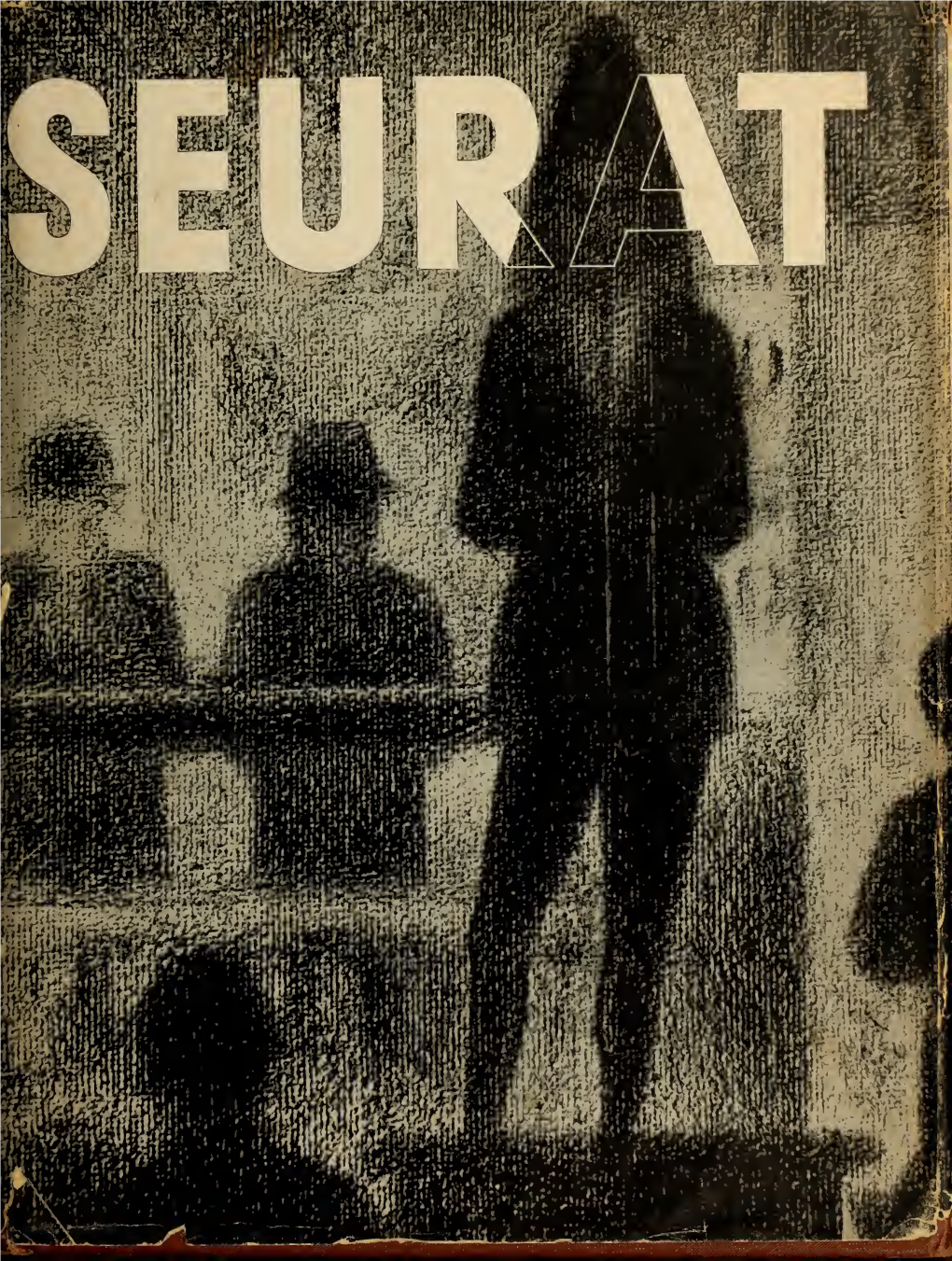

Georges Seurat by John Rewald

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heather Buckner Vitaglione Mlitt Thesis

P. SIGNAC'S “D'EUGÈNE DELACROIX AU NÉO-IMPRESSIONISME” : A TRANSLATION AND COMMENTARY Heather Buckner Vitaglione A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of MLitt at the University of St Andrews 1985 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/13241 This item is protected by original copyright P.Signac's "D'Bugtne Delacroix au n6o-impressionnisme ": a translation and commentary. M.Litt Dissertation University or St Andrews Department or Art History 1985 Heather Buckner Vitaglione I, Heather Buckner Vitaglione, hereby declare that this dissertation has been composed solely by myself and that it has not been accepted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a candidate for the degree of M.Litt. as of October 1983. Access to this dissertation in the University Library shall be governed by a~y regulations approved by that body. It t certify that the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations have been fulfilled. TABLE---.---- OF CONTENTS._-- PREFACE. • • i GLOSSARY • • 1 COLOUR CHART. • • 3 INTRODUCTION • • • • 5 Footnotes to Introduction • • 57 TRANSLATION of Paul Signac's D'Eug~ne Delac roix au n~o-impressionnisme • T1 Chapter 1 DOCUMENTS • • • • • T4 Chapter 2 THE INFLUBNCB OF----- DELACROIX • • • • • T26 Chapter 3 CONTRIBUTION OF THE IMPRESSIONISTS • T45 Chapter 4 CONTRIBUTION OF THB NEO-IMPRBSSIONISTS • T55 Chapter 5 THB DIVIDED TOUCH • • T68 Chapter 6 SUMMARY OF THE THRBE CONTRIBUTIONS • T80 Chapter 7 EVIDENCE • . • • • • • T82 Chapter 8 THE EDUCATION OF THB BYE • • • • • 'I94 FOOTNOTES TO TRANSLATION • • • • T108 BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • • • T151 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Plate 1. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/04/2021 08:07:20AM This Is an Open Access Chapter Distributed Under the Terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR HISTORY, CULTURE AND MODERNITY www.history-culture-modernity.org Published by: Uopen Journals Copyright: © The Author(s). Content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence eISSN: 2213-0624 L’Art pour l’Art or L’Art pour Tous? The Tension Between Artistic Autonomy and Social Engagement in Les Temps Nouveaux, 1896–1903 Laura Prins HCM 4 (1): 92–126 DOI: 10.18352/hcm.505 Abstract Between 1896 and 1903, Jean Grave, editor of the anarchist journal Les Temps Nouveaux, published an artistic album of original prints, with the collaboration of (avant-garde) artists and illustrators. While anar- chist theorists, including Grave, summoned artists to create social art, which had to be didactic and accessible to the working classes, artists wished to emphasize their autonomous position instead. Even though Grave requested ‘absolutely artistic’ prints in the case of this album, artists had difficulties with creating something for him, trying to com- bine their social engagement with their artistic autonomy. The artistic album appears to have become a compromise of the debate between the anarchist theorists and artists with anarchist sympathies. Keywords: anarchism, France, Neo-Impressionism, nineteenth century, original print Introduction While the Neo-Impressionist painter Paul Signac (1863–1935) was preparing for a lecture in 1902, he wrote, ‘Justice in sociology, har- mony in art: same thing’.1 Although Signac never officially published the lecture, his words have frequently been cited by scholars since the 1960s, who claim that they illustrate the widespread modern idea that any revolutionary avant-garde artist automatically was revolutionary in 92 HCM 2016, VOL. -

ONE HUNDRED DRAWINGS and WATERCOLOURS Dating from the 16Th Century to the 21St Century

O N E H U N D R E D ONE HUNDRED D R A W I N DRAWINGS G S & W A AND T E R C O L O WATERCOLOURS U R S S T E P H E N O N G P I N G U Y P E P P I A T T Stephen Ongpin Fine Art Ltd. Guy Peppiatt Fine Art Ltd. 2 0 1 7 Riverwide House - 2 0 6 Mason’s Yard 1 Duke Street, St James’s 8 London SW1Y 6BU 100 drawings PART 1.qxp 13/11/2017 09:10 Page 1 GUY PEPPIATT FINE ART STEPHEN ONGPIN FINE ART ONE HUNDRED DRAWINGS AND WATERCOLOURS dating from the 16th Century to the 21st Century WINTER CATALOGUE 2017–2018 to be exhibited at Riverwide House 6 Mason’s Yard Duke Street, St. James’s London SW1Y 6BU Stephen Ongpin Fine Art Guy Peppiatt Fine Art Tel.+44 (0) 20 7930 8813 Tel.+44 (0) 20 7930 3839 or + 44 (0)7710 328 627 or +44 (0)7956 968 284 [email protected] [email protected] www.stephenongpin.com www.peppiattfineart.co.uk 1 100 drawings PART 1.qxp 14/11/2017 11:23 Page 2 We are delighted to present our tenth annual Winter catalogue of One Hundred Drawings and Watercolours, which includes a wide range of British and European drawings and watercolours, placed more or less in chronological order, ranging in date from the 16th century to nearly the present day. Although the areas of Old Master drawings, early British drawings and watercolours, 19th Century and Modern drawings have long been regarded as disparate fields, part of the purpose of this annual catalogue is to blur the distinction between these collecting areas. -

Master Artist of Art Nouveau

Mucha MASTER ARTIST OF ART NOUVEAU October 14 - Novemeber 20, 2016 The Florida State University Museum of Fine Arts Design: Stephanie Antonijuan For tour information, contact Viki D. Thompson Wylder at (850) 645-4681 and [email protected]. All images and articles in this Teachers' Packet are for one-time educational use only. Table of Contents Letter to the Educator ................................................................................ 4 Common Core Standards .......................................................................... 5 Alphonse Mucha Biography ...................................................................... 6 Artsits and Movements that Inspired Alphonse Mucha ............................. 8 What is Art Nouveau? ................................................................................ 10 The Work of Alphonse Mucha ................................................................... 12 Works and Movements Inspired by Alphonse Mucha ...............................14 Lesson Plans .......................................................................................... Draw Your Own Art Nouveau Tattoo Design .................................... 16 No-Fire Art Nouveau Tiles ............................................................... 17 Art Nouveau and Advertising ........................................................... 18 Glossary .................................................................................................... 19 Bibliography ............................................................................................. -

Daxer & Marschall 2015 XXII

Daxer & Marschall 2015 & Daxer Barer Strasse 44 - D-80799 Munich - Germany Tel. +49 89 28 06 40 - Fax +49 89 28 17 57 - Mobile +49 172 890 86 40 [email protected] - www.daxermarschall.com XXII _Daxer_2015_softcover.indd 1-5 11/02/15 09:08 Paintings and Oil Sketches _Daxer_2015_bw.indd 1 10/02/15 14:04 2 _Daxer_2015_bw.indd 2 10/02/15 14:04 Paintings and Oil Sketches, 1600 - 1920 Recent Acquisitions Catalogue XXII, 2015 Barer Strasse 44 I 80799 Munich I Germany Tel. +49 89 28 06 40 I Fax +49 89 28 17 57 I Mob. +49 172 890 86 40 [email protected] I www.daxermarschall.com _Daxer_2015_bw.indd 3 10/02/15 14:04 _Daxer_2015_bw.indd 4 10/02/15 14:04 This catalogue, Paintings and Oil Sketches, Unser diesjähriger Katalog Paintings and Oil Sketches erreicht Sie appears in good time for TEFAF, ‘The pünktlich zur TEFAF, The European Fine Art Fair in Maastricht, European Fine Art Fair’ in Maastricht. TEFAF 12. - 22. März 2015, dem Kunstmarktereignis des Jahres. is the international art-market high point of the year. It runs from 12-22 March 2015. Das diesjährige Angebot ist breit gefächert, mit Werken aus dem 17. bis in das frühe 20. Jahrhundert. Der Katalog führt Ihnen The selection of artworks described in this einen Teil unserer Aktivitäten, quasi in einem repräsentativen catalogue is wide-ranging. It showcases many Querschnitt, vor Augen. Wir freuen uns deshalb auf alle Kunst- different schools and periods, and spans a freunde, die neugierig auf mehr sind, und uns im Internet oder lengthy period from the seventeenth century noch besser in der Galerie besuchen – bequem gelegen zwischen to the early years of the twentieth century. -

Download Lot Listing

IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART Wednesday, May 10, 2017 NEW YORK IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART EUROPEAN & AMERICAN ART POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART AUCTION Wednesday, May 10, 2017 at 11am EXHIBITION Saturday, May 6, 10am – 5pm Sunday, May 7, Noon – 5pm Monday, May 8, 10am – 6pm Tuesday, May 9, 9am – Noon LOCATION Doyle New York 175 East 87th Street New York City 212-427-2730 www.Doyle.com Catalogue: $40 INCLUDING PROPERTY CONTENTS FROM THE ESTATES OF IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART 1-118 Elsie Adler European 1-66 The Eileen & Herbert C. Bernard Collection American 67-118 Charles Austin Buck Roberta K. Cohn & Richard A. Cohn, Ltd. POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART 119-235 A Connecticut Collector Post-War 119-199 Claudia Cosla, New York Contemporary 200-235 Ronnie Cutrone EUROPEAN ART Mildred and Jack Feinblatt Glossary I Dr. Paul Hershenson Conditions of Sale II Myrtle Barnes Jones Terms of Guarantee IV Mary Kettaneh Information on Sales & Use Tax V The Collection of Willa Kim and William Pène du Bois Buying at Doyle VI Carol Mercer Selling at Doyle VIII A New Jersey Estate Auction Schedule IX A New York and Connecticut Estate Company Directory X A New York Estate Absentee Bid Form XII Miriam and Howard Rand, Beverly Hills, California Dorothy Wassyng INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM A Private Beverly Hills Collector The Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Raymond J. Horowitz sold for the benefit of the Bard Graduate Center A New England Collection A New York Collector The Jessye Norman ‘White Gates’ Collection A Pennsylvania Collection A Private -

Theo Van Gogh to Vincent Van Gogh. Paris, Saturday, 16 November 1889

Theo van Gogh to Vincent van Gogh. Paris, Saturday, 16 November 1889. Saturday, 16 November 1889 Metadata Source status: Original manuscript Location: Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum, inv. nos. b747 a-b V/1962 Date: Letter headed: Paris le 16 Nov: 1889. Additional: Letter 817 from Gauguin was enclosed. Original [1r:1] Paris le 16 Nov: 1889 Mon cher Vincent, Je tenvois sous ce pli une lettre que Gauguin ma envoy pour toi.1 Le bois dont il te parle est galement arriv ii.3 Quel excellent ouvrier il est, ceci est travaill avec un soin qui doit lui avoir demand normment de travail. Surtout la figure de femme est trs belle, en bois cir, tandis que les figures environnantes sont en bois rude & [1v:2] colories. Cest videmment bizarre & nexprime pas une ide bien nette mais cest beau comme un travail japonais, o galement il est difficile, au moins pour un europen, de saisir 1 The enclosed letter from Gauguin2 is letter 817. 3 For Gauguin4s Be in love, you will be happy , see letter 817, n. 13. 1 2 Theo van Gogh to Vincent van Gogh. Paris, Saturday, 16 November 1889. la signification, mais o il faut admirer les combinaisons de lignes & les beaux morceaux. Lensemble est dun ton tres sonore. Je voudrais bien que tu pouvais le voir. Tu laimerais certainement. Jai t cette semaine chez Bernard qui ma montr ce quil a fait dans le dernier temps. Je trouve quil a fait beaucoup de progrs. Son dessin est moins dtermin mais nexiste pas moins. Il y a plus de souplesse dans sa touche. -

Visions for the Viewer: the Influence of Two Unique Easel Paintings on the Late Murals of Pierre Puvis De Chavannes

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2018 Visions For The ieweV r: The nflueI nce Of Two Unique Easel Paintings On The Late Murals Of Pierre Puvis De Chavannes Geoffrey Neil David Thomas University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Thomas, G. N.(2018). Visions For The Viewer: The Influence Of Two Unique Easel Paintings On The Late Murals Of Pierre Puvis De Chavannes. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4899 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VISIONS FOR THE VIEWER: THE INFLUENCE OF TWO UNIQUE EASEL PAINTINGS ON THE LATE MURALS OF PIERRE PUVIS DE CHAVANNES by Geoffrey Neil David Thomas Bachelor of Science Wofford College, 2004 Bachelor of Arts Wofford College, 2006 _____________________________________________ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in Art History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2018 Accepted by: Andrew Graciano, Director of Thesis Bradford R. Collins, Reader Peter Chametzky, Reader Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Geoffrey Neil David Thomas, 2018 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION To Suzie and Neil Thomas, who generated my energy. To Jim Garrick and Peter Schmunk, who provided the spark to start the fire. -

Paul Gauguin's Genesis of a Picture: a Painter's Manifesto and Self-Analysis

Dario Gamboni Paul Gauguin's Genesis of a Picture: A Painter's Manifesto and Self-Analysis Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 2, no. 3 (Autumn 2003) Citation: Dario Gamboni, “Paul Gauguin's Genesis of a Picture: A Painter's Manifesto and Self- Analysis,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 2, no. 3 (Autumn 2003), http://www.19thc- artworldwide.org/autumn03/274-paul-gauguins-genesis-of-a-picture-a-painters-manifesto- and-self-analysis. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. ©2003 Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide Gamboni: Paul Gauguin‘s Genesis of a Picture: A Painter‘s Manifesto and Self-Analysis Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 2, no. 3 (Autumn 2003) Paul Gauguin's Genesis of a Picture: A Painter's Manifesto and Self-Analysis by Dario Gamboni Introduction There is an element of contradiction in the art historian's approach to interpreting the creative process. While artistic creativity is seen as stemming from the psychology of the creator, there is a tendency to deny the artist possession of direct or rational access to its understanding. Both attitudes have their roots in romantic art theory. These attitudes imply, on the one hand, that the artist's psyche is the locus of creation, and, on the other, that intuition and the unconscious play the major roles. Such ideas remained prevalent in the twentieth century, as attested, for example, by the famous talk given in April 1957 by Marcel Duchamp under the title "The Creative Act," which defined the artist as a "mediumistic being."[1] This element of contradiction explains the frequently ambivalent treatment of artists' accounts of their own creation: although we recognize that they possess a privileged and even unique position, we tend to dismiss their explanations as "rationalizations" and to prefer independent material evidence of the genesis of their works, such as studies or traces of earlier stages. -

Coastal Landscape with Sailboats Watercolour on Buff Paper, Laid Down on Card

Hippolyte Petitjean (1854 - 1929) Coastal Landscape with Sailboats Watercolour on buff paper, laid down on card. Signed hipp. Petitjean in blue ink at the lower right. 378 x 542 mm. (14 7/8 x 21 3/8 in.) From around 1912 onwards, Petitjean’s watercolours are characterized by more widely spaced dots of pure colour, in which the surface of the paper shows through. As one modern scholar has noted, ‘As with most of [Petitjean’s] works, his watercolors are not dated, nor are their locations identified. In executing them, he employed the divided color technique very freely, applying dabs of color in a loose network that allows the white of the paper to show through...in his pure landscapes the artist takes a more individual approach, subtly modulating the different areas of color to suggest gradual spatial recession or the light effects of a setting sun.’ The range and variety of Petitjean’s pointillist watercolours were only rediscovered several years after his death, at a centenary exhibition of the artist’s work held at the Galerie de l’Institut in Paris in 1955. A closely comparable pointillist watercolour of sailboats in a bay by Petitjean, of similar dimensions to the present sheet and signed in the same way, is in the collection of the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. Provenance: Private collection, France. Artist description: Hippolyte Petitjean left school at thirteen and began his training as a draughtsman in his native Mâcon while working as an apprentice housepainter. In 1872 he won a grant to study in Paris, where he continued his training at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, in the studio of the academic painter Alexandre Cabanel. -

Decorative Painting and Politics in France, 1890-1914

Decorative Painting and Politics in France, 1890-1914 by Katherine D. Brion A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History of Art) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Professor Howard Lay, Chair Professor Joshua Cole Professor Michèle Hannoosh Professor Susan Siegfried © Katherine D. Brion 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I will begin by thanking Howard Lay, who was instrumental in shaping the direction and final form of this dissertation. His unbroken calm and good-humor, even in the face of my tendency to take up new ideas and projects before finishing with the old, was of huge benefit to me, especially in the final stages—as were his careful and generous (re)readings of the text. Susan Siegfried and Michèle Hannoosh were also early mentors, first offering inspiring coursework and then, as committee members, advice and comments at key stages. Their feedback was such that I always wished I had solicited more, along with Michèle’s tea. Josh Cole’s seminar gave me a window not only into nineteenth-century France but also into the practice of history, and his kind yet rigorous comments on the dissertation are a model I hope to emulate. Betsy Sears has also been an important source of advice and encouragement. The research and writing of this dissertation was funded by fellowships and grants from the Georges Lurcy Foundation, the Rackham Graduate School at the University of Michigan, the Mellon Foundation, and the Getty Research Institute, as well as a Susan Lipschutz Award. My research was also made possible by the staffs at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the Institut nationale d’Histoire de l’Art, the Getty Research Library, the Musée des arts décoratifs/Musée de la Publicité, and the Musée Maurice Denis, ii among other institutions. -

Receptions of Toulouse-Lautrec's Reine De Joie Poster in the 1890S Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 8, No

Ruth E. Iskin Identity and Interpretation: Receptions of Toulouse-Lautrec’s Reine de joie Poster in the 1890s Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 8, no. 1 (Spring 2009) Citation: Ruth E. Iskin, “Identity and Interpretation: Receptions of Toulouse-Lautrec’s Reine de joie Poster in the 1890s,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 8, no. 1 (Spring 2009), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring09/63--identity-and-interpretation-receptions-of- toulouse-lautrecs-reine-de-joie-poster-in-the-1890s. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. ©2009 Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide Iskin: Receptions of Toulouse-Lautrec's Reine de joie Poster in the 1890s Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 8, no. 1 (Spring 2009) Identity and Interpretation: Receptions of Toulouse-Lautrec’s Reine de joie Poster in the 1890s by Ruth E. Iskin The ideology of the inexhaustible work of art, or of “reading” as re-creation, masks— through the quasi-exposure which is often seen in matters of faith—the fact that the work is indeed made not twice, but a hundred times, by all those who are interested in it, who find a material or symbolic profit in reading it, classifying it, deciphering it, commenting on it, combating it, knowing it, possessing it. Pierre Bourdieu.[1] Toulouse-Lautrec’s 1892 poster Reine de joie, which promoted a novel by that name, represents an elderly banker as a lascivious, balding, pot-bellied Jew whose ethnic nose is pinned down by a vigorous kiss from a dark-haired, red-lipped courtesan (fig.