University Microfilms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Men, Women, and Property in Trollope's Novels Janette Rutterford

Accounting Historians Journal Volume 33 Article 9 Issue 2 December 2006 2006 Frank must marry money: Men, women, and property in Trollope's novels Janette Rutterford Josephine Maltby Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_journal Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation Rutterford, Janette and Maltby, Josephine (2006) "Frank must marry money: Men, women, and property in Trollope's novels," Accounting Historians Journal: Vol. 33 : Iss. 2 , Article 9. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_journal/vol33/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Archival Digital Accounting Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Accounting Historians Journal by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rutterford and Maltby: Frank must marry money: Men, women, and property in Trollope's novels Accounting Historians Journal Vol. 33, No. 2 December 2006 pp. 169-199 Janette Rutterford OPEN UNIVERSITY INTERFACES and Josephine Maltby UNIVERSITY OF YORK FRANK MUST MARRY MONEY: MEN, WOMEN, AND PROPERTY IN TROLLOPE’S NOVELS Abstract: There is a continuing debate about the extent to which women in the 19th century were involved in economic life. The paper uses a reading of a number of novels by the English author Anthony Trollope to explore the impact of primogeniture, entail, and the mar- riage settlement on the relationship between men and women and the extent to which women were involved in the ownership, transmission, and management of property in England in the mid-19th century. INTRODUCTION A recent Accounting Historians Journal article by Kirkham and Loft [2001] highlighted the relevance for accounting history of Amanda Vickery’s study “The Gentleman’s Daughter.” Vickery [1993, pp. -

A VISIT to BARSET the Barsetshire Novels of Anthony Trollope Aideen

93 A VISIT TO BARSET The Barsetshire Novels of Anthony Trollope Aideen E. Brody バー セ ッ トへ の 訪 問 アン トニー ・トロロップのバーセットシャーについての小説 エィ デ ィ ー ン ・ ブ ロ ー デ ィ 19世 紀 の 英 国 作 家 、 ア ン トニ ー ・ ト ロ ロ ッ プ は 架 空 の 州 、 イ ギ リ ス の バ ー セ ッ トシ ャ ー の ・ 人 々 の 生 活 を 描 い た6つ の 小 説 の 作 者 と し て 最:も知 ら れ て い る 。 本 論 文 で は 、 そ の6つ の 小 説 、 そ の 背 景 、 そ し て トロ ロ ッ プ 作 品 の 特 長 に つ い て 語 る。 Although Anthony Trollope was a prolific writer, he is today best remembered for his six books about life in Barsetshire , the fictitious West Country county with its principal town of Barchester which existed so vividly in Trollope's imagination. The novels were The Warden (written in 1855), Barchester Towers (1857), Doctor Thorne (1858), Framley Parsonage (1861), The Small House at Allington (1864) and The Last Chronicle of Barset (1867). Such is Trollope's power of description, both of people and places, that the reader becomes totally caught up in the life of the Barsetshire community, and the title of the final book comes to sound ominous, tolling the knell of parting pleasure. The last chronicle. Oh, no ! Neatly wrapped up and tied together though the series may be, we still want more. The Life of Anthony Trollope Born in London in 1815, Trollope's early life was marked by what might be a peculiarly English defect : coming from a `good' family, educated and titled, (Anthony Trollope's great-great grandson, Sir Anthony Trollope, is the current holder of the title), yet also a financially very embarrassed family, the father still thought it 94 Bul. -

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope Anthony Trollope Autobiography of Anthony Trollope Table of Contents Autobiography of Anthony Trollope.......................................................................................................................1 Anthony Trollope...........................................................................................................................................1 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER I. MY EDUCATION 1815−1834...............................................................................................3 CHAPTER II. MY MOTHER.......................................................................................................................8 CHAPTER III. THE GENERAL POST OFFICE 1834−1841....................................................................12 CHAPTER IV. IRELANDMY FIRST TWO NOVELS 1841−1848........................................................20 CHAPTER V. MY FIRST SUCCESS 1849−1855......................................................................................26 CHAPTER VI. "BARCHESTER TOWERS" AND THE "THREE CLERKS" 1855−1858......................32 CHAPTER VII. "DOCTOR THORNE""THE BERTRAMS""THE WEST INDIES" AND "THE SPANISH MAIN".......................................................................................................................................37 CHAPTER VIII. THE "CORNHILL MAGAZINE" AND "FRAMLEY PARSONAGE".........................41 -

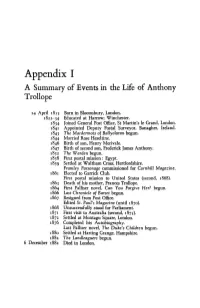

Appendix II Bibliography of Anthony Trollope

Appendix I A Summary of Events in the Life of Anthony Trollope 24 April 1815 Born in Bloomsbury, London. 1822-34 Educated at Harrow; Winchester. 1834 Joined General Post Office, StMartin's le Grand, London. 1841 Appointed Deputy Postal Surveyor, Banagher, Ireland. 1843 The Macdermots of Ballycloran begun. 1844 Married Rose Heseltine. 1846 Birth of son, Henry Merivale. 1847 Birth of second son, Frederick James Anthony. 1852 The Warden begun. 1858 First postal mission: Egypt. 1859 Settled at Waltham Cross, Hertfordshire. Framley Parsonage commissioned for Cornhill Magazine. 1861 Elected to Garrick Club. First postal mission to United States (second, 1868). 1863 Death of his mother, Frances Trollope. 1864 First Palliser novel, Can You Forgive Her? begun. 1866 Last Chronicle of Barset begun. 1867 Resigned from Post Office. Edited St. Paul's Magazine (until187o). 1868 Unsuccessfully stood for Parliament. 1871 First visit to Australia (second, 1875). 1872 Settled at Montagu Square, London. 1876 Completed his Autobiography. Last Palliser novel, The Duke's Children begun. 188o Settled at Harting Grange, Hampshire. 1882 The Landleagu.ers begun. 6 December 1882 Died in London. Appendix II Bibliography of Anthony Trollope (i) MAJOR WORKS The Macdermots of Ballydoran, 3 vols, London: T. C. Newby, 1847 [abridged in one volume, Chapman & Hall's 'New Edition', 1861]. The Kellys and the O'Kellys: or Landlords and Tenants, 3 vols, London: Henry Colburn, 1848. La Vendee: An Historical Romance, 3 vols, London: Colburn, 185o. The Warden, 1 vol, London: Longman, 1855. Barchester Towers, 3 vols, London: Longman, 1857. The Three Clerks: A Novel, 3 vols, London: Bentley, 1858. -

The Novel-Machine Kendrick, Walter

The Novel-Machine Kendrick, Walter Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Kendrick, Walter. The Novel-Machine: The Theory and Fiction of Anthony Trollope. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.68476. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/68476 [ Access provided at 29 Sep 2021 12:38 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. HOPKINS OPEN PUBLISHING ENCORE EDITIONS Walter M. Kendrick The Novel-Machine The Theory and Fiction of Anthony Trollope Open access edition supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. © 2019 Johns Hopkins University Press Published 2019 Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. CC BY-NC-ND ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3402-5 (open access) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3402-4 (open access) ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3400-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3400-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3401-8 (electronic) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3401-6 (electronic) This page supersedes the copyright page included in the original publication of this work. THE NOVEL-MACHINE ��� The Novel-Machine The Theory and Fiction of Anthony Trollope Walter M. Kendrick The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore and London This book was brought to publication with the generous assistance of the Andrew W. -

Based on a Study of His Principal Novels Zatella R. Turner A. B

THE ELEMENT OF- POETICAL JUSTICE IN THE FICTION OF 'ANTHONY TROLLOPE Based On A Study Of His Principal Novels by Zatella R. Turner A. B•• University of Kansas• 1929 Submitted to the Department of_ English and the Faculty o-f the Graduate Schoo1of the Univer- sity of Kansas in partial ful- fillment of. the requirements for the degree of Master of ~. Approved by: This Thesis Is .Aff&ctionately Dedicated to My Parents Whose High Ideals and Untiring Devotion Are a Source of Inspiration to Me. • ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to acknowledge my indebtedness to Pro- fessor John H. Nelson for assistance in the choice of a subject and in the writing of this thesis. May I take this opportunity to express my gratitude to those teachers of the Department of English who have shown an interest in me and an appreciation of my endeavors as a student? . TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I Poetical Justice--vVha. t It Is • • • • • • • • l II Punishment of the Villains or Unworthy Characters • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 5 rrr Reward of the Conspicuously Virtuous Charact.ers • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 23 IV Fate of the Minor Characters •••••••• 39 V Final Treatment of the Especially Outstanding Chsracters •••••••• 63 VI Conclusion ••••••••••••••••• 61 Bibliography • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 70 CHAPTER I POETICAL JUSTICE--WH.AT IT IS In his frank and revealing Autobiography, Anthony Trollope throws much light on his own ideals and endeav- ors ae .a novelist, perhaps, never more clearly than.in the passage which deals with the novelist as a teacher. The passage in question follows: And he [the novelis1f] must teach whether he wish to teach or no •••• if he have a conscience, [heJ must preach his sermons with the same purpose as the clergyman. -

Medical Practitioners in Doctor Thorne and Middlemarch

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 11-1-2009 Uncertain Identity: Medical Practitioners in Doctor Thorne and Middlemarch Denis Illige-Saucier University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Illige-Saucier, Denis, "Uncertain Identity: Medical Practitioners in Doctor Thorne and Middlemarch" (2009). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 301. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/301 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Uncertain Identity: Medical Practitioners in Doctor Thorne and Middlemarch __________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts __________ by Denis Illige-Saucier November 2009 Advisor: Professor Eleanor McNees Author: Denis Illige-Saucier Title: Uncertain Identity: Medical Practitioners in Doctor Thorne and Middlemarch Advisor: Eleanor McNees Degree Date: November 2009 ABSTRACT The medical practitioners who play leading roles in the novels Middlemarch by George Eliot and Doctor Thorne by Anthony Trollope are examples of a new breed of professional medical men that emerged during the middle of the nineteenth century in England. The new class of general practitioners held licenses from the old hierarchical system of physicians, surgeons, and apothecaries, but they were the driving force in favor of reform and professionalization in medicine. -

Barchester Towers

THE JOURNAL OF THE Number 113 ~ Summer 2019 Trollope on Trains Reverend William Marshall EDITORIAL ~ 1 Contents Editorial Number 113 ~ Summer 2019 FEATURES t is a rare pleasure for an editor to receive an unsolicited 2 Trollope on Trains manuscript that provides a readable yet erudite article that By the Reverend William Marshall, who lives in Ireland and has been can be shared with readers with scarcely a change. Such was fascinated by the use of trains in Trollope’s writing both as locations for I scenes and as plot devices to drive the narrative. my experience on first reading William Marshall’s summary of the appearance of trains in Trollope’s novels. The article reveals the great 7 2019 Biennial Dinner: Lincoln’s Inn and Phineas use Trollope made of this new form of transport across a broad range Finn of his works and how this may also reveal something about Victorian By Michael Williamson, a former Chairman of the Society, who describes Society and culture. the connections between Anthony Trollope, his character Phineas Finn, The recent dinner held by the Society for members and guests and Lincoln’s Inn, where the Society held its recent dinner event for members and guests. at Lincoln’s Inn took as its theme Phineas Finn, marking the 150th anniversary of the novel’s publication. It seems fitting therefore to look 16 Madeline Neroni back at the connections between Trollope, in particular through his By Mark Green who puts forward a controversial theory about the father whose law chambers were at the Inn, and the venue. -

The Journal of The

THE JOURNAL OF THE Number 97 ~ Winter 2013-14 Trollope and Ireland Haruno Kayama Watanabe EDITORIAL ~ 1 Contents Editorial Number 97 ~ Winter 2013-14 his has been an eventful few months. At the 26th Annual FEATURES Lecture Alex Preston, novelist and columnist, discussed the influences of The Way We Live Now on current authors and on 2 Trollope and Ireland: An Eye For An Eye T Haruno Kayama Watanabe his own debut novel This Bleeding City. Readers can appreciate an An Associate Professor at Atomi University in Tokyo, Haruno Kayama abridged transcript within these pages, although they will be unable Watanabe looks at the significant role that Ireland played in Trollope’s to savour the delicious and substantial canapes and drinks enjoyed by life. many of us, nor benefit from the post Trollopian discussion. During the summer some of us increased our learning at the 9 A Tale of Three Sons Dr Nigel Starck Wansfell Course led by Howard Gregg, or laughed at the play- Nigel Starck explores how two sons of Charles Dickens and a son of reading of Henry Ong’s adaptation of Rachel Ray, both of which will Anthony Trollope became friends in Australia. be summarized in later issues. The Trollope International Conference in Drumsna was also attended by some of us, from which Haruna 13 Bookplates and Labels in Anthony Trollope’s Library Bryan Welch Watanabe’s paper is reproduced below. We are also looking forward Bryan Welsh examines how Anthony Trollope arranged and catalogued to visiting Casewick Manor, home of the Trollope baronetcy, in June his library according to the historic system of ‘fixed shelf’ locations. -

Barchester Towers : the Chronicles of Barsetshire Pdf, Epub, Ebook

BARCHESTER TOWERS : THE CHRONICLES OF BARSETSHIRE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Anthony Trollope | 528 pages | 01 Dec 2014 | Oxford University Press | 9780199665860 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom Barchester Towers : The Chronicles of Barsetshire PDF Book The first was a very earnest book about goodness and conscience; the second is a book about manners, and wickeder entirely. While Mary appears to have no fortune, she is actually the illegitimate niece of the millionaire Sir Roger Scatcherd, a fact known only to Doctor Thorne. An Autobiography. Get the IMDb app. The plot of this book deals with the leading clergy of the Barchester city. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Her interference to veto the reappointment of the universally popular Mr Septimus Harding protagonist of Trollope's earlier novel, The Warden as warden of Hiram's Hospital is not well received, even though she gives the position to a needy clergyman, Mr Quiverful, with 14 children to support. Harding, a clergyman of … More. Book 5. Doctor Thorne by Anthony Trollope. Proudie speaking to Archdeacon Grantly at their first meeting. Maggie Jones. Donald Pleasence was cast at short notice, after the death of the actor who was first cast in the role. Oxford: Oxford University Press. The Chronicles follow the intrigues of ambition and love in the cathedral town of Barchester. Heck even if you're not a fan of Reacher, it's still an excellent series and well worth reading. Although the stories follow each other and often reference events in earlier titles, each novel is complete in itself. The Warden. Harding and his daughter, Eleanor, adding to his cast of characters that oily symbol of progress, Mr. -

A Discussion of Contracts and Domestic Arrangements, the Carol Weisbrod University of Connecticut School of Law

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Faculty Articles and Papers School of Law 1994 Way We Live Now: A Discussion of Contracts and Domestic Arrangements, The Carol Weisbrod University of Connecticut School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_papers Part of the Contracts Commons, Family Law Commons, and the Law and Economics Commons Recommended Citation Weisbrod, Carol, "Way We Live Now: A Discussion of Contracts and Domestic Arrangements, The" (1994). Faculty Articles and Papers. 89. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_papers/89 +(,121/,1( Citation: 1994 Utah L. Rev. 777 1994 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Mon Aug 15 18:31:14 2016 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=0042-1448 The Way We Live Now: A Discussion of Contracts and Domestic Arrangements* Carol Weisbrod* 'Law means so pitifully little to life. Life is so terrifyingly dependent on the law." Karl N. Llewellyn What Price Contract?-An Essay in Perspective I. INTRODUCTION There is currently great interest in the subject of contracts and the family, particularly, although not exclusively, among those who apply principles of law and economics to marriage contracts.' * © 1994 by Carol Weisbrod. ** Ellen Ash Peters Professor of Law, University of Connecticut School of Law.