is used for both encryption and decryption (hence the use of the term symmetric). Figure 2.1 depicts this idea. It is necessary for security purposes that the secret key never be revealed. Secret Key (K) Secret Key (K) ? ? - - - - Plaintext (P ) E{P,K} Ciphertext (C) D{C,K} Plaintext (P ) Figure 2.1: Secret key encryption. To accomplish encryption, most secret key algorithms use two main techniques known as substitution and permutation. Substitution is simply a mapping of one value to another whereas permutation is a reordering of the bit positions for each of the inputs. These techniques are used a number of times in iterations called rounds. Generally, the more rounds there are, the more secure the algorithm. A non-linearity is also introduced into the encryption so that decryption will be computationally infeasible2 without the secret key. This is achieved with the use of S-boxes which are basically non-linear substitution tables where either the output is smaller than the input or vice versa. 1It is claimed by some that government agencies knew about asymmetric cryptography before this. -

Chapter 2 Block Ciphers

Chapter 2 Block Ciphers Block ciphers are the central tool in the design of protocols for shared-key cryp- tography. They are the main available “technology” we have at our disposal. This chapter will take a look at these objects and describe the state of the art in their construction. It is important to stress that block ciphers are just tools—raw ingredients for cooking up something more useful. Block ciphers don’t, by themselves, do something that an end-user would care about. As with any powerful tool, one has to learn to use this one. Even a wonderful block cipher won’t give you security if you use don’t use it right. But used well, these are powerful tools indeed. Accordingly, an important theme in several upcoming chapters will be on how to use block ciphers well. We won’t be emphasizing how to design or analyze block ciphers, as this remains very much an art. The main purpose of this chapter is just to get you acquainted with what typical block ciphers look like. We’ll look at two examples, DES and AES. DES is the “old standby.” It is currently (year 2001) the most widely-used block cipher in existence, and it is of sufficient historical significance that every trained cryptographer needs to have seen its description. AES is a modern block cipher, and it is expected to supplant DES in the years to come. 2.1 What is a block cipher? A block cipher is a function E: {0, 1}k ×{0, 1}n →{0, 1}n that takes two inputs, a k- bit key K and an n-bit “plaintext” M, to return an n-bit “ciphertext” C = E(K, M). -

Recommendation for Block Cipher Modes of Operation Methods

NIST Special Publication 800-38A Recommendation for Block 2001 Edition Cipher Modes of Operation Methods and Techniques Morris Dworkin C O M P U T E R S E C U R I T Y ii C O M P U T E R S E C U R I T Y Computer Security Division Information Technology Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899-8930 December 2001 U.S. Department of Commerce Donald L. Evans, Secretary Technology Administration Phillip J. Bond, Under Secretary of Commerce for Technology National Institute of Standards and Technology Arden L. Bement, Jr., Director iii Reports on Information Security Technology The Information Technology Laboratory (ITL) at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) promotes the U.S. economy and public welfare by providing technical leadership for the Nation’s measurement and standards infrastructure. ITL develops tests, test methods, reference data, proof of concept implementations, and technical analyses to advance the development and productive use of information technology. ITL’s responsibilities include the development of technical, physical, administrative, and management standards and guidelines for the cost-effective security and privacy of sensitive unclassified information in Federal computer systems. This Special Publication 800-series reports on ITL’s research, guidance, and outreach efforts in computer security, and its collaborative activities with industry, government, and academic organizations. Certain commercial entities, equipment, or materials may be identified in this document in order to describe an experimental procedure or concept adequately. Such identification is not intended to imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, nor is it intended to imply that the entities, materials, or equipment are necessarily the best available for the purpose. -

Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

Optimizations in Algebraic and Differential Cryptanalysis Theodosis Mourouzis Department of Computer Science University College London A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2015 Title of the Thesis: Optimizations in Algebraic and Differential Cryptanalysis Ph.D. student: Theodosis Mourouzis Department of Computer Science University College London Address: Gower Street, London, WC1E 6BT E-mail: [email protected] Supervisors: Nicolas T. Courtois Department of Computer Science University College London Address: Gower Street, London, WC1E 6BT E-mail: [email protected] Committee Members: 1. Reviewer 1: Professor Kenny Paterson 2. Reviewer 2: Dr Christophe Petit Day of the Defense: Signature from head of PhD committee: ii Declaration I herewith declare that I have produced this paper without the prohibited assistance of third parties and without making use of aids other than those specified; notions taken over directly or indirectly from other sources have been identified as such. This paper has not previously been presented in identical or similar form to any other English or foreign examination board. The following thesis work was written by Theodosis Mourouzis under the supervision of Dr Nicolas T. Courtois at University College London. Signature from the author: Abstract In this thesis, we study how to enhance current cryptanalytic techniques, especially in Differential Cryptanalysis (DC) and to some degree in Al- gebraic Cryptanalysis (AC), by considering and solving some underlying optimization problems based on the general structure of the algorithm. In the first part, we study techniques for optimizing arbitrary algebraic computations in the general non-commutative setting with respect to sev- eral metrics [42, 44].