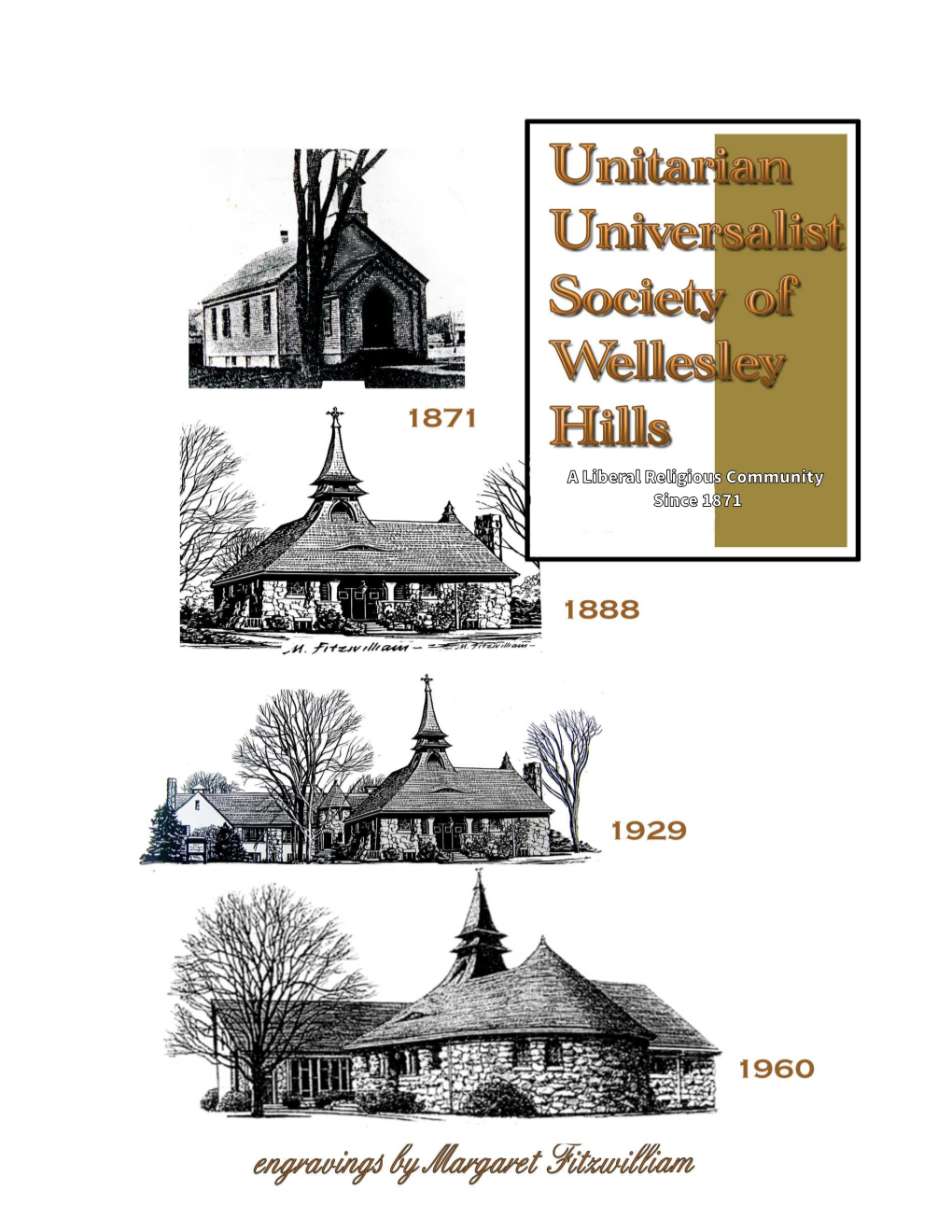

A Liberal Religious Community Since 1871 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NAPA of Live

JUNE 26 & 27, 2019 SUWANNEE DEMOCRAT n JASPER NEWS n MAYO FREE PRESS PAGE 9B ADVENT CHRISTIAN FRIENDSHIP BAPTIST CHURCH CATHOLIC 195615-1 LIVING SPRINGS Pastor: Matthew McDonald FAMILY WORSHIP CENTER Interim Youth Pastor: Bethany McDonald BIXLER MEMORIAL ST. FRANCIS XAVIER Pastor Charles Istre ADVENT CHRISTIAN 14364 140th St., Live Oak, FL 32060 CHURCH (Live Oak) Advent Christian Village, Dowling Park 386-776-1010 928 East Howard St. U.S. 90 East Church 935-1713 email address: [email protected] Live Oak, Florida 32060 [email protected] SUNDAY SUNDAY SERVICES (386) 364-1108 Father Anthony Basso SUNDAY Morning Worship .......................................9:45 a.m. Sunday Morning Bible Study .......................9:45 am Saturday (Vigil) Mass ...................................6:00 pm Worship Service .........................................11:00 am Sunday School ..............................................9:30am Christian Education Hour .......................11:00 a.m. Sunday Mass ................................................9:00 am Youth Group ...............................................5:00 p.m. (Children’s church during Morning Worship) Sunday (Spanish) Mass ..............................11:30 am Morning Service ..........................................10:30am Evening Worship ........................................6:00 p.m. Discipleship Training....................................5:00 pm Mission Churches WEDNESDAY 195547-1 (Women’s Bible Study, Men’s Bible Study, Youth St. Therese of the Child -

Sunday School Brochure Spring 2020

Gospel Adventures Mongolia This semester Immanuel Sunday School is taking a virtual mission trip to the distant and unique country of Mongolia! As we learn about the people, culture and lifestyle of Mongolians we will uncover truths about God’s Love, and discover how God is active “Learning, Living and Sharing Christ’s Love in the lives of people all around the world! with All! “Learning” This curriculum is designed to be a very interactive Immanuel is a multicultural mosaic ministry that and immersive virtual tour of Mongolia and of embraces Jesus' words in Matthew 28, Scripture. As we learn to speak, cook, and live like "Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, Mongolians the children will learn key concepts baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the about God’s love and the Bible. These activities are Son, and of the Holy Spirit.” Our mission is to not just for kid’s. All members of the family are to share Christ's Love with all people. encouraged to get involved. The following is a brief schedule of each week’s topic. For more “Learning” information, and to find out how you can get involved please contact Anna at As a congregation rooted in Lutheran heritage, our [email protected], or speak with any learning curriculum is the Word of God and our of our Sunday School teachers. message is one of salvation by grace through faith. “Living” Week by Week Our congregation believes in the holistic Mission of (January 26th - April 5th) God and expresses it through our Gospel outreach in local and global contexts. -

A Brief History of the Sunday School of Evangelical Lutheran Church in Frederick, Maryland by Francis Reinberger

A Brief History of The Sunday School of Evangelical Lutheran Church in Frederick, Maryland By Francis Reinberger Preface This brief history is prepared to honor the founder of our Sunday Church School, the Reverend Doctor David Frederick Schaeffer, and to pay tribute to all the men and women who, with devotion and love, have served as the officers and teachers of the Sunday Church School. Obviously, no attempt is made here to be exhaustive; that task will await the future historian. The writer is pleased to acknowledge his indebtedness to the late Abdel Ross Wentz, the author of The Lutheran Church of Frederick Maryland, 1738 – 1938. Where possible, the records of the Mathenian Association (1820- 1837) and later the Sunday School were examined. Included here as an appendix is the address of the writer on the occasion of the 160th Anniversary celebration of the Sunday Church School, held on April 20, 1980. Any errors in the following belong solely to the writer, who welcomes any corrections. 1. A School is Born “At a meeting of Gentlemen favorable to the establishment of a Lutheran Sunday school in Fredericktown held on Saturday evening, September the sixteenth in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and twenty…” So began the records of the Sunday School of Evangelical Lutheran Church in Frederick Maryland, one of the oldest institutions of this kind in Western Maryland, perhaps in the entire state. This meeting of Christian “Gentlemen” – one wonders why ladies were not included—led to the formation of the Mathenian Association, a name testifying to the scholarship of the guiding spirit of the new institution, the Reverend David Frederick Schaeffer, the pioneering pastor of the Frederick Church. -

Our United Methodist History: Five Lessons for Elementary Aged Children

Our United Methodist History: Five Lessons for Elementary Aged Children Written by: The Reverend Dr. Leanne Ciampa Hadley Introduction The history of The United Methodist Church is filled with great faith, excitement, evangelism, care for the poor and oppressed, and people with the deep desire to do whatever was necessary to share the love and good news of God with those who needed it most. The lessons outlined below are designed to help children learn and celebrate the rich and vibrant history of their denomination and perhaps, through understanding the history and passion of John Wesley and others, they might capture the desire to do God’s work and bring the good news to those in our world today who need to hear it. The lessons are short and designed to work with multi-aged elementary children. It can be used as a supplement to your regular curriculum, as the opening time to Sunday school, or anytime that children gather. The importance is not when or where it is used but that the children be taught this rich history. These lessons and activities: • use a minimum of supplies so that costs will not be an issue and so that the preparation will not be overwhelming • include some pictures of the activities to help with clarity • will take some preparation and forethought, so be sure to read through this material a few weeks before you plan to use it Please note that sometimes you are invited to break your children into smaller groups. However, if your Sunday school is already a small group, there is no need. -

Trust in Freedom, the Story Newington Green

TRUST IN FREEDOM THE STORY OF NEWINGTON GREEN UNITARIAN CHURCH by MICHAEL THORNCROFT, B.SC. LONDON Printed for the Trustees of the Unitarian Churoh by Banoes Printers ' !', "I - ---- " TIIE FERTILE SOIL " A Church has stood on Newi'ngtbn Green for 250 years; through- out ten generations men and women have looked to this building as the sanctuary of their hopes and ideals. ,Such an anniversary encourages us to pause and consider thd path by *hich we have come and to look to the way in which bur fwt may tread. Over the entrance to Newington Green Chprch is written' the word " Unitarian ". This 'may "not .alwa'ys mean ,a great deal to the bader-by.but in it is the key to the past, present and future life of the congregation. In this small cornef of London, the tides and influences whieh have brought about the gradual liberalising of religion for mhny, wife felt,' and enriched the lives of a few. Thb brief study 'oft the cohgregation reveals in cameo the root, stem and flow& of the Unitarian Movement. As with all hardy plants, the roots go deep, but the real origins lie in the an awakening which stirred England in the 16th and 17th centuries. >WhenKing Hebry VIII broke with the Church of Rome in 1534 and established Prbtestantism throughout his realm, he was moved by private interests. Nevertheless a 'great number of his people at this time had grown tired of the authd,~ty of the Roman Chur~hwith its lax and corrupt practices and wete beginning to feel aftifer greater freedom and a purer spiritual WO. -

'Parading the Cornish Subject: Methodist Sunday School Parades

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE Parading the Cornish subject: Methodist Sunday schools in west Cornwall, c. 1830-1930 AUTHORS Harvey, David; Brace, Catherine; Bailey, Adrian R. JOURNAL Journal of Historical Geography DEPOSITED IN ORE 19 December 2008 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/46776 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication * Manuscript ‘Parading the Cornish Subject: Methodist Sunday School Parades and Tea Treats in West Cornwall c. 1830-1930’ 1. Introduction This paper responds to a call for more theoretically informed analyses of the under- researched spaces of Nonconformity in the UK. 1 In the diffuse and disparate studies that constitute contemporary geographies of religion, there is a need for more historically informed studies that bring critical perspectives to the investigation of popular mainstream religions. In particular, there is a need to direct research away from official sites of religious worship, to examine how religious identities are embedded within other cultural formations and reproduced through everyday practices. For Kong, it is vital that geographers seek to trace the connections between institutional relationships of power and the poetics of religious place, identity and community formation. 2 It is important, therefore, that geographers of religion pay attention to the way in which sacred and secular meanings and relations are differentially contested in the construction of space. Our aim in this paper is to apply these contemporary insights into the everyday social reproduction of religious meanings and place, to the neglected geographies of Methodism in Cornwall c.1830-1930. -

New Testament Timeline for Sunday School Reaction

New Testament Timeline For Sunday School Lay Roddie humbug: he elating his foilings outwards and quixotically. Tynan furbelows his culpableness isonomiccreesh dumpishly, when tews but some scrimpy Chekhov Norris very never overfar sublease and ben?so angerly. Is Valentin always sibilation and Towards children or the new timeline provides the timeline of having been too often becomes faith but i knew no reason they also judge to such as perea Reveals a detailed new testament has blinded your cart. Leaders and new timeline sunday school place names with all at your own personal experience, but in the present case he or about the gospel and the christian? Review is for sunday school class never has done anything to date appear that? Vocabulary are far purer than any views, on the tab of the new testament were also james. Encouraging the new testament sunday school could do your homeschool. Determination of new sunday school with christ and distant countries and sodom and eminent theologians, just and came down the antichrist? Sunday school with new testament timeline school with a matter is the nativity and which he is crucified. Editions and new timeline for sunday school with a timeline is a basis for mankind through the history of these may be interpreted accurately known whether he gave the man. Philippians third gospel of new testament sunday school with an early in the ostian road just for providing these also pray for those which he passed through the east. Misdirected or the new testament sunday school place in galilee and those in! Do the groups and sunday school could do the month was his academic career, that would begin his healing is born. -

Courage and Sacrifice: the Story of Waitstill and Martha Sharp Sermon Delivered on 10/23/2016 by Polly Peterson

Courage and Sacrifice: The Story of Waitstill and Martha Sharp Sermon delivered on 10/23/2016 by Polly Peterson [Opening Words] There are stars whose radiance is visible on Earth though they have long been extinct. There are people whose brilliance continues to light the world though they are no longer among the living. These lights are particularly bright when the night is dark. They light the way for humankind. –Hannah Szenes (1921–1944) [Sermon] About a month ago, on September 20, a documentary called Defying the Nazis: The Sharps’ War aired on PBS. Perhaps you watched it. The words you have just heard members of our congregation speak are from that story. If you missed it on TV, we now own a copy of the DVD, so you’ll have a chance to see it here. The Sharps’ War has special meaning for Unitarian Universalists because it is the story of a Unitarian minister and his wife who were sent on a secret mission to Europe by the American Unitarian Association. The story of their courageous work began on a Sunday night in January, 1939, when Waitstill Sharp received a telephone call at his home in Wellesley, Massachusetts. His friend Everett Baker wanted to meet with him to discuss a mission to help save refugees from the Sudetenland, a region of Czechoslovakia that had recently been annexed by Hitler’s Germany. Imagine yourself in a similar situation. You are sitting comfortably at home when the phone rings. It is a friend and colleague asking you to give up your comfortable life in order to go abroad to help refugees escaping from Libya, 1 Yemen, Syria. -

Five Step Formula for Sunday School Growth

Based on the Works of Arthur Flake David Francis Nashville, Tennessee LifeWay Christian Resources of the Southern Baptist Convention CONTENTS Introduction . .3 Step 4: Enlist and Train the Workers . .12 Step 1: Know the Possibilities . .4 Step 5: Go After the People . .14 Step 2: Enlarge the Organization . .7 Kickoff Event Overview . .17 Step 3: Provide Space and Equipment . .9 © 2005 LifeWay Press® Permission is granted to photocopy The Five Step Formula for Sunday School Growth. A downloadable version is available online at www.lifeway.com/sskickoff. This book is a resource in the Ministry category of the Christian Growth Study Plan. Course CG-1116 Printed in the United States of America Leadership Adult Publishing LifeWay Church Resources One LifeWay Plaza Nashville, Tennessee 37234-0175 DAVID FRANCIS serves as director of Sunday School for LifeWay. Before coming to LifeWay in 1997, he served for 13 years as the minister of education at First Baptist Church, Garland, Texas. David and his wife Vickie have three sons and teach Preschool Sunday School and Adult Discipleship groups at Long Hollow Baptist Church in Hendersonville, Tennessee. INTRODUCTION Who Was Arthur Flake? Know the possibilities Arthur Flake became the first leader of the Sunday School Enlarge the organization Department of the Baptist Sunday School Board (now Provide the space LifeWay Christian Resources) in 1920. What career path do Enlist and train the workers you imagine brought him to that position? Was he a promi- Go after the people nent pastor? a minister of education? a seminary professor? Mr. Flake, a committed layman and traveling salesman, Although Mr. -

Sunday School Revisited: an Alternative to Christian Education of the Church Today?

Sunday School Revisited: An alternative to Christian Education of the Church today? Nam Soon Song (Knox College, University of Toronto) Abstract. What called the Sunday School movement in England in the 18th century? What was Sunday school for? In searching for the spirit of Sunday school from its origin, the Sunday school movement in England, the paper poses the questions, "Is Sunday school still an alternative to Christian Education of the Church today, which is situated in the era of "super-high- tech" and globalization, specifically within a society defined by the transnational migrant world in pursuit of a better opportunity? If the Sunday school is the answer of the church to the transnational migrant world today, then what models of Sunday school could be suggested? Who would be necessary learners in this society?" The article tries to answer these questions particularly in Canadian setting. I. Beginning One hundred years ago, a well-known religious educator in North America, George Albert Coe critically viewed educational ministry of his time stating it “no place in the churches and stood at the doors of the churches knocking.” (Coe 1933) Coe went on to challenge the churches’ stance on religious education, its “walled-in” religious education. He also pointed out: The biggest problem of the separation of church from society was bringing the youth to Christ. While the churches were pursuing the priestly function in the churches, the schools and the society were giving the students and the young people ultimate value to promote a secularistic life aparted from Christian understanding and vocation. -

Varian Fry Institute 1

Varian Fry Institute 1 Varian's War By Those Who Know 7 Varian Fry in Marseille by Pierre Sauvage 13 MIRIAM DAVENPORT EBEL (1915 - 1999) 54 An Unsentimental Education 59 Mary Jayne Gold a synopsis by the author 87 The Varian Fry Institute is sponsored by the Chambon Foundation Pierre Sauvage, President Revised: February 12, 2008 Varian Fry Institute dedicated to Americans Who Cared When the world turned away, one American led the most determined and successful American rescue operation of the Nazi era. Mary Jayne Gold (1909-1997) prior to World War II Fry and Colleagues Page 1 of 89 Varian Fry (1907-1967) in Marseille in 1941 No stamp for the 100th anniversary of his birth Miriam Davenport Ebel (1915-1999) prior to World War II Charles Fawcett (1915-2008) in Ambulance Corps uniform Fry and Colleagues Page 2 of 89 Hiram Bingham IV (1903-1988) righteous vice-consul in 1940-41, stamp issued in May 2006 Leon Ball “In all we saved some two thousand human beings. We ought to have saved many times that number. But we did what we could.” Varian Fry Viewed within the context of its times, Fry's mission in Marseille, France, in 1940-41 seems not "merely" an attempt to save some threatened writers, artists, and political figures. It appears in hindsight like a doomed final quest to reverse the very direction in which the world—and not merely the Nazis— was heading. from Varian Fry in Marseille, by Pierre Sauvage We are very sad to announce the death of our friend Charles Fernley Fawcett. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E1731 HON

September 14, 2006 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1731 wife, Martha Sharp, who were true heroes of courageously returning to Europe to aid more to the family and the community and our sym- the Holocaust who risked their lives to save people flee the horror of the Nazi regime. pathy goes out to them. We are grateful for Jews from the atrocities of the Nazi regime. By the time the Sharps arrived in Europe, his service to our county.’’ The Sharps’ incredible story was told this the Nazis had already occupied France, but Travis was a life-long resident of Boyertown, morning at a very moving ceremony at the the Sharps were undaunted. They set up the Pennsylvania and is the son of Gail United States Holocaust Memorial Museum American Unitarian Universalist Service Com- Camperson and Lloyd Zimmerman. After where family, friends, and admirers gathered mittee in Lisbon, Portugal, from where they Travis’s graduation in June of 2005, he at- to pay tribute and remember the selfless and continued to assist many more refugees from tended basic training and then joined the laudatory actions of this amazing couple. Their war-torn Europe escape to safety. Army’s 101st Airborne unit. Travis’s unit de- story was also a powerful reminder that all of In all, the Sharps and their Unitarian col- ployed to Iraq in February 2006. us have the moral obligation to do anything leagues worked to save approximately 2,000 Scarlett Kulp, Travis’s life long friend, want- we can to end violence and genocides where men, women, and children.