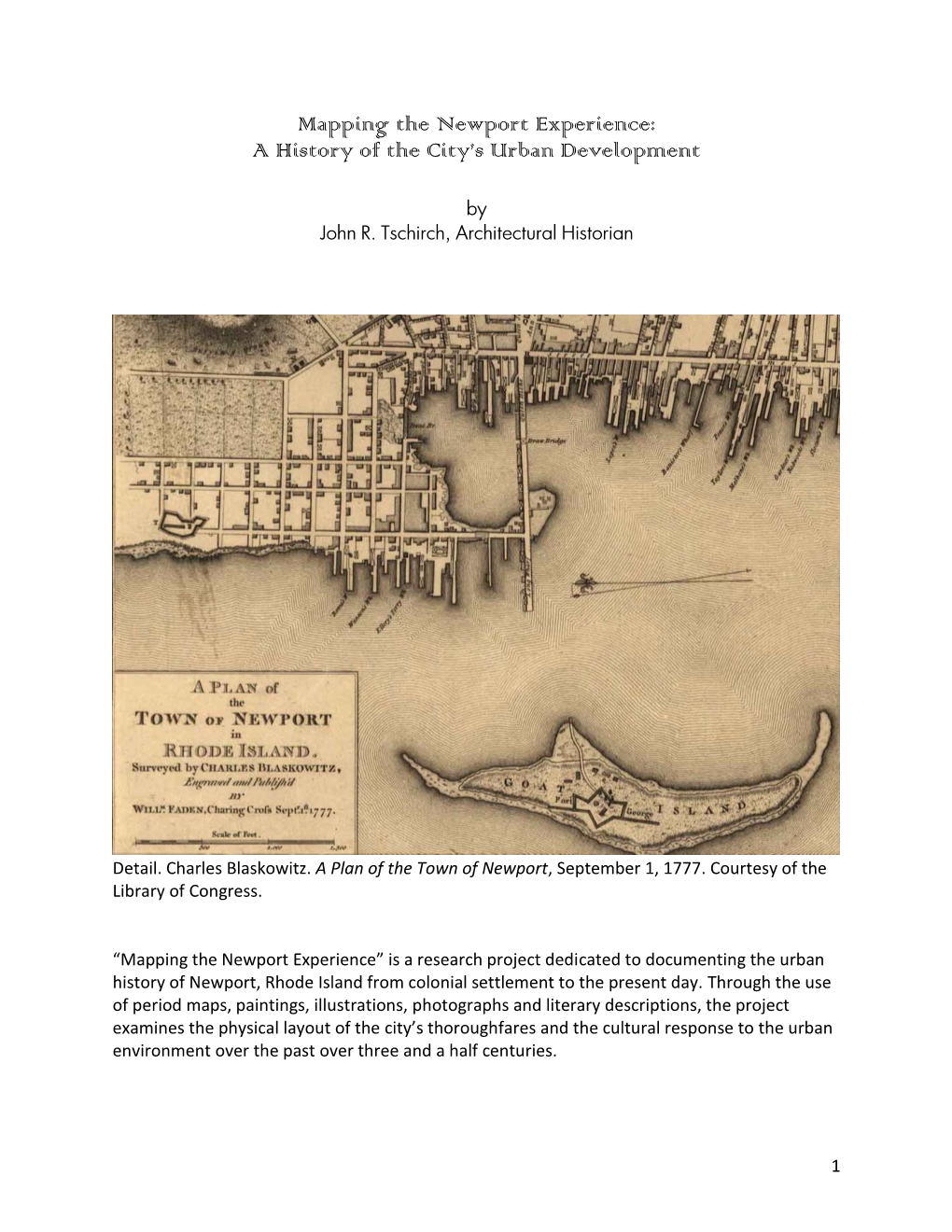

Mapping the Newport Experience: a History of the City's Urban Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Once Called America's Versailles, Newport, Rhode Island's Charm Still

Once called America’s Versailles, Newport, Rhode Island’s charm still lies in its National Registered Historic Landmark District. It is a seaside city on Aquidneck Island, 37 miles southeast of Providence, Rhode Island. The population of Newport is approximately 25,000. Newport gives a picture of America’s Gilded Age with palatial mansions where the rich built summer homes that were more like hotels. The Breakers, Elms, Rosecliff and Marble House are on most tourists’ agendas when in the area. Other sites to see are Rose Island Lighthouse, Rough Point, Cliff Walk and Newport’s Rocky Coastline. When it comes to historic preservation, Doris Duke is remembered by locals with much admiration. Born in 1912, Ms. Duke was the daughter of an American tobacco tycoon. Her philanthropic interests were as varied as her world travels, social life and interest in the arts. Until her death in 1992, Doris Duke was a major player in preserving more than 80 historic buildings in Newport. Today the Duke Charitable Foundation still exists and sponsors many social and health concerns. Newport was one of the earliest settlements in Rhode Island, along with Providence and Portsmouth. Newport was founded in 1639. It began as a beacon for religious tolerance and political freedom. People who had been persecuted in Europe heard of Newport’s acceptance and came to live and work there. An important seaport town during the 18th century, Newport played an important part in what was known as the Triangle Trade (1739‐1760). From sugar and molasses converted to rum and shipped to Africa for slaves, fortunes were made by those in that business. -

Family Law Section Chair Mitchell Y

NEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION Family Law Section Chair Mitchell Y. Cohen, Esq. Johnson & Cohen LLP White Plains Program Co-Chairs Rosalia Baiamonte, Esq. Gassman Baiamonte Gruner, P.C. Garden City NYSBA Dylan S. Mitchell, Esq. Blank Rome LLP New York City Family Law Section Peter R. Stambleck, Esq. Aronson Mayefsky & Sloan, LLP Summer Meeting New York City Family Law Section The Newport Marriott Hotel CLE Committee Co-Chairs Rosalia Baiamonte, Esq. 25 Americas Cup Ave. Gassman Baiamonte Gruner, PC Garden City Newport, RI Henry S. Berman, Esq. Berman Frucco Gouz Mitchel & Schub PC July 13–16, 2017 White Plains Charles P. Inclima, Esq. Inclima Law Firm, PLLC Rochester Peter R. Stambleck, Esq. Aronson Mayefsky & Sloan, LLP New York City Under New York’s MCLE rule, this program may qualify for UP Bruce J. Wagner, Esq. TO 6.5 MCLE credits hours in Areas of Professional Practice. This McNamee, Lochner, Titus & program is not transitional and is not suitable for MCLE credit for Williams, P.C. newly-admitted attorneys. Albany SCHEDULE OF EVENTS Thursday, July 13 9:00 a.m. – 10:30 a.m. Officers Meeting 12:00 p.m. Registration and Exhibits — South Foyer 2:00 p.m. – 4:30 p.m. Executive Committee Meeting — Salons II, III, IV 6:00 p.m. – 10:00 p.m. Kid’s Dinner & Activities — Portsmouth Room 6:15 p.m. Shuttle will leave for the reception/dinner at the Newport Yachting Center (Bohlin); The shuttle will run a continuous loop 6:30 p.m. – 9:30 p.m. Reception and lobster bake at the Newport Yachting Center (Bohlin) Friday, July 14 7:30 a.m. -

La::I'nid Dark Blue Eyes More Ten!:Rnou

was for his rec- Lynch congratulated Mr. Robert Harding, is chosen assis- satisfaction to the utmost shall be a- He reverenced inflexible himself not ouly pitulity was learned by all with sorrow MEMOIR OF R. ISLAND titude, and loved for Lis escension on the second son which God had sent and indignation. tant for a whole year, or tiila new be warded. 7 i and mildness. But on the %1640. The importations of settlers Tt is ordered, that book shall yet m:mde—- him,but beneficial influence which ‘A dagger blood, had been chosen. 14th. a the idol of the citizens fair the unvarying gentleness of steeped in to transporta- and their the amiable found by the now ceased. The motive assis- be provided wherein the Secretary wifes—wag his son, according to the youthwouldhave on darker and velvet cap of the Epaniard Mr. William Balston, is chosen Edward’s not far from it a hat tion to America was over by the change write all such laws and acts as are made chronicle, pne of the most distinguished vehement character.—This hope appear- and ornamt«i tant and Treasurer for a whole year or lbulll with plumes and a clasp of gems, ‘show- then ofhis time. To perfect man- ed likely of affairs of England, they who and constituted by the body to be left al- oung men to be completely fulfilled. Ed- ed the recent traces of who tilla new be chosen. 1 ‘{y beauty and the most noble air, he ward who found a man seem- to give the best account say ways that town where the said all in Gomez that was ed to have safety professed Mr. -

A Matter of Truth

A MATTER OF TRUTH The Struggle for African Heritage & Indigenous People Equal Rights in Providence, Rhode Island (1620-2020) Cover images: African Mariner, oil on canvass. courtesy of Christian McBurney Collection. American Indian (Ninigret), portrait, oil on canvas by Charles Osgood, 1837-1838, courtesy of Massachusetts Historical Society Title page images: Thomas Howland by John Blanchard. 1895, courtesy of Rhode Island Historical Society Christiana Carteaux Bannister, painted by her husband, Edward Mitchell Bannister. From the Rhode Island School of Design collection. © 2021 Rhode Island Black Heritage Society & 1696 Heritage Group Designed by 1696 Heritage Group For information about Rhode Island Black Heritage Society, please write to: Rhode Island Black Heritage Society PO Box 4238, Middletown, RI 02842 RIBlackHeritage.org Printed in the United States of America. A MATTER OF TRUTH The Struggle For African Heritage & Indigenous People Equal Rights in Providence, Rhode Island (1620-2020) The examination and documentation of the role of the City of Providence and State of Rhode Island in supporting a “Separate and Unequal” existence for African heritage, Indigenous, and people of color. This work was developed with the Mayor’s African American Ambassador Group, which meets weekly and serves as a direct line of communication between the community and the Administration. What originally began with faith leaders as a means to ensure equitable access to COVID-19-related care and resources has since expanded, establishing subcommittees focused on recommending strategies to increase equity citywide. By the Rhode Island Black Heritage Society and 1696 Heritage Group Research and writing - Keith W. Stokes and Theresa Guzmán Stokes Editor - W. -

The President's Desk: a Resource Guide for Teachers, Grades 4

The President’s Desk A Resource Guide for Teachers: Grades 4-12 Department of Education and Public Programs With generous support from: Edward J. Hoff and Kathleen O’Connell, Shari E. Redstone John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum Table of Contents Overview of The President’s Desk Interactive Exhibit.... 2 Lesson Plans and Activities................................................................ 40 History of the HMS Resolute Desk............................................... 4 List of Lessons and Activities available on the Library’s Website... 41 The Road to the White House...................................................................... 44 .......................... 8 The President’s Desk Website Organization The President at Work.................................................................................... 53 The President’s Desk The President’s Desk Primary Sources.................................... 10 Sail the Victura Activity Sheet....................................................................... 58 A Resource Guide for Teachers: Grades 4-12 Telephone.................................................................................................... 11 Integrating Ole Miss....................................................................................... 60 White House Diary.................................................................................. 12 The 1960 Campaign: John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Scrimshaw.................................................................................................. -

State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations at the End of The

TUB PBBlOD 01' THE FIBST CHARTER, 1648-63. 80 Although there is not space here to allude in detail to the provisions of this code, the remarks of Judge Staples on the subject, written over fifty years ago, should certainly be quoted. These early legislators, he says, c, began at the foundation, and adopted a bill of rights which secured all that their ancestors had wrested from their kings, and which their countrymen had subsequently lost, and were then endeav oring to regain. They clothe them in language too plain not to be understood. They were a simple people, and the language of their laws was such 88 a people would naturally use. They regarded them selves, within the scope of their charter, as the only source of power among them, and they in practice declared 'that their government derived all its just powers from the consent of the governed'. They expressly declared their government to be a democracy, or Cgovern ment held by the consent of all the free inhabitants'. This declaration was 88 heterodox in the political systems of that day, as were their notions of soul-liberty. ... Tbis code, and the acts and orders p88lled at its adoption, constituted the fundamentallaw8 of the colony while the charter remained in force. The alterations made in them during that period were rather formal than substantial. Their spirit remained unchanged, and has been infused into all the subsequent legislation of the colony and state".! CHAPTER VII. THE PERIOD OF THE FIRST CHARTER, 1648-68. The people of Rhode Island had started the-machinery of their new framework of government, but they were poorly qualified to keep the machine running smoothly and easily. -

Builders' Rule Books Published in America

Annotated Bibliography of Builders' Rule Books Published in America Note: Content for this bibliography was originally developed in the 1970s. This version of the bibliography incorporates some preliminary edits to update information on the archives involved and the location of some of the rule books. HPEF intends to continue to update the information contained in the bibliography over time. If you have corrections or information to add to the bibliography, please contact: [email protected] Elizabeth H. Temkin Summer Intern - 1975, 1976 National Park Service Washington, DC Library Information American Antiquarian Society 185 Salisbury St. Worcester, MA 01609 American Institute of Architects National Office 1735 New York Ave., NW Washington, DC Avery Library Columbia University New York, NY Baker Library Harvard University School of Business Soldiers Field Road Boston, MA Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library Yale University New Haven, CT Boston Athenaeum 10-1/2 Beacon St. Boston, MA Boston Public Library 666 Boylston St. Boston, MA John Carter Brown Library Brown University Providence, RI Essex Institute l32A Essex St. Salem, MA Bostonian Society Old State House 206 Washington St. Boston, MA Carpenters’ Company of the City and County of Philadelphia Carpenters' Hall Philadelphia, PA Chester County Historical Society 225 North High Street West Chester, PA 19380-2658 University of Cincinnati Library University of Cincinnati Cincinnati, OH Free Library of Philadelphia Logan Square Philadelphia, PA Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Museum San Marino, CA University of Illinois Architecture Library Arch Building University of Illinois Urbana. IL Indiana Historical Society 140 N. Senate Ave. Indianapolis, IN Indiana State Library Indiana Division 140 N. -

Aquidneck Island's Reluctant Revolutionaries, 16'\8- I 660

Rhode Island History Pubhshed by Th e Rhod e bland Hrstoncal Society, 110 Benevolent St reet, Volume 44, Number I 1985 Providence, Rhode Island, 0 1~, and February prmted by a grant from th e Stale of Rhode Island and Providence Plamauons Contents Issued Ouanerl y at Providence, Rhode Island, ~bruary, May, Au~m , and Freedom of Religion in Rhode Island : November. Secoed class poet age paId al Prcvrdence, Rhode Island Aquidneck Island's Reluctant Revolutionaries, 16'\8- I 660 Kafl Encson , presIdent S HEI LA L. S KEMP Alden M. Anderson, VIet presIdent Mrs Edwin G FI!I.chel, vtce preudenr M . Rachtl Cunha, seatrory From Watt to Allen to Corliss: Stephen Wllhams. treasurer Arnold Friedman, Q.u ur<lnt secretary One Hundred Years of Letting Off Steam n u ow\ O f THl ~n TY 19 Catl Bndenbaugh C H AR LES H O F f M A N N AND TESS HOFFMANN Sydney V James Am cmeree f . Dowrun,; Richard K Showman Book Reviews 28 I'UIIU CAT!O~ S COM!I4lTT l l Leonard I. Levm, chairmen Henry L. P. Beckwith, II. loc i Cohen NOl1lUn flerlOlJ: Raben Allen Greene Pamtla Kennedy Alan Simpson William McKenzIe Woodward STAff Glenn Warren LaFamasie, ed itor (on leave ] Ionathan Srsk, vUlI1ng edltot Maureen Taylo r, tncusre I'drlOt Leonard I. Levin, copy editor [can LeGwin , designer Barbara M. Passman, ednonat Q8.lislant The Rhode Island Hrsto rrcal Socrerv assumes no respcnsrbihrv for the opinions 01 ccntnbutors . Cl l9 8 j by The Rhode Island Hrstcncal Society Thi s late nmeteensh-centurv illustration presents a romanticized image of Anne Hutchinson 's mal during the AntJnomian controversy. -

Organization Lloyd Albert AAA Northeast Thomas Ardito

First Name: Last Name: Organization Lloyd Albert AAA Northeast Thomas Ardito Aquidneck Island Planning Commission William Ashworth VHB Kate Aubin Lisa Aurecchia Woonasquatucket River Watershed Council Scott Avedisian City of Warwick Robert Azar Providence Planning & Development Paul Bannon BETA Group, Inc. Anthony Baro E2SOL LLC Dan Baudouin The Providence Foundation Ingrid Bentsen Matthew Blair Annette Bourne Grow Smart RI Laura Bozzi Karen Bradbury Office of Senator Sheldon Whitehouse Meredith Brady Rhode Island Department of Transportation Peter Brassard Todd Brayton Bryant Associates, Inc. Brett Broesder Edward Brown RIPTA James Brown Bryant University Kenneth Burke RI Water Resources Board Liza Burkin Bike Newport Linsey Callaghan Rhode Island Statewide Planning Program Allison Callahan Rhode Island Deparment of Environmental Management Chris Capizzo Shechtman Halperin Savage, LLP Lauren Carson State Representative Taber Caton Searle Design Group Josh Catone James Celenza RICOSH Buff Chace Cornish Associates, LP Nathaniel Chace Cornish Associates, LP Sandra Clarey McMahon Associates Molly Clark American Lung Association in Rhode Island Abel Collins Coalition for Transportation Choices Dylan Conley Millennial Professional Group of Rhode Island Sam Coren Ellen Cynar City of Providence- Healthy Communities Jeff Davis Rhode Island Division of Planning Stephen Devine RIDOT Alberta Devor James Diossa City of Central Falls Steve Durkee Cornish Assoc. Arthur Eddy Birchwood Design Group Jerry Elmer Conservation Law Foundation Jim Eng Rhode -

Map of 359 Thames Street - Northeast & Downtown Newport, RI

Map of 359 Thames Street - Northeast & Downtown Newport, RI Scenic DOWNTOWN NEWPORT POINTS OF INTEREST 1 Hunter1 House Perrotti Park / Newport Harbor Shuttle / Block Island Ferry / 2 Water Taxi Rose Island 3 The Museum of Newport History Light House Trinity Church / Queen Anne Square / 4 Installation: The Meeting Room by Maya Lin 5 Seamen’s Church Institute 6 Bannister’s and Bowen’s Wharf/Jamestown Ferry Newport Visitor 7 Samuel Whitehorne House Museum Information & Transportation Center 8 International Yacht Restoration School 9 King Park Goat Island Newport Light House Train Depot 10 Fort Adams State Park / Sail Newport Cardines Field Historic Fort Adams / Museum of Yachting / Sail Newport 11 Waterfront Center 12 Eisenhower House Newport 13 Newport Public Library Shipyard 14 St. Mary’s Church Easton’s Beach / Newport Exploration Center Newport 15 Yacht Club Perrotti Park 16 Newport Artillery Company 17 Washington Square / Old Colony House Newport Harbor Shuttle 18 Touro Synagogue / Loeb Visitor Center/ Newport Historical Society 19 Redwood Library / Old Stone Mill / Newport Art Museum y 20 International Tennis Hall of Fame and Museum / Casino Theater r r e y F r r 21 Kingscote d e n F a l s n I 22 Isaac Bell House w k o t c s o e Touro 23 The Elms l Park B m a 24 The Breakers Stable J 25 Chateau-sur-Mer 26 National Museum of American Illustration 27 28 Marble House Parking for 3 cars is included with your stay in the underground parking garage 29 Rough Point located at the intersection of Thames Street & Gidley Street 30 The Breakers (To access the parking garage you must 31 Salve Regina University, Ochre Court use Thames Street. -

Bulletin of the Essex Institute, Vol

i m a BULLETIN OF THE ESSEX IlsTSTITUTE]. Vol. 18. Salem: Jan., Feb., Mar., 1886. Kos. 1-3. MR. TOPPAN'S NEW PROCESS FOR SCOURING WOOL. JOHN RITCHIE, JR. Read before the Essex Institute, March 15, 1886, Ladies and Gentlemen^ — Two years ago, almost to a day, I had the pleasure of discussing before you what was at that time a new process of bleaching cotton and cotton fabrics, — process which, since that day, has been developed with steadily increasing value by a company doing business under Mr. Top- pan's inventions. This evening [March 15] I desire your attention to a consideration of the effects of the same solvent principle upon that other great textile material, wool. The lecture of two years ago was illustrated by the pro- cesses themselves, practically performed before your eyes. It is our intention this evening to follow out the same plan and to illustrate and, so far as may be, prove by experiment the statements which shall be made. It is our intention to scour upon the platform various speci- mens of wool, and as well, to dye before you such colors as can be fixed within a time which shall not demand, upon your part, too much of that virtue, patient waiting. Mr. Toppan, who needs no introduction to this audience, will undertake, later in the evening, the scouring of wool, and Mr. Frank Sherry, of Franklin, has kindly offered to assist in the work of dyeing. To those of you who are not familiar with the authorities in this country, in the work of dyeing, I need only say, that Mr. -

Analysis and Evaluation of the Spatial Structure of Cittaslow Towns on the Example of Selected Regions in Central Italy and North-Eastern Poland

land Article Analysis and Evaluation of the Spatial Structure of Cittaslow Towns on the Example of Selected Regions in Central Italy and North-Eastern Poland Marek Zagroba , Katarzyna Pawlewicz and Adam Senetra * Department of Socio-Economic Geography, Faculty of Geoengineering, University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn, Prawoche´nskiego15, 10-720 Olsztyn, Poland; [email protected] (M.Z.); [email protected] (K.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-89-5234948 Abstract: Cittaslow International promotes harmonious development of small towns based on sustainable relationships between economic growth, protection of local traditions, cultural heritage and the environment, and an improvement in the quality of local life. The aim of this study was to analyze and evaluate the differences and similarities in the spatial structure of Cittaslow towns in the Italian regions of Tuscany and Umbria and the Polish region of Warmia and Mazury. The study examined historical towns which are situated in different parts of Europe and have evolved in different cultural and natural environments. The presented research attempts to determine whether the spatial structure of historical towns established in different European regions promotes the dissemination of the Cittaslow philosophy and the adoption of sustainable development principles. The urban design, architectural features and the composition of urban and architectural factors which Citation: Zagroba, M.; are largely responsible for perceptions of multi-dimensional space were evaluated. These goals were Pawlewicz, K.; Senetra, A. Analysis achieved with the use of a self-designed research method which supported a subjective evaluation and Evaluation of the Spatial of spatial structure defined by historical urban planning and architectural solutions.