Based on the Crown Diameter1d.B.H. Relationship of Open-Grown Sugar Maples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hawaii's Sugar Plantations Reading Folder

Hawaii's Sugar Plantations Reading Folder Pictures from: http://www.kauaiplantationrailway.com/agplantations.htm Women’s Work Clothing fuller skirts that seemed to be more suitable for field work. The Hawaiian women had learned to sew their gathered skirts from the The issei women, like the issei men, at first took whatever they had missionary women. It was easier and faster to use thirty-six-inch brought with them from their homeland and put together makeshift American cotton fabric, which cost ten cents a yard. The women work outfits. Later they also adopted some of the types of clothing favored prints, usually in black and white, often the tiny floral or worn by other ethnic groups. As the women from different ethnic geometric designs. groups and cultures came into contact, a gradual exchange of ideas began. Hats The issei women retained some of their traditional ideas and threw The boater hat was a stiff hat of braided straw. Underneath the away others; they adopted useful ideas from other ethnic groups; boater hat, or in some cases, over it, the women wore a triangular- often they blended the old and the new. Through this assimilation shaped kerchief made of muslin or bleached rice bag. The kerchief of new ideas into their traditional costume, the issei women created covered the hair, the ears, and most of the face. a unique fashion: the kasuri jacket, the dirndl skirt, the black cummerbund-like sash and the straw hat. Men’s Work Clothing In the early years of the Japanese immigration to Hawaii, the men Jackets started to work in the sugarcane fields wearing their cotton kimono, The first kind of clothing worn by issei women for field work was the momohiki (fitted pants), and shirts with long, narrow sleeves. -

Utilization of Baggase Waste Based Materials As Improvement for Thermal Insulation of Cement Brick

MATEC Web of Conferences 103, 01019 (2017) DOI: 10.1051/ matecconf/201710301019 ISCEE 2016 Utilization of Baggase Waste Based Materials as Improvement for Thermal Insulation of Cement Brick Eeydzah Aminudin1,*, Nur Hafizah A. Khalid 1, Nor Ain Azman2, Khairuniza Bakri2, 3 1 3 Mohd Fadhil Md Din , Rozana Zakaria , and Nur Azmira Zainuddin 1Department of Structures and Materials, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, 81310, Johor 2Department of Building and Construction, Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia, Batu Pahat 3Department of Environmental Engineering, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, 81310, Johor Abstract. Building materials having low thermal load and low thermal conductivity will provide thermal comforts to the occupants in building. In an effort to reduce the use of high energy and waste products from the agricultural industry, sugarcane bagasse and banana bagasse has been utilize as an additive in the manufacture of cement brick. The aim of this study is to investigate the insulation and mechanical properties of brick that has been mixed with bagasse and its effectiveness as thermal insulation using heat flow meter. Waste bagasse is being treated using sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and is characterized using SEM and XRF. The samples produced with two different dimensions of 50 mm x 50 mm x 50 mm and 215mm x 102.5mm x 65mm for thermal conductivity test. Next, the sample varies from 0% (control sample), 2%, 4%, 6%, 8% and 10% in order to determine the best mix proportion. The compressive strength is being tested for 7, 14 and 28 days of water curing. Results showed that banana bagasse has lower thermal conductivity compared to sugarcane bagasse used, with compressive strength of 15.6MPa with thermal conductivity 0.6W/m.K. -

Welcome to the Walk of Change Nature Trail

Welcome to the Walk of Change 3. Monarch butterflies former land clearing for farming. The size of the 6. Is this The End? Monarch butterflies have one of the most stones may reveal whether the adjacent land was As you walked to this stop you may have noticed Nature Trail unusual and extreme life cycles of North used for crops or pasture. Stone piles or walls with a change in light and temperature. You just walked American butterflies. Adults migrate north, large rocks usually suggest the adjacent land was through a climax community. In this case, it is a Here at Knight Island State Park, the arriving in the northeast early in the growing a mowed field or a pasture in which only the large patch of mature forest. This does not mean the end landscape has been affected by many physical season. After mating, a female lays her eggs rocks needed to be removed. Small stones need to of change, though, or static condition in the forest. environmental and cultural factors over the on Common Milkweed, like you can see here. be removed from cultivated plots annually. This New growth slows as the forest canopy becomes geologic timescale. These include weather pile of small stones reveals that the surrounding enclosed with fewer, larger trees that are more extremes, glaciers, human habitation and area was used for crops. The crops grown on spaced out. At this state in a forest’s evolution, livestock grazing. Enjoy a walk along the Knight Island were beans, com and peas. change is brought by natural events such as storms trail system, and keep watch for signs of Common milkweed bringing wind and ice, or from cultural means like these changes; you might even witness some logging. -

1 Sap Collection from Small-Diameter Trees Timothy

Sap Collection from Small-Diameter Trees Timothy Perkins and Abby van den Berg University of Vermont Proctor Maple Research Center Underhill Center, VT 05490 [email protected], [email protected] For several years, we conducted research on the collection of sap from small-diameter maple trees. This document outlines the basic concepts, techniques, and applications of this type of sap collection.† The fundamental premise of this type of sap collection is that sap is collected from the cut surface of small-diameter trees rather than through a taphole drilled in a larger stem. Initial cuts on intact trees are made approximately 5-6' above ground level at a height reasonably convenient for running tubing (Figure 1). The cut is most easily accomplished using a sharp bow-saw. Sap is collected from the cut surface of the stem using a cap-type fitting connected to a tubing system with vacuum (Figure 1). Vacuum is necessary; otherwise sap flows will be negligible. The cut to the stem needs to be as clean as possible to facilitate optimum sapflow, and care should be taken not to damage remaining bark tissues during the cutting process. The area of the stem where the cap is placed should be as smooth and free from defects as possible to facilitate a vacuum-tight fit. A clear zone of smooth bark approximately 3-4" long should extend below the cut to allow a good seal with the sap collection cap. Good sanitation practices should be used to avoid contamination of the cut stem. The cut top of the tree could be put aside and used later for mulch or fuel. -

Productivity of Honeybees in Oil Palm Integrated System in Niger- Delta of Nigeria F.N

The Journal of Agriculture and Environment Vol:12, Jun.2011 Technical Paper PRODUCTIVITY OF HONEYBEES IN OIL PALM INTEGRATED SYSTEM IN NIGER- DELTA OF NIGERIA F.N. Emuh*1 and A.U.Ofuoku2 ABSTRACT For two consecutive years in Abbi, Delta State of Niger-Delta of Nigeria one, two and three beehives were integrated in oil palm plantation to determine optimum productivity of the oil-palm honey bee farming system. The fresh fruit bunch (economic yield) of the oil palm was statistically similar at 0, 1, 2 and 3 bee hive(s) per hectare. The honey yield were statistically similar for each bee hive/kg/ha while the total honey yield/production was significantly higher in the order of three > two > one bee hive/ha. Result obtained in this study indicates that productivity of oil palm plantation + three Beehives/ha which produced more honey is recommended. Keywords: African honeybee, economic yield. honey-yield, oil palm INTRODUCTION Honey is sucked nectar, saccharine exudation of plants, modified by honeybees and stored in beehive (s). It is rich in albumen, amino acid, ascorbic acid, copper, folic acid, fructose, glucose, iron, maltose, nicotinic acid, nitrogen, sodium, sucrose, vitamins B1, B2, B5, C4, D and K (Ayansola, 2003). It is used as tonic food, promotes growth, maintains acid - base balance of the body, has antibiotic properties and used for spiritual and mystical purposes (Holy Bible, 2000; Ayansola, 2003; Ayodele and Onyekuru, 2005) Most honey is sourced from honeybees in the wild. Honeybees and tree crops especially flowering plants has a symbolic relationship. The flowers provide nectar, a carbohydrate food for the bees, which is a raw material for honey production, while the bees in turn pollinate the flowers which enable the plant to reproduce. -

3 Bagasse Caribbean Art and the Debris of the Sugar Plantation

3 Bagasse Caribbean Art and the Debris of the Sugar Plantation Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert The recent emergence of bagasse—the fibrous mass left after sugarcane is crushed—as an important source of biofuel may seem to those who have experienced the realities of plantation life like the ultimate cosmic irony. Its newly assessed value—one producer of bagasse pellets argues that “sym- bol of what once was waste, now could be farming gold” (“ Harvesting” 2014)—promises to increase sugar producers’ profits while pushing into deeper oblivion the plight of the workers worldwide who continue to pro- duce sugar cane in deplorable conditions and ruined environments. Its newly acquired status as a “renewable” and carbon-neutral source of energy also obscures the damage that cane production continues to inflict on the land and the workers that produce it. The concomitant deforestation, soil erosion and use of poisonous chemical fertilizers and pesticides on land and water continue to degrade the environment of those fated to live and work amid its waste. It obscures, moreover, the role of sugarcane cultivation as the most salient form of power and environmental violence through which empires manifested their hegemony over colonized territories throughout the Caribbean and beyond.1 In the discussion that follows, I explore the legacy of the environmental violence of the sugar plantation through the analysis of the work of a group of contemporary Caribbean artists whose focus is the ruins and debris of the plantation and who often use bagasse as either artistic material or symbol of colonial ruination. I argue—through the analysis of recent work by Ate- lier Morales (Cuba), Hervé Beuze (Martinique), María Magdalena Campos- Pons (Cuba), and Charles Campbell (Jamaica)—that artistic representation in the Caribbean addresses the landscape of the plantation as inseparable from the history of colonialism and empire in the region. -

Blackbirding Cases

SLAVING IN AUSTRALIAN COURTS: BLACKBIRDING CASES Home About JSPL Submission Information Current Issue Journal of Search South Pacific Law Volume 4 2000 2008 2007 SLAVING IN AUSTRALIAN COURTS: BLACKBIRDING CASES, 1869-1871 2006 2005 By Reid Mortensen[*] 2004 1. INTRODUCTION 2003 2002 This article examines major prosecutions in New South Wales and 2001 Queensland for blackbirding practices in Melanesian waters, and early regulation under the Imperial Kidnapping Act that was meant to 2000 correct problems those prosecutions raised. It considers how legal 1999 argument and adjudication appropriated the political debate on the question whether the trade in Melanesian labour to Queensland and 1998 Fiji amounted to slaving, and whether references to slaving in 1997 Australian courts only compounded the difficulties of deterring recruiting abuses in Melanesia. It is suggested that, even though the Imperial Government conceived of the Kidnapping Act as a measure to deal with slaving, its success in Australian courts depended on its avoiding any reference to the idea of slavery in the legislation itself. This is developed in three parts. Part 1 provides the social context, introducing the trade in Melanesian labour for work in Queensland. Part 2 explores the prosecutions brought under the slave trade legislation and at common law against labour recruiters, especially those arising from incidents involving the Daphne and the Jason. It attempts to uncover the way that lawyers in these cases used arguments from the broader political debate as to whether the trade amounted to slaving. Part 3 concludes with an account of the relatively more effective regulation brought by the Kidnapping Act, with tentative suggestions as to how the arguments about slaving in Australian courts influenced the form that regulation under the Act had to take. -

361 BLACKBIRDING a Brief History of the South Sea Islands

361 BLACKBIRDING A brief history of the South Sea Islands Labour Traffic and the vessels engaged in it. (Paper by E. V. STEVENS read at the meeting of the Historical Society of Queensland, Inc., 23rd March 1950) Old Wine in New Bottles! ... An inadequate tri bute to those ruffians whose salty tales, told in Mar tin's Ship Chandlery, spiced with the odour of tarred hemp, canvas and cordage, stirred the imagination of a small boy sixty years ago: specially to John Poro from whom came many a welcome sixpence for some small act of service rendered. To me John Poro was a nice old gentleman; I still think so despite the later knowledge, that he was indicted, though discharged for manslaughter. This paper consists of two sections, one dealing with the subject from a different angle, I hope, from those previously presented. No stress has been laid upon the ethical, economic, or legislative implications. The object sought has been to give a general and ob jective view of this colourful period. The second sec tion of this paper contains a brief record of some 130 vessels engaged in recruiting South Sea Island labour since its beginning in 1863 to its conclusion in 1902; this as a record of vessels, masters, incidents, and fates is of no immediate interest but, documented reasonably well, may prove of service to some more ex haustive future survey. The task attempted would have been well nigh im possible had it not been for assistance rendered by our fellow-member, Mr. J. H. C McClurg, and Capt. -

Belle Chasse Plantation Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana

Belle Chasse Plantation Plaquemines Parish, FEMA’s Historic Preservation Staff and Coastal Louisiana Belle Chasse in circa 1916 Environments, Inc. created this pamphlet in par- tial fulfillment of the Standard Treatment Measures The French first settled Plaquemines Parish in the In 1852, Benjamin sold his interest in Belle Chasse to (STMs) for the Belle Chasse Water Treatment Plant 1720s. They grew indigo on Mississippi River planta- the Packwoods, who passed the plantation to Virginian Expansion and Main Street Drainage Improvement tions located above and below Belle Chasse. French James E. Zunts in 1860. Zunts sold Belle Chasse to projects. These projects included ground disturbing families settled between these plantations, but most Pennsylvanian William Stackhouse in 1865, but the land activities that affected a historic property in a way abandoned their farms in the 1730s. In the 1740s, the reverted back to Zunts in 1874. By 1879, their planta- that directly affected the characteristics that made the French built Forts St. Leon and Ste. Marie at English tion had grown to 3.25 miles of river frontage. Zunts’ property eligible for the National Register of Historic Turn because of its strategic location. heirs passed Belle Chasse to Virginian Joseph Kearney Places (NRHP) and per 36 CFR 800.6 constituted an in the early 1890s. Kearney built a second sugarhouse adverse effect. Therefore, in 2016, FEMA determined Free people of color, some likely former slaves, acquired on the plantation and a railroad spur to the New Or- a finding of Historic Properties Adversely Affected most of the river frontage in the Belle Chasse area be- leans, Fort Jackson and Grand Isle Railroad. -

Cuban Sugar Industry

Cuban Sugar Industry Cuban Sugar Industry Transnational Networks and Engineering Migrants in Mid-Nineteenth Century Cuba Jonathan Curry-Machado CUBAN SUGAR INDUSTRY Copyright © Jonathan Curry-Machado, 2011. Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2011 978-0-230-11139-4 All rights reserved. First published in 2011 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN® in the United States—a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Where this book is distributed in the UK, Europe and the rest of the world, this is by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN 978-1-349-29372-8 ISBN 978-0-230-11888-1 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230118881 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Curry-Machado, Jonathan. Cuban sugar industry : transnational networks and engineering migrants in mid-nineteenth century Cuba / Jonathan Curry-Machado. p. cm. 1. Sugar trade—Cuba—History. 2. Engineers—Cuba—History. 3. Immigrants—Cuba—History. I. Title. HD9114.C89C87 2011 338.1Ј7361097291—dc22 2010043766 A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library. Design by Newgen Imaging Systems (P) Ltd., Chennai, India. First edition: May 2011 In memory of those who remain -

Turpentine History Loop: Clubhouse Along the Bikepath to Suzie Court and Return

Turpentine History Loop: Clubhouse along the bikepath to Suzie Court and Return 11 1 2 10 Turpentine was a major industry for collection of Naval 3 Stores through to the mid 20th century. A 4 7 gentle walking loop (1.5 miles) enables 5 8 one to see its history 9 on SGI and within 6 the Plantation Prepared by Jim Mott Turpentine is a natural liquid obtained by the distillation of pine resin obtained from live pine trees. The resin is harvested by cutting the tree bark (so injuring the tree) and collecting the sticky resin that the tree secretes in order to try to heal and protect itself. At the base of the boiling turpentine still, the separated residual liquid (rosin) is then poured off to harden. The rosin can be reheated to make it soft for use (as caulking for example). Turpentine was used medicinally since ancient times, mostly topical but sometimes as internal medicine. it was widely used for abrasions and wounds, and when mixed with animal fat it has been used as a chest rub, or inhaler for nasal and throat ailments. 19th and early 20th century chest rubs, contained turpentine in their formulations. Taken internally (sugar, molasses or honey used to mask the taste) turpentine was injested as treatment for intestinal parasites owing to its alleged antiseptic and diuretic properties. Brush was carefully kept clear from around each tree, owing to fire risk and to watch out for poisonous snakes. The sloped grooves (cat-faces) then cut into the pine bark gave two products, pine resin that slowly dripped into a ‘Herty’ cup and a hardened resin ‘scape’ that solidified on face; both products were scooped into pails, then barrels, and transported away to a large still for boiling and refining. -

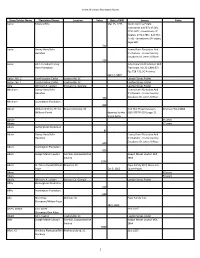

Index of Known Plantation Slaves Slave/Soldier Name Plantation

Index of Known Plantation Slaves Slave/Soldier Name Plantation/Owner Location Value Date of Will Source Notes Aaron Edmond Ellis Mar 15, 1775 South Carolina Estate Inventories and Bills of Sale, 1732-1872 - Inventories Of Estates, 1772-1785 › & (1772- 1776) › Inventories Of Estates; page 560 500 Aaron Honey Horn/John Honey Horn Plantation And Hanahan It's Owners - A Low Country Database; Dr James M Rose 500 Aaron John Hanahan/Honey John Hanahan Charleston Will Horn Plantation Transcript, Vol 29 (1800-07) Pgs 728-731, SC Archives Sep 17, 1804 Aaron, NO. 2 Sarah Lawton Clarke Lawtonville, SC Lawton Slaves Folder Aaron. No. 1 Sarah Lawton Clarke Lawtonville, SC Lawton Slaves Folder Able Winborn A. Lawton Screven Co. Georgia Lawton Slaves Folder Abraham Honey Horn/John Honey Horn Plantation And Hanahan It's Owners - A Low Country 300 Database; Dr James M Rose Abraham Leamington Plantation 800 Abram William W Elliot, Prince Beaufort County, SC Civil War Property Losses 32 years; 9/11/1862 Williams Parish deserted to the (929.375799 CIV) page 12 Union Army Abram 35 years Abram 17 years Adam Buchingham Plantation 80 Adam Honey Horn/John Honey Horn Plantation And Hanahan It's Owners - A Low Country Database; Dr James M Rose 600 Adam Leamington Plantation 800 Adam Joseph Maner Lawton Grimkie, Coosawhatchie Joseph Maner Lawton Will, Swamp 1864 2300 Adam St. Peters Parish/William Beaufort, SC Pope Family File ( this is not Pope Oct 3, 1862 Squire Pope) Adam 30 years Adam 50 years Adella Winborn A. Lawton Screven Co. Georgia Lawton Slaves Folder Affey Buchingham Plantation 600 Affey Leamington Plantation 600 Affy River May Bluffton, SC Pope Family files Plantation/Wiliam Pope 1827-1839 Aiken, Joseph Gov.