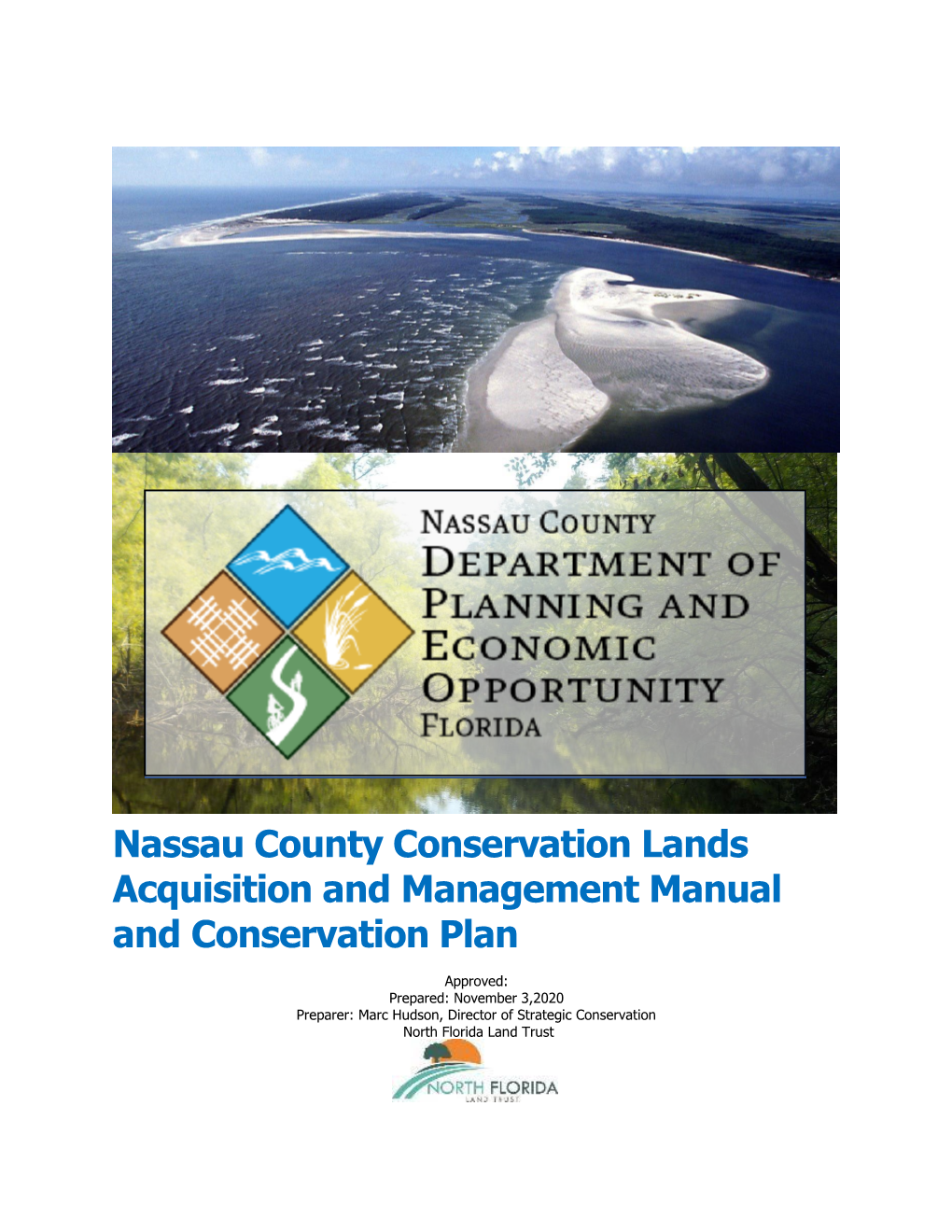

CLAM Manual and Conservation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

FLORIDA Coastal and Estuarine Land Conservation Plan SEPTEMBER 2008 (Originally submitted October 2006) Prepared by: Florida Coastal Management Program In cooperation with: Florida Department of Environmental Protection Division of State Lands Office of Coastal and Aquatic Managed Areas Florida Natural Areas Inventory ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many state partners and individuals assisted the Florida Coastal Management Program in developing the Florida Coastal and Estuarine Land Conservation Plan. The Florida Coastal Management Program would like to extend special thanks to the following for their assistance and support in developing this plan: From the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Division of State Lands O. Greg Brock, Donna Jones Ruffner and Ellen Stere From the Florida Natural Areas Inventory Gary Knight and Ann F. Johnson The Florida Coastal Management Program 3900 Commonwealth Blvd. MS #47 Tallahassee, FL 32399 Coastal Program URL: http://www.dep.state.fl.us/mainpage/programs/cmp.htm Development of this plan was supported with funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management under Section 306 of the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972. Florida Coastal and Estuarine Land Conservation Plan Overview of conservation lands in the State of Florida ii Florida Coastal and Estuarine Land Conservation Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 1 a. Background -

12 TOP BEACHES Amelia Island, Jacksonville & St

SUMMER 2014 THE COMPLETE GUIDE TO GO® First Coast ® wheretraveler.com 12 TOP BEACHES Amelia Island, Jacksonville & St. Augustine Plus: HANDS-ON, HISTORIC ATTRACTIONS SHOPPING, GOLF & DINING GUIDES JAXWM_1406SU_Cover.indd 1 5/30/14 2:17:15 PM JAXWM_1406SU_FullPages.indd 2 5/19/14 3:01:04 PM JAXWM_1406SU_FullPages.indd 1 5/19/14 2:59:15 PM First Coast Summer 2014 CONTENTS SEE MORE OF THE FIRST COAST AT WHERETRAVELER.COM The Plan The Guide Let’s get started The best of the First Coast SHOPPING 4 Editor’s Itinerary 28 From the scenic St. Johns River to the beautiful Atlantic Your guide to great, beaches, we share our tips local shopping, from for getting out on the water. Jacksonville’s St. Johns Avenue and San Marco Square to King Street in St. Augustine and Centre Street in Amelia Island. 6 Hot Dates Summer is a season of cel- ebrations, from fireworks to farmers markets and 32 MUSEUMS & concerts on the beach. ATTRACTIONS Tour Old Town St. 48 My First Coast Augustine in grand Cindy Stavely 10 style in your very own Meet the person behind horse-drawn carriage. St. Augustine’s Pirate Museum, Colonial Quarter 14 DINING & and First Colony. Where Now NIGHTLIFE 46..&3 5)&$0.1-&5&(6*%&50(0 First Coast ® Fresh shrimp just tastes like summer. Find out wheretraveler.com 9 Amelia Island 12 TO P BEACHES where to dig in and Amelia Island, Jacksonville & St. Augustine From the natural and the historic to the posh and get your hands dirty. luxurious, Amelia Island’s beaches off er something for every traveler. -

Florida State Parks Data by 2021 House District

30, Florida State Parks FY 2019-20 Data by 2021 House Districts This compilation was produced by the Florida State Parks Foundation . FloridaStateParksFoundation.org Statewide Totals • 175 Florida State Parks and Trails (164 Parks / 11 Trails) comprising nearly 800,000 Acres • $2.2 billion direct impact to Florida’s economy • $150 million in sales tax revenue • 31,810 jobs supported • 25 million visitors served # of Economic Jobs Park House Districts Parks Impact Supported Visitors 1 Salzman, Michelle 0 2 Andrade, Robert Alexander “Alex” 3 31,073,188 436 349,462 Big Lagoon State Park 10,336,536 145 110,254 Perdido Key State Park 17,191,206 241 198,276 Tarklin Bayou Preserve State Park 3,545,446 50 40,932 3 Williamson, Jayer 3 26,651,285 416 362,492 Blackwater Heritage State Trail 18,971,114 266 218,287 Blackwater River State Park 7,101,563 99 78,680 Yellow River Marsh Preserve State Park 578,608 51 65,525 4 Maney, Thomas Patterson “Patt” 2 41,626,278 583 469,477 Fred Gannon Rocky Bayou State Park 7,558,966 106 83,636 Henderson Beach State Park 34,067,312 477 385,841 5 Drake, Brad 9 64,140,859 897 696,022 Camp Helen State Park 3,133,710 44 32,773 Deer Lake State Park 1,738,073 24 19,557 Eden Gardens State Park 3,235,182 45 36,128 Falling Waters State Park 5,510,029 77 58,866 Florida Caverns State Park 4,090,576 57 39,405 Grayton Beach State Park 17,072,108 239 186,686 Ponce de Leon Springs State Park 6,911,495 97 78,277 Three Rivers State Park 2,916,005 41 30,637 Topsail Hill Preserve State Park 19,533,681 273 213,693 6 Trumbull, Jay 2 45,103,015 632 504,860 Camp Helen State Park 3,133,710 44 32,773 St. -

Class G Tables of Geographic Cutter Numbers: Maps -- by Region Or

G3862 SOUTHERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3862 FEATURES, ETC. .C55 Clayton Aquifer .C6 Coasts .E8 Eutaw Aquifer .G8 Gulf Intracoastal Waterway .L6 Louisville and Nashville Railroad 525 G3867 SOUTHEASTERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3867 FEATURES, ETC. .C5 Chattahoochee River .C8 Cumberland Gap National Historical Park .C85 Cumberland Mountains .F55 Floridan Aquifer .G8 Gulf Islands National Seashore .H5 Hiwassee River .J4 Jefferson National Forest .L5 Little Tennessee River .O8 Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail 526 G3872 SOUTHEAST ATLANTIC STATES. REGIONS, G3872 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .B6 Blue Ridge Mountains .C5 Chattooga River .C52 Chattooga River [wild & scenic river] .C6 Coasts .E4 Ellicott Rock Wilderness Area .N4 New River .S3 Sandhills 527 G3882 VIRGINIA. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G3882 .A3 Accotink, Lake .A43 Alexanders Island .A44 Alexandria Canal .A46 Amelia Wildlife Management Area .A5 Anna, Lake .A62 Appomattox River .A64 Arlington Boulevard .A66 Arlington Estate .A68 Arlington House, the Robert E. Lee Memorial .A7 Arlington National Cemetery .A8 Ash-Lawn Highland .A85 Assawoman Island .A89 Asylum Creek .B3 Back Bay [VA & NC] .B33 Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge .B35 Baker Island .B37 Barbours Creek Wilderness .B38 Barboursville Basin [geologic basin] .B39 Barcroft, Lake .B395 Battery Cove .B4 Beach Creek .B43 Bear Creek Lake State Park .B44 Beech Forest .B454 Belle Isle [Lancaster County] .B455 Belle Isle [Richmond] .B458 Berkeley Island .B46 Berkeley Plantation .B53 Big Bethel Reservoir .B542 Big Island [Amherst County] .B543 Big Island [Bedford County] .B544 Big Island [Fluvanna County] .B545 Big Island [Gloucester County] .B547 Big Island [New Kent County] .B548 Big Island [Virginia Beach] .B55 Blackwater River .B56 Bluestone River [VA & WV] .B57 Bolling Island .B6 Booker T. -

Reference Guide 2020

P a g e | 1 Reference Guide 2020 This Reference Guide is provided by the Amelia Island Convention & Visitors Bureau for tourism industry partners for information purposes only. It is not to be given out to the general public. Information is subject to change without notice. Please notify our office at 904-277-0717 of any discrepancies, updates or corrections. Amelia Island Welcome Center 102 Centre Street, Amelia Island, Florida 32034 www.AmeliaIsland.com For Internal Use Only 8/5/2020 P a g e | 2 Table of Contents AICVB 3 Local Numbers 4 Frequently Asked Questions 5 Hurricanes 6 Red Tides 7 Rip Currents 9 Shark Encounters 10 STAY – Accommodations 11 SHOP – Retail 12 EAT – Dining & Libations 15 SEE & DO – Recreation & Activities 18 SEE & DO – Wellness & Spa 21 Transportation and Ferry Services 22 Beach Information 23 Warning Flags 24 Public Beach Accesses 24 Fishing 25 Marinas & Boat Ramps 26 City, County and State Parks 27 Churches 29 Annual Events 30 Miscellaneous Information 31 Climate 32 For Internal Use Only 8/5/2020 P a g e | 3 AMELIA ISLAND CONVENTION & VISITOR BUREAU (AICVB) Administration Office: 2398 Sadler Road, Suite 200 | 904-277-4369 |Fax: 904-432-8417 Welcome Center (Historic Train Depot): 102 Centre Street | 904-277-0717 Amelia Island, Florida 32034 Toll Free: 1-800-2AMELIA (1-800-226-3542) www.AmeliaIsland.com Amelia Island Convention & Visitors Bureau Staff Name Title Phone # Cell Phone EMAIL Gil Langley President/CEO 904-432-2227 904-483-0214 [email protected] Chief Marketing Amy Boek 904-432-2226 904-753-6531 -

Avvlelllli 1Sll!I0v0t Plltr~Wlltlj Mvtltl-Vtse Trllill

}lpplication Por: Transportation Alternatives Projects Funding FY 2021 AVvleLLllI !sLl!I0v0t TrllILL Pvtlltse !! (AVvleLLllI 1sLl!I0v0t Plltr~Wlltlj MvtLtL-vtse TrllILL) Joint{y Su6mitted(By: Nassau County Board of Commissioners & City Commission of Fernandina Beach Su6mitted <To: North Florida Transportation Planning Orginization August 1, 2014 :Nassau County qrowth :Management <Department Contents: 1. Application Form For Transportation Alternatives Projects 2. Exhibits(Tabs): Exhibit A - Application Text Response to Questions 2.A - 2.E Exhibit B - Application Text Response to Questions 3 .A - 3 .E Exhibit C - Map Series AIT-II Exhibit D - Map 8 of Map Series RMP2030 Exhibit E - NFTPO(aka. FCMPO) Regional Greenways and Trail Plan(2006) excerpts; pages 16, 17, 28-30 Exhibit F - Florida Greenways and Trails System Plan(FGTS) Land Trail Opportunity and Priority Network excerpts Exhibit G - Florida Greenways & Trails Foundation, Inc., 'Close the Gap' excerpts Exhibit H - East Coast Greenway Florida Route Map Exhibit I - ROW Maps/Plats Compact Disk Exhibit J - Letters of Support Exhibit K - City of Fernandina Beach Resolution 2014-58 Exhibit L - Nassau County Board of Commissioners Meeting Minutes and Agenda Packet Exhibit M - Cost Estimates .... ::-.· __ . ... - ..=---=--:--- -_:- FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION District 2 APPLICATION FOR TRANSPORTATION November 2012 ALTERNATIVES PROJECTS Page rot 4 Oate: AUGUST 1, 2014 Project Title: AMELIA ISLAND TRAIL PHASE II {AMELIA ISLAND PARKWAY MULTI-USE TRAIL) Project Sponsor (name of city, county, state, federal agency, or MPO): NASSAU COUNTY BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS AND THE CITY COMMISSION OF FERNANDINA BEACH (JOINT APPLICANTS) Contact TACO E. POPE. AICP Title SENIOR PLANNER Agency NASSAU COUNTY BOCC Address 96161 NAssAu PLACE, vuLEE, FL 32097 Phone (904) 491-7328 Email [email protected] Priority (relative to other applications submitted by the Project Sponsor) _F1_R_ST_PR_1_o_R1_TY_____ _ Name of Applicant (If other than contact person) _sA_M_E _________________ 1. -

The State of Florida Issues COVID-19 Updates

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 21, 2020 Contact: Joint Information Center on COVID-19 for the State of Florida (850) 815-4940, [email protected] The State of Florida Issues COVID-19 Updates TALLAHASSEE, Fla. - The State of Florida is responding to COVID-19. In an effort to keep Florida residents and visitors safe and aware regarding the status of the virus, the Florida Department of Health will issue this update every day, seven days per week. Governor Ron DeSantis is in constant communication with Florida Division of Emergency Management Director Jared Moskowitz and State Surgeon General Dr. Scott Rivkees as the State of Florida continues to monitor and respond to the threat of COVID-19. Today, in a briefing at the State Emergency Operations Center, Governor DeSantis announced more actions on COVID-19: • Broward’s Memorial Healthcare System drive-through test site collected 745 samples in the first day of operation. The site received 5,000 additional collection kits for use. • Three new federally supported test sites will be opening in the next week in Jacksonville, Orlando and Miami. These sites will test those 65 or older with symptoms of COVID-19, and first responders and healthcare workers regardless of symptoms. o The Jacksonville site at TIAA Bank Field Lot J opened today. o The Miami-Dade County site at Hard Rock Stadium is set to open on Monday. o The Orlando site at the Orange County Convention Center is set to open on Wednesday. • Today, the Florida Division of Emergency Management sent collection kits out to the following -

3Rd Year Anniversary Presentation

Welcome! 3 Year Anniversary 2009-2012 Reception and Celebration Sponsored by Longleaf Partnership Council March 13, 2012 Atlanta, GA TX-LA Longleaf Taskforce (Photo by Ross Anderson) TX-LA Longleaf Taskforce (Photo by Ross Anderson) TX-LA Longleaf Taskforce (Photo by Ross Anderson) TX-LA Longleaf Taskforce (Photo by Ross Anderson) TX-LA Longleaf Taskforce (Photo by Ross Anderson) TX-LA Longleaf Taskforce (Photo by Ross Anderson) TX-LA Longleaf Taskforce (Photo by Ross Anderson) TX-LA Longleaf Taskforce (Photo by Ross Anderson) TX-LA Longleaf Taskforce (Photo by Ross Anderson) TX-LA Longleaf Taskforce (Photo by Ross Anderson) TX-LA Longleaf Taskforce (Photo by Ross Anderson) TX-LA Longleaf Taskforce (Photo by Ross Anderson) Mark Hainds discusses understory diversity at Longleaf 101 Academy in Tifton, Georgia. (Longleaf Alliance) Prescribed Fire in Blackwater River State Forest (Photo by Vernon Compton) Eglin Air Force Base, FL (Photo by Vernon Compton) Eglin Air Force Base, FL (Photo by Vernon Compton) Eglin Air Force Base, FL (Photo by Vernon Compton) Eglin Air Force Base, FL (Photo by Vernon Compton) Eglin Air Force Base, FL (Photo by Vernon Compton) Eglin Air Force Base, FL (Photo by Vernon Compton) Eglin Air Force Base, FL (Photo by Vernon Compton) Eglin Air Force Base, FL (Photo by Vernon Compton) Eglin Air Force Base, FL (Photo by Vernon Compton) Ft. Benning ,GA (Photo by Vernon Compton) Ft. Benning ,GA (Photo by Vernon Compton) Ichauway Plantation, GA Ichauway Plantation, GA Ichauway Plantation, GA Ichauway Plantation, GA Ichauway -

Quarterly Report 1 September to 31 December 2011

Quarterly Report 1 September to 31 December 2011 Central Regional Center Florida Public Archaeology Network University of South Florida Department of Anthropology in cooperation with the Crystal River Preserve State Park 3266 Sailboat Avenue Crystal River, Florida 34428 31 January 2012 Central Regional Center Quarterly Report September - December 2011 Page 1 of 9 Executive Summary The September to December quarter at the Central Regional Center (CRC) included participation in many of our favorite events – Ocali Country Days, the heritage kayak tours, and the Crystal River Preserve State Park’s annual Halloween celebration. The cooler weather is also perfect for outdoor outreach. The Crystal River Archaeological State Park’s Moon Over the Mounds and Sifting for Technology programs have a full schedule this fall. The Historic Cemetery Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) program continues to be very popular with local historic groups and societies and extremely successful for community outreach. We returned to Rookery Bay Preserve near Naples, Florida to partner with the Southwest Regional Center to complete the GPR study of the Kirkland Cemetery and investigate the possible location of the Bolger Family Cemetery. The second fiscal quarter also saw the hire of two new park rangers at the Crystal River Preserve State Park. Catherine Wunderlich and Ronnie Hartley joined the staff that will oversee the outreach programs at the Crystal River Archaeological Site Park. Both are experienced rangers and interpreters. Catherine came from the Lake Jackson Mounds Archaeological State Park and Ronnie came over from the Hillsborough River State Park. Jason and Rich have both been working to help the new ranger’s while they get up to speed on the public archaeology outreach and education component of the site. -

An Overview of Amelia Island, Florida

An Overview of Amelia Island, Florida Amelia Island Florida Go2AmeliaIsland VisitAmeliaIsland NATURAL FLORIDA EXPERIENCE Located in the northeastern tip of Florida, Amelia Island offers an unspoiled setting for relaxing and rewarding getaways. Amelia is 13 miles long and two miles wide, with preserved park lands at its northern and southern tips, making up nearly 10 percent of the entire island. Surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, Intracoastal Waterway, strong-currented Nassau Sound and one of the East’s largest and deepest inlets – Cumberland Sound – Amelia Island is edged with natural Appalachian quartz beaches and framed by sand dunes as tall as 40 feet. Treasured for her long stretches of quiet beach, natural beauty, unique history and charming seaport character, Amelia Island is consistently ranked among the best of the best, including: No. 2 Top 10 U.S. Island (Conde Nast Traveler’s Reader’s Choice Awards, 2018), the No. 6 Top U.S. Island (Travel + Leisure, 2018), Top Ten Most Romantic Destinations in Florida (Coastal Living, 2018) and No. 4 Happiest Seaside Town (Coastal Living, 2017). The island is home to an irresistible mix of spa, golf, dining, shopping and leisure activities, but for those who want pure rest, relaxation and quality time with loved ones, there is no better place than Amelia Island. DIVERSE ACCOMODATIONS From upscale resorts and charming bed and breakfast inns, to comfortable hotels at value rates, Amelia Island offers accommodations for everyone. With more than 20 places to stay and more than 2,500 rooms, visitors can choose properties located directly on the Atlantic Ocean, within walking distance of the historic district and much more. -

Special Conditions for Access to Public and Private Lands

Florida’s Wildlife Contingency Plan for Oil Spills – June 2012 Special Conditions for Access to Public and Private Lands Special Conditions for Access to Public and Private Lands This section will contain requirements for specific parks, refuges, management areas, etc. and will be developed by the managers of these facilities. If Special Use Permits are required, the permit should either be attached, or instructions for obtaining permits should be included. Private Property: Do not trespass on private property. If appropriate, ask permission to access the property from the land owner. If permission cannot be obtained to access the property, make a note, record waypoints, and move on to the next portion of the survey. Public Property: The purpose of this section is to identify any special operational considerations for RP contractors/agents searching for and/or recovering oiled wildlife on specific public lands/facilities. Name of Facility: County(ies): Contact(s): [Name/Number/Email] Required Lead Time: Types of Restrictions (see examples below) • Hours of Entry • Required accompaniment • Restricted or sensitive areas • Sensitive species or resources • Historic/cultural issues • Limited or difficult access • Over-flight restrictions • Homeland Security Issues • Permit required? 1 Florida’s Wildlife Contingency Plan for Oil Spills – June 2012 Special Conditions for Access to Public and Private Lands USFWS Contact in Florida USFWS Contacts in Florida Station Name Location Telephone PANAMA CITY ECOLOGICAL SERVICES FIELD OFFICE PANAMA CITY, FL 850-769-0552 SOUTH FLORIDA ECOLOGICAL SERVICES FIELD OFFICE VERO BEACH, FL 772-562-3909 NORTH FLORIDA ECOLOGICAL SERVICES FIELD OFFICE JACKSONVILLE, FL 904-731-3336 FLORIDA MIGRATORY BIRD PROGRAM HAVANA, FL 850-539-1684 WELAKA NATIONAL FISH HATCHERY WELAKA, FL 386-467-2374 CHASSAHOWITZKA NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE CRYSTAL RIVER, FL 352-563-2088 CEDAR KEYS NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE CHIEFLAND, FL 352-493-0238 LOWER SUWANNEE NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE CHIEFLAND, FL 352-493-0238 J.N. -

Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve One-Day Excursions Jacksonville is one of the largest metropolitan areas in the United States. Plan an excursion to explore the city’s urban and natural treasures. Listed below are many parks, museums, and attractions that are within the Timucuan Preserve or near the city of Jacksonville. Please call each site for up-to-date information regarding hours, prices and facilities. Park Areas Fort Caroline National Memorial Talbot Islands State Parks Home of the Timucuan Preserve Visitor Center, These two beautiful park areas offer nature this park memorializes the site of a 16th-century trails, campsites, picnic areas and lots of beach. French colony – the first European settlement in Open daily 8 am to sunset. Admission fee the area. Open daily 9 am to 5 pm, closed charged. Located off Hwy A1A, approx. 3 miles Thanksgiving, New Years Day, Christmas Day. north of the St. Johns River ferry. (904) 251 Free admission. 12713 Ft. Caroline Rd. (904) 2320, 641-7155, www.nps.gov/timu www.floridastateparks.org/littletalbotisland Fort Clinch State Park Theodore Roosevelt Area This restored Civil War fort from the 1840s is This 600-acre natural area within the surrounded by beaches and nature trails. Park Timucuan Preserve has over 5 miles of hiking offers fishing, campsites and picnic grounds. trails winding through one of North Florida’s Open daily 8 am to sundown; Fort open daily 9 most pristine areas. Summer hours: 6 am to 8 am to 5 pm. Located off Hwy A1A in Fernandina pm; Winter hours: 6 am to 6 pm.