Analysis of Hurdle Running at Various Inter-Hurdle Distances in an Elementary School PE Class Mitsuo Otsuka, Michiko Ito and Akira Ito

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Track and Field Skills — Striding, Hurdling, Hop, Step, and Jump

GRADES 5-8 LESSON FOCUS Track and Field Skills — Striding, Hurdling, Hop, Step, and Jump SHAPE Standards: DPE Outcomes: Equipment: 4 • I can listen to and use feedback provided by • High jump equipment my peer. • Batons • I can provide appropriate performance feedback • Stopwatches to my peers. • Tape measures • I can compliment classmates on their • Hurdles Instructions performance during physical education. Skills Introduce the following skills before proceeding to small group instruction. Striding In distance running, as compared with sprinting, the body is more erect and the motion of the arms is less pronounced. Pace is an important consideration. Runners should try to concentrate on the qualities of lightness, ease, relaxation, and looseness. Good striding action, a slight body lean, and good head position are also important. Runners should be encouraged to strike the ground with the heel first and then push off with the toes. Hurdling Several key points govern good hurdling technique. The runner should adjust his stepping pattern so that the takeoff foot is planted 3 to 5 feet from the hurdle. The lead foot is extended straight forward over the hurdle; the rear (trailing) leg is bent, with the knee to the side. The lead foot reaches for the ground, quickly followed by the trailing leg. The hurdler should avoid floating over the hurdle. Body lean is necessary. A hurdler may lead with the same foot over consecutive hurdles or may alternate the leading foot. Some hurdlers like to thrust both arms forward instead of a single arm. A consistent step pattern should be developed. Wands supported on blocks or cones can also be used as hurdles. -

Best Workouts· .Cross Country Journal

Best Workouts· .from the .Cross Country Journal Best Workouts from the Cross Country Journal Compiled from the first t-welve volumes of the Journal © 1995, IDEA, Inc. Publisher of the Cross Country Journal Contents by Subject Cross Training "Swimming Pool Training Program," Finanger, Kent. 8 "Cross-training to a Higher Fitness Level," Helton, Jim 24 "Peaking in the Water? You Bet!," Reeves, Ken 33 Easy Day Workouts "Creative Easy-Day Workouts," Long & Rieken 5 Favorite Workouts "Runners' Favorite Workouts," panel of experienced runners : 12 "Coaches' Favorite Hard-Day Workouts," panel of experienced coaches 13 "Our Favorite Workout," Christopher, Deb 44 Fun Workouts "Distance Runners' Decathlon.tAnderson-Iordan, Teri :..3 "Rambo Run," Weston, Gary 9 "Interesting Summer Work-out5," panel of experienced coaches 10 "Taking the Edge Off Hard Workouts," panel of experienced coaches 15 "Rainbow Relays," Weston, Gary : 18 "Scavenger Hunt," Weston, Gary 19 "IDO Relays," Weston, Gary 20 "Sharks and Guppies," Thompson,. Dale 22 "Rambo Run, Ohio Style," Eleo, Larry 23 "Fun Activity," Lawton, Phil , 26 "Cross Country Flickerball," Thompson, Dale 27 "Halloween Run," Reeves, Ken 28 "Creative Workout," Weitzel, Rich ~ 29 "Spice Up Practice With Wacky Relays," Gerenscer, John ~ - .45 "Pre-Meet-Day Fun-Runs," Klock, Ty -46 i Cross Country Products Available from IDEA, Ine., Publishers of the CROSS COUNTRY JOURNAL AAF/CIF Cross Country Manual (book) Best of the Cross Country Journal, in three volumes (books) Buffaloes, Running with the by Chris Lear (book) Cartoons, The Best of the CCJ, in three sets (loose) CCMEET: the computer program to score actual meets (disc) Coaches' Forum, Fifteen Years of the (book) Coaching Cross Country .. -

Table of Contents

A Column By Len Johnson TABLE OF CONTENTS TOM KELLY................................................................................................5 A RELAY BIG SHOW ..................................................................................8 IS THIS THE COMMONWEALTH GAMES FINEST MOMENT? .................11 HALF A GLASS TO FILL ..........................................................................14 TOMMY A MAN FOR ALL SEASONS ........................................................17 NO LIGHTNING BOLT, JUST A WARM SURPRISE ................................. 20 A BEAUTIFUL SET OF NUMBERS ...........................................................23 CLASSIC DISTANCE CONTESTS FOR GLASGOW ...................................26 RISELEY FINALLY GETS HIS RECORD ...................................................29 TRIALS AND VERDICTS ..........................................................................32 KIRANI JAMES FIRST FOR GRENADA ....................................................35 DEEK STILL WEARS AN INDELIBLE STAMP ..........................................38 MICHAEL, ELOISE DO IT THEIR WAY .................................................... 40 20 SECONDS OF BOLT BEATS 20 MINUTES SUNSHINE ........................43 ROWE EQUAL TO DOUBELL, NOT DOUBELL’S EQUAL ..........................46 MOROCCO BOUND ..................................................................................49 ASBEL KIPROP ........................................................................................52 JENNY SIMPSON .....................................................................................55 -

Sprints & Hurdles

Hurdles Steve Cowburn – 0419 301 412 Hurdles • Theory Session Objectives – Discuss & define stride pattern and rhythm – Discuss stride length & cadence and identify importance – Analyse and identify key actions at various stages of a hurdle race – Analyse required actions for lead & trail leg and arms – Identify common hurdling faults 2 Hurdles Introduction • Hurdling is, because of its technical and energy demands, an exciting and challenging event. The technical component of hurdling is clearly much greater than in sprinting, yet the concept of the hurdles race must be one of a sprint, with adjustment for each hurdle. The stride pattern for sprint hurdling is a 8 stride pattern to the first hurdle followed by a 3 stride pattern between the hurdles 3 Hurdles • The essence of hurdling events is to generate as much speed as possible over the race distance, while clearing a prescribed number of equally spaced barriers of a specific height. As a result the number of strides taken during a race is largely predetermined, as is their length. • The athletes COG is kept as close as possible to it’s normal sprinting path while crossing the hurdles in order to minimize the length of time in the air • The concept of rhythm (a regular pattern of movement rehearsed to be as efficient as possible throughout the race) becomes of utmost importance in a hurdlers preparation 4 Hurdles • Nearly all athletes in a hurdle race will take the same number of strides. • e.g. 80mh = 12m run in, 7m spacings, 12m run out, 9 flights – 8 strides to the first hurdle -

Athletics Is an Exclusive Collection of Sporting Events That Involve Competitive Running, Jumping, Throwing, and Walking. the Mo

Athletics is an exclusive collection of sporting events that involve competitive running, jumping, throwing, and walking. The most common types of athletics competitions are track and field, road running, cross country running, and race walking. The simplicity of the competitions, and the lack of a need for expensive equipment, makes athletics one of the most commonly competed sports in the world. Organised athletics are traced back to the Ancient Olympic Games from 776 BC, and most modern events are conducted by the member clubs of the International Association of Athletics Federations. The athletics meeting forms the backbone of the modern Summer Olympics, and other leading international meetings include theIAAF World Championships and World Indoor Championships, and athletes with aphysical disability compete at the Summer Paralympics and the IPC Athletics World Championships. Etymology The word athletics is derived from the Greek word "athlos" (0șȜȠȢ), meaning "contest" or "task." Initially, the term was used to describeathletic contests in general ± i.e. sporting competition based primarily on human physical feats. In the 19th century in Europe, the term athletics acquired a more narrow definition and came to describe sports involving competitive running, walking, jumping and throwing. This definition continues to be the most prominent one in the United Kingdom and most of the areas of the former British Empire. Furthermore, foreign words in many Germanic and Romance languages which are related to the term athletics also have a similar meaning. In contrast to this, in much of North America athletics is synonymous with athletic sports in general, maintaining a more historic usage of the term. -

The Hurdles - from Start to Finish

THE HURDLES - FROM START TO FINISH By Tom Tellez, Mike Takaha A hurdle race can be described as a sprint with obstacles. To be most efficient, the vertical deviation of the athlete’s center of gravity should be as little as possible when traveling over the hurdles. In order to accomplish this, the athlete must be in the proper position when he or she leaves the ground to take the hurdle. This paper will discuss the hurdle races from start to finish, describing the proper mechanics to be used to achieve maximum results. THE START The Starting Position Use a sprinter’s crouch start, with a “medium” block spacing. The rear knee should be approximately in line with the toe of the front foot (see Diagram 1). The arms should be perpendicular to the ground, with the elbows locked. The head should be in natural alignment with the shoulders, with the eyes focused straight down. The toes of the front foot should be on the ground so that force may be exerted against the track at the gun. The Set Position At the “Set” command, the hips are raised to a position slightly above the shoulders, with the shoulders moving slightly forward, creating an angle in the lead leg of 90° and approximately 130° in the rear knee. The head is kept in natural alignment with the body and the eyes are focused just behind the starting line. Slight pressure is exerted against the rear block (see Diagram 2). The Gun At the “Gun”, the athlete should think only of extension off of the lead block, with active arm action. -

The University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire All You Have

i The University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire All You Have to Do is Go Out and Do Some Four- and Five-Hour Runs: Understanding Wisconsin’s Elite Long Distance Runners, 1975-2011 Department of History By Thomas Breitbach Supervising professor: Joseph Orser Eau Claire, Wisconsin December, 2011 Copyright of this work is owned by the author. This digital version is published by McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, with the consent of the author. ii Table of Contents I. Table of Contents……………………………………………………………….ii II. Abstract………………………….…………………………………...……..…..iii III. Introduction: Why Study Wisconsin’s Elite Distance Runners?..........................1 IV. Background: Training History and America’s Place in the Running World…....4 V. Athlete Profiles a. John Easker: Farm, Run, Sleep, Repeat……………………………….…….13 b. Cathy Branta: Breaking Women’s Sports Barriers and Records……………22 c. Dan Held: You’ll Get There, In the Long Run...............................................26 d. Chris Solinsky: Wisconsin’s Home Grown National Champion……………35 VI. Final Analysis: What Best Have in Common……….…………………………..54 VII. Bibliography……………………………………………………………………..59 VIII. Appendix a. Questionnaire: History of Wisconsin Elite Distance Runner Survey……..…67 iii Abstract The state of Wisconsin has been the home to numerous national and Olympic level track and field athletes during the 20th and early 21st century. National champions of the high school, collegiate and professional ranks hailed from and trained in Wisconsin. In particular, the state has been well represented by long distance runners in national and international competition, especially since the running boom of the 1970s. This paper aims to understand these individuals, their training, and the impacts that the state of Wisconsin, its climate, its training facilities, its culture, and its people, have had on elite level distance runners. -

Specific Features of the Decathlon

S www.verkhoshansky.com S Articles TM SPECIFIC FEATURES OF THE DECATHLON By Prof. Y. Verhoshanski, A. Ushakov, O. Hatshatryan The authors look at the tendencies that occur in the development of explosive power indicators in decathlon training and make suggestions of how to adjust the volume and the sequence the single events are performed in training to the fluctuation in the functional power capacities. The article is a slightly condensed translation from Legkaya Atletika, Moscow, No. 7, July 1987. One of the major factors responsible for the progress in the decathlon appears to be the improvements in the level of specific physical preparation. It is therefore extremely important to establish the specific characteristics required for the preparation by taking a close look at the dynamics of the functional indicators and how they change during a year’s training cycle. LONG TERM TENDENCIES An analysis of the development of leg extensors, arm extensors and ankle flexors shows an uneven power improvement that does not correspond with the progress of the total decathlon scores. This tendency continues up to 6000-6500 points level when all power indicators begin to correlate with performances in the individual events, as well as the total score. The results indicate that the importance of muscular power increases considerably when decathlon performances reach a higher level. At this stage every additional point is achieved by improved power indicators, although the rate development of power in different muscle groups varies considerably during multi-year training processes. The fastest development rate, for example, occurs in arm extensors, the slowest in ankle flexors. -

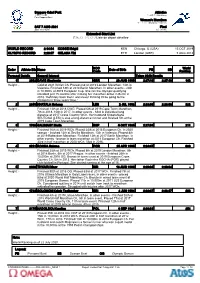

Extended Start List 拡張スタートリスト / Liste De Départ Détaillée

Sapporo Odori Park Athletics 札幌大通公園 陸上競技 / Athlétisme Parc Sapporo Odori Women's Marathon 女子マラソン / Marathon - femmes SAT 7 AUG 2021 Final Start Time 06:00 決勝 / Finale Extended Start List 拡張スタートリスト / Liste de départ détaillée WORLD RECORD 2:14:04 KOSGEI Brigid KEN Chicago, IL (USA) 13 OCT 2019 OLYMPIC RECORD 2:23:07 GELANA Tiki ETH London (GBR) 5 AUG 2012 NOC World Order Athlete Bib Name Code Date of Birth PB SB Ranking Personal Details General Interest Tokyo 2020 Results 1 2002 DAVIS Stephanie GBR 26 AUG 1990 2:27:16 2:27:16 192 Height: - Gold at 2021 British Ch. Placed 2nd at 2019 London Marathon, 14th in Valencia. Finished 18th at 2018 Berlin Marathon. In other events - 24th in 10,000m at 2019 European Cup. She ran the Olympic qualifying standard just 15 months after making her marathon debut in Berlin in 2018. 'Definitely back then I was never thinking I'll be going to the Olympics in three years' time.' 2 2859 KHATALA Neheng LES 2 JUL 1992 2:28:06 2:28:06 322 Height: - Finished 13th at 2018 CWG. Placed 6th at 2019 Cape Town Marathon, 7th in 2018, 10th in 2017. In other events - 83rd in individual long distance at 2017 Cross Country WCh. Her husband Khoarahlane SEUTOALI (LES) is also a long-distance runner and finished 5th at the 2019 Cape Town Marathon. 3 1766 GALIMANY Marta ESP 5 OCT 1985 2:27:08 211 Height: - Finished 16th at 2019 WCh. Placed 24th at 2018 European Ch. In 2020 season - finished 12th at Sevilla Marathon, 13th in Valencia. -

Age Is No Barrier; Karyne Di Marco; Don Quinn; Tom Hancock; Hugh Coogan; Tony Baker

A History of Masters/Veterans Athletics in Australia This page, from top: 3km steeplechasers proving age is no barrier; Karyne Di Marco; Don Quinn; Tom Hancock; Hugh Coogan; Tony Baker. Front cover, from top: Cliff Bould, Jack Pennington, John Gilmour; Peggy MacLiver, Marg Allison; Lyn Ventris; Heather Doherty; Kevin Solomon (yellow singlet, in Lahti field); Marie Kay. AMA History Book 164pp:AMA History Book 164pp 16/03/11 7:16 PM Page I Age is no Barrier A HISTORY of MASTERS/VETERANS ATHLETICS in AUSTRALIA by Bryan Thomas AMA History Book 164pp:AMA History Book 164pp 16/03/11 7:16 PM Page II Age is no Barrier A History of Masters/Veterans Athletics in Australia Author: Bryan Thomas © Australian Masters Athletics Inc, 2011 ISBN: 978-0-9803191-1-8 Material in this publication may be reproduced for the purposes of marketing and promoting Masters Athletics, provided acknowledgement of author and source is given ‘Age is no Barrier – A History of Masters/Veterans Athletics in Australia’ is published by Australian Masters Athletics Inc. 13 Sevenoaks Street, Alexandra Hills, Qld 4161 www.australianmastersathletic.org.au Further copies of this book can be obtained from the AMA Secretary email: [email protected] Printed by: Vanguard Press 26 John Street, Northbridge WA 6003 www:vanguardpress.com.au Edited and designed by: Victor Waters, Presswise Publications Formatting and typesetting: Kathy Nicholas, Elite Typesetting AMA History Book 164pp:AMA History Book 164pp 16/03/11 7:16 PM Page I Age is no Barrier CONTENTS Foreword -

Elite “CUTTING-EDGE” Hurdling by Steve Silvey Assistant Track & Field Coach Sprints/Hurdles/Relays Texas Tech University

Elite “CUTTING-EDGE” Hurdling by Steve Silvey Assistant Track & Field Coach Sprints/Hurdles/Relays Texas Tech University There have been numerous articles written on the subject of proper hurdle technique. Many of these articles have never shared the nuts and bolts of actual hurdle workouts and what elite coaches can do to fine tune their athletes as the prepare for record setting performances. Remember that a great male or female hurdler must spend a lot of time on flexibility. The hurdler should be one of the most flexible athletes on the entire track and field team. Be prepared to stretch twice a day. A tool that can be especially helpful is the Stretch- Rite Belt. It enables the athlete to get the same stretching benefits alone as they do when a coach or second athlete helps them to stretch. Another important component to hurdling is Dorsi-Flexion (heel up-toe toe). Dorsi- Flexion will allow the athlete to gain 2-3 inches in additional “lead leg” clearance and 2-3 inches in “trail leg” clearance. Let’s explore several key factors of hurdle training – specifically 110 meter high hurdle training. 1. Crowding the hurdles together 2. Lowering the hurdle height 3. Removing hurdles in training 4. Increasing attack velocity Crowding the Hurdles Together “Crowding the hurdles” together means moving the hurdles closer together than the original regulation marks on the track. For the men’s 100-meter hurdle it means moving them to a distance of 8.5 meters instead of the normal regulation mark of 9.14 meters. For the women’s 100-meter hurdle it means moving them to a distance of 8.0 – 7.5 meters instead of the normal regulation mark of 8.5 meters. -

Notre Dame Cross Country/Middle Distance Training

Notre Dame Women’s Cross Country/ Middle Distance & Distance Training Tim Connelly Women’s Cross Country and Assistant M&W Track Coach Training based upon: • Sound physiological principles Stress-Recovery-Adaptation/Super-compensation • Experience • Common sense • Individual needs, strengths, weaknesses, etc. • Necessity- sometimes you just need to do what works • Stay HEALTHY • Structured but not “rigid”- Have a plan but adjust as need • Always keep in mind that ultimately we are “training to race” and not “training to have impressive training logs” • Most are “borrowed” ideas (many from people here)- always be willing to learn and adapt I. Summer Preparation • A. Important to begin summer training with break following end of Track season. When summer training begins based on length of track season • B. Emphasis on CONSISTENCY and GRADUAL PROGRESSION • C. Each athlete given own schedule to increase both volume and intensity of training load gradually throughout summer • D. Mileage goals and paces are based on what they have done in the past and long term progression. Conservative with younger runners. • E. Once near 100% volume, will add more intense running to weekly schedule (tempo runs, fartlek, hill repeats). • F. Goal is to be ready to TRAIN well when get to school at end of August, not to be in peak racing shape. • G. Encouraged to run with others (guys) regularly so as not to get too comfortable and develop a false sense of fitness. • H. Lots of emphasis placed on communication, both within the team and with coach to create team atmosphere even before they arrive on campus. Letters, emails, phone calls, texts.