Uncertainty and Graphicacy How Should Statisticians, Journalists, and Designers Reveal Uncertainty in Graphics for Public Consumption?

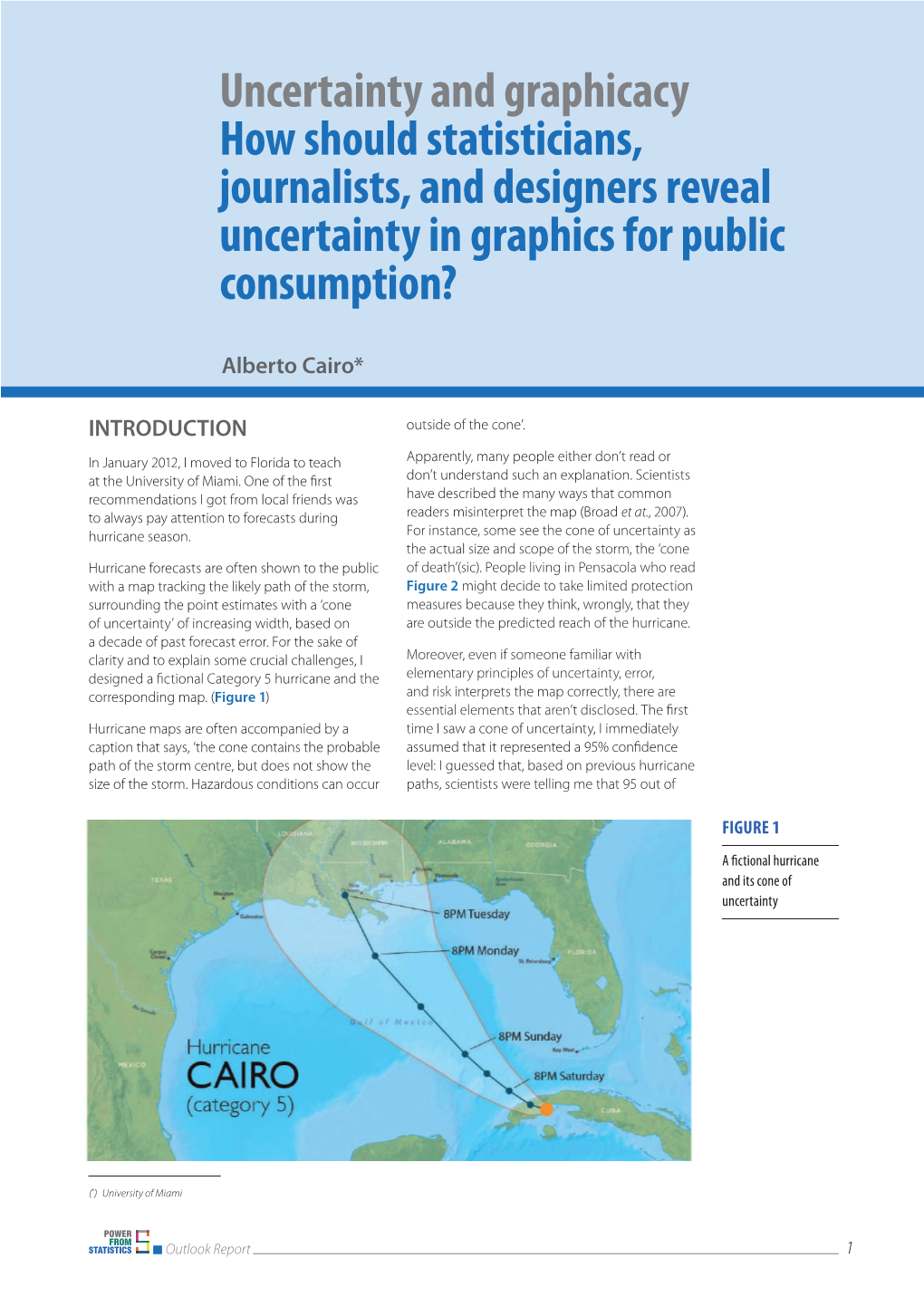

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minard's Chart of Napolean's Campaign

Minard's Chart of Napolean's Campaign Charles Joseph Minard (French: [minaʁ]; 27 March 1781 – 24 October 1870) was a French civil engineer recognized for his significant contribution in the field of information graphics in civil engineering and statistics. Minard was, among other things, noted for his representation of numerical data on geographic maps. Charles Minard's map of Napoleon's disastrous Russian campaign of 1812. The graphic is notable for its representation in two dimensions of six types of data: the number of Napoleon's troops; distance; temperature; the latitude and longitude; direction of travel; and location relative to specific dates.[2] Wikipedia (n.d.). Charles Minard's 1869 chart showing the number of men in Napoleon’s 1812 Russian campaign army, their movements, as well as the temperature they encountered on the return path. File:Minard.png. https:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Minard.png The original description in French accompanying the map translated to English:[3] Drawn by Mr. Minard, Inspector General of Bridges and Roads in retirement. Paris, 20 November 1869. The numbers of men present are represented by the widths of the colored zones in a rate of one millimeter for ten thousand men; these are also written beside the zones. Red designates men moving into Russia, black those on retreat. — The informations used for drawing the map were taken from the works of Messrs. Thiers, de Ségur, de Fezensac, de Chambray and the unpublished diary of Jacob, pharmacist of the Army since 28 October. Recognition Modern information -

Time and Animation

TIME AND ANIMATION Petra Isenberg (&Pierre Dragicevic) TIME VISUALIZATION ANIMATION 2 TIME VISUALIZATION ANIMATION Time 3 VISUALIZATION OF TIME 4 TIME Is just another data dimension Why bother? 5 TIME Is just another data dimension Why bother? What data type is it? • Nominal? • Ordinal? • Quantitative? 6 TIME Ordinal Quantitative • Discrete • Continuous Aigner et al, 2011 7 TIME Joe Parry, 2007. Adapted from Mackinlay, 1986 8 TIME Periodicity • Natural: days, seasons • Social: working hours, holidays • Biological: circadian, etc. Has many subdivisions (units) • Years, months, days, weeks, H, M, S Has a specific meaning • Not captured by data type • Associations, conventions • Pervasive in the real-world • Time visualizations often considered as a separate type 9 TIME Shneiderman: • 1-dimensional data • 2-dimensional data • 3-dimensional data • temporal data • multi-dimensional data • tree data • network data 10 VISUALIZING TIME as a time point 11 VISUALIZING TIME as a time period 12 VISUALIZING TIME as a duration 13 VISUALIZING TIME PLUS DATA 14 MAPPING TIME TO SPACE 15 MAPPING TIME TO AN AXIS Time Data 16 TIME-SERIES DATA From a Statistics Book: • A set of observations xt, each one being recorded at a specific time t From Wikipedia: • A sequence of data points, measured typically at successive time instants spaced at uniform time intervals 17 LINE CHARTS Aigner et al, 2011 18 LINE CHARTS Marey’s Physiological Recordings Plethysmograph Étienne-Jules Marey, 1876 (image source) Pneumogram Étienne-Jules Marey, 1876 (image source) 19 LINE CHARTS Pendulum Seismometer (image source) Andrea Bina, 1751 Possibly also 17th century (source) 20 LINE CHARTS Inclinations of planetary orbits Macrobius, 10th or 11th century cited in Kendall, 1990 21 Marey’s Train Schedule LINE CHARTS 6 PARIS LYON 7 22 Étienne-Jules Marey, 1885, cited in Tufte, 1983 OTHER CHARTS Line Plots Point Plots Silhouette Graphs Bar Charts Aigner et al, 2011 23 OTHER CHARTS Combination - New York Times Weather Chart New York Times, 1980. -

Defining Visual Rhetorics §

DEFINING VISUAL RHETORICS § DEFINING VISUAL RHETORICS § Edited by Charles A. Hill Marguerite Helmers University of Wisconsin Oshkosh LAWRENCE ERLBAUM ASSOCIATES, PUBLISHERS 2004 Mahwah, New Jersey London This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2008. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” Copyright © 2004 by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microform, retrieval system, or any other means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Publishers 10 Industrial Avenue Mahwah, New Jersey 07430 Cover photograph by Richard LeFande; design by Anna Hill Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Definingvisual rhetorics / edited by Charles A. Hill, Marguerite Helmers. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8058-4402-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 0-8058-4403-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Visual communication. 2. Rhetoric. I. Hill, Charles A. II. Helmers, Marguerite H., 1961– . P93.5.D44 2003 302.23—dc21 2003049448 CIP ISBN 1-4106-0997-9 Master e-book ISBN To Anna, who inspires me every day. —C. A. H. To Emily and Caitlin, whose artistic perspective inspires and instructs. —M. H. H. Contents Preface ix Introduction 1 Marguerite Helmers and Charles A. Hill 1 The Psychology of Rhetorical Images 25 Charles A. Hill 2 The Rhetoric of Visual Arguments 41 J. Anthony Blair 3 Framing the Fine Arts Through Rhetoric 63 Marguerite Helmers 4 Visual Rhetoric in Pens of Steel and Inks of Silk: 87 Challenging the Great Visual/Verbal Divide Maureen Daly Goggin 5 Defining Film Rhetoric: The Case of Hitchcock’s Vertigo 111 David Blakesley 6 Political Candidates’ Convention Films:Finding the Perfect 135 Image—An Overview of Political Image Making J. -

The Golden Age of Statistical Graphics

The Golden Age of Statistical Graphics Michael Friendly Psychology Department and Statistical Consulting Service York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ON, Canada M3J 1P3 in: Statistical Science. See also BIBTEX entry below. BIBTEX: @Article{Friendly:2008:golden, author = {Michael Friendly}, title = {The {Golden Age} of Statistical Graphics}, journal = {Statistical Science}, year = {2008}, volume = {}, number = {}, pages = {}, url = {http://www.math.yorku.ca/SCS/Papers/golden.pdf}, note = {in press (accepted 8-Sep-08)}, } © copyright by the author(s) document created on: September 8, 2008 created from file: golden.tex cover page automatically created with CoverPage.sty (available at your favourite CTAN mirror) In press, Statistical Science The Golden Age of Statistical Graphics Michael Friendly∗ September 8, 2008 Abstract Statistical graphics and data visualization have long histories, but their modern forms began only in the early 1800s. Between roughly 1850 to 1900 ( 10), an explosive oc- curred growth in both the general use of graphic methods and the range± of topics to which they were applied. Innovations were prodigious and some of the most exquisite graphics ever produced appeared, resulting in what may be called the “Golden Age of Statistical Graphics.” In this article I trace the origins of this period in terms of the infrastructure required to produce this explosive growth: recognition of the importance of systematic data collection by the state; the rise of statistical theory and statistical thinking; enabling developments -

RUNNING HEAD: Turkish Emotional Word Norms

RUNNING HEAD: Turkish Emotional Word Norms Turkish Emotional Word Norms for Arousal, Valence, and Discrete Emotion Categories Aycan Kapucu1, Aslı Kılıç2, Yıldız Özkılıç Kartal3, and Bengisu Sarıbaz1 1 Department of Psychology, Ege University 2 Department of Psychology, Middle Eastern Technical University 3Department of Psychology, Uludag University Figures: 3 Tables: 5 Corresponding Author: Aycan Kapucu Department of Psychology, Ege University Ege Universitesi Edebiyat Fakultesi Psikoloji Bolumu, Kampus, Bornova, 35400, Izmir, Turkey Phone: +902323111340 Email: [email protected] Turkish Emotional Word Norms 2 Abstract The present study combined dimensional and categorical approaches to emotion to develop normative ratings for a large set of Turkish words on two major dimensions of emotion: arousal and valence, as well as on five basic emotion categories of happiness, sadness, anger, fear, and disgust. A set of 2031 Turkish words obtained by translating ANEW (Bradley & Lang, 1999) words to Turkish and pooling from the Turkish Word Norms (Tekcan & Göz, 2005) were rated by a large sample of 1685 participants. This is the first comprehensive and standardized word set in Turkish offering discrete emotional ratings in addition to dimensional ratings along with concreteness judgments. Consistent with ANEW and word databases in several other languages, arousal increased as valence became more positive or more negative. As expected, negative emotions (anger, sadness, fear, and disgust) were positively correlated with each other; whereas the -

The Forgotten Discovery of Gravity Models and the Inefficiency of Early

The forgotten discovery of gravity models and the inefficiency of early railway networks Andrew Odlyzko School of Mathematics University of Minnesota Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA [email protected] http://www.dtc.umn.edu/∼odlyzko Revised version, April 19, 2015 Abstract. The routes of early railways around the world were generally inef- ficient because of the incorrect assumption that long distance travel between major cities would dominate. Modern planners rely on methods such as the “gravity models of spatial interaction,” which show quantitatively the impor- tance of accommodating travel demands between smaller cities. Such models were not used in the 19th century. This paper shows that gravity models were discovered in 1846, a dozen years earlier than had been known previously. That discovery was published during the great Railway Mania in Britain. Had the validity and value of gravity models been recognized properly, the investment losses of that gigantic bubble could have been lessened, and more efficient rail systems in Britain and many other countries would have been built. This incident shows society’s early encounter with the “Big Data” of the day and the slow diffusion of economically significant information. The results of this study suggest that it will be increasingly feasible to use modern network science to analyze information dissemination in the 19th century. That might assist in understanding the diffusion of technologies and the origins of bubbles. Keywords: gravity models, railway planning, diffusion of information JEL classification codes: D8, L9, N7 1 Introduction Dramatic innovations in transportation or communication frequently produce predictions that distance is becoming irrelevant. In recent decades, two popular books in this genre introduced the concepts of “death of distance” [7] and “the Earth is flat” [25]. -

Visions and Re-Visions of Charles Joseph Minard

Visions and Re-Visions of Charles Joseph Minard Michael Friendly Psychology Department and Statistical Consulting Service York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ON, Canada M3J 1P3 in: Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. See also BIBTEX entry below. BIBTEX: @Article{ Friendly:02:Minard, author = {Michael Friendly}, title = {Visions and {Re-Visions} of {Charles Joseph Minard}}, year = {2002}, journal = {Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics}, volume = {27}, number = {1}, pages = {31--51}, } © copyright by the author(s) document created on: February 19, 2007 created from file: jebs.tex cover page automatically created with CoverPage.sty (available at your favourite CTAN mirror) JEBS, 2002, 27(1), 31–51 Visions and Re-Visions of Charles Joseph Minard∗ Michael Friendly York University Abstract Charles Joseph Minard is most widely known for a single work, his poignant flow-map depiction of the fate of Napoleon’s Grand Army in the disasterous 1812 Russian campaign. In fact, Minard was a true pioneer in thematic cartography and in statistical graphics; he developed many novel graphics forms to depict data, always with the goal to let the data “speak to the eyes.” This paper reviews Minard’s contributions to statistical graphics, the time course of his work, and some background behind the famous March on Moscow graphic. We also look at some modern re-visions of this graph from an information visualization perspecitive, and examine some lessons this graphic provides as a test case for the power and expressiveness of computer systems or languages for graphic information display and visual- ization. Key words: Statistical graphics; Data visualization, history; Napoleonic wars; Thematic car- tography; Dynamic graphics; Mathematica 1 Introduction RE-VISION n. -

STAT 6560 Graphical Methods

STAT 6560 Graphical Methods Spring Semester 2009 Project One Jessica Anderson Utah State University Department of Mathematics and Statistics 3900 Old Main Hill Logan, UT 84322{3900 CHARLES JOSEPH MINARD (1781-1870) And The Best Statistical Graphic Ever Drawn Citations: How others rate Minard's Flow Map of Napolean's Russian Campaign of 1812 . • \the best statistical graphic ever drawn" - (Tufte (1983), p. 40) • Etienne-Jules Marey said \it defies the pen of the historian in its brutal eloquence" -(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Joseph_Minard) • Howard Wainer nominated it as the \World's Champion Graph" - (Wainer (1997) - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Joseph_Minard) Brief background • Born on March 27, 1781. • His father taught him to read and write at age 4. • At age 6 he was taught a course on anatomy by a doctor. • Minard was highly interested in engineering, and at age 16 entered a school of engineering to begin his studies. • The first part of his career mostly consisted of teaching and working as a civil engineer. Gradually he became more research oriented and worked on private research thereafter. • By the end of his life, Minard believed he had been the co-inventor of the flow map technique. He wrote he was pleased \at having given birth in my old age to a useful idea..." - (Robinson (1967), p. 104) What was done before Minard? Examples: • Late 1700's: Mathematical and chemical graphs begin to appear. 1 • William Playfair's 1801:(Chart of the National Debt of England). { This line graph shows the increases and decreases of England's national debt from 1699 to 1800. -

Charles Joseph Minard: Mapping Napoleon's March, 1861

UC Santa Barbara CSISS Classics Title Charles Joseph Minard, Mapping Napoleon's March, 1861. CSISS Classics Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4qj8h064 Author Corbett, John Publication Date 2001 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California CSISS Classics - Charles Joseph Minard: Mapping Napoleon's March, 1861 Charles Joseph Minard: Mapping Napoleon's March, 1861 By John Corbett Background "It may well be the best statistical graphic ever drawn." Charles Joseph Minard's 1861 thematic map of Napoleon's ill-fated march on Moscow was thus described by Edward Tufte in his acclaimed 1983 book, The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. Of all the attempts to convey the futility of Napoleon's attempt to invade Russia and the utter destruction of his Grande Armee in the last months of 1812, no written work or painting presents such a compelling picture as does Minard's graphic. Charles Joseph Minard's Napoleon map, along with several dozen others that he published during his lifetime, set the standard for excellence in graphically depicting flows of people and goods in space, yet his role in the development of modern thematic mapping techniques is all too often overlooked. Minard was born in Dijon in 1781, and quickly gained a reputation as one of the leading French canal and harbor engineers of his time. In 1810, he was one of the first engineers to empty water trapped by cofferdams using relatively new steam-powered technology. In 1830 Minard began a long association with the prestigious École des Ponts et Chatussées, first as superintendent, and later as a professor and inspector. -

Visualiation of Quantitative Information

Visualisation of quantitative information Overview 1. Visualisation 2. Approaching data 3. Levels of measurement 4. Principals of graphing 5. Univariate graphs 6. Graphical integrity James Neill, 2011 2 Is Pivot a turning point for web exploration? (Gary Flake) (TED talk - 6 min. ) 4 Approaching Entering & data screening Approaching Exploring, describing, & data graphing Hypothesis testing 5 6 Describing & graphing data THE CHALLENGE: to find a meaningful, accurate way to depict the ‘true story’ of the data 7 Clearly report the data's main features 10 Levels of measurement • Nominal / Categorical • Ordinal • Interval • Ratio 12 Discrete vs. continuous Discrete - - - - - - - - - - Continuous ___________ Each level has the properties of the preceding 14 13 levels, plus something more! Categorical / nominal Ordinal / ranked scale • Conveys a category label • Conveys order , but not distance • (Arbitrary) assignment of #s to e.g. in a race, 1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc. or categories ranking of favourites or preferences e.g. Gender • No useful information, except as labels 15 16 Ordinal / ranked example: Ranked importance Interval scale Rank the following aspects of the university according to what is most • Conveys order & distance important to you (1 = most important • 0 is arbitrary through to 5 = least important) e.g., temperature (degrees C) __ Quality of the teaching and education • Usually treat as continuous for > 5 __ Quality of the social life intervals __ Quality of the campus __ Quality of the administration __ Quality of the university's reputation 17 18 Interval example: 8 point Likert scale Ratio scale • Conveys order & distance • Continuous, with a meaningful 0 point e.g. height, age, weight, time, number of times an event has occurred • Ratio statements can be made e.g. -

A Brief History of Data Visualization

ABriefHistory II.1 of Data Visualization Michael Friendly 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................ 16 1.2 Milestones Tour ................................................................................... 17 Pre-17th Century: Early Maps and Diagrams ............................................. 17 1600–1699: Measurement and Theory ..................................................... 19 1700–1799: New Graphic Forms .............................................................. 22 1800–1850: Beginnings of Modern Graphics ............................................ 25 1850–1900: The Golden Age of Statistical Graphics................................... 28 1900–1950: The Modern Dark Ages ......................................................... 37 1950–1975: Rebirth of Data Visualization ................................................. 39 1975–present: High-D, Interactive and Dynamic Data Visualization ........... 40 1.3 Statistical Historiography .................................................................. 42 History as ‘Data’ ...................................................................................... 42 Analysing Milestones Data ...................................................................... 43 What Was He Thinking? – Understanding Through Reproduction.............. 45 1.4 Final Thoughts .................................................................................... 48 16 Michael Friendly It is common to think of statistical graphics and data -

3D Visualization of Cadastre: Assessing the Suitability of Visual Variables and Enhancement Techniques in the 3D Model of Condominium Property Units

3D Visualization of Cadastre: Assessing the Suitability of Visual Variables and Enhancement Techniques in the 3D Model of Condominium Property Units Thèse Chen Wang Doctorat en sciences géomatiques Philosophiæ doctor (Ph.D.) Québec, Canada © Chen Wang, 2015 3D Visualization of Cadastre: Assessing the Suitability of Visual Variables and Enhancement Techniques in the 3D Model of Condominium Property Units Thèse Chen Wang Sous la direction de : Jacynthe Pouliot, directrice de recherche Frédéric Hubert, codirecteur de recherche Résumé La visualisation 3D de données cadastrales a été exploitée dans de nombreuses études, car elle offre de nouvelles possibilités d’examiner des situations de supervision verticale des propriétés. Les chercheurs actifs dans ce domaine estiment que la visualisation 3D pourrait fournir aux utilisateurs une compréhension plus intuitive d’une situation où des propriétés se superposent, ainsi qu’une plus grande capacité et avec moins d’ambiguïté de montrer des problèmes potentiels de chevauchement des unités de propriété. Cependant, la visualisation 3D est une approche qui apporte de nombreux défis par rapport à la visualisation 2D. Les précédentes recherches effectuées en cadastre 3D, et qui utilisent la visualisation 3D, ont très peu enquêté l’impact du choix des variables visuelles (ex. couleur, style) sur la prise de décision. Dans l’optique d'améliorer la visualisation 3D de données cadastres, cette thèse de doctorat examine l’adéquation du choix des variables visuelles et des techniques de rehaussement associées afin de produire un modèle de condominium 3D optimal, et ce, en fonction de certaines tâches spécifiques de visualisation. Les tâches visées sont celles dédiées à la compréhension dans l’espace 3D des limites de propriété du condominium.