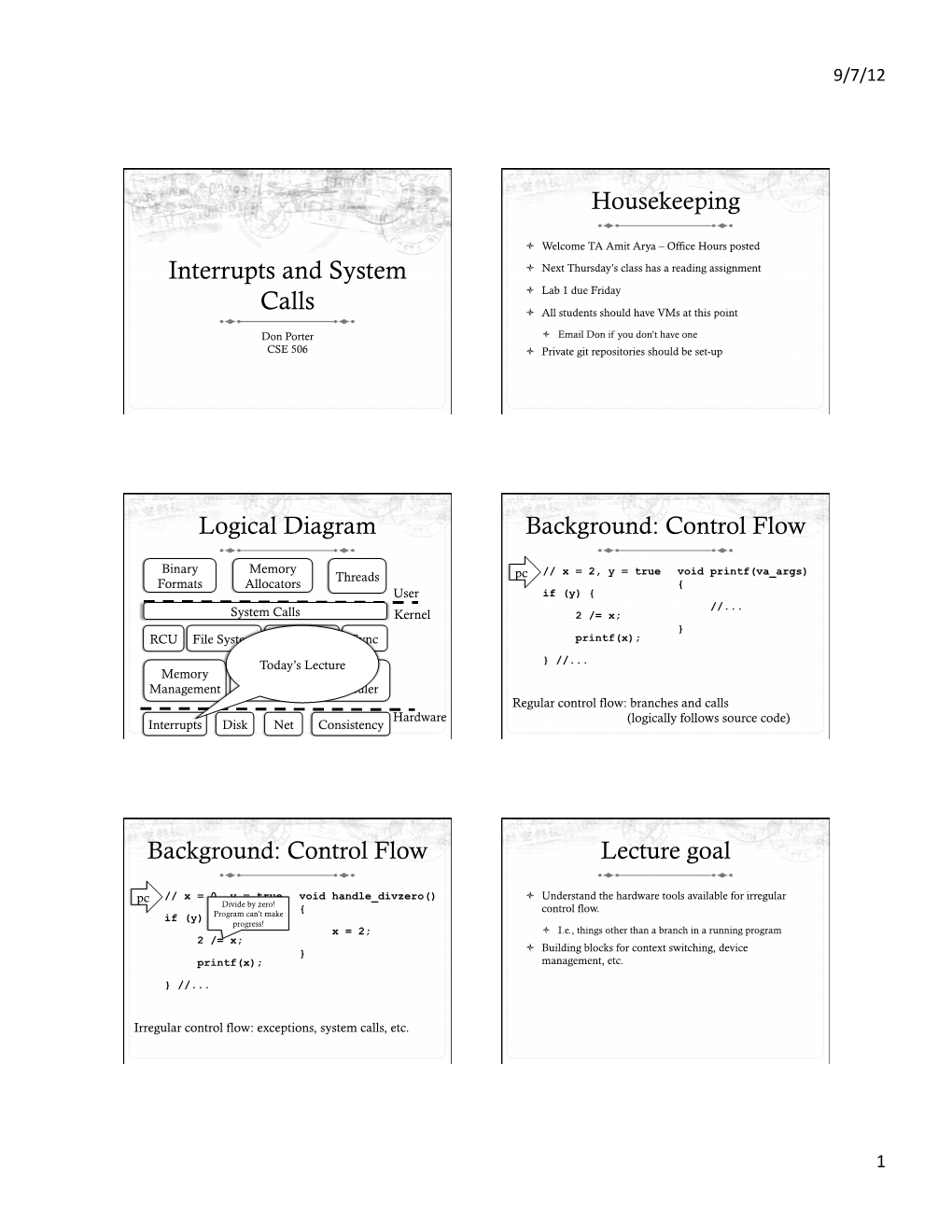

Interrupts and System Calls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interrupt Handling in Linux

Department Informatik Technical Reports / ISSN 2191-5008 Valentin Rothberg Interrupt Handling in Linux Technical Report CS-2015-07 November 2015 Please cite as: Valentin Rothberg, “Interrupt Handling in Linux,” Friedrich-Alexander-Universitat¨ Erlangen-Nurnberg,¨ Dept. of Computer Science, Technical Reports, CS-2015-07, November 2015. Friedrich-Alexander-Universitat¨ Erlangen-Nurnberg¨ Department Informatik Martensstr. 3 · 91058 Erlangen · Germany www.cs.fau.de Interrupt Handling in Linux Valentin Rothberg Distributed Systems and Operating Systems Dept. of Computer Science, University of Erlangen, Germany [email protected] November 8, 2015 An interrupt is an event that alters the sequence of instructions executed by a processor and requires immediate attention. When the processor receives an interrupt signal, it may temporarily switch control to an inter- rupt service routine (ISR) and the suspended process (i.e., the previously running program) will be resumed as soon as the interrupt is being served. The generic term interrupt is oftentimes used synonymously for two terms, interrupts and exceptions [2]. An exception is a synchronous event that occurs when the processor detects an error condition while executing an instruction. Such an error condition may be a devision by zero, a page fault, a protection violation, etc. An interrupt, on the other hand, is an asynchronous event that occurs at random times during execution of a pro- gram in response to a signal from hardware. A proper and timely handling of interrupts is critical to the performance, but also to the security of a computer system. In general, interrupts can be emitted by hardware as well as by software. Software interrupts (e.g., via the INT n instruction of the x86 instruction set architecture (ISA) [5]) are means to change the execution context of a program to a more privileged interrupt context in order to enter the kernel and, in contrast to hardware interrupts, occur synchronously to the currently running program. -

16-Bit MS-DOS Programming (MS-DOS & BIOS-Level Programming )

Microprocessors (0630371) Fall 2010/2011 – Lecture Notes # 20 16-Bit MS-DOS Programming (MS-DOS & BIOS-level Programming ) Objectives Real-Address Mode MS-DOS Memory Organization MS-DOS Memory Map Interrupts Mechanism—Introduction Interrupts Mechanism — Steps Types of Interrupts 8086/8088 Pinout Diagrams Redirecting Input-Output INT Instruction Interrupt Vectoring Process Common Interrupts Real-Address Mode Real-address mode (16-bit mode) programs have the following characteristics: o Max 1 megabyte addressable RAM o Single tasking o No memory boundary protection o Offsets are 16 bits IBM PC-DOS: first Real-address OS for IBM-PC Later renamed to MS-DOS, owned by Microsoft MS-DOS Memory Organization Interrupt Vector Table BIOS & DOS data Software BIOS MS-DOS kernel Resident command processor Transient programs Video graphics & text Reserved (device controllers) ROM BIOS MS-DOS Memory Map Address FFFFF R O M BIO S F0000 Reserved C0000 Video Text & Graphics B8000 V R A M Video Graphics A0000 Transient Command Processor Transient Program Area (available for application programs) Resident Command Processor 640K R A M DOS Kernel, Device Drivers Software BIOS BIOS & DOS Data 00400 Interrupt Vector Table 00000 Interrupt Mechanism—Introduction Devices such as the keyboard, the monitor, hard disks etc. can cause such interrupts, when they require service of some kind, such as to get or receive a byte. For example, when you press a key on the keyboard this causes an interrupt. When the Microprocessor is interrupted, it completes the current instruction, and then pushes onto the stack the flags register plus the address of the next instruction (the return address). -

Lesson-2: Interrupt and Interrupt Service Routine Concept

DEVICE DRIVERS AND INTERRUPTS SERVICE MECHANISM Lesson-2: Interrupt and Interrupt Service Routine Concept Chapter 6 L2: "Embedded Systems- Architecture, Programming and Design", 2015 1 Raj Kamal, Publs.: McGraw-Hill Education Interrupt Concept • Interrupt means event, which invites attention of the processor on occurrence of some action at hardware or software interrupt instruction event. Chapter 6 L2: "Embedded Systems- Architecture, Programming and Design", 2015 2 Raj Kamal, Publs.: McGraw-Hill Education Action on Interrupt In response to the interrupt, a routine or program (called foreground program), which is running presently interrupts and an interrupt service routine (ISR) executes. Chapter 6 L2: "Embedded Systems- Architecture, Programming and Design", 2015 3 Raj Kamal, Publs.: McGraw-Hill Education Interrupt Service Routine ISR is also called device driver in case of the devices and called exception or signal or trap handler in case of software interrupts Chapter 6 L2: "Embedded Systems- Architecture, Programming and Design", 2015 4 Raj Kamal, Publs.: McGraw-Hill Education Interrupt approach for the port or device functions Processor executes the program, called interrupt service routine or signal handler or trap handler or exception handler or device driver, related to input or output from the port or device or related to a device function on an interrupt and does not wait and look for the input ready or output completion or device-status ready or set Chapter 6 L2: "Embedded Systems- Architecture, Programming and Design", -

Additional Functions in HW-RTOS Offering the Low Interrupt Latency

HW-RTOS Real Time OS in Hardware Additional Functions in HW-RTOS Offering the Low Interrupt Latency In this white paper, we introduce two HW-RTOS functions that offer the lowest interrupt latency available and help create a more software-friendly environment. One of these is ISR implemented in hardware, which improves responsiveness when activating a task from an interrupt and eliminates the need for developing a handler in software. The other is a function allowing the use of non-OS managed interrupt handlers in a multitasking environment. This makes it easier to migrate from a non-RTOS environment to a multitasking one. R70WP0003EJ0100 September, 2018 2 / 8 Multitasking Environment with Lowest Interrupt Latency Offered by HW-RTOS 1. Executive Summary In this white paper, we introduce two functions special to HW-RTOS that improve interrupt performance. The first is the HW ISR function. Renesas stylized the ISR (Interrupt Service Routine) process and implemented it in hardware to create their HW ISR. With this function, the task corresponding to the interrupt signal can be activated directly and in real time. And, since the ISR is implemented in the hardware, application software engineers are relieved of the burden of developing a handler. The second is called Direct Interrupt Service. This function is equivalent to allowing a non-OS managed interrupt handler to invoke an API. This function %" "$# $""%!$ $ $""%!$!" enables synchronization and communication "$ "$ between the non-OS managed interrupt handler and $($ $($ '$ '$ tasks, a benefit not available in conventional $ $ software. In other words, it allows the use of non-OS # $ % " "$) ) managed interrupt handlers in a multitasking $($ '$ environment. -

Exceptions and Processes

Exceptions and Processes! Jennifer Rexford! The material for this lecture is drawn from! Computer Systems: A Programmerʼs Perspective (Bryant & O"Hallaron) Chapter 8! 1 Goals of this Lecture! •#Help you learn about:! •# Exceptions! •# The process concept! … and thereby…! •# How operating systems work! •# How applications interact with OS and hardware! The process concept is one of the most important concepts in systems programming! 2 Context of this Lecture! Second half of the course! Previously! Starting Now! C Language! Application Program! language! service! levels! Assembly Language! levels! Operating System! tour! tour! Machine Language! Hardware! Application programs, OS,! and hardware interact! via exceptions! 3 Motivation! Question:! •# How does a program get input from the keyboard?! •# How does a program get data from a (slow) disk?! Question:! •# Executing program thinks it has exclusive control of CPU! •# But multiple programs share one CPU (or a few CPUs)! •# How is that illusion implemented?! Question:! •# Executing program thinks it has exclusive use of memory! •# But multiple programs must share one memory! •# How is that illusion implemented?! Answers: Exceptions…! 4 Exceptions! •# Exception! •# An abrupt change in control flow in response to a change in processor state! •# Examples:! •# Application program:! •# Requests I/O! •# Requests more heap memory! •# Attempts integer division by 0! •# Attempts to access privileged memory! Synchronous! •# Accesses variable that is not$ in real memory (see upcoming $ “Virtual Memory” lecture)! •# User presses key on keyboard! Asynchronous! •# Disk controller finishes reading data! 5 Exceptions Note! •# Note:! ! !Exceptions in OS % exceptions in Java! Implemented using! try/catch! and throw statements! 6 Exceptional Control Flow! Application! Exception handler! program! in operating system! exception! exception! processing! exception! return! (optional)! 7 Exceptions vs. -

Programmable Logic Controllers Interrupt Basics

Programmable Logic Controllers Interrupts Electrical & Computer Engineering Dr. D. J. Jackson Lecture 13-1 Interrupt Basics In terms of a PLC What is an interrupt? When can the controller operation be interrupted? Priority of User Interrupts Interrupt Latency Interrupt Instructions Electrical & Computer Engineering Dr. D. J. Jackson Lecture 13-2 13-1 What is an Interrupt? • An interrupt is an event that causes the controller to suspend the task it is currently performing, perform a different task, and then return to the suspended task at the point where it suspended. • The Micrologix PLCs support the following User Interrupts: – User Fault Routine – Event Interrupts (4) – High-Speed Counter Interrupts(1) – Selectable Timed Interrupt Electrical & Computer Engineering Dr. D. J. Jackson Lecture 13-3 Interrupt Operation • An interrupt must be configured and enabled to execute. When any one of the interrupts is configured (and enabled) and subsequently occurs, the user program: 1. suspends its execution 2. performs a defined task based upon which interrupt occurred 3. returns to the suspended operation. Electrical & Computer Engineering Dr. D. J. Jackson Lecture 13-4 13-2 Interrupt Operation (continued) • Specifically, if the controller program is executing normally and an interrupt event occurs: 1. the controller stops its normal execution 2. determines which interrupt occurred 3. goes immediately to rung 0 of the subroutine specified for that User Interrupt 4. begins executing the User Interrupt subroutine (or set of subroutines if the specified subroutine calls a subsequent subroutine) 5. completes the subroutine(s) 6. resumes normal execution from the point where the controller program was interrupted Electrical & Computer Engineering Dr. -

Interrupt Handling

Namn: Laborationen godkänd: Computer Organization 6 hp Interrupt handling Purpose The purpose of this lab assignment is to give an introduction to interrupts, i.e. asynchronous events caused by external devices to which the processor may need to respond. One should learn how to write (1) initialization procedures for the devices that can cause interrupts, (2) initialization procedures for the processor such that it can respond to interrupts caused by different external devices and (3) interrupt handlers, i.e. different routines that should be executed as a response to the interrupts that have been caused by any of the different external devices. Interrupts An interrupt refers to an external event that needs immediate attention from the processor. An interrupt signals the processor, indicating the need of attention, and requires interruption of the current code the processor is executing. As a response, the processor suspends its current activities, saves its state and executes a particular function to service the event that has caused the interruption. Such function is often called an interrupt handler or an interrupt service routine. Once the processor has responded to the interrupt, i.e. after the processor has executed the interrupt handler, the processor resumes its previously saved state and resumes the execution of the same program it was executing before the interrupt occurred. The interrupts are often caused by external devices that communicate with the processor (Interrupt-driven I/O). Whenever these devices require the processor to execute a particular task, they generate interrupts and wait until the processor has acknowledged that the task has been performed. -

Operating System Review

COP 4225 Advanced Unix Programming Operating System Review Chi Zhang [email protected] 1 About the Course zPrerequisite: COP 4610 zConcepts and Principles zProgramming {System Calls zAdvanced Topics {Internals, Structures, Details {Unix / Linux 2 What is an Operating System? zA general purpose software that acts as an intermediary between users of a computer and the computer hardware. {Encapsulates hardware details. {Controls and coordinates the use of the hardware among the various application programs for the various users. zUse the computer hardware in an efficient manner. 3 Abstract View of O.S. 4 OS Features Needed for Multiprogramming zCPU scheduling – the system must choose among several jobs ready to run. zMemory management – the system must allocate the memory to several jobs. zI/O routine supplied by the system. zAllocation of devices (e.g. Disk usage). 5 Parallel Systems zMultiprocessor systems with more than one CPU in close communication. zTightly coupled system – processors share memory and a clock; communication usually takes place through the shared memory. zAdvantages of parallel system: {Increased throughput {Economical {Increased reliability 6 Parallel Systems (Cont.) z Symmetric multiprocessing (SMP) {Each processor runs an identical copy of the operating system. {Many processes can run at once without performance deterioration. {Most modern operating systems support SMP 7 Computer-System Architecture 8 Computer-System Operation z I/O devices and the CPU can execute concurrently, competing for memory accesses. {Memory controller synchronizes accesses. z Each device controller has a local buffer. z CPU moves data between main memory and local buffers of controllers. z I/O is from the device to local buffer of controller. -

NVIC for Kinetis K Series Mcus | Training

Hello, and welcome to this presentation of the Nested Vector Interrupt Controller – or NVIC – module for Kinetis K series MCUs. In this session, you’ll learn about the NVIC, its main features and the application benefits of leveraging this function. 0 In this presentation, we’ll cover: • An overview of the NVIC module itself • The on-chip interconnections and inter-module dependencies • Software configuration • And some frequently asked questions 1 Let’s first begin with an overview of the module. 2 NVIC Module Features and Application Benefits Features •The NVIC module is located within the ARM® Cortex®-M4 core and provides low latency interrupt servicing by taking only 12 clock cycles to start or exit the interrupt service routine, or ISR. In case there are two pending interrupts, it will take 6 clock cycles • There are up to 120 interrupt sources on the NVIC implementation for Kinetis devices. The first 16 interrupt sources are dedicated to the ARM Cortex-M4 core • The NVIC module supports up to 16 interrupt priority levels for peripherals. However, the priority level for the ARM Cortex-M4 core exceptions are fixed Application benefits, include: • Automatic nested interrupt support is provided for embedded systems, so low priority interrupt requests are delayed when high priority requests are pending • The vector table can be relocated from Flash to RAM for applications such as bootloaders 3 Exception Stacking Exceptions are the interrupts that come from the core. Kinetis K MCUs are based on ARM® Cortex®-M4 cores. When an exception is triggered, the ARM Cortex-M4 processor will start the exception process where 8 registers are pushed onto the stack before fetching the ISR address. -

Interrupt Handling

,ch10.10847 Page 258 Friday, January 21, 2005 10:54 AM CHAPTER 10 Chapter 10 Interrupt Handling Although some devices can be controlled using nothing but their I/O regions, most real devices are a bit more complicated than that. Devices have to deal with the external world, which often includes things such as spinning disks, moving tape, wires to distant places, and so on. Much has to be done in a time frame that is differ- ent from, and far slower than, that of the processor. Since it is almost always undesir- able to have the processor wait on external events, there must be a way for a device to let the processor know when something has happened. That way, of course, is interrupts. An interrupt is simply a signal that the hardware can send when it wants the processor’s attention. Linux handles interrupts in much the same way that it handles signals in user space. For the most part, a driver need only register a handler for its device’s interrupts, and handle them properly when they arrive. Of course, underneath that simple picture there is some complexity; in particular, interrupt handlers are somewhat limited in the actions they can perform as a result of how they are run. It is difficult to demonstrate the use of interrupts without a real hardware device to generate them. Thus, the sample code used in this chapter works with the parallel port. Such ports are starting to become scarce on modern hardware, but, with luck, most people are still able to get their hands on a system with an available port. -

Interrupt and System Call in Linux Today

Interrupt and System Call in Linux Today Interrupts in Linux System calls in Linux Monolithic kernel All OS components run in kernel mode User mode APP Kernel mode FS Mem Net Why good? ▪ Can be efficient. Cross-component access cheap Why bad? ▪ No boundaries Big, complex kernel hard to change • Hard to do new stuff in OS OS researchers unhappy • No flexibility for apps. Hard to customize for speed (web server) ▪ Trusted computing base (TCB) large, one error entire kernel crash, or be compromised Virtual Machine Virtual Machine Monitor (VMM): kernel that provides hardware interface APP APP APP User mode OS OS OS Kernel mode VMM Why good? ▪ Isolation. Strong protection between VMs ▪ Consolidation. One physical machine, multiple VMs ▪ Mobility. Can move VMs around ▪ Standardization: same hw better system mgmt Virtual Machine (cont) Normal operating system environment: ▪ running in supervisor mode ▪ full access to machine state and I/O devices Virtualized guest operating systems: ▪ running in user mode ▪ no direct access to machine state Tasks of the virtual machine monitor: ▪ reconciling the virtual and physical architecture ▪ preventing virtual machines from interfering with each other or the monitor ▪ Do it fast? Not a easy job … Linux kernel structure Core + dynamically loadable modules Modules include: device drivers, file systems, network protocols, etc Modules were originally developed to support the conditional inclusion of device drivers ▪ Early OS kernels would need to either: • include code for all possible devices -

Mid-Review LC3 Basics, -- Architecture, ISA -- I/O Programming

Mid-Review LC3 basics, -- architecture, ISA -- I/O programming -- polling -- interrupt/exception basics state+restart, OS entry, context switch -- C+Assembly -- basic translation (if-then, while, variable access) -- call frames, local variables, arguments, return values, return addresses -- Calling .asm from C -- passing args -- returning values -- C-callable wrappers for TRAP routines -- OS service structure -- low-level services, higher-level services -- interrupt/request service pairs -- Linking -- object files, headers, symbol tables -- relocation, libraries -- static versus dynamic linking -- memory maps, global data, function pointers, pointer variables -- Performance -- Measures -- avg, best, worst, actual cases -- latency, throughput, response -- Time, wall clock, OS+user, user cpu -- Energy/power -- Basic performance equation -- Speedup -- Amdahl's law Performance (continued) -- Benchmarks -- averaging performance (speedup comparisons, GM) -- absolute performance comparisons (speedup) -- job mix/size dependency -- Instruction counts -- tracing -- averaging CPI by classes Parallelism Principles -- Pipelining -- cut set principle -- register setup time, clock skew -- CR speedup -- Interleaving -- hiding latencies -- banking, duplication -- Redundancy -- Common case -- Duplication -- heterogenous, multiple different units -- Fault Tolerance -- Error correction (codes, duplicated functional units) -- Duplication for faulty unit replacement Costs -- Chip cost curves w/ time -- Silicon -- wafers, dice, testing, yield -- fixed cost overhead,