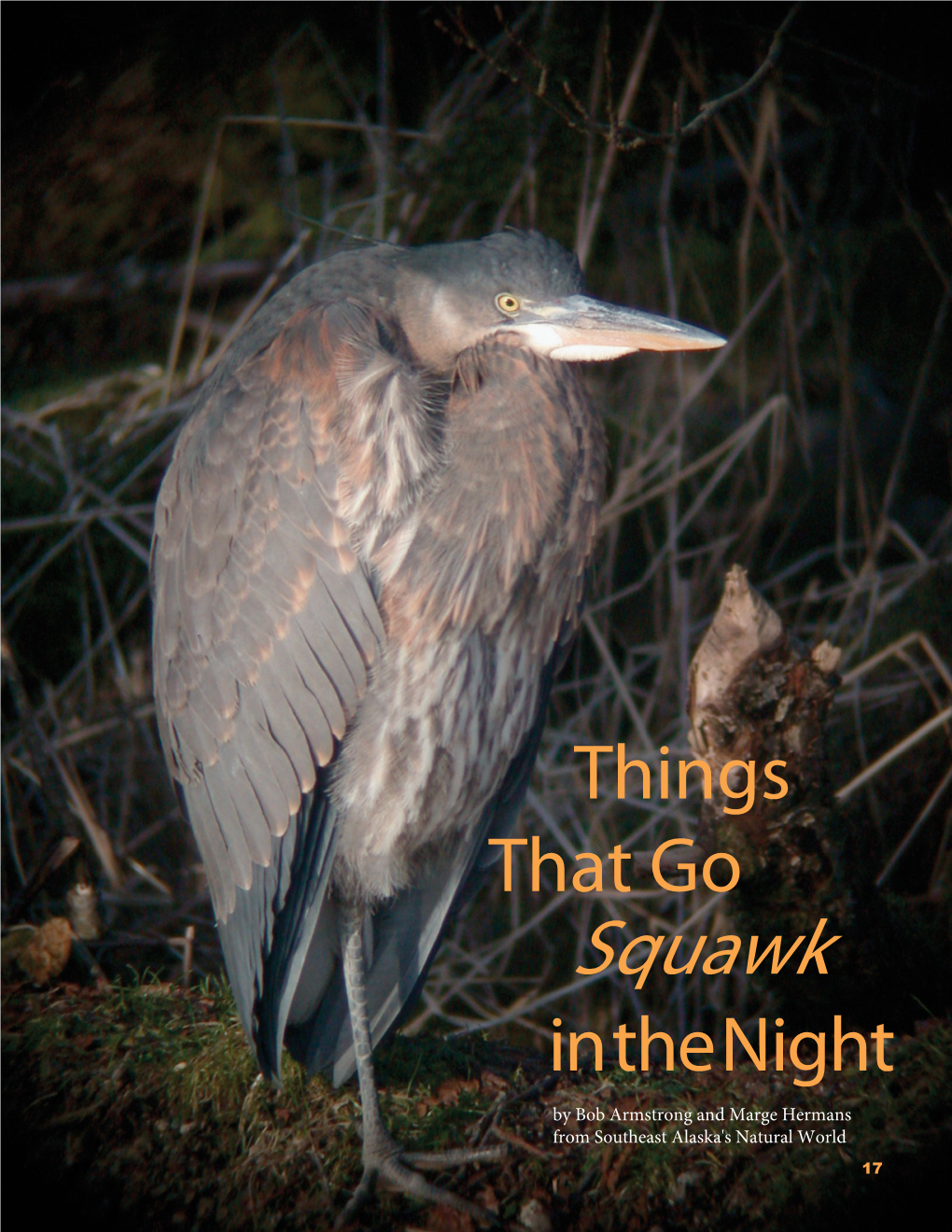

Things That Go Squawk in the Night (Great Blue Herons)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution of Body Shape in Haida Gwaii Three-Spined Stickleback

Journal of Fish Biology (2007) 70, 1484–1503 doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2007.01425.x, available online at http://www.blackwell-synergy.com 10 000 years later: evolution of body shape in Haida Gwaii three-spined stickleback M. A. SPOLJARIC AND T. E. REIMCHEN* Department of Biology, University of Victoria, Victoria BC V8X 4A5, Canada (Received 29 April 2006, Accepted 23 December 2006) The body shape of 1303 adult male three-spined stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus from 118 populations on Haida Gwaii archipelago off the mid-coast of British Columbia was investigated using discriminant function analysis on partial warp scores generated from 12 homologous landmarks on a digital image of each fish. Results demonstrated geographical differences in adult body shape that could be predicted by both abiotic and biotic factors of the habitat. Populations with derived shape (CV1À), including thick peduncles, posterior and closely spaced dorsal spines, anterior pelvis, small dorsal and anal fins, were found in small, shallow, stained ponds, and populations with less derived shape (CV1þ), with small narrow peduncles, anterior and widely spaced dorsal spines, posterior pelvis, large dorsal and anal fins were found in large, deep, clear lakes. This relationship was replicated between geographic regions; divergent mtDNA haplotypes in lowland populations; between predation regimes throughout the archipelago, and in each geographical region and between predation regimes in lowland populations monomorphic for the Euro and North American mtDNA haplotype. There were large-bodied populations with derived shape (CV2À), including small heads and shallow elongate bodies in open water habitats of low productivity, and populations with smaller size and less derived shape (CV2þ), with large heads and deeper bodies in higher productivity, structurally complex habitats. -

Owls-Of-Nh.Pdf

Lucky owlers may spot the stunning great gray owl – but only in rare years when prey is sparse in its Arctic habitat. ©ALAN BRIERE PHOTO 4 January/February 2009 • WILDLIFE JOURNAL OWLSof NEW HAMPSHIRE Remarkable birds of prey take shelter in our winter woods wls hold a special place in human culture and folklore. The bright yellow and black eyes surrounded by an orange facial disc Oimage of the wise old owl pervades our literature and conjures and a white throat patch. up childhood memories of bedtime stories. Perhaps it’s their circular Like most owls, great horned owls are not big on building their faces and big eyes that promote those anthropomorphic analogies, own nests. They usually claim an old stick nest of another species or maybe it is owls’ generally nocturnal habits that give them an air – perhaps one originally built by a crow, raven or red-tailed hawk. In of mystery and fascination. New Hampshire, great horned owls favor nest- New Hampshire’s woods and swamps are ing in great blue heron nests in beaver-swamp home to several species of owls. Four owl spe- BY IAIN MACLEOD rookeries. Many times, while checking rooker- cies regularly nest here: great horned, barred, ies in early spring, I’ll see the telltale feather Eastern screech and Northern saw-whet. One other species, the tufts sticking up over the edge of a nest right in the middle of all long-eared owl, nests sporadically in the northern part of the state. the herons. Later in the spring, I’ll return and see a big fluffy owlet None of these species is rare enough to be listed in the N.H. -

Teleostei, Syngnathidae)

ZooKeys 934: 141–156 (2020) A peer-reviewed open-access journal doi: 10.3897/zookeys.934.50924 RESEARCH ARTICLE https://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Hippocampus nalu, a new species of pygmy seahorse from South Africa, and the first record of a pygmy seahorse from the Indian Ocean (Teleostei, Syngnathidae) Graham Short1,2,3, Louw Claassens4,5,6, Richard Smith4, Maarten De Brauwer7, Healy Hamilton4,8, Michael Stat9, David Harasti4,10 1 Research Associate, Ichthyology, Australian Museum Research Institute, Sydney, Australia 2 Ichthyology, California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco, USA 3 Ichthyology, Burke Museum, Seattle, USA 4 IUCN Seahorse, Pipefish Stickleback Specialist Group, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada5 Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa 6 Knysna Basin Project, Knysna, South Africa 7 University of Leeds, Leeds, UK 8 NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia, USA 9 University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW, Australia 10 Port Stephens Fisheries Institute, NSW, Australia Corresponding author: Graham Short ([email protected]) Academic editor: Nina Bogutskaya | Received 13 February 2020 | Accepted 12 April 2020 | Published 19 May 2020 http://zoobank.org/E9104D84-BB71-4533-BB7A-2DB3BD4E4B5E Citation: Short G, Claassens L, Smith R, De Brauwer M, Hamilton H, Stat M, Harasti D (2020) Hippocampus nalu, a new species of pygmy seahorse from South Africa, and the first record of a pygmy seahorse from the Indian Ocean (Teleostei, Syngnathidae). ZooKeys 934: 141–156. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.934.50924 Abstract A new species and the first confirmed record of a true pygmy seahorse from Africa,Hippocampus nalu sp. nov., is herein described on the basis of two specimens, 18.9–22 mm SL, collected from flat sandy coral reef at 14–17 meters depth from Sodwana Bay, South Africa. -

Esox Lucius) Ecological Risk Screening Summary

Northern Pike (Esox lucius) Ecological Risk Screening Summary U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, February 2019 Web Version, 8/26/2019 Photo: Ryan Hagerty/USFWS. Public Domain – Government Work. Available: https://digitalmedia.fws.gov/digital/collection/natdiglib/id/26990/rec/22. (February 1, 2019). 1 Native Range and Status in the United States Native Range From Froese and Pauly (2019a): “Circumpolar in fresh water. North America: Atlantic, Arctic, Pacific, Great Lakes, and Mississippi River basins from Labrador to Alaska and south to Pennsylvania and Nebraska, USA [Page and Burr 2011]. Eurasia: Caspian, Black, Baltic, White, Barents, Arctic, North and Aral Seas and Atlantic basins, southwest to Adour drainage; Mediterranean basin in Rhône drainage and northern Italy. Widely distributed in central Asia and Siberia easward [sic] to Anadyr drainage (Bering Sea basin). Historically absent from Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean France, central Italy, southern and western Greece, eastern Adriatic basin, Iceland, western Norway and northern Scotland.” Froese and Pauly (2019a) list Esox lucius as native in Armenia, Azerbaijan, China, Georgia, Iran, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Albania, Austria, Belgium, Bosnia Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Moldova, Monaco, 1 Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, Ukraine, Canada, and the United States (including Alaska). From Froese and Pauly (2019a): “Occurs in Erqishi river and Ulungur lake [in China].” “Known from the Selenge drainage [in Mongolia] [Kottelat 2006].” “[In Turkey:] Known from the European Black Sea watersheds, Anatolian Black Sea watersheds, Central and Western Anatolian lake watersheds, and Gulf watersheds (Firat Nehri, Dicle Nehri). -

Nature at Saddlebrook Resort &

Saddlebrook Resort is nestled on 480 acres of a gated, secure Florida nature SADDLEBROOK RESORT preserve. As guests walk, jog, or bike along pathways of the resort, they take in our beautiful tropical setting abounding in wildlife, flora, and fauna. Myriad species of exotic, striking birds; interesting lizards, turtles, frogs, and NATURE WALK gators; colorful, fragrant flowers; lush landscaping, and verdant vegetation coexist in perfect harmony. Fresh, pure air and the resort’s pristine natural Map & Guide layout beckon guests to explore and convene with the elements. Please adventure in our great outdoors appreciating breath-taking wonders. Along Saddlebrook Resort is home to with the highlights of nature described by the numerical legend indicated along the areas of this guide, discover many other creatures and experience an abundance of Florida wildlife and vegetation. nuances of peaceful loveliness found throughout Saddlebrook. Enjoy! 6 1 2 3 4 5 5700 Saddlebrook Way Wesley Chapel, Florida 33543-4499 813/973-1111 800/729-8383 Fax 813/973-4504 www.saddlebrookresort.com 1 1 Sandhill Cranes: These birds have 2 American Alligator: Once nearly 1 Love Bugs: Usually, Love Bugs are a body length just over 3 ft. long and a extinct, Alligators have made a dramatic 2 Locusts: These Locusts are better known seen in Florida in the late spring and wingspan of 6 ft. Sandhill Cranes are comeback in recent years due to protective 3 as Lubber Grasshoppers. In our area, they then again in the late summer. They can predominately grey. The Florida sub-species 6 laws. Nearly every pond at Saddlebrook 4 are mostly yellow but bear red and black also be seen in South Florida in smaller is a year-round resident in freshwater marshes, hosts one. -

Wetland Wildlife Cards

Wetland wildlife cards • To make the cards, cut the line across the width of your paper then fold each half in half again so you end up with a picture on one side and the information on the other. Stick the two sides together with glue. Cut Fold Fold Stickleback Diet: Insects, crustaceans, tadpoles and smaller fish Wetland adaptations: Some sticklebacks have adapted to be able to cope with both fresh and saltwater meaning they can live in both rivers and the sea Classification: Vertebrate - Fish Habitat: Ponds, lakes, ditches and rivers Did you know? The male develops a bright red throat and belly and performs a courtship dance to attract a mate. The male also builds and protects the nest Cut Cut Eel Diet: Plants, dead animals, fish eggs, invertebrates and other fish Wetland adaptations: Long, narrow body enables it to get into crevices Classification: Vertebrate - Fish Habitat: Rivers and ditches Did you know? Adult eels migrate 3,000 miles (4,800 km) to the Sargasso Sea to spawn. It then takes the young eels two or three years to drift back to their homes here in the UK Fold Fold Smooth newt Diet: Insects, caterpillars, worms and slugs while on land; crustaceans, molluscs and tadpoles when in the water Wetland adaptations: Can breathe through their skin Classification: Vertebrate - Amphibian Habitat: Ponds in spring; woodland, grassland, hedgerows and marshes in summer and autumn; hibernates underground, among tree roots and under rocks and logs over winter Did you know? Their body gives out a poisonous fluid when they feel threatened -

GREAT BLUE HERON (Ardea Herodias)

GREAT BLUE HERON Oneida Lake Status: (Ardea herodias) Common • Largest heron in North America • Often found in shallow water looking for food • Strongly affected by human contact The great blue heron is the largest heron in North America, with a wingspan as large as 84 inches and weighing up to 7 pounds. Adults have bluish gray wings and white heads decorated by a black streak above the eye. They have long Great blue heron in the wild necks streaked with white, brown, and black, and a long yellow beak that tapers to a point. Heron legs are long, thin, and greenish-yellow in color. Great blue herons can be found in marshes and swamps (including Cicero Swamp), flooded meadows, and along Oneida Lake’s shallow water shoreline, but they always Great blue herons boast a large live near water. Herons forage wingspan when flying while standing in water, and are most active around dawn and dusk. They locate their food by sight, and spear prey with their long, sharp bill. Using this method, herons eat fish, frogs, insects, snakes, turtles, Note the distinctive bill, and “S” rodents and small birds. Herons shaped neck (www.sfwmd.gov/org/erd/krr) swallow their prey whole, and have been known to choke on prey that is too large. Great blue herons nest in trees and bushes, where they build Wading through water, searching for a bulky stick nests. Often, they will form colonies with other meal heron species. When driving on NYS Route 298 through Cicero Swamp, heron nests can be spotted in the trees on the Prepared by: east side of the road. -

Effects of Nesting Bald Eagles (Haliaeetus Leucocephalus) On

Note Effects of Nesting Bald Eagles ( Haliaeetus leucocephalus ) on Behaviour and Reproductive Rates in a Great Blue Heron ( Ardea herodias ) Colony in Ontario BILL THOMpSON 93 Donald Street, Barrie, Ontario L4N 1E6 Canada; email: [email protected] Thompson, Bill. 2017. Effects of nesting Bald Eagles ( Haliaeetus leucocephalus ) on behaviour and reproductive rates in a Great Blue Heron ( Ardea herodias ) colony in Ontario. Canadian Field-Naturalist 131(4): 369 –371. https://doi.org/10.22621/ cfn.v131i4.1848 Bald Eagles ( Haliaeetus leucocephalus ) and Great Blue Herons ( Ardea herodias ) are known to occasionally nest in mixed colonies, even though the former is one of the primary predators of the latter. I observed the two species in four heron colonies near Lake Simcoe, Ontario during two field seasons to assess whether rates of heron chick mortality or nest abandonment were greater in a colony that supported a nesting pair of Bald Eagles than in three nearby single-species colonies. I assessed the effects of eagle presence on heron behaviour using heron movement rates, the number of heron sentries left in colonies during the nesting period, heron nest mortality rates, and the average number of successfully fledged herons per nest. There was no statistically significant difference in movement rate among the four colonies, proportion of birds remaining as sentries, nor nest mortality rates. However, nests in the mixed colony successfully fledged significantly more heron young per nest than did nests in the single-species colonies. The mixed colony was located in a wetland and open lake system that provided extensive foraging habitat and an abundance of the preferred fish prey species of both Great Blue Herons and Bald Eagles, thus reducing predation pressure on the herons. -

Nesting of the Great Blue Heron in Montana

252 CA•RoN,Nesting o[ GreatBlue Heron. [July[Auk Some thirty thousandpersons, it is estimated,viewed the fire, and a largenumber of themsaw the birds,but probablyvery few appreciatedthe opportunity that was offered them of lookingbehind the dark curtain which so persistentlyshrouds one of nature's greatestmysteries, or realizedthat what they saw was,literally aswell as figuratively, 'some light on nightmigration.' NESTING OF THE GREAT BLUE HERON IN MONTANA. BY E. S. CAMERON. Plates IV and V. SINCEliving near the YellowstoneI haveoften wondered where the Great Blue Herons(Ardea herodias) nested which flew up and down the river, or stoodmotionless on the sandbarsintercepting its brown flood. The differentferrymen, on being questioned, saidthe birdspassed and repassed daily, but couldsupply no infor- mationas to their breedinghaunts. Mr. A. C. Giffordof Fallon informedme that he recollectedwhen there were twenty nestsin somecottonwoods about two miles below his property,but was doubtfulif heronsbred there in recentyears, and Mr. Dan Bowman had known of one nest on the Powder River in a cottonwood close to his ranch. Thesewere my onlyrecords. Accordingly,on May 30 my wifeand I rodeto the groveindicated by Mr. Giffordand madea thoroughinvestigation, which proved a taskof somediffi- culty on accountof the thick underbrushof wild roses,willows, and bulberrybushes, concealing regular pitfalls, through which a horsecould scarcely force its way. Part of the woodwas made intoan islandby a smallbranch of the river(called here a slough), and two pairsof Blue-wingedTeal, evidentlynesting, were seen, THE AUK, VOL. XXIII. PLATE V. FIG. 1.--SITE OF GREAT BLUE HERONRY, YELLOWSTONEI{IVER, MONTANA. The nests •re nearly concealed by the thick foliage. -

An Assessment of the Bald Eagle and Great Blue Heron Breeding

William & Mary logo W&M ScholarWorks CCB Technical Reports Center for Conservation Biology (CCB) 2018 An assessment of the Bald Eagle and Great Blue Heron breeding populations along High Rock, Tuckertown, Narrows, and Falls Reservoirs in central North Carolina: 2016 breeding season B. J. Paxton The Center for Conservation Biology, [email protected] B. D. Watts The Center for Conservation Biology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/ccb_reports Recommended Citation Paxton, B. J. and B. D. Watts. 2017. An assessment of the Bald Eagle and Great Blue Heron breeding populations along High Rock, Tuckertown, Narrows, and Falls Reservoirs in central North Carolina: 2017 breeding season. Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series, CCBTR-17-15. College of William and Mary/Virginia Commonwealth University, Williamsburg, VA. 63 pp. This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Conservation Biology (CCB) at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in CCB Technical Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ASSESSMENT OF THE BALD EAGLE AND GREAT BLUE HERON BREEDING POPULATIONS ALONG HIGH ROCK, TUCKERTOWN, NARROWS, AND FALLS RESERVOIRS IN CENTRAL NORTH CAROLINA: 2017 BREEDING SEASON THE CENTER FOR CONSERVATION BIOLOGY AT THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY & VIRGINIA COMMONWEALTH UNIVERSITY AN ASSESSMENT OF THE BALD EAGLE AND GREAT BLUE HERON BREEDING POPULATIONS ALONG HIGH ROCK, TUCKERTOWN, NARROWS, AND FALLS RESERVOIRS IN CENTRAL NORTH CAROLINA: 2017 BREEDING SEASON Barton J. Paxton Bryan D. Watts, PhD Center for Conservation Biology College of William & Mary Virginia Commonwealth University Williamsburg, VA 23187-8795 Recommended Citation: Paxton, B.J., B.D. -

Wildlife Management Project Annual Job Report

PENNSYLVANIA GAME COMMISSION BUREAU OF WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT PROJECT ANNUAL JOB REPORT PROJECT CODE NO.: 06750 TITLE: Wildlife Diversity Research/Management JOB CODE NO.: 70004 TITLE: Colonial Nesting Bird Study PERIOD COVERED: 1 January 2012 to 31 December 2012 COOPERATING AGENCIES AND ORGANIZATIONS: Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources; East Stroudsburg University; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Federation of Sportsmen's Clubs in York; Powdermill Avian Research Center, Audubon Pennsylvania and associated chapters, Pennsylvania Society for Ornithology; Three Rivers Birding Club, Pittsburgh; York City Parks Department; Bird Refuge of York County, York. WORK LOCATION(S): Statewide PREPARED BY: Don Detwiler IV and Patricia Barber DATE: 30 January 2013 ABSTRACT This project inventories and monitors colonial waterbird populations in Pennsylvania, while reporting on conservation initiatives. Great egret, black-crowned night- heron, and yellow-crowned night-heron are endangered in Pennsylvania. Colonial wading birds are particularly vulnerable because their nests are clustered, putting a large part of the nesting population at risk from natural and human disturbances. The annual Wade Island survey identified 185 great egret, 67 black-crowned night-heron, and 188 double-crested cormorant nests. The 5-year comprehensive state wide survey was conducted confirming 77 active colonies of great blue heron in 33 counties. It is recommended that (1) additional 2013 effort supplement the comprehensive survey, visiting sites missed in 2012; (2) support continue for conservation measures at Wade Island, Ephrata, and Kiwanis Lake colonies; and (3) efforts continue to identify and conserve yellow-crown night-herons nesting in and near Harrisburg. OBJECTIVES 1. Inventory all colonial water bird populations by monitoring breeding sites, every 5 years. -

Water Withdrawal and Ninespine Stickleback

WATER WITHDRAWAL EFFECTS ON NINESPINE STICKLEBACK AND ALASKA BLACKFISH Lawrence L. Moulton MJM Research November 13, 2002 Introduction Information obtained in 2002 provided evidence that high levels of water withdrawal in lakes do not effect ninespine stickleback populations. Lakes along the ConocoPhillips Alaska ice road into eastern NPRA were previously sampled in 1999 and 2000 with gill nets and minnow traps (in 1999) to assess fish populations possibly present in the lakes. At that time, depth information was obtained to estimate water volume. The information obtained indicated that, in general, the lakes were shallow thaw lakes that did not provide habitat for whitefishes and arctic grayling. The sampling did not detect smaller species in some of the lakes and these lakes were treated as non-fish bearing lakes in subsequent permitting for winter water withdrawal. Gill nets have been used as the primary sampling method in lakes used to support exploration because previous experience in the Colville Delta demonstrated that fyke nets were not efficient in lakes with steep banks (Moulton 1997). Sites suitable for fyke net sampling are often scarce or non-existent in many lakes. Minnow traps were used to supplement gill net sampling in order to detect smaller species, such as ninespine stickleback and Alaska blackfish, but met with limited success. In 2002, lakes in the eastern NPRA region were re-sampled as part of the baseline studies for potential oil field development in the area. Lakes were sampled with fyke nets, which are quite effective in detecting smaller fish species that are not vulnerable to gillnet sampling.