Transitional Societies in Central Europe and Beyond Edited by Kai A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rural Youth Europe Magazine Rally Returned to Wales 14 Family 6 Farmers Around Europe Tell Their Stories

02 / 2014 European The Rural Youth Europe Magazine Rally returned to Wales 14 Family 6 farmers around Europe tell their stories Get to 12 know the new Board members Rural Youth Europe CONTENT Rural Youth Europe (RYEurope) is a European non- 3 Editors note governmental organisation for rural youth. Established in 1957, it is an umbrella for youth organisations working to promote and activate young people in 4-5 Going on in the countryside. It provides international training Europe possibilities and works as an intermediary between Meeting up with ECYC national organisations and youth organisations and Once an IFYE, always an public institutions at the European level. Rural Youth IFYE Greetings from Nordic Europe is a member-led organisation: democratically colleagues! constituted, the organisation is led by young people Lately in England: for young people. Rural Youth Europe unites 21 member organisations 6-9 Family farming across 18 European countries. The membership base is over 500,000 young people who either live in rural 10 Member areas or have an interest in rural life. greetings If your organisation is interested to join Rural Youth Europe or you would like more information about our 11 Our General events, please contact [email protected] Assembly or check our website www.ruralyoutheurope.com Kadri´s thank you text 12-13 New Board Rural Voices 14-17 European Rally is published by Rural Youth Europe. Views and opinions returned to expressed in this publication do not necessarily Wales reflect those of Rural Youth Europe. Text may include informal translations of statements and documents. 18-19 Updates Reproduction of articles is authorised provided the Rural Youth Project of the source is quoted and copies of the article are sent Year invitation to Rural Youth Europe. -

Rural Youth in Europe

Rural youth in Europe - All different all equal? Report of the study session held by RURAL YOUTH EUROPE (RYEurope) in co-operation with the European Youth Centre of the Council of Europe European Youth Centre Strasbourg 18 th œ 25 th February 2007 This report gives an account of various aspects of the study session. It has been produced by and is the responsibility of the educational team of the study session. It does not represent the official point of view of the Council of Europe. 2 DJS/S (2007) 2 June 2007 RRRuRuuurrrraaaallll yyyoyooouuuutttthhhh iiininnn EEEuEuuurrrrooooppppeeee --- AAAlAlllll dddidiiiffffffeeeerrrreeeennnntttt aaalalllll eeeqeqqquuuuaaaallll???? Report of the study session held by RURAL YOUTH EUROPE in co-operation with the European Youth Centre Strasbourg of the Council of Europe European Youth Centre Strasbourg 18 th œ 25 th February 2007 • Team Eija Kauniskangas (Finland) œ course director Janja Karner (Slovenia) Rhiannon Dafydd (UK) Kari Anne Grimelid Årset (Norway) Rudolf Grossfeld (Germany) Miquel Angel García López (Spain) œ external trainer • Editor Eija Kauniskangas Rural Youth Europe Allianssi-talo, Asemapäällikönkatu 1 FIN - 00520 Helsinki tel: +358 20 755 2631, fax: +358 20 755 2627 E-mail: [email protected] website: www.ruralyoutheurope.com 3 Dear Friends, This Study Session brought together young people from rural areas all over Europe to experience the differences and equalities that young people share in the rural areas. During the week we were dealing with different issues related to discrimination, human rights and intercultural learning in co operation with Council of Europe. This seminar has been a great learning experience for all of us, eye-opening for many involved parties and completely new for some participants to experience the situation of being discriminated against, challenging their own behaviour and views. -

Village International

F O R A L L N ! I O - S U L C N I - T E N . VILLAGE H T U W O W - Y W . S A L T O INTERNATIONAL A practical booklet for youth workers about set- ting up international projects in rural and geo- graphically isolated areas Download this and other SALTO Inclusion booklets for free at: www.SALTO-YOUTH.net/Inclusion/ SALTO-YOUTH INCLUSION RESOURCE CENTRE Education and Culture VILLAGE INTERNATIONAL This document does not necessarily refl ect the offi cial views of the European Commission or the SALTO Inclusion Resource Centre or the organisations cooperating with them. 2 SALTO-YOUTH STANDS FOR… …‘Support and Advanced Learning and Training Opportunities within the Youth in Action programme’. The European Commission has created a network of eight SALTO-YOUTH Resource Centres to enhance the implementation of the European Youth in Action programme which provides young people with valuable non-formal learning experiences. SALTO’s aim is to support European Youth in Action projects in priority areas such as European Citizenship, Cultural Diversity, Participation and Inclusion of young people with fewer oppor- tunities, in regions such as EuroMed, South-East Europe or Eastern Europe and the Caucasus, with Training and Cooperation activities and with Information tools for National Agencies. In these European priority areas, SALTO-YOUTH provides resources, information and training for National Agencies and European youth workers. Several resources in the above areas are available at www.SALTO-YOUTH.net. Find online the European Training Calendar, the Toolbox for Training and Youth Work, Trainers Online for Youth, links to online resources and much more… SALTO-YOUTH actively co-operates with other actors in European youth work such as the National Agencies of the Youth in Action programme, the Council of Europe, the European Youth Forum, European youth workers and trainers and training organisers. -

Rural Connections Spring /Summer 2019 1

ISSN 2443-7379 EN European Network for Rural Development RURAL SPRING/ SUMMER CONNECTIONS 2019 THE EUROPEAN RURAL DEVELOPMENT MAGAZINE NEWS AND UPDATES • GETTING SMART VILLAGES RIGHT • RURAL WOMEN IN EUROPE • PROMOTING THE RURAL BIOECONOMY RURAL ISSUES, RURAL PERSPECTIVES • EMPOWERING RURAL YOUTH • THE GREEN DANUBE • RURAL POLAND AND THE EU FOCUS ON… networX Funded by the https://enrd.ec.europa.eu European Network for Rural Development European Network for Rural Development The European Network for Rural Development (ENRD) is Each Member State has established a National Rural the hub that connects rural development stakeholders Network (NRN) that brings together the organisations and throughout the European Union (EU). The ENRD contributes administrations involved in rural development. At EU level, to the effective implementation of Member States’ Rural the ENRD supports the networking of these NRNs, national Development Programmes (RDPs) by generating and sharing administrations and European organisations. knowledge, as well as through facilitating information exchange and cooperation across rural Europe. Find out more on the ENRD website (https://enrd.ec.europa.eu) Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). Managing editor: Neda Skakelja, Head of Unit, EC Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development. Editor: Derek McGlynn, Publications Manager, ENRD Contact Point Manuscript text finalised during June 2019. Original version is the English text. More information on the European Union is available on the internet (http://europa.eu). -

European Youth Foundation

EUROPEAN YOUTH FOUNDATION 2017 Annual report EUROPEAN YOUTH FOUNDATION 2017 Annual report Prepared by the secretariat of the European Youth Foundation, Youth Department Directorate of Democratic Citizenship and Participation DG Democracy Council of Europe French edition: Le Fonds Européen pour la Jeunesse Rapport annuel 2017 All requests concerning the reproduction or translation of all or part of the document should be addressed to the Directorate of Communication (F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex or [email protected]). Cover and layout: All other correspondence concerning this Documents and publications document should be addressed to: production Department (SPDP), Council of Europe European Youth Foundation 30, rue Pierre de Coubertin Photos: Council of Europe, ©shutterstock F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex France © Council of Europe, February 2018 E-mail: [email protected] Printed at the Council of Europe CONTENTS THE EUROPEAN YOUTH FOUNDATION 5 Key figures 5 INTRODUCTION 7 PARTNER NGOs 9 EYF SUPPORT 10 1. Annual work plans 11 2. International activities 11 3. Pilot activities 11 4. Structural grants 12 5. Integrated grant 12 EYF PRIORITIES 13 1. Young people and decision-making 13 2. Young people’s access to rights 15 3. Intercultural dialogue and peacebuilding 16 4. Priorities for pilot activities 17 FLAGSHIP ACTIVITIES OF THE EYF 19 1. Visits to EYF-supported projects 19 2. EYF seminars 19 3. EYF information sessions 20 4. Other EYF presentations 20 SPECIFICITY OF THE EYF 21 1. Volunteer Time Recognition 21 2. Gender perspectives 21 3. Non-formal education -

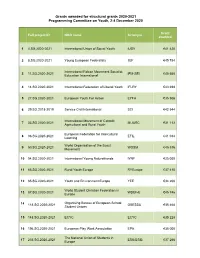

Structural Grants 2020-2021 Programming Committee on Youth, 2-4 December 2020

Grants awarded for structural grants 2020-2021 Programming Committee on Youth, 2-4 December 2020 Grant Full project ID NGO name Acronym awarded 1 4.SG.2020-2021 International Union of Social Youth IUSY €41 420 2 8.SG.2020-2021 Young European Federalists JEF €45 784 International Falcon Movement Socialist 3 11.SG.2020-2021 IFM-SEI €45 650 Education International 4 14.SG.2020-2021 International Federation of Liberal Youth IFLRY €43 698 5 27.SG.2020-2021 European Youth For Action EYFA €35 506 6 29.SG.2018-2019 Service Civil International SCI €42 544 International Movement of Catholic 7 33.SG.2020-2021 MIJARC €31 112 Agricultural and Rural Youth European Federation for Intercultural 8 36.SG.2020-2021 EFIL €41 034 Learning World Organisation of the Scout 9 50.SG.2020-2021 WOSM €45 516 Movement 10 54.SG.2020-2021 International Young Naturefriends IYNF €25 000 11 65.SG.2020-2021 Rural Youth Europe RYEurope €37 410 12 85.SG.2020-2021 Youth and Environment Europe YEE €34 208 World Student Christian Federation in 13 87.SG.2020-2021 WSCF-E €45 746 Europe Organising Bureau of European School 14 118.SG.2020-2021 OBESSU €35 468 Student Unions 15 148.SG.2020-2021 ECYC ECYC €35 228 16 196.SG.2020-2021 European Play Work Association EPA €36 000 The National Union of Students in 17 235.SG.2020-2021 ESU/ESIB €37 266 Europe International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, 18 236.SG.2020-2021 Transgender Queer and Intersex Youth IGLYO €45 890 and Student Organisation 19 261.SG.2020-2021 Youth of European Nationalities YEN JEV JC €46 160 20 278.SG.2020-2021 Youth for -

Report of the Study Session Held by Rural Youth Europe and European Council of Young Farmers in Co-Operation with the European Youth Centre of the Council of Europe

DDP/EYCB/RYE-CEJAStS/2019/27 Budapest, 11 June 2019 Report of the study session held by Rural Youth Europe and European Council of Young Farmers in co-operation with the European Youth Centre of the Council of Europe European Youth Centre Budapest This report gives an account of various aspects of the study session. It has been produced by and is the responsibility of the educational team of the study session. It does not represent the official point of view of the Council of Europe. Democritical Team: Eelin Hoffström-Cagiran RYEurope Course director Anja Mager RYEurope Facilitator Alessia Musumarra CEJA Facilitator Fiona Lally CEJA Facilitator Armine Movsesyan RYEurope Facilitator Jesse van de Woestijne Natalia Chardymova ECYB Educational advisor Rural Youth Europe +358 4523 45629 [email protected] www.ruralyoutheurope.com CEJA +32 (0)2 230 42 10 [email protected] www.ceja.eu Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 54 2. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 65 2.1 Background to the session ............................................................................................................ 65 2.2 Aims and objectives ...................................................................................................................... 65 2.3 Profile of the participants............................................................................................................. -

Engaging Rural Youth in Entrepreneurship Through Extracurricular and Co-Curricular Systems

Engaging Rural Youth in Entrepreneurship through Extracurricular and Co-curricular Systems Seth Heinert and T. Grady Roberts, University of Florida March 2016 USAID/BFS/ARP-Funded Project Award Number: AID-OAA-L-12-00002 Acknowledgements The Innovation in Agricultural Training and Education project—InnovATE—is tasked with compiling the best ideas on how to build the capacity of Agricultural Education and Training (AET) institutions and programs and disseminating them to AET practitioners around the world. As part of this effort, InnovATE issued a Call for Concept Notes to accept applications for discussion papers that address Contemporary Challenges in Agricultural Education and Training. These concept papers define the state of the art in the theory and practice of AET, in selected focus domains and explore promising strategies and practices for strengthening AET systems and institutions. This project was made possible by the United States Agency for International Development and the generous support of the American people through USAID Cooperative Agreement No. AID-OAA-L-12-00002 i Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................... i List of Boxes .................................................................................................................................... iii List of Figures .................................................................................................................................. iv Appendices -

Magazine 1/2013

01/2013 THE RURAL YOUTH EUROPE MAGAZINE Who won the Youth Project Once an IFYE – competition this year? always an IFYE Managing youth projects Check pages 04 –08 Read on page 09 Find out on page 14 www.ruralyoutheurope.com CONTENTS | 2 Rural p. 03 SPRING 2013 EDITION Youth 02 Contents p. 04 Europe 03 Editorial Brussels Rural Youth Europe (RYEurope) is a European non-governmental organisation for rural youth. 04-08 Youth Project of 2012 competition Established in 1957, it is an umbrella for youth p. 09 organisations working to promote and activate 09 Where are they now? young people in countryside. It provides international training possibilities and works as 10-11 Youth exchange in Finland an intermediary between national organisations and youth organisations and public institutions 12-13 IFYE exchange p. 10 at the European level. Rural Youth Europe is a member-led organisation: democratically 14 Managing youth a project constituted, the organisation is led by young people for young people. 15 Postcards p. 12 Rural Youth Europe aims to: 16 Calendar 2013 • Educate and train young people and create an awareness of rural and social issues. • Actively encourage rural populations and industry. p. 14 • Support the development of new rural youth organisations. • Network with other European NGOs. • Lobby and highlight the problems and needs of rural youth to focus the attention of inter - p. 15 national and national bodies, as well as the general public. Rural Youth Europe unites 26 member info – rural youth europe is published by Rural Youth Europe. Views and opinions expressed in this organisations across 21 European countries. -

'Pandemic Scar' on Young People

THE ‘PANDEMIC SCAR’ ON YOUNG PEOPLE The social, economic and mental health impact of COVID-19 on young people in Europe Acknowledgements This report was produced by People Dialogue and Change and commissioned by the European Youth Forum. Authors Dr. Dan Moxon, Cristina Bacalso and Dr. Adina Marina Șerban, with support from Alexandru-Rudol Ciuciu and Violetta Duncan. Editor Nikita Sanaullah With input from Flavia Colonnese and William Hayward About People Dialogue and Change People Dialogue and Change is a values driven company that specialises in supporting organisations to develop their approach to youth participation and youth engagement. We work with organisations in the public, voluntary and academic sector to provide research, evaluation, consultancy and capacity building services, across Europe and beyond. About the European Youth Forum The European Youth Forum is the platform of youth organisations in Europe. We represent over 100 youth organisations, which bring together tens of millions of young people from all over Europe. Acknowledgements The research team would like to thank the following people for their support with the project: All of the research participants Asociația “Ghi Lacho” Hunedoara Cansu Yılmaz & Asuman Tongarlak - Uluslararası Gençlik Dayanışma Derneği Deutscher Bundesjugendring ERGO Network European Disability Forum European Patient Forum European Platform on Multiple Sclerosis European Trade Union Confederation Youth Europe Youth Forum Board and Secretariat Jonas Bausch, Drew Gardiner, and Susana Puerto - International Labour Organisation Mladi + Musa Akgül Organising Bureau of European School Student Unions Rural Youth Europe © European Youth Forum 2021 European Youth Forum 10 Rue de l’Industrie 1000 Brussels, Belgium www.youthforum.org To cite this work: Moxon, D., Bacalso, C, and Șerban, A (2021), Beyond the pandemic: The impact of COVID-19 on young people in Europe. -

Magazine 2/2012

Rural-Info_02-2012_120927ok 27.09.12 15:07 Seite 1 02/2012 THE RURAL YOUTH EUROPE MAGAZINE Bridging the Age Gap in Budapest Check pages 4-5 Reaching your potential in Poland Read about the Rally on pages 6-7 How can you get a trophy for your best project? Find out on pages 14-15 Rural-Info_02-2012_120927ok 27.09.12 15:08 Seite 2 www.ruralyoutheurope.com C O N T E N T S | 2 AUTUMN 2012 EDITION p. 04 Rural 2 Rural Youth Europe intro Youth 3 Editorial p. 06 Europe 3 Time to say goodbye! 4-5 Spring Seminar 2012 Rural Youth Europe (RYEurope) is a European non-governmental organisation for rural youth. 6-7 Rally 2012 p. 08 Established in 1957, it is an umbrella for youth organisations working to promote and activate 8-9 General Assembly 2012 young people in countryside. It provides international training possibilities and works as 10-11 New Board an intermediary between national organisations p. 10 and youth organisations and public institutions 12-13 Youth exchange in Austria at the European level. Rural Youth Europe is a member-led organisation: democratically 14 Best Practice Competition 2012 constituted, the organisation is led by young people for young people. 15 Postcards p. 12 Study trip to Bulgaria Rural Youth Europe aims to: IFYE conference in Sweden • Educate and train young people and create an awareness of rural and social issues. 16 Calendar 2012-2013 • Actively encourage rural populations and p. 14 industry. • Support the development of new rural youth organisations. • Network with other European NGOs. -

Annual Report 2018

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 WELCOME HIGHLIGHTS OUR NUMBERS WELCOME OUR IMPACT OUR MEMBERS OUR RESOURCES Luìs Alvarado Martìnez President OUR PEOPLE Anna Widegren Secretary General 2018: a year that brought celebrations, positive change in the cities themselves but As we look to the future we must be ready to breakthroughs and powerful moments for in others across Europe as they share ideas, stand up for the realities and challenges still young people. While challenges remain experiences and best practices. The creation facing young people across all aspects of their on the horizon and new threats for Europe of new and improved co-decision-making lives: from navigating the precarious transition and our planet are imminent, we must not structures was highlighted as one of the main from education to work, to fighting against underestimate the significant advancements benefits for the title winners in our ten year multiple discrimination, social exclusion, that the European Youth Forum and our report. We can’t wait to spark the evolution poverty and lack of representation. As our new Member Organisations have made this year. of more innovative, youthful cities as we look Youth Progress Index shows, our societies still ahead to ten more years of the European have a long way to go to meaningfully include We are starting to witness the world waking Youth Capital - and beyond! youth voices. Empowering young people and up to the reality of youth rights. Through our their communities to support other displaced work with the United Nations we are proud This year our biggest event of the year got young people was also a significant focus of that for the first time young people are being even bigger.