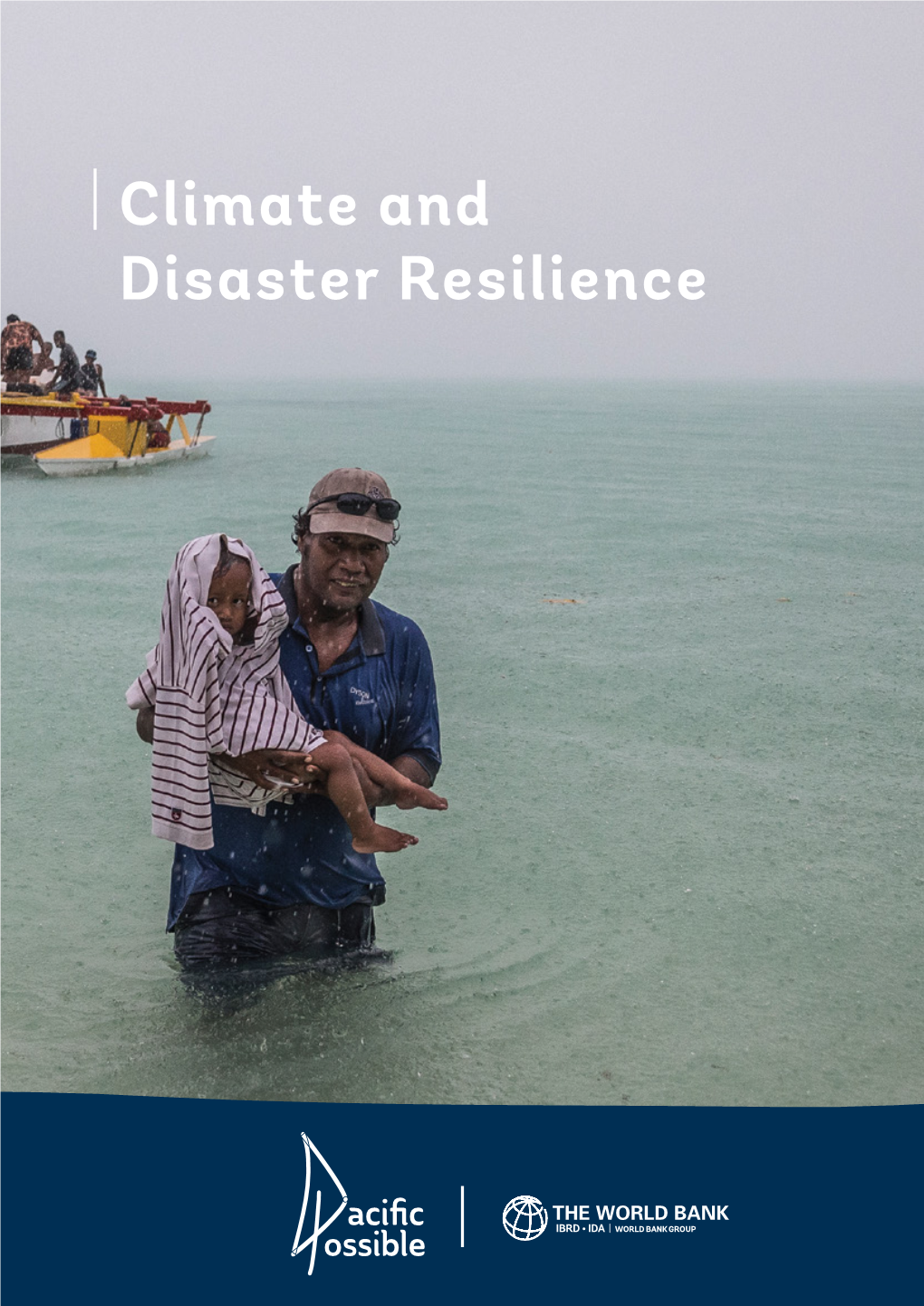

Climate and Disaster Resilience Pacific Island Countries Face Unique Development Challenges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pacific Study (Focusing on Fiji, Tonga and Vanuatu

1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 Hazard exposure 1.1. Pacific island countries (PICs) are vulnerable to a broad range of natural disasters stemming from hydro-meteorological (such as cyclones, droughts, landslide and floods) and geo-physical hazards (volcanic eruptions, earthquakes and tsunamis). In any given year, it is likely that Fiji, Tonga and Vanuatu are either hit by, or recovering from, a major natural disaster. 1.2. The impact of natural disasters is estimated by the Pacific Catastrophe Risk Assessment and Financing Initiative as equivalent to an annualized loss of 6.6% of GDP in Vanuatu, and 4.3% in Tonga. For Fiji, the average asset losses due to tropical cyclones and floods are estimated at more than 5%. 1.3. In 2014, Tropical Cyclone (TC) Ian caused damage equivalent to 11% to Tonga's GDP. It was followed in 2018 by damage close to 38% of GDP from TC Gita. In 2015, category five TC Pam displaced 25% of Vanuatu's population and provoked damage estimated at 64% of GDP. In Fiji, Tropical Cyclone Winston affected 62% of the population and wrought damage amounting to 31% of GDP, only some three and a half years after the passage of Tropical Cyclone Evan. 1.4. Vanuatu and Tonga rank number one and two in global indices of natural disaster risk. Seismic hazard is an ever-present danger for both, together with secondary risks arising from tsunamis and landslides. Some 240 earthquakes, ranging in magnitude between 3.3 and 7.1 on the Richter Scale, struck Vanuatu and its surrounding region in the first ten months of 2018. -

Shelter and Settlements Risk Profile NATURAL DISASTERS from 1980

Shelter and Settlements Risk Profile ShelterCluster.org Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter HISTORIC EVENTS (ReliefWeb) Dec 2012 1. Tropical Cyclone Evan KEY DEVELOPMENT INDICATORS Tropical Cyclone Evan (TC Evan) − a Category 4 cyclone, wind Full Name: Republic Of The Fiji Islands speeds of 210 km/h (130 mph), impacted Northern Vanua Population: 862,333 (UN, 2012) Levu and Western Viti Levu on 17 December 2012,is Annual Growth Rate: 0.5% considered one of the worst to ever hit Fiji in recent history. Capital: Suva Approximately 60% of the total population were affected in Population In Urban Areas: 52.90% the post-disaster period. The Northern division recorded the Area: 18,376 Sq Km(7,095 Sq.mile) highest percentage of affected population (52%) as a Major Languages: English, Fijian, Hindi proportion of their total population, followed by the Western Division (38%) and the Central and Eastern divisions (23%). Major Religions: Christianity, Hinduism, Islam March 2. Fiji: Floods Life Expectancy: (UN) 67 Years (M)/72 Years (W) 2012 Monetary Unit: 1 Fijian Dollar = 100 Cents Severe flooding in the areas of Ra, Tavua, Ba, Lautoka, Nadi, Main Exports: Sugar, Clothing, Gold, Processed Nadroga, Sigatoka, and Rewa in January 2012 The Fish, Timber Government of Fiji estimated that damage from the 2012 GNI Per Capita: US $3,720 (WB) 5,390 (FS) floods was at approximately F$71 million. This suggests that Human Development Index: 0.6881 Fiji experienced damage of F$146 million in 2012 alone. Rainfall In Capital (Mm): 3040 Jan 3. Fiji: Floods Temperature In Capital City ° C: 22.2/28.7 2012 Average Family Size: 5 March 4. -

VANUATU the Impact of Cyclone Pam

VANUATU The impact of Cyclone Pam Cyclone Pam – considered the worst natural disaster in the history of Vanuatu and the deadliest in the South Pacific since 2012 – made landfall on the 13th of March of 2015. The islands of Erromango, Tanna and Shepherd Islands which were directly on the path of the cyclone were among the most affected. Food Security Cluster Cyclone Pam impact maps & analysis Purpose of the assessment Purpose of the assessment The current report describes the impact of Acknowledgement Cyclone Pam throughout Vanuatu. Specifically, it reports on the cyclone’s impact WFP thanks the following for making and path to recovery in the areas of: available time and rapid field assessment reports on which this analysis is based: 1) Agriculture and livelihoods 2) Food needs NDMO 3) Housing UNDAC 4) Markets Women’s business and community 5) Health representatives of Port Vila. Peace Corps The report is designed to serve as a tool to Butterfly trust enable stakeholder/expert discussion and OCHA derive a common understanding on the ADF current situation. Food Security Cluster Samaritan’s Purse The report was compiled by: Siemon Hollema, Darryl Miller and Amy Chong (WFP) 1 Penama Cyclone Pam impact Sanma Cyclone Pam is the most powerful cyclone to ever hit the Southern Pacific. It formed near the Solomon Islands on the 6 March 2015 and traversed through Malampa several other island nations, including Solomon Islands, Kiribati and Tuvalu. On 13 March 2015, it strengthened to a Category 5 storm over the y-shaped chain of islands which make up Vanuatu. Vanuatu took multiple direct hits over 13 Mar 2015 the islands of Efate (where the capital Port Vila is 270km/h winds sustained situated), Erromango and Tanna Island. -

DISASTER RECOVERY Vanuatu Case Study

DISASTER RECOVERY Vanuatu case study http://www.realclimate.org/ Yachts in Port Vila harbour. Photo courtesy UNICEF Pacific A man escapes a dangerously high wave in Port Vila . Photo CARE Australia Homes damaged during Cyclone Pam. Photo AFP Homes flattened by TC Pam. Photo Dave Hunt-Pool/Getty Images Airforce personnel unload relief supplies. Photo Dave Hunt-Pool/Getty Images • Vanuatu considered to be the world’s most vulnerable country to natural hazards. (Due to a combination of Vanuatu’s exposure to both geophysical and hydro-meteorological hazards, and its limited financial and technical capacity to prepare for and respond to the associated risks). • Vanuatu located in the Pacific Ring of Fire and at the centre of the Pacific cyclone belt. (This results in a relatively high frequency of volcanic eruptions, cyclones, earthquakes, tsunamis, storm surges, coastal and river flooding, and landslides). • Vanuatu suffers from extreme events associated with climate variability, including sea-level and temperature extremes and droughts • Consequently, Vanuatu expected to incur, on average, US$48 million per year in losses due to earthquakes and tropical cyclones. (In the next 50 years, Vanuatu has a 50% chance of experiencing a loss exceeding US$330 million, and a 10% chance of experiencing a loss exceeding US$540 million). Source: Vanuatu Post-Disaster Needs Assessment March 2015 Disaster Risk profile of Vanuatu Between March 12 & 14, TC Pam struck Vanuatu as an extremely destructive Category 5 cyclone. Estimated wind speeds of 250km/h and wind gusts peaking at 320km/h. At approximately 11 p.m. local time on Friday March 13th, the centre of the cyclone passed east of Efate Island, which is home to the capital city of Port Vila, and then continued southward, passing just west of Erromango Island and Tanna Island. -

OCHA VUT Tcpam Sitrep6 20

Vanuatu: Tropical Cyclone Pam Situation Report No. 6 (as of 20 March 2015) This report is produced by the OCHA Regional Office for the Pacific (ROP) in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It covers the period from 19 to 20 March 2015. The next report will be issued on or around 21 March 2015. Highlights Around 166,000 people, more than half of Vanuatu’s population, have been affected by Tropical Cyclone Pam on 22 islands. Food stocks and water reserves are being exhausted and will not last more than a couple of weeks across the affected islands. The Government-led joint Initial Rapid Needs Assessments concluded on 20 March. Access to affected communities is still hindered in Emae Island and in the eastern part of Pentecote Island. An estimated 50-90 per cent of local dwellings have been damaged by gale-force winds. Fuel stocks are running low across the affected islands in Vanuatu while electricity is mostly unavailable and generators are essential. Around 65,000 people are in need of temporary emergency shelter. Schools postponed classes for two weeks with a start date of 30 March. There is an immediate need for temporary safe learning spaces for 50,000 to 70,000 children. 16 166,000 3,995 65,000 11,800 500 Confirmed fatalities People affected on People in 39 People in need of Households targeted Schools estimated to 22 islands evacuation centres temporary shelter for food distributions be damaged Source: Vanuatu National Disaster Management Office Situation Overview The Government-led joint Initial Rapid Needs Assessments concluded on 20 March confirmed the most urgent needs as water, food, shelter and health across the 22 affected islands in Vanuatu. -

The Impact of a Distant Cyclone on Atoll Islands

At the very edge of a storm: The impact of a distant cyclone on Atoll Islands Tauisi Taupo and Ilan Noy SEF WORKING PAPER 24/2016 WORKING PAPERS IN ECONOMICS AND FINANCE School of Economics and Finance | Victoria Business School | www.victoria.ac.nz/sef The Working Paper series is published by the School of Economics and Finance to provide staff and research students the opportunity to expose their research to a wider audience. The opinions and views expressed in these papers are not necessarily reflective of views held by the school. Comments and feedback from readers would be welcomed by the author(s). Further enquiries to: The Administrator School of Economics and Finance Victoria University of Wellington P O Box 600 Wellington 6140 New Zealand Phone: +64 4 463 5353 Email: [email protected] Working Paper 24/2016 ISSN 2230-259X (Print) ISSN 2230-2603 (Online) At the Very Edge of a Storm: The Impact of a Distant Cyclone on Atoll Islands Tauisi Taupo & Ilan Noy School of Economics & Finance Victoria University of Wellington October 2016 Abstract The intensity of cyclones in the Pacific is predicted to increase and sea levels are predicted to rise, so a small atoll nation like Tuvalu can serve as the ‘canary in the mine’ pointing to the new risks that are emerging because of climatic change. In Tuvalu, households are acutely vulnerable to storm surges caused by cyclones even if the cyclone itself passes very far away (in this case about a 1000km). Based on a survey we conducted in Tuvalu, we quantify the impacts of cyclone Pam (March 2015) on households, and the determinants of these impacts in terms of hazard, exposure, vulnerability and responsiveness. -

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO Diploma Thesis

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION Diploma thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Bc. Lukáš Opavský MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE Presentation Sentences in Wikipedia: FSP Analysis Diploma thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Bc. Lukáš Opavský Declaration I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. I agree with the placing of this thesis in the library of the Faculty of Education at the Masaryk University and with the access for academic purposes. Brno, 30th March 2018 …………………………………………. Bc. Lukáš Opavský Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. for his kind help and constant guidance throughout my work. Bc. Lukáš Opavský OPAVSKÝ, Lukáš. Presentation Sentences in Wikipedia: FSP Analysis; Diploma Thesis. Brno: Masaryk University, Faculty of Education, English Language and Literature Department, 2018. XX p. Supervisor: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Annotation The purpose of this thesis is an analysis of a corpus comprising of opening sentences of articles collected from the online encyclopaedia Wikipedia. Four different quality categories from Wikipedia were chosen, from the total amount of eight, to ensure gathering of a representative sample, for each category there are fifty sentences, the total amount of the sentences altogether is, therefore, two hundred. The sentences will be analysed according to the Firabsian theory of functional sentence perspective in order to discriminate differences both between the quality categories and also within the categories. -

Magnitudes of Nearshore Waves Generated by Tropical Cyclone Winston, the Strongest Landfalling Cyclone in South Pacific Records

ÔØ ÅÒÙ×Ö ÔØ Magnitudes of nearshore waves generated by Tropical Cyclone Winston, the strongest landfalling cyclone in South Pacific records. Unprecedented or unremarkable? James P. Terry, A.Y. Annie Lau PII: S0037-0738(17)30228-2 DOI: doi:10.1016/j.sedgeo.2017.10.009 Reference: SEDGEO 5252 To appear in: Sedimentary Geology Received date: 10 May 2017 Revised date: 11 October 2017 Accepted date: 13 October 2017 Please cite this article as: Terry, James P., Lau, A.Y. Annie, Magnitudes of nearshore waves generated by Tropical Cyclone Winston, the strongest landfalling cyclone in South Pacific records. Unprecedented or unremarkable?, Sedimentary Geology (2017), doi:10.1016/j.sedgeo.2017.10.009 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT Magnitudes of nearshore waves generated by Tropical Cyclone Winston, the strongest landfalling cyclone in South Pacific records. Unprecedented or unremarkable? James P. Terry1, A.Y. Annie Lau2 1 College of Natural and Health Sciences, Zayed University, Dubai, United Arab Emirates [email protected] 2 School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia Abstract We delimit nearshore storm waves generated by category-5 Tropical Cyclone Winston in February 2016 on the northern Fijian island of Taveuni. -

The Pacific Region ECHO FACTSHEET

The Pacific Region ECHO FACTSHEET shortage Facts & Figures EU emergency assistance in 2016: - €1 million in response to Tropical Cyclone Winston in Fiji - €2 million in response to drought in Papua New Guinea EU emergency assistance in 2015: - Over €1 260 000 for Papua New Guinea in response to El Niño- related drought and frost - €765 000 for humanitarian response to Cyclone Pam in Vanuatu In February 2016, large parts of Fiji were struck by Tropical Cyclone Winston, claiming 43 lives and EU emergency affecting over 350 000 people. © Navneet Narayan/IFRC assistance in 2014: - €1.5 million for sexual Key messages and gender-based violence in Papua New Guinea (2014-2015) The Pacific region is frequently hit by natural disasters such as cyclones, - Almost €173 000 in floods, droughts and earthquakes. Pacific countries rank among the response to floods in highest in the world in terms of numbers of casualties and people Solomon Islands affected. The European Commission provides humanitarian assistance to EU Disaster Risk Reduction funding in the region both in terms of disaster preparedness and emergency relief 2015-2016: when major disasters strike. - €2.5 million In response to the impact of the 2015-2016 El Niño system in several Pacific countries, the European Commission’s humanitarian aid department (ECHO) released funds for drought relief in the hardest-hit For further information country, Papua New Guinea. please contact ECHO’s regional office in Bangkok Following Tropical Cyclone Winston that swept across Fiji in late February Tel: +66 (0)2 305 2600 2016, the Commission made €1 million available to provide emergency assistance to the most vulnerable families. -

Tropical Cyclone Pam - Vanuatu 25 March 2015

Tropical Cyclone Pam - Vanuatu 25 March 2015 PEOPLE AFFECTED 160,000+ People affected HEALTH SECTOR Many health facilities are damaged, including the country’s main tertiary hospital in Port Vila and the main hospital on the island of Tanna. Assessment of other facilities is ongoing. Major health risks Acute diarrhea due to lack of safe drinking water and poor sanitation Late treatment of infected wounds and fractures Ongoing Measles outbreak Current Situation Communicable disease outbreaks, including dengue and leptospirosis Tropical Cyclone Pam has been described as the strongest cyclone to hit the Pacific Islands in more than a decade. The severe storm battered Interruption of treatment of chronic Vanuatu with winds of over 250 km/h and 1-metre storm surges. Kiribati, conditions such as hypertension, the Solomon Islands and Tuvalu were also impacted. diabetes, mental disorders Poor access to perinatal care The total number of fatalities recorded to date is 11. The number of injured FUNDING REQUIREMENTS is increasing daily as patients, many with infected and untreated wounds, are beginning to access health facilities as transportation routes re-open. US $3 million requested for WHO’s However, health service delivery has been severely disrupted, mainly due initial response to the crisis to the damage to health facilities; the interruption of transportation, $0 received 100% funding gap communications, water and energy supplies is also having an impact. US $4.9 million required by More than 4,000 people have been displaced from their homes. While some are gradually returning home, many people remain displaced. The Health Cluster cyclone has affected more than 166,000 people in Vanuatu, representing CONTACT more than 70% of the country’s total population of the country, and has Country Office: caused widespread and severe damage throughout the country, Adam Craig, Information and particularly in the central and southern regions which experienced the Communications Officer brunt of the storm. -

Cyclone PAM Post Inundation Assessment Survey Using UAV

Cyclone PAM Post Inundation Assessment Survey using UAV Herve Damlamian, Cyprien Bosserelle, Amrit Raj, Zulfikar Begg, Jens Kruger. [email protected] Tropical Cyclone PAM Preliminary Wave model of Cyclone Pam Tuvalu: • AU$ ~14M • 25% of TV 2013 GDP • 41% population affected • 90% damage on crops in 3 Islands, 30% damage on crops in 4 Islands Vanuatu: • 16 death • 65,000 people displaced • >50% population affected (166,000) • 17,000 buildings affected • AU$ ~619M – Damage and Loss • 64.1% of GDP • Livelihood of more than 80% of rural population affected. Other countries affected: New Caledonia, Solomon Island, Kiribati, New-Zealand. Post Disaster Assessment Survey • Rapid Damage Assessment – Collect high resolution images to assess building damage. • Extreme Wave Inundation and Impact Assessment – Collect Inundation data from an extreme wave event. – Assess use of UAV for Post disaster inundation impact assessment. Post PAM Inundation Assessment 3D Shoreline Mapping Methodology • Generate high resolution Topography of coastal areas: – Setting up temporary tide gauge. – Setting up Bench Marks in Targeted areas. – Using RTK GPS System to Establish GCPs. – UAV mapping with 90% overlap • Compare with LIDAR data (2012) Preliminary Wave model of Cyclone Pam, Efate Point Cloud: Takara Village, NE Efate Inundation Extent and Run-up Debris line 240m Inundation extent 7m run-up (Above TGZ) Debris line 3D Shoreline Change • ORTHOPHOTO Prior Cyclone • DTM PAM LIDAR DATA (2012) After Cyclone PAM UAV DATA (2015) Example: Map of Change Takara Village, -

1 at the Very Edge of a Storm: the Impact of a Distant Cyclone on Atoll Islands Tauisi Taupo & Ilan Noy School of Economics

At the Very Edge of a Storm: The Impact of a Distant Cyclone on Atoll Islands Tauisi Taupo & Ilan Noy School of Economics & Finance Victoria University of Wellington Abstract The intensity of cyclones in the Pacific is predicted to increase and sea levels are predicted to rise, so an atoll nation like Tuvalu can serve as the ‘canary in the mine’ pointing to the new risks that are emerging because of climatic change. Based on a household survey we conducted in Tuvalu, we quantify the impacts of Tropical Cyclone Pam (March 2015) on households, and the determinants of these impacts in terms of hazard, exposure, vulnerability and responsiveness. Households experienced significant damage due to the storm surge caused by the cyclone, even if the cyclone itself passed very far away (about a 1000km). This risk of distant cyclones has been overlooked in the literature, and ignoring it leads to significant under-estimation of the disaster risk facing low-lying atoll islands. Lastly, we constructed hypothetical policy scenarios, and calculated the estimated loss and damage they would have been associated with – a first step in building careful assessments of the feasibility of various disaster risk reduction policies. Keywords: vulnerability, exposure, hazard, responsiveness, and Tuvalu We are indebted to all interviewers for carrying out the field work in Tuvalu, and the Tuvalu Central Statistics Office for their valuable inputs and immense support. Taupo also acknowledges the financial support of the NZAID. 1 1 Introduction Among the Small Island Developing States (SIDS) in the Pacific, Tuvalu consists of nine low- lying atoll islands spread over a large expanse of ocean.