ORCHARD BEACH: the BRONX RIVIERA Wayne Lawrence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Departmentof Parks

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE DEPARTMENTOF PARKS BOROUGH OF THE BRONX CITY OF NEW YORK JOSEPH P. HENNESSY, Commissioner HERALD SQUARE PRESS NEW YORK DEPARTMENT OF PARKS BOROUGH OF 'I'HE BRONX January 30, 1922. Hon. John F. Hylan, Mayor, City of New York. Sir : I submit herewith annual report of the Department of Parks, Borough of The Bronx, for 1921. Respect fully, ANNUAL REPORT-1921 In submitting to your Honor the report of the operations of this depart- ment for 1921, the last year of the first term of your administration, it will . not be out of place to review or refer briefly to some of the most important things accomplished by this department, or that this department was asso- ciated with during the past 4 years. The very first problem presented involved matters connected with the appropriation for temporary use to the Navy Department of 225 acres in Pelham Bay Park for a Naval Station for war purposes, in addition to the 235 acres for which a permit was given late in 1917. A total of 481 one- story buildings of various kinds were erected during 1918, equipped with heating and lighting systems. This camp contained at one time as many as 20,000 men, who came and went constantly. AH roads leading to the camp were park roads and in view of the heavy trucking had to be constantly under inspection and repair. The Navy De- partment took over the pedestrian walk from City Island Bridge to City Island Road, but constructed another cement walk 12 feet wide and 5,500 feet long, at the request of this department, at an expenditure of $20,000. -

Fresh Kills Dumped : a Policy Assessment for the Management of New York City's Residential Solid Waste in the Twenty-First Century

New Jersey Institute of Technology Digital Commons @ NJIT Theses Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-31-2003 Fresh kills dumped : a policy assessment for the management of New York City's residential solid waste in the twenty-first century Aaron William Comrov New Jersey Institute of Technology Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.njit.edu/theses Part of the Sustainability Commons Recommended Citation Comrov, Aaron William, "Fresh kills dumped : a policy assessment for the management of New York City's residential solid waste in the twenty-first century" (2003). Theses. 615. https://digitalcommons.njit.edu/theses/615 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at Digital Commons @ NJIT. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ NJIT. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright Warning & Restrictions The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a, user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use” that user may be liable for copyright infringement, This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. -

To Download Three Wonder Walks

Three Wonder Walks (After the High Line) Featuring Walking Routes, Collections and Notes by Matthew Jensen Three Wonder Walks (After the High Line) The High Line has proven that you can create a des- tination around the act of walking. The park provides a museum-like setting where plants and flowers are intensely celebrated. Walking on the High Line is part of a memorable adventure for so many visitors to New York City. It is not, however, a place where you can wander: you can go forward and back, enter and exit, sit and stand (off to the side). Almost everything within view is carefully planned and immaculately cultivated. The only exception to that rule is in the Western Rail Yards section, or “W.R.Y.” for short, where two stretch- es of “original” green remain steadfast holdouts. It is here—along rusty tracks running over rotting wooden railroad ties, braced by white marble riprap—where a persistent growth of naturally occurring flora can be found. Wild cherry, various types of apple, tiny junipers, bittersweet, Queen Anne’s lace, goldenrod, mullein, Indian hemp, and dozens of wildflowers, grasses, and mosses have all made a home for them- selves. I believe they have squatters’ rights and should be allowed to stay. Their persistence created a green corridor out of an abandoned railway in the first place. I find the terrain intensely familiar and repre- sentative of the kinds of landscapes that can be found when wandering down footpaths that start where streets and sidewalks end. This guide presents three similarly wild landscapes at the beautiful fringes of New York City: places with big skies, ocean views, abun- dant nature, many footpaths, and colorful histories. -

2006 - 2007 Report Front Cover: Children Enjoying a Summer Day at Sachkerah Woods Playground in Van Cortlandt Park, Bronx

City of New York Parks & Recreation 2006 - 2007 Report Front cover: Children enjoying a summer day at Sachkerah Woods Playground in Van Cortlandt Park, Bronx. Back cover: A sunflower grows along the High Line in Manhattan. City of New York Parks & Recreation 1 Daffodils Named by Mayor Bloomberg as the offi cial fl ower of New York City s the steward of 14 percent of New York City’s land, the Department of Parks & Recreation builds and maintains clean, safe and accessible parks, and programs them with recreational, cultural and educational Aactivities for people of all ages. Through its work, Parks & Recreation enriches the lives of New Yorkers with per- sonal, health and economic benefi ts. We promote physical and emotional well- being, providing venues for fi tness, peaceful respite and making new friends. Our recreation programs and facilities help combat the growing rates of obesity, dia- betes and high blood pressure. The trees under our care reduce air pollutants, creating more breathable air for all New Yorkers. Parks also help communities by boosting property values, increasing tourism and generating revenue. This Biennial Report covers the major initiatives we pursued in 2006 and 2007 and, thanks to Mayor Bloomberg’s visionary PlaNYC, it provides a glimpse of an even greener future. 2 Dear Friends, Great cities deserve great parks and as New York City continues its role as one of the capitals of the world, we are pleased to report that its parks are growing and thriving. We are in the largest period of park expansion since the 1930s. Across the city, we are building at an unprecedented scale by transforming spaces that were former landfi lls, vacant buildings and abandoned lots into vibrant destinations for active recreation. -

Reading the Landscape: Citywide Social Assessment of New York City Parks and Natural Areas in 2013-2014

Reading the Landscape: Citywide Social Assessment of New York City Parks and Natural Areas in 2013-2014 Social Assessment White Paper No. 2 March 2016 Prepared by: D. S. Novem Auyeung Lindsay K. Campbell Michelle L. Johnson Nancy F. Sonti Erika S. Svendsen Table of Contents Acknowledgments .......................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 8 Study Area ...................................................................................................................................... 9 Methods ....................................................................................................................................... 12 Data Collection .................................................................................................................................... 12 Data Analysis........................................................................................................................................ 15 Findings ........................................................................................................................................ 16 Park Profiles ........................................................................................................................................ -

Raising the Tide: Strategies for New York City Beaches

Summer 2007 SPECIAL REPORT A PARK POLICY PAPER Raising the Tide: Strategies for New York City Beaches New Yorkers for Parks The Arthur Ross Center for Parks and Open Spaces 355 Lexington Avenue, 14th Floor New York, NY 10017 212-838-9410 www.ny4p.org New Yorkers for Parks Staff New Yorkers for Parks Board Executive Director Chair Christian DiPalermo Lynden B. Miller Director of Operations Vice-Chairs Maura Lout Barbara S. Dixon Elizabeth Cooke Levy Director of Planning Karen McDonald Micaéla Birmingham Peter Rothschild Executive Assistant Secretary Sharon Cole Mark Hoenig Director of Government and Community Relations Treasurer Sheelah Feinberg Thomas Patrick Dore, Jr. Community Design Program Manager Luis Garden Acosta Pamela Governale Elaine Allen Dana Beth Ardi Development Associate Martin S. Begun Ben Gwynne Michael Bierut Dr. Roscoe Brown, Jr. Director of Research Ann L. Buttenwieser Cheryl Huber Harold Buttrick Ellen Chesler Government and Community Relations Associate William D. Cohan Okenfe Lebarty Audrey Feuerstein Richard Gilder Director of Finance Catherine Morrison Golden Sam Mei Michael Grobstein George J. Grumbach, Jr. Development and Marketing Director Marian S. Heiskell Jennifer Merschdorf Evelyn H. Lauder Karen J. Lauder David J. Loo Thomas L. McMahon This report was prepared by the Danny Meyer Research Department of New Yorkers for Parks. Ira M. Millstein Jennifer M. Ortega Lead Author and Series Director: Cheryl Huber Cesar A. Perales Research Interns: Rachel Berkson, Joanna Reynolds, Jordan Smith, Kaity Tsui Philip R. Pitruzzello Maps: Micaéla Birmingham, Reza Tehranifar Arthur Ross Graphic Design: Monkeys with Crayons Designs A. J. C. Smith Source of maps: NYC Department of Parks and Recreation, 2004. -

Annual Report for Fiscal Year 2014

ANNUAL REPORT 2014 1 61626_NYC_Annual.indd 1 12/11/14 9:55 AM New York City Audubon works to protect wild birds and their habitats in the five boroughs of New York City, improving the quality of life for all New Yorkers. We are an independent nonprofit with 10,000 members, donors, and volunteers whose dedication and support make our research, advocacy, and education work possible. NYC Audubon is affiliated with the National Audubon Society, and provides local services to its members. NYC Audubon is tax-exempt under section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Donations are deductible to the extent allowed by law. NYC Audubon meets all of the Better Business Bureau’s Standards of Charity Accountability. OFFICerS, BoarD OF DIreCtorS, ADVISory CounCIl, anD StaFF President Seasonal Staff, Interns, Harrison D. Maas Trips & Classes Leaders Marielle Anzelone CREATING PARTNERSHIPS TO Executive Vice President Jarad Astin David Speiser Kate Biller Anita Cabrera PROTECT OUR BIRDS Vice President Elizabeth Craig Richard T. Andrias Phil Cusimano Melanie del Rosario ew York City Audubon, the principal voice for New York City’s birds and Treasurer Jennifer Dilone John Shemilt Henry Fandel their habitats, pursues its mission by means of three fundamental tools: Dennis Galcik Secretary Joe Giunta science-based conservation, educational outreach, and advocacy. We speak, Marsilia A. Boyle Clifford Hagen N Bridget Holmes and fight, for the City’s birds. Substantial accomplishments this past year have been Immediate Past President Liz Johnson Oakes Ames Stephen Karkuff empowered by fruitful partnerships—with City agencies, private corporations, fellow Donald Kass environmentalists, and bird enthusiasts—which have allowed us to bring our research Board of Directors Kimiko Kayano Brenda Torres-Barreto1 Paul Keim expertise and rigorously collected field data to bear in offering solutions to the complex Robert Bate2 Darren Klein Clifford Case Jeffrey Kollbrunner challenges facing our urban bird populations. -

Orchard Beach Ultramafic Erratics – Where Are They From?

Orchard Beach Ultramafic Erratics – Where Are They From? C. E. Nehru (Geology Department, Hofstra University, Hempstead, NY 11549; Department of Geology, Brooklyn College, City of University of New York, NY 11210; and Earth and Planetary Sciences Department, American Museum of Natural History, NY 10024), and Charles Merguerian (Geology Department, Hofstra University, Hempstead, NY 11549). Three distinctly different ultramafic erratics are scattered on glacially sculpted and striated bedrock at South Twin Island in Pelham Bay Park, immediately north of Orchard Beach in The Bronx, NYC. We have examined and sampled the three erratics in an attempt to demonstrate provenance and to establish paleoflow patterns of the Pleistocene glacier or glaciers responsible for transporting them. To this end we have conducted field studies, major, minor, trace, and rare-earth element analyses, electron microprobe analyses, and petrographic analysis on the samples and have compared the results to nearby New England ultramafic intrusives found in the published literature. The three samples are evenly distributed within 250 m of each other and we have numbered them from north to south as OB1-N, OB2-C, and OB3-S. OB1-N and OB-2C are most similar in that they are pyroxenites (± olivine) with coarse phaneritic to pegmatitic textures. Sample OB3-S is also a pyroxenite but exhibits an obvious poikilitic texture and is more rounded and slightly more feldspathic by comparison with the other two samples. Our preliminary results indicate that the ultramafic boulders, although similar in major element chemistry and mineralogy are all relatively low in Al2O3 ranging from 4.6% to 9.7% and relatively high in alkalis (especially Na20). -

30 Years of Progress 1934 - 1964

30 YEARS OF PROGRESS 1934 - 1964 DEPARTMENT OF PARKS NEW YORK WORLD'S FAIR REPORT TO THE MAYOR AND THE BOARD OF ESTIMATE ROBERT F. WAGNER, Mayor ABRAHAM D. BEAME, Comptroller PAUL R. SCREVANE, President of the Council EDWARD R. DUDLEY. President. Borough of Manhattan JOSEPH F. PERICONI, President. Borough of The Bronx ABE STARK, President, Borough of Brooklyn MARIO J. CARIELLO, President, Borough of Queens ALBERT V. MANISCALCO, President, Borough of Richmond DEPARTMENT OF PARKS NEWBOLD MORRIS, Commissioner JOHN A. MULCAHY, Executive Officer ALEXANDER WIRIN, Assistant Executive Officer SAMUEL M. WHITE, Director of Maintenance & Operation PAUL DOMBROSKI, Chief Engineer HARRY BENDER, Engineer of Construction ALEXANDER VICTOR, Chief of Design LEWIS N. ANDERSON, JR., Liaison Officer CHARLES H. STARKE, Director of Recreation THOMAS F. BOYLE, Assistant Director of Maintenance & Operation JOHN MAZZARELLA, Borough Director, Manhattan JACK GOODMAN, Borough Director, Brooklyn ELIAS T. BRAGAW, Borough Director, Bronx HAROLD P. McMANUS, Borough Director, Queens HERBERT HARRIS, Borough Director. Richmond COVER: Top, Verrazano-Narrows Bridge Playground Left, New York 1664 Bottom, New York World's Fair 1964-1965 INDEX Page ARTERIALS Parkways and Expressways 57 BEACHES 36 BEAUTIFICATION OF PARKS 50 CONCESSIONS 51 ENGINEERING AND ARCHITECTURAL Design and Construction 41 GIFTS 12 GOLF 69 JAMAICA BAY Wildlife Refuge 8 LAND Reclamation and Landfill 7 MAINTENANCE and OPERATION 77 MARGINAL SEWAGE PROBLEM 80 MUSEUMS AND INSTITUTIONS 71 MONUMENTS 13 PARKS 10 RECREATION Neighborhood, Recreation Centers, Golden Age Centers, Tournaments, Children's Programs, Playgrounds, Special Activi- ties 15 SHEA STADIUM FLUSHING MEADOW 67 SWIMMING POOLS 40 WORLDS FAIR 1964-1965 Post-Fair Plans 56 ZOOS 76 SCALE MODEL OF NEW YORK CITY EXHIBITED IN THE CITY'S BUILDING AT WORLD'S FAIR. -

Yesteryear in the Bronx Yesteryear in the Bronx

CELEBRATING THE EXPERIENCE OF GROWING UP AND LIVING IN THE BRONX YesteryearYesteryear InIn TheThe BronxBronx PostcardsPostcards P. S . 9 5 Augustinian Church of St. Nicholas of Tolentine Fordham Road & University Avenue P. S . 8 1 Bronx Church House Back In THE BRONX ~ Postcards 2 Hall of Fame, surrounding Gould Memorial Library Hall of Fame, Interior Colonnade, l-r, Thedore Roosevelt, Grover Cleveland, James Monroe, Andrew New York University, University Heights, 181st St & University Ave Jackson, James Madison St. Raymond’s Church, Castle Hill & Tremont Ave., Parkchester, view in 1900 Hall of Fame, open colonnade is 250 feet long and 14 feet wido Back In THE BRONX ~ Postcards 3 P.S. 1 P. S . 6 College Avenue, 145th & 146th Streets Tremont, Bryant & Vyse Avenues, West Farms P.S. 4 P. S . 5 Fulton & Third Avenues & 173rd Street Webster Avenue & 189th Street Back In THE BRONX ~ Postcards 4 P.S. 8 P. S . 1 2 Bedford Park Westchester, NY P. S . 1 0 P. S . 1 1 Eagle Avenue & 163rd Street Back In THE BRONX ~ Postcards 5 P. S . 1 3 P. S . 2 5 Park Avenue, 215th & 216th Streets NE corner of Union Avenue & 149th Street P. S . 1 4 P. S . 1 2 Eastern Boulevard, Throgg’s Neck, NY Westchester, NY Back In THE BRONX ~ Postcards 6 P. S . 3 6 P. S . 3 6 Bronx, Unionport, NYC Unionport P. S . 3 6 P. S . 4 0 Union Port, NY Prospect Avenue & Jennings Street, Bronx, NYC Back In THE BRONX ~ Postcards 7 P. S . 3 3 P. S . 3 3 Jerome & Walton Avenues, Bronx, NYC Bronx, NY P. -

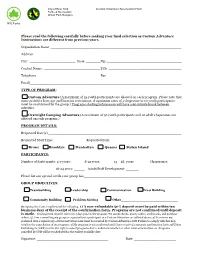

Please Read the Following Carefully Before Making Your Final Selection As Custom Adventure Instructions Are Different from Previous Years

City of New York Custom Adventure Reservation Form Parks & Recreation Urban Park Rangers www.nyc.gov/parks Please read the following carefully before making your final selection as Custom Adventure Instructions are different from previous years. Organization Name _______________________________________________________________ Address _______________________________________________________________________ City: ______________________ State _______ Zip ____________________________________ Contact Name: ___________________________ Title ___________________________________ Telephone ______________________________ Fax ____________________________________ Email _________________________________________________________________________ TYPE OF PROGRAM: Custom Adventure (A maximum of 32 youth participants are allowed on each program. Please note that some activities have age and location restrictions. A minimum ratio of 1 chaperone to 10 youth participants must be maintained by the group.) Programs starting before noon will have a 60 minute break between activities. Overnight Camping Adventure (A maximum of 30 youth participants and 10 adult chaperones are allowed on each program.) PROGRAM DETAILS: Requested Date(s) ________________________________________________________________ Requested Start Time: _______________ Requested Park: _________________________________ Bronx Brooklyn Manhattan Queens Staten Island PARTICIPANTS: Number of Participants: 4-7 years: _____ 8-12 years: _____ 13 – 18: years ______ Chaperones: ______ 18-24 years: _____ Adult/Staff -

Nycparks__Outdoors JAS12 Eblast.Indd

THE FREE NEWSPAPER OF OUTDOOR ADVENTURE JULY / AUGUST / SEPTEMBER 2012 INCLUDES CALENDAR OF URBAN PARK RANGER FREE WEEKEND ADVENTURES 2 NYCParks nyc.gov/parks/rangers URBAN PARK RANGERS What does a real New York City adventure Pond Park. This unique opportunity for Message From: mean to you? For many, it means strolling team-building and individual fun includes through Times Square, necks craned a zip line, a climbing wall, balance Richard Simon upward to drink in the lights and sounds platforms, and a series of low- and high- of Broadway. For others, it’s a day spent ropes courses. As the fi rst challenge Deputy Director cheering for their favorite team at Yankee course in New York City, it fosters Stadium or Citi Field. Yet for some, true necessary life skills like problem solving, Urban Park Rangers adventure can be found exploring the overcoming personal fears, while promoting verdant parkland and natural areas of our leadership and group interaction. At the city. For over thirty years, New York City’s Alley Pond Park Adventure Course, you can Urban Park Rangers have served as the literally climb to new heights of adventure. ambassadors to our emerald empire, providing outdoor adventure programs Heading to the beach this summer? Then that promote physical fi tness, cultural join us for some of our special Weekend awareness, and the exploration of nature. Adventures taking place throughout the Jamaica Bay area of Queens and eastern It’s our mission to connect New Yorkers Brooklyn, which are listed in this edition of to the natural world. Each weekend Outdoors in New York City.