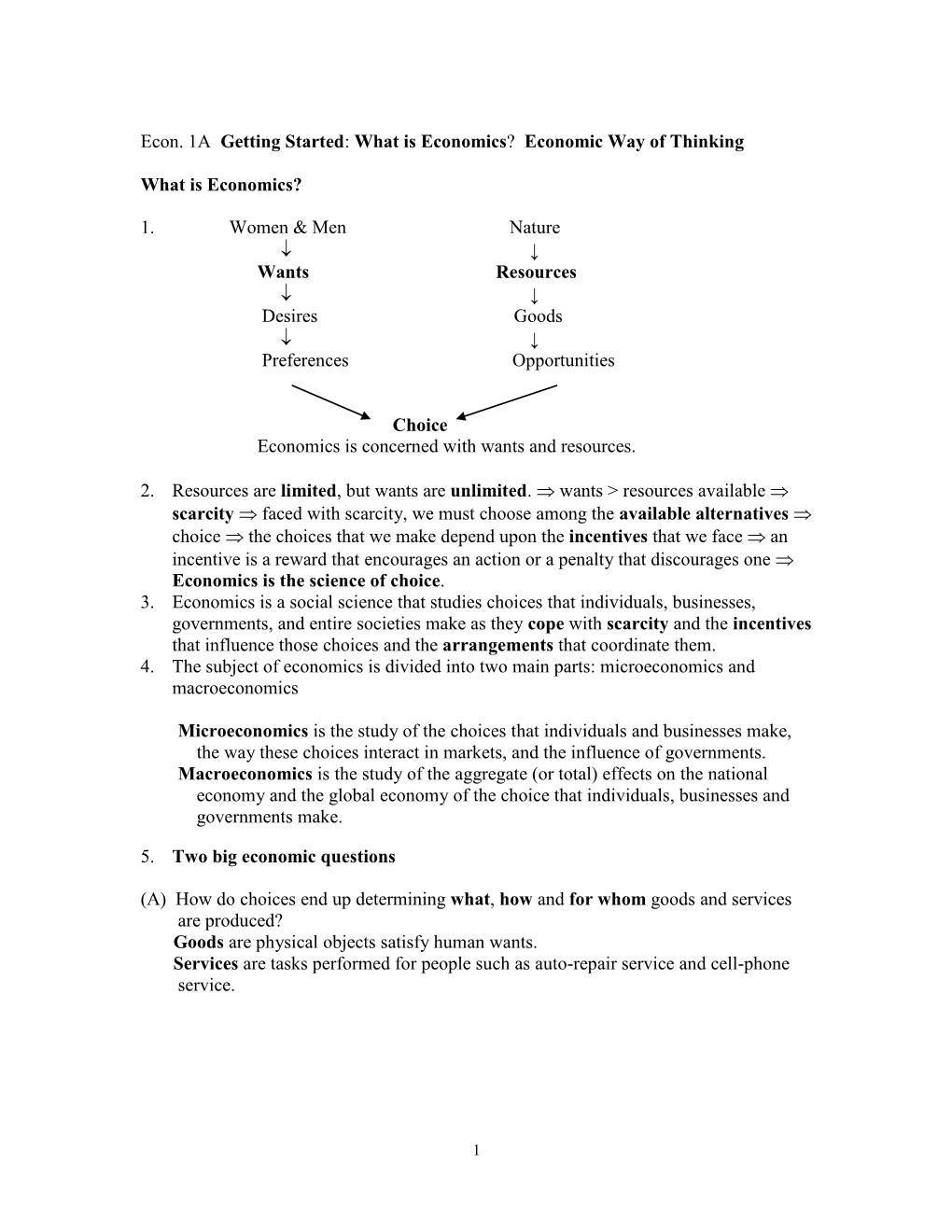

Econ. 1A Getting Started: What Is Economics? Economic Way of Thinking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest: International Trends and Determinants

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF SAN FRANCISCO WORKING PAPER SERIES Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest: International Trends and Determinants Kathryn Holston and Thomas Laubach Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System John C. Williams Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco December 2016 Working Paper 2016-11 http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/working-papers/wp2016-11.pdf Suggested citation: Holston, Kathryn, Thomas Laubach, John C. Williams. 2016. “Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest: International Trends and Determinants.” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Paper 2016-11. http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/working- papers/wp2016-11.pdf The views in this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest: International Trends and Determinants∗ Kathryn Holston Thomas Laubach John C. Williams December 15, 2016 Abstract U.S. estimates of the natural rate of interest { the real short-term interest rate that would prevail absent transitory disturbances { have declined dramatically since the start of the global financial crisis. For example, estimates using the Laubach-Williams (2003) model indicate the natural rate in the United States fell to close to zero during the crisis and has remained there into 2016. Explanations for this decline include shifts in demographics, a slowdown in trend productivity growth, and global factors affecting real interest rates. This paper applies the Laubach-Williams methodology to the United States and three other advanced economies { Canada, the Euro Area, and the United Kingdom. -

Inflation, Income Taxes, and the Rate of Interest: a Theoretical Analysis

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Inflation, Tax Rules, and Capital Formation Volume Author/Editor: Martin Feldstein Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-24085-1 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/feld83-1 Publication Date: 1983 Chapter Title: Inflation, Income Taxes, and the Rate of Interest: A Theoretical Analysis Chapter Author: Martin Feldstein Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c11328 Chapter pages in book: (p. 28 - 43) Inflation, Income Taxes, and the Rate of Interest: A Theoretical Analysis Income taxes are a central feature of economic life but not of the growth models that we use to study the long-run effects of monetary and fiscal policies. The taxes in current monetary growth models are lump sum transfers that alter disposable income but do not directly affect factor rewards or the cost of capital. In contrast, the actual personal and corporate income taxes do influence the cost of capital to firms and the net rate of return to savers. The existence of such taxes also in general changes the effect of inflation on the rate of interest and on the process of capital accumulation.1 The current paper presents a neoclassical monetary growth model in which the influence of such taxes can be studied. The model is then used in sections 3.2 and 3.3 to study the effect of inflation on the capital intensity of the economy. James Tobin's (1955, 1965) early result that inflation increases capital intensity appears as a possible special case. -

Interest Rates and Expected Inflation: a Selective Summary of Recent Research

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Explorations in Economic Research, Volume 3, number 3 Volume Author/Editor: NBER Volume Publisher: NBER Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/sarg76-1 Publication Date: 1976 Chapter Title: Interest Rates and Expected Inflation: A Selective Summary of Recent Research Chapter Author: Thomas J. Sargent Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c9082 Chapter pages in book: (p. 1 - 23) 1 THOMAS J. SARGENT University of Minnesota Interest Rates and Expected Inflation: A Selective Summary of Recent Research ABSTRACT: This paper summarizes the macroeconomics underlying Irving Fisher's theory about tile impact of expected inflation on nomi nal interest rates. Two sets of restrictions on a standard macroeconomic model are considered, each of which is sufficient to iniplv Fisher's theory. The first is a set of restrictions on the slopes of the IS and LM curves, while the second is a restriction on the way expectations are formed. Selected recent empirical work is also reviewed, and its implications for the effect of inflation on interest rates and other macroeconomic issues are discussed. INTRODUCTION This article is designed to pull together and summarize recent work by a few others and myself on the relationship between nominal interest rates and expected inflation.' The topic has received much attention in recent years, no doubt as a consequence of the high inflation rates and high interest rates experienced by Western economies since the mid-1960s. NOTE: In this paper I Summarize the results of research 1 conducted as part of the National Bureaus study of the effects of inflation, for which financing has been provided by a grait from the American life Insurance Association Heiptul coinrnents on earlier eriiins of 'his p,irx'r serv marIe ti PhillipCagan arid l)y the mnibrirs Ut the stall reading Committee: Michael R. -

ADM-505 How to Determine Interest Rates

How to Determine Pre- & Post- Judgment Interest Rates in 2021 1. Is there a contract that sets the interest rate? If not, go to #2. 2. Is there a statute other than AS 09.30.070 that sets the interest rate? 1 If not, go to #3. 3. When did the cause of action accrue? 2 a. Before August 7, 1997: Both the pre- & post- judgment interest rates are 10.5%3 b. On or After August 7, 1997: Both pre- & post- judgment interest rates will be the interest rate for the year in which the judgment is entered.4 For judgments entered in 2021, this rate is 3.25%.5 Note: After the interest rate on a particular judgment is established, it does not later change, even though the interest rate changes. For example: The post-judgment interest rate on a judgment entered in 2001 is 9%. That rate will stay 9% until the judgment is paid. It is not affected by the fact that new judgments entered in 2021 will have a 3.25% interest rate. 1 Examples of other statutes that set interest rates: • AS 25.27.025 – child support arrearages • AS 06.05.473(h) – claims upon liquidation of a state bank • AS 09.55.440(a) – compensation for property taken in eminent domain proceeding • AS 13.16.475(d) – claims against decedent’s estate 2 Accrue. In general, a cause of action “accrues” when a suit may be maintained thereon, that is, when sufficient events have occurred to support a valid lawsuit (for example, when injury or damage occurs or when a contract is breached). -

Fact Sheet on Interest Rate Restrictions

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation FACT SHEET Interest Rate Restrictions The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) published a final rule to revise its regulations relating to interest rate restrictions on banks that are less than well capitalized. PROMOTES FLEXIBILITY AND RESPONSIVENESS ACROSS ECONOMIC CYCLES – The final rule promotes flexibility for institutions subject to the interest rate restrictions and ensures that those institutions will be able to compete for deposits regardless of the interest rate environment. • The final rule defines the “National Rate Cap” as the higher of (1) the national rate plus 75 basis points; or (2) for maturity deposits, 120 percent of the current yield on similar maturity U.S. Treasury obligations and, for nonmaturity deposits, the federal funds rate, plus 75 basis points. • By establishing two methods for calculating the national rate cap, the FDIC ensures that deposit interest rate caps are durable under both high-rate or rising-rate environments and low-rate or falling-rate environments. MORE COMPREHENSIVE NATIONAL RATE – The final rule defines the National Rate to include credit union rates for the first time. • “National Rate” is defined as the weighted average of rates paid by all IDIs and credit unions on a given deposit product, for which data are available, where the weights are each institution’s market share of domestic deposits. PROMOTES TRANSPARENCY – The final rule calculates the National Rate Cap based on similar maturity U.S. Treasury obligations and the federal funds rate, which are both publicly available, and thus, represent a more transparent calculation for bankers and the public. REDUCES REGULATORY BURDEN – The final rule provides a new simplified process, as opposed to the current two-step process, for institutions that seek to offer a competitive rate when the prevailing rate in an institution’s local market area exceeds the national rate cap. -

The-Great-Depression-Glossary.Pdf

The Great Depression | Glossary of Terms Glossary of Terms Balanced budget – Government revenues equal expenditures on an annual basis. (Lesson 5) Bank failure – When a bank’s liabilities (mainly deposits) exceed the value of its assets. (Lesson 3) Bank panic – When a bank run begins at one bank and spreads to others, causing people to lose confidence in banks. (Lesson 3) Bank reserves – The sum of cash that banks hold in their vaults and the deposits they maintain with Federal Reserve banks. (Lesson 3) Bank run – When many depositors rush to the bank to withdraw their money at the same time. (Lesson 3) Bank suspensions – Comprises all banks closed to the public, either temporarily or permanently, by supervisory authorities or by the banks’ boards of directors because of financial difficulties. Banks that close under a special holiday declaration and remained closed only during the designated holiday are not counted as suspensions. (Lesson 4) Banks – Businesses that accept deposits and make loans. (Lesson 2) Budget deficit – When government expenditures exceed revenues. (Lesson 4) Budget surplus – When government revenues exceed expenditures. (Lesson 4) Consumer confidence – The relationship between how consumers feel about the economy and their spending and saving decisions. (Lesson 5) Consumer Price Index (CPI) – A measure of the prices paid by urban consumers for a market basket of consumer goods and services. (Lesson 1) Deflation – A general downward movement of prices for goods and services in an economy. (Lessons 1, 3 and 6) Depression – A very severe recession; a period of severely declining economic activity spread across the economy (not limited to particular sectors or regions) normally visible in a decline in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, wholesale-retail credit and the loss of overall confidence in the economy. -

Deflation: Economic Significance, Current Risk, and Policy Responses

Deflation: Economic Significance, Current Risk, and Policy Responses Craig K. Elwell Specialist in Macroeconomic Policy August 30, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R40512 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Deflation: Economic Significance, Current Risk, and Policy Responses Summary Despite the severity of the recent financial crisis and recession, the U.S. economy has so far avoided falling into a deflationary spiral. Since mid-2009, the economy has been on a path of economic recovery. However, the pace of economic growth during the recovery has been relatively slow, and major economic weaknesses persist. In this economic environment, the risk of deflation remains significant and could delay sustained economic recovery. Deflation is a persistent decline in the overall level of prices. It is not unusual for prices to fall in a particular sector because of rising productivity, falling costs, or weak demand relative to the wider economy. In contrast, deflation occurs when price declines are so widespread and sustained that they cause a broad-based price index, such as the Consumer Price Index (CPI), to decline for several quarters. Such a continuous decline in the price level is more troublesome, because in a weak or contracting economy it can lead to a damaging self-reinforcing downward spiral of prices and economic activity. However, there are also examples of relatively benign deflations when economic activity expanded despite a falling price level. For instance, from 1880 through 1896, the U.S. price level fell about 30%, but this coincided with a period of strong economic growth. -

The Essential JOHN STUART MILL the Essential DAVID HUME

The Essential JOHN STUART MILL The Essential DAVID HUME DAVID The Essential by Sandra J. Peart Copyright © 2021 by the Fraser Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. The author of this publication has worked independently and opinions expressed by him are, therefore, his own, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Fraser Institute or its supporters, directors, or staff. This publication in no way implies that the Fraser Institute, its directors, or staff are in favour of, or oppose the passage of, any bill; or that they support or oppose any particular political party or candidate. Printed and bound in Canada Cover design and artwork Bill C. Ray ISBN 978-0-88975-616-8 Contents Introduction: Who Was John Stuart Mill? / 1 1. Liberty: Why, for Whom, and How Much? / 9 2. Freedom of Expression: Learning, Bias, and Tolerance / 21 3. Utilitarianism: Happiness, Pleasure, and Public Policy / 31 4. Mill’s Feminism: Marriage, Property, and the Labour Market / 41 5. Production and Distribution / 49 6. Mill on Property / 59 7. Mill on Socialism, Capitalism, and Competition / 71 8. Mill’s Considerations on Representative Government / 81 Concluding Thoughts: Lessons from Mill’s Radical Reformism / 91 Suggestions for Further Reading / 93 Publishing information / 99 About the author / 100 Publisher’s acknowledgments / 100 Supporting the Fraser Institute / 101 Purpose, funding, and independence / 101 About the Fraser Institute / 102 Editorial Advisory Board / 103 Fraser Institute d www.fraserinstitute.org Introduction: Who Was John Stuart Mill? I have thought that in an age in which education, and its improvement, are the subject of more, if not of profounder study than at any former period of English history, it may be useful that there should be some record of an education which was unusual and remarkable. -

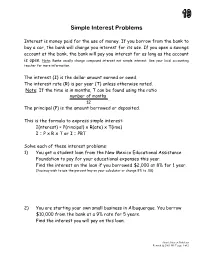

Simple Interest Problems

Simple Interest Problems Interest is money paid for the use of money. If you borrow from the bank to buy a car, the bank will charge you interest for its use. If you open a savings account at the bank, the bank will pay you interest for as long as the account is open. Note: Banks usually charge compound interest not simple interest. See your local accounting teacher for more information. The interest (I) is the dollar amount earned or owed. The interest rate (R) is per year (T) unless otherwise noted. Note: If the time is in months, T can be found using the ratio number of months . 12 The principal (P) is the amount borrowed or deposited. This is the formula to express simple interest: I(nterest) = P(rincipal) x R(ate) x T(ime) I = P x R x T or I = PRT Solve each of these interest problems: 1) You get a student loan from the New Mexico Educational Assistance Foundation to pay for your educational expenses this year. Find the interest on the loan if you borrowed $2,000 at 8% for 1 year. (You may wish to use the percent key on your calculator or change 8% to .08) 2) You are starting your own small business in Albuquerque. You borrow $10,000 from the bank at a 9% rate for 5 years. Find the interest you will pay on this loan. Simple Interest Problems Revised @ 2009 MLC page 1 of 2 3) You are tired at the end of the term and decide to borrow $500 to go on a trip to Whatever Land. -

Interest Rate Expectations and the Slope of the Money Market Yield Curve

Interest Rate Expectations and the Slope of the Money Market Yield Curve Timothy Cook and Thomas Hahn l What determines the relationship between yield This paper surveys the recent literature on the and maturity (the yield curve) in the money market? determinants of the yield curve. It begins by review- A resurgence of interest in this question in recent ing the expectations theory and recent empirical tests years has resulted in a substantial body of new of the theory. It discusses two general explanations research. The focus of much of the research has been for the lack of support for the theory from these tests. on tests of the “expectations theory.” According to Finally, the paper discusses in more detail the the theory, changes in the slope of the yield curve behavior of market participants that might influence should depend on interest rate expectations: the more the yield curve, and the role that monetary policy market participants expect rates to rise, the more might play in explaining this behavior. positive should be the slope of the current yield curve. The expectations theory suggests that vari- I. ation in the slope of the yield curve should be THE EXPECTATIONS THEORY systematically related to the subsequent movement Concepts in interest rates. Much of the recent research has focused on whether this prediction of the theory is Two concepts central to the tests of the expecta- supported by the data. A surprising finding is that tions theory reviewed below are the “forward rate parts of the yield curve have been useful in forecasting premium” and the “term premium.” Suppose an in- interest rates while other parts have not. -

What Fiscal Policy Is Effective at Zero Interest Rates?

Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports What Fiscal Policy Is Effective at Zero Interest Rates? Gauti B. Eggertsson Staff Report no. 402 November 2009 This paper presents preliminary findings and is being distributed to economists and other interested readers solely to stimulate discussion and elicit comments. The views expressed in the paper are those of the author and are not necessarily reflective of views at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author. What Fiscal Policy Is Effective at Zero Interest Rates? Gauti B. Eggertsson Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 402 November 2009 JEL classification: E52 Abstract Tax cuts can deepen a recession if the short-term nominal interest rate is zero, according to a standard New Keynesian business cycle model. An example of a contractionary tax cut is a reduction in taxes on wages. This tax cut deepens a recession because it increases deflationary pressures. Another example is a cut in capital taxes. This tax cut deepens a recession because it encourages people to save instead of spend at a time when more spending is needed. Fiscal policies aimed directly at stimulating aggregate demand work better. These policies include 1) a temporary increase in government spending; and 2) tax cuts aimed directly at stimulating aggregate demand rather than aggregate supply, such as an investment tax credit or a cut in sales taxes. The results are specific to an environment in which the interest rate is close to zero, as observed in large parts of the world today. -

Historically Illustrating the Shift to Neoliberalism in the U.S. Home Mortgage Market

societies Essay Historically Illustrating the Shift to Neoliberalism in the U.S. Home Mortgage Market Ivis García City and Metropolitan Planning Department, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 60608, USA; [email protected] Received: 8 October 2018; Accepted: 12 January 2019; Published: 18 January 2019 Abstract: This article takes a long view of the U.S. housing market; from its inception as locally owned and operated Building Societies, through one of the first major U.S. housing crises in the early 1930s, as well as through the prosperous and surprisingly stable post-WWII era the so-called “Long Boom” during Keynesianism. As labor shortages became more severe, accompanied by stagflation and the simultaneous urban, fiscal, and oil crises of the late 60s and early 70s, key sectors of the U.S. economy rallied to dismantle established Keynesian policies. While the new policies associated with laissez–faire economic liberalism certainly aided in the mobility of capital, the overall economy as a result of this neoliberal turn became increasingly unstable and inequitable. This article seeks to add knowledge to the neoliberalism theory. The author concludes, based on a historical case study of the Savings and Loans industry, that neoliberalism was not a deterministic overthrow of neoliberal ideologues but a haphazard response to the contradictions of Keynesian logic. It is only from a historical approach that we may be able to understand the current housing crisis, foster policy innovation, and allow for institutional change within the U.S. mortgage market sector. Keywords: banking; financial institutions; industry; mortgages 1. Introduction The effect of neoliberalism in the field of housing studies has gained considerable attention among scholars [1–4].