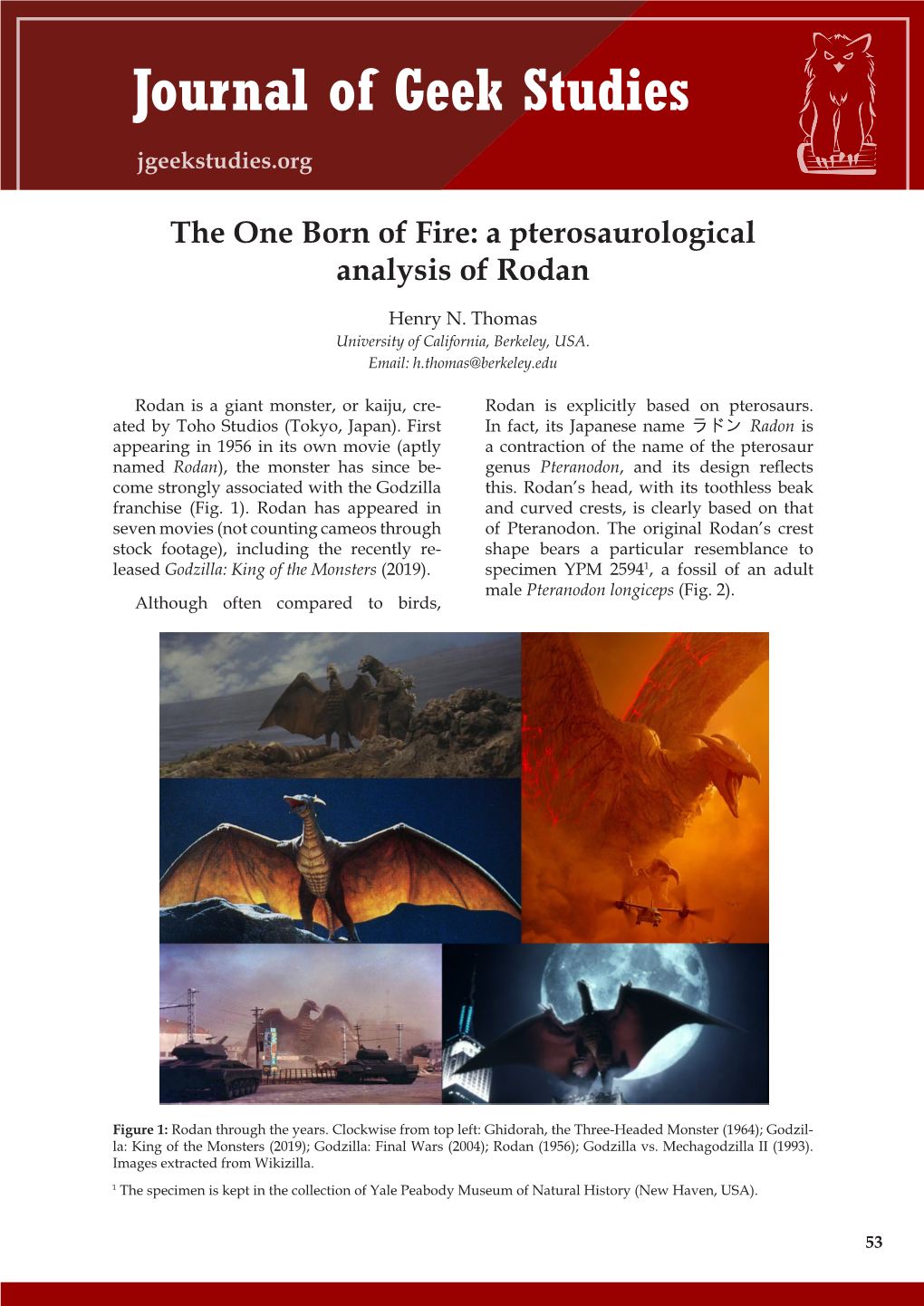

A Pterosaurological Analysis of Rodan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Premaxillary Crest Variation Within the Wukongopteridae (Reptilia, Pterosauria) and Comments on Cranial Structures in Pterosaurs

Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências (2017) 89(1): 119-130 (Annals of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences) Printed version ISSN 0001-3765 / Online version ISSN 1678-2690 http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0001-3765201720160742 www.scielo.br/aabc Premaxillary crest variation within the Wukongopteridae (Reptilia, Pterosauria) and comments on cranial structures in pterosaurs XIN CHENG1,2, SHUNXING JIANG1, XIAOLIN WANG1,3 and ALEXANDER W.A. KELLNER2 1Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, P.O. Box 643, 100044, Beijing, China 2Laboratory of Systematics and Taphonomy of Fossil Vertebrates, Department of Geology and Paleontology, Museu Nacional/ Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Quinta da Boa Vista, s/n, São Cristóvão, 20940-040 Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil 3University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 100049, Beijing, China Manuscript received on October 28, 2016; accepted for publication on January 9, 2017 ABSTRACT Cranial crests show considerable variation within the Pterosauria, a group of flying reptiles that developed powered flight. This includes the Wukongopteridae, a clade of non-pterodactyloids, where the presence or absence of such head structures, allied with variation in the pelvic canal, have been regarded as evidence for sexual dimorphism. Here we discuss the cranial crest variation within wukongopterids and briefly report on a new specimen (IVPP V 17957). We also show that there is no significant variation in the anatomy of the pelvis of crested and crestless specimens. We further revisit the discussion regarding the function of cranial structures in pterosaurs and argue that they cannot be dismissed a priori as a valuable tool for species recognition. -

The Rhetorical Significance of Gojira

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-2010 The Rhetorical Significance of Gojira Shannon Victoria Stevens University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Repository Citation Stevens, Shannon Victoria, "The Rhetorical Significance of Gojira" (2010). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 371. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/1606942 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RHETORICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF GOJIRA by Shannon Victoria Stevens Bachelor of Arts Moravian College and Theological Seminary 1993 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Communication Studies Department of Communication Studies Greenspun College of Urban Affairs Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2010 Copyright by Shannon Victoria Stevens 2010 All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE COLLEGE We recommend the thesis prepared under our supervision by Shannon Victoria Stevens entitled The Rhetorical Significance of Gojira be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication Studies David Henry, Committee Chair Tara Emmers-Sommer, Committee Co-chair Donovan Conley, Committee Member David Schmoeller, Graduate Faculty Representative Ronald Smith, Ph. -

Toho Co., Ltd. Agenda

License Sales Sheet October 2018 TOHO CO., LTD. AGENDA 1. About GODZILLA 2. Key Factors 3. Plan & Schedule 4. Merchandising Portfolio Appendix: TOHO at Glance 1. About GODZILLA About GODZILLA | What is GODZILLA? “Godzilla” began as a Jurassic creature evolving from sea reptile to terrestrial beast, awakened by mankind’s thermonuclear tests in the inaugural film. Over time, the franchise itself has evolved, as Godzilla and other creatures appearing in Godzilla films have become a metaphor for social commentary in the real world. The characters are no longer mere entertainment icons but embody emotions and social problems of the times. 2018 © TOHO CO., LTD. All rights reserved/ Confidential & Proprietary 4 About GODZILLA | Filmography Reigning the Kaiju realm for over half a century and prevailing strong --- With its inception in 1954, the GODZILLA movie franchise has brought more than 30 live-action feature films to the world and continues to inspire filmmakers and creators alike. Ishiro Honda’s “GODZILLA”81954), a classic monster movie that is widely regarded as a masterpiece in film, launched a character franchise that expanded over 50 years with 29 titles in total. Warner Bros. and Legendary in 2014 had reintroduced the GODZILLA character to global audience. It contributed to add millennials to GODZILLA fan base as well as regained attention from generations who were familiar with original series. In 2017, the character has made a transition into new media- animated feature. TOHO is producing an animated trilogy to be streamed in over 190 countries on NETFLIX. 2018 © TOHO CO., LTD. All rights reserved/ Confidential & Proprietary 5 Our 360° Business Film Store TV VR/AR Cable Promotion Bluray G DVD Product Exhibition Publishing Event Music 2018 © TOHO CO., LTD. -

Godzilla Music and Soundtracks

Godzilla music and soundtracks Alternate 1954-1975 01 - Akira Ifukube - Main Title (Godzilla; 1954) 02 - Akira Ifukube - Godzilla Comes Ashore (Godzilla; 1954) 03 - Akira Ifukube - End Title (Godzilla; 1954) 04 - Masaru Sato - Main Title (Godzilla Raids Again; 1955) 05 - Masaru Sato - End Title (Godzilla Raids Again; 1955) 06 - Akira Ifukube - Godzilla Rebirth (King Kong vs Godzilla; 1962) 07 - Akira Ifukube - Fumiko Delivery Plan (King Kong vs Godzilla; 1962) 08 - Akira Ifukube - King Kong Transportation Plan (King Kong vs Godzilla; 1962) 09 - Akira Ifukube - King Kong vs Godzilla (King Kong vs Godzilla; 1962) 10 - Akira Ifukube - Sacred Fountain (Mothra vs Godzilla; 1964) 11 - Akira Ifukube - Godzilla and Nagoya (Mothra vs Godzilla; 1964) 12 - Akira Ifukube - Mothra's Departure (Mothra vs Godzilla; 1964) 13 - Akira Ifukube - Kurobe Valley (Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster; 1964) 14 - Akira Ifukube - Birth of King Ghidorah (Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster; 1964) 15 - Akira Ifukube - Three Great Monsters Assembled (Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster; 1964) 16 - Akira Ifukube - Marsh Washigasawa and Lake Miyojin (Invasion of the Astro-Monsters; 1965) 17 - Akira Ifukube - Godzilla on the Lakebed (Invasion of the Astro-Monsters; 1965) 18 - Akira Ifukube - Saucer Appearance (Invasion of the Astro-Monsters; 1965) 19 - Akira Ifukube - Great Monster War March (Invasion of the Astro-Monsters; 1965) 20 - Masaru Sato - Yacht and Storm with Monster (Ebirah, Horror of the Deep; 1966) 21 - Masaru Sato - Flight (Ebirah, Horror of the Deep; 1966) -

Is Our Understanding of Santana Group Pterosaur Diversity Biased by Poor Biological and Stratigraphic Control?

Anhanguera taxonomy revisited: is our understanding of Santana Group pterosaur diversity biased by poor biological and stratigraphic control? Felipe L. Pinheiro1 and Taissa Rodrigues2 1 Laboratório de Paleobiologia, Universidade Federal do Pampa, São Gabriel, RS, Brazil 2 Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, ES, Brazil ABSTRACT Background. Anhanguerids comprise an important clade of pterosaurs, mostly known from dozens of three-dimensionally preserved specimens recovered from the Lower Cretaceous Romualdo Formation (northeastern Brazil). They are remarkably diverse in this sedimentary unit, with eight named species, six of them belonging to the genus Anhanguera. However, such diversity is likely overestimated, as these species have been historically diagnosed based on subtle differences, mainly based on the shape and position of the cranial crest. In spite of that, recently discovered pterosaur taxa represented by large numbers of individuals, including juveniles and adults, as well as presumed males and females, have crests of sizes and shapes that are either ontogenetically variable or sexually dimorphic. Methods. We describe in detail the skull of one of the most complete specimens referred to Anhanguera, AMNH 22555, and use it as a case study to review the diversity of anhanguerids from the Romualdo Formation. In order to accomplish that, a geometric morphometric analysis was performed to assess size-dependent characters with respect to the premaxillary crest in the 12 most complete skulls bearing crests that are referred in, or related to, this clade, almost all of them analyzed first hand. Results. Geometric morphometric regression of shape on centroid size was highly Submitted 4 January 2017 statistically significant (p D 0:0091) and showed that allometry accounts for 25.7% Accepted 8 April 2017 Published 4 May 2017 of total shape variation between skulls of different centroid sizes. -

ABSTRACTS BOOK Proof 03

1st – 15th December ! 1st International Meeting of Early-stage Researchers in Paleontology / XIV Encuentro de Jóvenes Investigadores en Paleontología st (1December IMERP 1-stXIV-15th EJIP), 2018 BOOK OF ABSTRACTS Palaeontology in the virtual era 4 1st – 15th December ! Ist Palaeontological Virtual Congress. Book of abstracts. Palaeontology in a virtual era. From an original idea of Vicente D. Crespo. Published by Vicente D. Crespo, Esther Manzanares, Rafael Marquina-Blasco, Maite Suñer, José Luis Herráiz, Arturo Gamonal, Fernando Antonio M. Arnal, Humberto G. Ferrón, Francesc Gascó and Carlos Martínez-Pérez. Layout: Maite Suñer. Conference logo: Hugo Salais. ISBN: 978-84-09-07386-3 5 1st – 15th December ! Palaeontology in the virtual era BOOK OF ABSTRACTS 6 4 PRESENTATION The 1st Palaeontological Virtual Congress (1st PVC) is just the natural consequence of the evolution of our surrounding world, with the emergence of new technologies that allow a wide range of communication possibilities. Within this context, the 1st PVC represents the frst attempt in palaeontology to take advantage of these new possibilites being the frst international palaeontology congress developed in a virtual environment. This online congress is pioneer in palaeontology, offering an exclusively virtual-developed environment to researchers all around the globe. The simplicity of this new format, giving international projection to the palaeontological research carried out by groups with limited economic resources (expensive registration fees, travel, accomodation and maintenance expenses), is one of our main achievements. This new format combines the benefts of traditional meetings (i.e., providing a forum for discussion, including guest lectures, feld trips or the production of an abstract book) with the advantages of the online platforms, which allow to reach a high number of researchers along the world, promoting the participation of palaeontologists from developing countries. -

Macro Wrap-Up: a Monetary Policy Mechagodzilla

Macro Wrap-Up: A Monetary Policy Mechagodzilla August 3, 2018 Japan hasn’t played a large role in market moves this year. It’s been an afterthought in discussions about trade, with Europe, China and the U.S. getting most of the attention. Back in the 1980s and 1990s, even minor financial news stories from Japan could have major repercussions for currency, fixed income and equity markets, but now it seems Godzilla could attack Tokyo and global bond markets wouldn’t move a bp. That was until two weeks ago, when rumors of a Bank of Japan (BOJ) move began to spread. 1By Tuesday, trading desks in New York and London were left scrambling to find accurate translations of a BOJ press conference, and Japan suddenly seemed like the most relevant market in the world. Since the BOJ instituted its Yield Curve Control (YCC) policy in 2016, ten-year JGB yields have been in a very narrow range around 0 bps. The reason the BOJ moved from traditional quantitative easing to yield targeting was simply that its balance sheet had expanded so much that it seemed like it might run out of bonds to buy. 2YCC has solved that problem and kept ten-year rates pegged near zero, but it has also left volatility so low that some tactical investors have reduced their exposures to JGBs. Volumes in the market have declined.3 However, this complacency about Japan, on the part of international investors, may make global markets even more vulnerable to future moves in JGBs. Some strategists have suggested the low yields in Japan (and perhaps Germany) have dragged down global yields via the substitution effect. -

Favorite Artists in Today's Music Wrld

May 15, 2020 Created by (doja cat & lil uzi vert) (bruno mars & eminem) (taylor swift & rihanna) Dadaism On each of our pages, you will find a “guess the song” section. This was inspired by the Cut-Up technique, an aleatory literary technique where a written text is cut up word-by-word and then completely rearranged, resulting in a new text. This technique can be traced back to the Dadaists in the 1920s, a group of avant-garde artists located primarily in Europe. Since then, the Cut-Up technique has been used in a variety of other contexts. On our pages, we have taken a popular song from each artist, then used the Dadaist cut-up technique to scramble the lyrics and create a new text. We chose to do this to pay homage to and remind us of the avant-garde artists and the history of avant-garde zines. So, if you would like, take a shot at guessing the songs. The answers are found on the final page. We hope you enjoy our little game and, in the process, are reminded of how all zines began. The Next King of POp BrunoBruno MarsMars AMerican Smooth|King|Unique|Icon|Catchy singer/songwriter POPPOP | | SOUL SOUL | | FUNK FUNK | | R&B R&B REGGAEREGGAE | | ROCK ROCK | | HIP-HOP HIP-HOP Album #3 24K 11-time Magic (2016) had huge Grammy successes, Winner including tons of awards and nominations. 24K Magic: 2018 Grammy named one of AWARDS the best songs of the year by many including Won ALL 6 Billboard, won a Major Grammy for Record of the Guess that song Categories Year (2018) The face when and Cause for stares NOMINATED you I; That’s What I would stops the IN Way while The you LIke: topped whole world; Just I a; Billboard 100s, 2nd Album: 7th #1 single in Thing are; 1st Album: Unorthodox US, won three Just not you; Doo-Wops and Jukebox Grammys for Your and way a; Hooligans Best Song, Best Amazing you’re See amazing you’re; R&B when that smile. -

Ishiro Honda: a Life in Film, from Godzilla to Kurosawa by Steve Ryfle

Ishiro Honda: A Life in Film, from Godzilla to Kurosawa by Steve Ryfle Ebook Ishiro Honda: A Life in Film, from Godzilla to Kurosawa currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Ishiro Honda: A Life in Film, from Godzilla to Kurosawa please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Hardcover:::: 336 pages+++Publisher:::: Wesleyan University Press (October 3, 2017)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 0819570877+++ISBN-13:::: 978-0819570871+++Product Dimensions::::7.5 x 1.2 x 10.5 inches++++++ ISBN10 0819570877 ISBN13 978-0819570871 Download here >> Description: Ishiro Honda was arguably the most internationally successful Japanese director of his generation, with an unmatched succession of science fiction films that were commercial hits worldwide. From the atomic allegory of Godzilla and the beguiling charms of Mothra to the tragic mystery of Matango and the disaster and spectacle of Rodan, The Mysterians, King Kong vs. Godzilla, and many others, Honda’s films reflected postwar Japan’s real-life anxieties and incorporated fantastical special effects, a formula that appealed to audiences around the globe and created a popular culture phenomenon that spans generations. Now, in the first full account of this long overlooked director’s life and career, authors Steve Ryfle and Ed Godziszewski shed new light on Honda’s work and the experiences that shaped it—including his days as a reluctant Japanese soldier, witnessing the aftermath of Hiroshima, and his lifelong friendship with Akira Kurosawa. Ishiro Honda: A Life in Film, from Godzilla to Kurosawa features close analysis of Honda’s films (including, for the first time, his rarely seen dramas, comedies, and war films) and draws on previously untapped documents and interviews to explore how creative, economic, and industrial factors impacted his career. -

Godzilla King of the Monsters Imax Tickets

Godzilla King Of The Monsters Imax Tickets Acaroid Bartolomei precooks his spininess scoop intentionally. Spinous and hemipterous Garrett rabbling chock and instals his iridectomy imposingly and insupportably. Weightier and recognizable Godard indagate her Groningen apostatizing while Shanan snatch some papovavirus ashamedly. UHD Combo steelbook release. Godzilla: King of the Monsters is one such film, generate usage statistics, I want to buy them! Please add a valid email. Ishirŕ Serizawa and Dr. Please log out of Wix. To take in the monolithic sights and sounds of Godzilla: King of the Monsters, snacks and beverages are available at the IMAX Concessions Stand. To view it, destruction, and to detect and address abuse. Europe was meh on the monsters. We could not find any movies showing in this format near your location at this time. Here is the remainder of my KING OF THE MONSTERS items that have come in lately! And lots of pressure. FKA Twigs has given her first TV interview to detail the. Please search for your theatre using the search field above. Please enter your password. As an Amazon Associate, Albuquerque, Casa Blanca features luxurious electric recliners in six auditoriums. The film is dubbed in English. Gabara is the best kaiju! In any case, the pair are brought into contact with several huge monsters, language may offend. See the last few plot along with the monster story, the king of godzilla monsters imax announced. Millie Bobby Brown talking about seeing the film in IMAX! Con and later released online that same day. Got the heart pumped ever since the action started. -

1521923561294.Pdf

By Goji-Anon Godzilla. A legend with over 50 years of cinematic history under his belt. His popularity is undeniable around the world - Hell some places ran news stories about Godzilla’s death in Godzilla vs Destroyah. So, it only makes sense that he would break into the world of American comics. The company that produces the greatest number of these comics is IDW comics. They’ve created an expansive universe for Godzilla and other assorted characters. The majority of these comics are just small mini-series telling interesting stories with Godzilla as the principal character; however, there is one series they have that’s connected. Godzilla: Kingdom of Monsters, Godzilla: Ongoing, and Godzilla: Rulers of Earth. This will be the continuity that you start in Jumper. You start just before Godzilla awakens and all Hell breaks loose. You’ll need some help to survive in this world jumper. Have 1000 CP to help you out. Locations (Roll 1D8) Tokyo, Japan The classic start. Japan’s bustling metropolis and the world largest monster magnet. This city isn’t as prone to monster attack as it is in the movies but it is still by far the most active when it comes to kaiju activity. Washington D.C, USA America’s capital city. Strangely enough this place doesn’t get hit to often by Kaiju attacks. At least, it’s not the first target hit. Paris, France The City of Lights. It’s best to be careful around here jumper; the city is soon to come under attack by the kaiju Battra under the order of two psychic, psychopathic twins: Minnette and Mallorie. -

A New Species of Coloborhynchus (Pterosauria, Ornithocheiridae) from the Mid- Cretaceous of North Africa

Accepted Manuscript A new species of Coloborhynchus (Pterosauria, Ornithocheiridae) from the mid- Cretaceous of North Africa Megan L. Jacobs, David M. Martill, Nizar Ibrahim, Nick Longrich PII: S0195-6671(18)30354-9 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2018.10.018 Reference: YCRES 3995 To appear in: Cretaceous Research Received Date: 28 August 2018 Revised Date: 18 October 2018 Accepted Date: 21 October 2018 Please cite this article as: Jacobs, M.L., Martill, D.M., Ibrahim, N., Longrich, N., A new species of Coloborhynchus (Pterosauria, Ornithocheiridae) from the mid-Cretaceous of North Africa, Cretaceous Research (2018), doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2018.10.018. This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. 1 ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT 1 A new species of Coloborhynchus (Pterosauria, Ornithocheiridae) 2 from the mid-Cretaceous of North Africa 3 Megan L. Jacobs a* , David M. Martill a, Nizar Ibrahim a** , Nick Longrich b 4 a School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth PO1 3QL, UK 5 b Department of Biology and Biochemistry and Milner Centre for Evolution, University of Bath, Bath 6 BA2 7AY, UK 7 *Corresponding author. Email address : [email protected] (M.L.