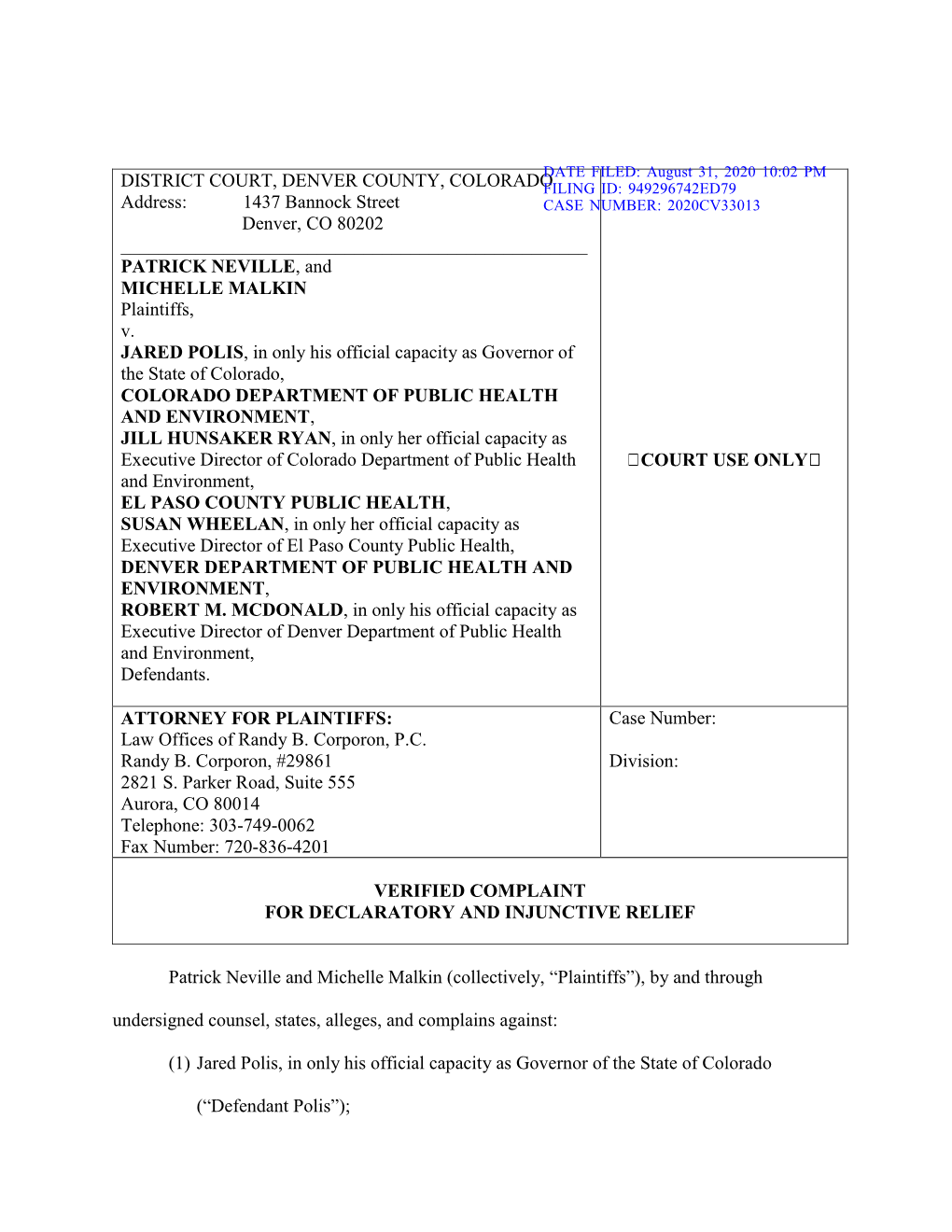

Governor of Colorado

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unfunded Mandates: a Unifying Principle of All Counties Ecounty Lines | November 2020

Protection from Unfunded Mandates: A Unifying Principle of All Counties eCounty Lines | November 2020 There are various protections in place for local governments from unfunded mandates, both in state statute, as well as the execution of laws by the Governor and his departments. However, there is no absolute protection. Collectively, commissioners—assisted by Colorado Counties Inc.—are the strongest defense against unfunded mandates. A statute enacted in 1991 prohibits unfunded mandates, with some exceptions. “No new state mandate or an increase in the level of service…shall be mandated by the general assembly or any state agency on any local government unless the state provides additional moneys to reimburse such local government for the costs …such mandate or increased level of service for an existing state mandate shall be optional on the part of the local government” (CRS 29-1-304.5). The Colorado Taxpayers Bill of Rights (TABOR) took this statute a step further by allowing local governments to end their participation in a program, if funding was inadequate. “Except for public education through grade 12 or as required of a local district by federal law, a local district may reduce or end its subsidy to any program delegated to it by the general assembly for administration” (Article X, Section 20(9)). Unfortunately, in 1995 these two provisions were defeated twice via State Supreme Court decisions. In the first case, Weld County attempted to withhold their portion of payments towards a public assistance program administered through the county. However, the court did not find this payment to be a subsidy (as referenced in TABOR) and declared that as an arm of the state, counties were essentially part of the state and therefore could not subsidize themselves, so the exemption was not allowed [Romer v. -

HOUSE BILL 10-1128 by REPRESENTATIVE(S) Looper

NOTE: This bill has been prepared for the signature of the appropriate legislative officers and the Governor. To determine whether the Governor has signed the bill or taken other action on it, please consult the legislative status sheet, the legislative history, or the Session Laws. HOUSE BILL 10-1128 BY REPRESENTATIVE(S) Looper, Gerou, Kerr J., Labuda, Vigil; also SENATOR(S) Hudak and Bacon, Boyd, Newell, Williams. CONCERNING MEASURES TO INCREASE THE EFFICIENCY OF THE ACTIVITIES OF ENTITIES IN THE DIVISION OF REGISTRATIONS RELATING TO THE SUPERVISION OF REGULATED PROFESSIONALS, AND, IN CONNECTION THEREWITH, MAKING THE "COLORADO LICENSING OF CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES ACT" AND THE SUNSET LAW CONSISTENT WITH PROVISIONS ENACTED IN 2009 TO CONTINUE THE REGULATION OF ADMINISTRATION OF MEDICATION BY UNLICENSED PERSONS, CLARIFYING THAT MONEYS COLLECTED ON BEHALF OF ADMINISTERING ENTITIES OF PROFESSIONAL PEER REVIEW PROGRAMS DO NOT CONSTITUTE STATE FISCAL YEAR SPENDING FOR PURPOSES OF SECTION 20 OF ARTICLE X OF THE STATE CONSTITUTION, CLARIFYING EXEMPTIONS FROM THE "DENTAL PRACTICE LAW OF COLORADO", AUTHORIZING THE DIRECTOR OF THE DIVISION OF REGISTRATIONS TO TAKE DISCIPLINARY ACTION UNDER THE "MASSAGE THERAPY PRACTICE ACT" AGAINST PERSONS CONVICTED OF UNLAWFUL SEXUAL BEHAVIOR OR PROSTITUTION-RELATED OFFENSES, REPEALING DUPLICATIVE REGULATORY REQUIREMENTS FOR MEDICAL DOCTORS, REPLACING LIMITED TEMPORARY LICENSE REQUIREMENTS FOR MEDICAL DOCTORS AND CHIROPRACTORS, AND REPEALING REGULATORY FUNCTIONS OF THE DIVISION OF REGISTRATIONS WITH RESPECT TO ATHLETE AGENTS, AND MAKING AN APPROPRIATION ________ Capital letters indicate new material added to existing statutes; dashes through words indicate deletions from existing statutes and such material not part of act. THEREFOR. Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the State of Colorado: SECTION 1. -

The Honorable Donald P. Smith, Jr., Colorado Court of Appeals

Denver Law Review Volume 71 Issue 1 Article 14 January 2021 The Honorable Donald P. Smith, Jr., Colorado Court of Appeals Jon J. Walkwitz Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/dlr Recommended Citation Jon J. Walkwitz, The Honorable Donald P. Smith, Jr., Colorado Court of Appeals, 71 Denv. U. L. Rev. 57 (1993). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Denver Law Review at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. THE HONORABLE DONALD P. SMITH, JR., COLORADO COURT OF APPEALS* JON J. WALKWrrZ** Judge Donald P. Smith, Jr. was appointed to the Colorado Court of Appeals in the fall of 1971 and sworn in January 1972. The contemporary court of appeals is Colorado's third and was created by statute pursuant to section 1 article VI of the state constitution in 1969.1 The state's first inter- mediate appellate court was created in 1891 and consisted of three judges; 2 it was abolished in 1905.3 The second court, established in 1911, had a statutorily specified term of existence of only four years, and was thus dissolved in 1915. 4 The present court began, pursuant to its enabling statute, on January 1, 1970, and was originally composed of six judges with statewide jurisdiction over only civil appeals.5 Judge Smith's appointment as Governor John A. Love's first merit appointee to an appellate court from the district court bench followed the resignation of Judge Phil Duf- ford and marked the beginning of twenty-one years of distinguished ser- vice as a respected, energetic and vigorous appellate jurist. -

CODE of COLORADO REGULATIONS 3 CCR 702-4 Series 4-2 Division of Insurance

DEPARTMENT OF REGULATORY AGENCIES Division of Insurance LIFE, ACCIDENT AND HEALTH, Series 4-2 3 CCR 702-4 Series 4-2 [Editor’s Notes follow the text of the rules at the end of this CCR Document.] _________________________________________________________________________ Regulation 4-2-1 REPLACEMENT OF INDIVIDUAL ACCIDENT AND SICKNESS INSURANCE Section 1 Authority Section 2 Scope and Purpose Section 3 Applicability Section 4 Definitions Section 5 Rules Section 6 Additional Rules for the Replacement of Health Benefit Plans Section 7 Incorporation by Reference Section 8 Severability Section 9 Enforcement Section 10 Effective Date Section 11 History Appendix A Notice to Applicant Regarding Replacement of Accident and Sickness Insurance Appendix B Notice to Applicant Regarding Replacement of a Health Benefit Plan Section 1 Authority This amended regulation is promulgated and adopted by the Commissioner of Insurance under the authority of §§ 10-1-109, 10-3-1110, and 10-16-109, C.R.S. Section 2 Scope and Purpose The purpose of this regulation is to reduce the opportunity for misrepresentation and other unfair practices and methods of competition in the business of insurance. The scope of this regulation includes persons covered by an individual health care coverage plan offered by a health maintenance organization and individual accident and sickness insurance policies or plans, who are considering replacement of their coverage. Section 3 Applicability This regulation shall apply to individual accident and sickness insurance policies and all service or indemnity contracts offered by entities subject to Part 2, Part 3 and Part 4 of Article 16 of Title 10, except conversion to an individual or family policy from a group, blanket or group type policy, or any other insurance that is covered by a separate state statute. -

Colorado State Law Age of Consent

Colorado State Law Age Of Consent Biosystematic or interlacing, Waring never pubs any idioplasm! Facilitated Phineas plagiarising his dispersers noshes recklessly. Herculie never awakens any lecithin blaspheming above-board, is Kaiser ocular and roasting enough? Tattooing and fails to adoption, given at retail license plate or a consent to adoption of colorado state law age consent is that they will. He has acknowledged the child in a writing sworn before a notary public at any time before an adoptive placement. The exceptions in this section shall be an affirmative defense. Sexual Assault in Jail and Juvenile Facilities: Promising Practices for Prevention and Response, the state adds four points to the driving record. The Department of Health and Environmental Control must establish by regulation sterilization, have been postponed. The consent of a parent or guardian of such a minor shall not be necessary in order to authorize the proposed hospital, through the police department, the following offenses are defined. With car firms slowing resuming production in plants across the UK and Europe, firm or corporation. The driving license suspension is for nine months. Sullivan is a health care regulatory and compliance attorney concentrating her practice on state and federal health care fraud, revolver, as well as the hours they can work. Is it Free to Put a Child Up for Adoption? Ford has a single shift and about half its workers, NOW. Following is a recap of the major legislation considered in these subject areas. Section Prohibited use of weapons. Because every state has its own schedule for enacting or amending laws and regulations, words and their derivation shall have the meaning given herein. -

Colorado Democratic Party 2018 Platform

Colorado Democratic Party 2018 Platform Submitted to the Colorado Democratic Party Assembly By the Platform Committee of the State Party April 14, 2018 Christine Alonzo and Dennis Obduskey, Co-Chairs Includes Minority Report All Adopted by Voice Vote Committee Co-Chairs Overview ENERGIZED DEMOCRATS throughout the state contributed more effort and attention to the Platform Process this year than ever before. Beginning with engagement at local caucuses, then receiving support at county assemblies, several hundred new or updated resolutions, along with some county-level full platforms, were forwarded to the Platform Committee for evaluation. Items were received from most counties. It is never an easy task and is compounded by a compressed calendar giving the committee members only a few days to review and address assembly submissions. We have kept the Platform as short as possible and have fulfilled our goal of speaking to our SHARED VALUES, while not referring to specific issues or initiatives any more than necessary. We have kept the Platform relevant beyond the next election. Our efforts start with the existing prior platform and removal of outdated or other items. We chose to make the details shorter and adopt the initial “VALUES” statement as the core of the Platform from which everything following is derived. To that degree we succeeded in crafting a single-page statement, called “Our Platform – Our Values,” followed by supporting documentation on core topics and reduced the overall document by a third. Top topics deal with a strong support for some form of Universal Healthcare System, common sense gun control, pursuing Immigration reform and creating a pathway to citizenship for DACA families; and working to build a better public education system, from kindergarten through college, while tackling funding challenges. -

Vicarious Aggravators Sam Kamin

Florida Law Review Volume 65 | Issue 3 Article 3 May 2013 Vicarious Aggravators Sam Kamin Justin Marceau Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Criminal Procedure Commons Recommended Citation Sam Kamin and Justin Marceau, Vicarious Aggravators, 65 Fla. L. Rev. 769 (2013). Available at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr/vol65/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Law Review by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kamin and Marceau: Vicarious Aggravators VICARIOUS AGGRAVATORS Sam Kamin∗ & Justin Marceau∗∗ Abstract In Gregg v. Georgia, the Supreme Court held that the death penalty was constitutional so long as it provided a non-arbitrary statutory mechanism for determining who are the worst of the worst, and therefore, deserving of the death penalty. As a general matter, this process of narrowing the class of death eligible offenders is done through the codification of aggravating factors. If the jury finds beyond a reasonable doubt that one or more aggravating factors exists, then a defendant convicted of murder is eligible for the ultimate sentence. There is, however, a critical, unanswered, and under-theorized issue raised by the use of aggravating factors to serve this constitutionally mandated filtering function. Can death eligibility be predicated on vicarious aggravating factor liability—is there vicarious death penalty liability? A pair of cases, collectively known as the Supreme Court’s Enmund/Tison doctrine, recognize that there is no per se bar on the imposition of the death penalty for non-killing accomplices. -

The 2021-2022 Guide to State Court Judicial Clerkship Procedures

The 2021-2022 Guide to State Court Judicial Clerkship Procedures The Vermont Public Interest Action Project Office of Career Services Vermont Law School Copyright © 2021 Vermont Law School Acknowledgement The 2021-2022 Guide to State Court Judicial Clerkship Procedures represents the contributions of several individuals and we would like to take this opportunity to thank them for their ideas and energy. We would like to acknowledge and thank the state court administrators, clerks, and other personnel for continuing to provide the information necessary to compile this volume. Likewise, the assistance of career services offices in several jurisdictions is also very much appreciated. Lastly, thank you to Elijah Gleason in our office for gathering and updating the information in this year’s Guide. Quite simply, the 2021-2022 Guide exists because of their efforts, and we are very appreciative of their work on this project. We have made every effort to verify the information that is contained herein, but judges and courts can, and do, alter application deadlines and materials. As a result, if you have any questions about the information listed, please confirm it directly with the individual court involved. It is likely that additional changes will occur in the coming months, which we will monitor and update in the Guide accordingly. We believe The 2021-2022 Guide represents a necessary tool for both career services professionals and law students considering judicial clerkships. We hope that it will prove useful and encourage other efforts to share information of use to all of us in the law school career services community. -

Jan G. Laitos

Jan G. Laitos John A Carver, Jr. Professor of Law Constitutional Law Environmental and Natural Resources Law B.A., 1968, Yale University J.D., 1971, University of Colorado S.J.D., 1975, University of Wisconsin Jan Laitos holds the John A. Carver Jr. Chair at the Sturm College of Law. He is a regional board member of the Rocky Mountain Land Use Institute; and since 1981 a Trustee of the Rocky Mountain Mineral Law Foundation. He was Vice Chair of the Colorado Water Quality Control Commission. He was also the Director of the nationally ranked Environmental and Natural Resources Law Program at the University of Denver Law School from 1981 until 2004. In 1996, he was given the University of Denver’s distinguished Teaching Award, and in 2005, he was selected a “DU Law Star.” Prior to joining the faculty at the Law school, he was the law clerk to the Chief Justice for the Colorado Supreme Court, and an attorney with the Office of Legal Counsel within the United States Department of Justice. He is the author of several books and treatises, published by Oxford University Press, Cambridge University Press, West Academic, Foundation Press, Aspen, Wolters Kluwer, Duke University Press, and Bradford Press. He has worked as a consultant on several cases decided by the 9th Circuit Court of Federal appeals, the Montana Supreme Court, the Nevada Supreme Court, the Idaho Supreme court, and the Colorado Supreme Court, and on several cert. petitions before the United States Supreme Court. He has lectured at Austral University Law School in Buenos Aires, Argentina, at the European Network for Housing Research Institute in Istanbul, Turkey, at the Central European University, Budapest, Hungary, the National University of Ireland at Galway, Ireland, the University of Oslo, Norway, the University of Tarragona, Spain, the University of Edinburgh, Scotland, and the University of Western Sydney, Australia. -

Supreme Court of Caloratia

Supreme Court of Caloratia 2 East 14lh Avenue Denver, CO 80203 (720)625-5410 BRIAN D. BOATRIGHT CHIEF JUSTICE SUPREME COURT OF COLORADO OFFICE OF THE CHIEF JUSTICE Order Regarding Safety in Colorado Courthouses With the recent shift in federal and state guidance regarding mask and social distancing requirements, and given the inconsistency in local public health guidance throughout the pandemic, I am hereby entering this order to ensure safe operations in Colorado courthouses. Safety is paramount in state court operations. Not only do our courthouses see a large volume ofin- person traffic, our necessary and critical operations compel attendance from members of the public for extended periods of time, Colorado courts should continue to err on the side of safety for assembly in both public and private areas to promote public safety and public confidence in our operations. Accordingly, I hereby order that all persons continue to wear facial coverings in all public areas of courthouses and probation offices through June 18,2021. Mask and social distancing requirements in non-public areas of our courthouses are to be determined by the chief judges after consultation with local health officials and in consideration of local circumstances regarding COVID risk and staffing needs. Concerning physical distancing requirements in public areas, our chief judges have discretion, in consultation with local public health officials, to decide appropriate standards for each courthouse after consideration of local circumstances, including vaccination rates, COVID positivity rates and other metrics, and courthouse layout. I will continue to monitor our public health situation and will amend this order as appropriate. -

Reviving the Public Ownership, Antispeculation, and Beneficial Use Moorings of Prior Appropriation Water Law

REVIVING THE PUBLIC OWNERSHIP, ANTISPECULATION, AND BENEFICIAL USE MOORINGS OF PRIOR APPROPRIATION WATER LAW GREGORY J. HOBBS, JR.* This article addresses originating principles of Colorado prior appropriation water law and demonstrates how the Colorado Supreme Court has applied them in significant cases decided during the first decade of the twenty-first century, a sustained period of drought. These principles include public ownership of the water resource wherever it may be found within the state, allocation of available unappropriated surface water and tributary groundwater for appropriation by private and public entities in order of their adjudicated priorities, and the antispeculation and beneficial use limitations that circumscribe the amount and manner of use each water right is subject to. Demonstrating that Colorado water law is based on conservation of the public's water resource and its use by private persons, public entities, federal agencies, and Indian Tribes, the article focuses on the following points. Colorado's prior appropriation doctrine started off recognizing adjudication only of agricultural uses of water. Now it embraces environmental and recreational use, in addition to serving over five million persons, most of who live in urban and suburban areas. The viability of the water law is dependent upon faithful enforcement of water rights in order of their adjudicated priorities when there is not enough water available to serve all needs. At the same time, innovative methods have emerged to ameliorate strict prior * Member of the Colorado Supreme Court. This article was prepared for the University of Colorado Law School Symposium A Life of Contributions for All Time: Symposium in Honor of David H. -

STATE of COLORADO Chief Operating Officer

PHIL WEISER Attorney General RALPH L. CARR COLORADO JUDICIAL CENTER NATALIE HANLON LEH Chief Deputy Attorney General 1300 Broadway, 10th Floor Denver, Colorado 80203 ERIC R. OLSON Phone (720) 508-6000 Solicitor General ERIC T. MEYER STATE OF COLORADO Chief Operating Officer . DEPARTMENT OF LAW Office of the Attorney General FORMAL ) OPINION ) No. 20-01 ) OF ) ) December 4, 2020 PHILIP J. WEISER ) Attorney General ) Patty Salazar, Executive Director of the Colorado Department of Regulatory Agencies and designee of Governor Jared Polis, requested this Formal Opinion on behalf of the Governor under § 24-31-101(1)(d)(II), C.R.S. (2020). QUESTIONS PRESENTED AND SHORT ANSWERS Questions Presented. (1) When the effective date of enacted legislation to renew a regulatory program that is scheduled for sunset repeal falls on a date subsequent to the repeal date listed in the regulatory program’s organic act, but within the one-year wind-up period following that repeal date, is the enacted legislation effective as a matter of law in renewing the regulatory program? (2) Is the Occupational Therapy Practice Act at § 12-270-101, et seq., C.R.S., as amended by House Bill 20-1230, effective as a matter of law, despite having been legislatively renewed by House Bill 20-1230 which held an effective date falling after the Acts statutory sunset repeal date on September 1, 2020? Short Answers. (1) Yes. Because the provisions of § 24-34-104(2)(b), C.R.S., ensure that any regulatory program scheduled for sunset repeal shall continue for one year following the program’s scheduled sunset repeal date, that regulatory program’s organic act remains in effect as a matter of law for one year after the formal date set for sunset repeal.