Chicahuaxtla Triqui-Plumed Serpent Redacted Version Revised 05-29

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origin of the Peculiarities of the Vietnamese Alphabet André-Georges Haudricourt

The origin of the peculiarities of the Vietnamese alphabet André-Georges Haudricourt To cite this version: André-Georges Haudricourt. The origin of the peculiarities of the Vietnamese alphabet. Mon-Khmer Studies, 2010, 39, pp.89-104. halshs-00918824v2 HAL Id: halshs-00918824 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00918824v2 Submitted on 17 Dec 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Published in Mon-Khmer Studies 39. 89–104 (2010). The origin of the peculiarities of the Vietnamese alphabet by André-Georges Haudricourt Translated by Alexis Michaud, LACITO-CNRS, France Originally published as: L’origine des particularités de l’alphabet vietnamien, Dân Việt Nam 3:61-68, 1949. Translator’s foreword André-Georges Haudricourt’s contribution to Southeast Asian studies is internationally acknowledged, witness the Haudricourt Festschrift (Suriya, Thomas and Suwilai 1985). However, many of Haudricourt’s works are not yet available to the English-reading public. A volume of the most important papers by André-Georges Haudricourt, translated by an international team of specialists, is currently in preparation. Its aim is to share with the English- speaking academic community Haudricourt’s seminal publications, many of which address issues in Southeast Asian languages, linguistics and social anthropology. -

Teachers Learning Lucha in Oaxaca, Mexico

FIRE: Forum for International Research in Education Vol. 5, Iss. 2, 2019, pp. 6-27 TRAINED TO RESIST: TEACHERS LEARNING LUCHA IN OAXACA, MEXICO Christian Alejandro Bracho1 University of La Verne, USA Abstract Drawing on ethnographic data and interviews with 17 teacher educators and normal school students in Oaxaca, Mexico, this article examines a particular teaching formation rooted in the concept of lucha, revolutionary struggle. Participants described how, during their four years at a normal school, they learn, rehearse, and internalize a historical set of revolutionary scripts and strategies, as part of a political role they will perform as teachers. The post-1968 generation of teachers in this study recalled learning to fight in the 1970s and 80s, in an era of great opposition to the Mexican government and national union, while the younger generation described learning how to advocate for themselves so that they can create change in their communities. The study demonstrates how teacher training can explicitly cultivate new teachers’ capacities to operate as political actors, in opposition to standardized and apolitical professional models. Keywords: teacher training; activism; resistance; Oaxaca; normal schools In 2006, teachers in Oaxaca, Mexico made international headlines when they led a popular rebellion against the local and federal authorities, in opposition to the violent crackdown of a teachers’ strike over the summer. Dozens of teachers and activists were killed, and hundreds were injured over several months of insurrection. In 2014, 43 student teachers from a teacher training college (i.e., a normal school) were kidnapped and massacred while traveling around Guerrero state in an effort to organize funds for a strike in October, one that would commemorate the Tlatelolco Massacre in Mexico City in 1968. -

6 X 10.5 Long Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-51840-6 - An Introduction to Classical Nahuatl Michel Launey Excerpt More information Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī PART Ī Ī ONE Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-51840-6 - An Introduction to Classical Nahuatl Michel Launey Excerpt More information PRELIMINARY LESSON Phonetics and Writing S ince the time of the conquest, Nahuatl has been written by means of theLatinalphabet.Thereis,therefore,alongtraditiontowhichitis preferable to conform for the most part. Nonetheless, for the following reasons, somewordsinthisbookarewritteninanorthographythatdiffersfromthe traditional one. ̈ Theorthographyis,ofcourse,“hispanicized.”Torepresentthephoneticele- ments of Nahuatl, the letters or combinations of letters that represent identical or similar sounds in Spanish are used. Hence, there is no problem with the sounds that exist in both languages, not to mention those that are lacking in Nahuatl (b, d, g, r etc.). On the other hand, those that exist in Nahuatl but not inSpanisharefoundinalternatespellings,orareevenaltogetherignored.In particular, this is the case with vowel length and (even worse) with the glottal stop (see Table 1.1), which are systematically marked only by two grammar- ians, Horacio Carochi and Aldama y Guevara, and in a text named Bancroft Dialogues.1 ̈ This defective character is heightened by a certain fluctuation because the orthography of Nahuatl has never really been fixed. Hence, certain texts represent the vowel /i/ indifferently with i or j, others always represent it with i but extend this spelling to consonantal /y/, that is, to a differ- ent phoneme. -

Saltillo Street Names Index: Autumn Gleen Dr

M R - 6 - E R R - 5 - E C c 1 2 3 D 4 5 6 7 U C S D A T R . E R D L 6 . 8 E 3 Y SNER ST. RD 2446 MES SALTILLO STREET NAMES INDEX: AUTUMN GLEEN DR. E3 OLD HWY. 51 E3 A BAUHAUS DR. E3 OLD NATCHEZ TRACE TRAIL G3 BENT GRASS CIR. H2 OLD SALTILLO RD. E4, F4, F5, G5, H4, H5 A BERCH TREE DR. F4 OLD SOUTH PLANTATION DR. E2 R D BIG HARPE TRAIL G2 OLIVIA CV. D4 BIRMINGHAM RIDGE RD. F1, F2, G3 7 PARKRIDGE DR, F4 8 3 BOLIVAR CIR. G3 PATTERSON CIR. E5 . D BOSTIC AVE. E4 PECAN DR. D5 R BRIDLE CV. E3 PETE AVE. F3 D U BRISCOE ST. E4 PEYTON LN. D4 H BROCK DR. F3 33 35 35 35 PINECREST ST. E4 ST 32 32 33 TOWERY . CARTWRIGHT AVE. E4 PINEHURST AVE. E4 31 36 31 R 4 3 D 3 2 CHAMPIONS CV. H2 PINEWOOD ST. E4 5 6 5 4 CHERRY HILL DR. C4 POPULARWOOD LN. F4 1 6 9 5 CHESTNUT LN. C4 PRINSTON DR. E3 1 CHICKASAW CIR. G3 PULLTIGHT RD. B4, C4 CHICKASAW TRAIL G3 PYLE DR. E4 CHRISTY WAY C4 QUAIL CREEK RD. E3 CO 653-B H2, H3 RAILROAD AVE. E5 CO 653-D G3 RD 189 F3 CO 2012 E2, E3 RD 251 D2 3 CO 2012 F3 8 RD 521 C1, E2 7 CO 2720 A1 RD 599 C1, C2, D2 D R CO 2720 B1 RD 647 H3 COBBS CV. -

Running Head: Structural Violence Against Indigenous Oaxacans: a Transnational 1 Phenomenon

Running head: Structural Violence Against Indigenous Oaxacans: A Transnational 1 Phenomenon Structural Violence Against Indigenous Oaxacans: A Transnational Phenomenon Andrew Tarbox Submission for Social Sciences Structural Violence Against Indigenous Oaxacans: A Transnational Phenomenon 2 Structural violence refers to the “social arrangements that systematically bring subordinated and disadvantaged groups into harm’s way and put them at risk for various forms of suffering” (Benson, 2008, p. 590). In the agricultural labor sector in the United States, structural violence takes the form of “deplorable wages and endemic poverty, forms of stigma and racism, occupational health and safety hazards, poor health” (Benson, 2008, p. 591). This system of structural violence began to develop in the agricultural sector in the nineteenth century. Before the nineteenth century, “the living and working conditions faced by farmworkers were not markedly different from those of industrial workers” (Thompson & Wiggins, 2002, p. 140). However, continuing into the twentieth century and especially through the New Deal reforms, the same degree of protection toward industrial workers did not extend to workers in the agricultural sector (Thompson & Wiggins, 2002). The lack of regulation in the agricultural sector has persisted. In addition, the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) sparked the flight of about 400,000 Mexican immigrants to the United States between 2000-2005 because American farmers were given large subsidies and could export agricultural goods cheaply; Mexican famers migrated to the United States because it became difficult to earn wages in Mexico from exports to the United States (Delgado-Wise & Márquez Covarrubias, 2007). Indigenous Mexicans, especially from the state of Oaxaca, made up a large proportion of those who fled. -

Public Health in Mexico Program Handbook 2019

Universidad Panamericana PUBLIC HEALTH IN MEXICO PROGRAM HANDBOOK 2019 Public Health in Mexico, Summer 2019 Program Handbook PROGRAM INFORMATION........................................................................................................... 3 PROGRAM TEAM ............................................................................................................................... 3 TENTATIVE PROGRAM SCHEDULE & ACTIVITIES ............................................................................... 3 UNIVERSIDAD PANAMERICANA CAMPUS………………………………………………………………….3 COURSE DESCRIPTIONS ................................................................................................................... 4 PUBLIC HEALTH IN MEXICO .............................................................................................................. 4 HEALTHCARE SYSTEM AND POLICY IN MEXICO .................................................................................. 4 SPANISH LANGUAGE ......................................................................................................................... 4 HISTORY AND CULTURE OF MEXICO .................................................................................................. 4 TRANSCRIPT & CREDIT TRANSFER .................................................................................................... 4 FRIDAY EXCURSIONS & STUDY TRIPS ............................................................................................... 5 ACCOMMODATIONS & MEALS .......................................................................................................... -

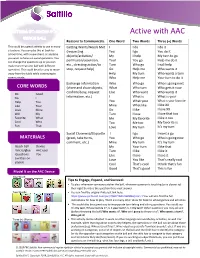

Active with AAC

Active with AAC Reasons to Communicate One Word Two Words Three (+) Words This could be a great activity to use in many Getting Wants/Needs Met I I do I do it situations. You can play this at back-to- (requesting You I go You do it school time, with a new client, or anytime objects/activities/ My I help My turn to go you want to focus on social questions. You can change the questions up or you can permission/attention, Your You go Help me do it make more than one ball with different etc., directing action/to Turn Who go I will help stop, request help) Go Help me Who wants it questions. This could be a fun way to move away from the table while continuing to Help My turn Who wants a turn communicate. Who Help me Your turn to do it Exchange Information Who Who go Who is going next CORE WORDS (share and show objects, What Who turn Who gets it now confirm/deny, request Like Who want Who wants it Do Good Go I information, etc.) I What is What is your Help You You What your What is your favorite Like Your Mine What like I like XX Love Mine Go I like I love XX Will My Turn I love I love that too Favorite What Me My favorite I like it too Cool Who Too Me too My favorite is Fun That Love My turn It’s my turn Social Closeness/Etiquette I I go I want a go MATERIALS (greet, take turns, You Who go Who is going now comment, etc.) Mine My turn It’s my turn Beach ball Device My Your turn I like that Velcro/glue AAC user Turn I like I like it Questions You Like I love I love it (written on Love You like That’s really cool paper) Cool That’s cool I think that’s fun Good That’s good This is fun Model It on the AAC Device One Word: Tips to Engage, Expand, and Succeed: • To play: whenever someone catches the ball, whatever question is touching (or is closest to) their right thumb is the question they must answer. -

![2010 Census Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Summary File— (Name of State) [Machine-Readable Data Files]/Prepared by the U.S](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2084/2010-census-redistricting-data-public-law-94-171-summary-file-name-of-state-machine-readable-data-files-prepared-by-the-u-s-812084.webp)

2010 Census Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Summary File— (Name of State) [Machine-Readable Data Files]/Prepared by the U.S

2010 Census Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Summary File Issued January 2011 2010 Census of Population and Housing PL/10-2 (RV) Technical Documentation U.S. Department of Commerce U S C E N S U S B U R E A U Economics and Statistics Administration U.S. CENSUS BUREAU Helping You Make Informed Decisions For additional information concerning the Census Redistricting Data Program, contact the Census Redistricting Data Office, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC 20233, or phone 301-763-4039. For additional information concerning the DVD and software issues, contact the Administrative and Customer Services Division, Electronic Products Development Branch, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC 20233, or phone 301-763-7710. For additional information concerning the files, contact the Customer Liaison and Marketing Services Office, Customer Services Center, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC 20233, or phone 301-763-INFO (4636). For additional information concerning the technical documentation, contact the Administrative and Customer Services Division, Electronic Products Development Branch, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC 20233, or phone 301-763-8004. 2010 Census Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Summary File Issued January 2011 2010 Census of Population and Housing PL/10-2 (RV) Technical Documentation U.S. Department of Commerce Gary Locke, Secretary Rebecca M. Blank, Acting Deputy Secretary Economics and Statistics Administration Rebecca M. Blank, Under Secretary for Economic Affairs U.S. CENSUS BUREAU Robert M. Groves, Director SUGGESTED CITATION FILES: 2010 Census Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Summary File— (name of state) [machine-readable data files]/prepared by the U.S. -

The Rare Split of Amuzgo Verbal Inflection Enrique L

Agreeing with subjects in number: The rare split of Amuzgo verbal inflection Enrique L. Palancar, Timothy Feist To cite this version: Enrique L. Palancar, Timothy Feist. Agreeing with subjects in number: The rare split of Amuzgo verbal inflection. Linguistic Typology, De Gruyter, 2015, 93 (3), 10.1515/lingty-2015-0011. hal- 01247113 HAL Id: hal-01247113 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01247113 Submitted on 21 Dec 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Agreeing with subjects in number: The rare split of Amuzgo verbal inflection Enrique L. Palancar, Structure et Dynamique des Langues (UMR8292), CNRS Timothy Feist, Surrey Morphology Group, University of Surrey To appear in Linguistic Typology 19:3, 2015 “[T]he formal expression of these categories involves a great deal of suppletion and morphologically conditioned internal modification and fusion, resulting in an extreme degree of irregularity. Indeed, Amuzgo morphology is so irregular that we have been tempted to call it a lexical language; that is, a language where the ideal seems to be for each form to have an idiosyncratic individuality rather than for it to be productively generatable [sic.].” (Smith-Stark and Tapia, 1986) Abstract Verbs in San Pedro Amuzgo, an Oto-Manguean language of Mexico, often have two different stems in the paradigm, one used with singular subjects and the other with plural subjects. -

Triqui Tonal Coarticulation and Contrast Preservation in Tonal Phonology∗

TRIQUI TONAL COARTICULATION AND CONTRAST PRESERVATION IN TONAL PHONOLOGY∗ CHRISTIAN DICANIO Haskins Laboratories Tonal languages vary substantially in the degree in which coarticulation occurs across word boundaries. In languages like Mandarin, coarticulation is strong and results in extensive variation in how tones are produced (Xu, 1994). In languages like Thai, coarticulation is noticeably weaker and does not result in the same degree of tonal overlap (Gandour, Tum- tavitikul, and Satthamnuwong, 1999). Just what accounts for such differences? The current study examines how tones are coarticulated in Itunyoso Triqui (IT), an Oto-Manguean lan- guage with nine lexical tones, across different contexts and speech rates. The findings show that contour tones influence the production of adjacent tones significantly more than level tones do, often resulting in tonal assimilation. Though, the degree of assimilation across contexts was relatively small in comparison to previous work on tonal coarticulation. Tonal dissimilation between the highest and lowest tones in the experiment and F0 range expan- sion during faster speech rate were also observed. These findings suggest that IT speakers actively preserve tonal contrasts in their language in conditions where one would antici- pate the greatest mechanical overlap between tones. The ramifications of this research are discussed in relation to the literature on tone production and perception. This research pre- dicts that tonal languages which more heavily weigh F0 height as a tonal cue undergo less coarticulatory variation than those which weigh F0 slope more heavily. Keywords: tone, coarticulation, Oto-Manguean, speech rate Introduction In the initial stage of describing a tone language, one typically examines how each lexical tone is pro- duced in isolated words. -

What Are Core Words Anyway? Let Us Help You Get Started! Part 1 Goals for AAC Users

What Are Core Words Anyway? Let Us Help You Get Started! Part 1 Introductions and Presentation Goals Goals for AAC Users a. Learn cause and effect Reasons why we communicate b. Communicate with peers 1) Naming and adults c. Learn Language 2) Greeting d. Initiate – not just respond 3) Commenting e. Make friends 4) Requesting Objects f. Social skills g. Learn educational content 5) Protesting h. Participate in class or 6) Requesting Information workplace 7) Responding i. Gain independence – say 8) Requesting Action what they want to say! 9) Responding to Request 10) Regulating Conversational Behavior 11) Relaying Past Events Commenting 12) Stating Greeting Naming Activity to Build Communication Responding Requesting Objects Protesting Requesting Information Requesting Action Making a Snack Reading a Book Suggested Activity https://saltillo.com/ 1 © 2020 PRC-Saltillo. Non-commercial reprint rights for clinical or personal use granted with inclusion of copyright notice. Commercial use prohibited; may not be used for resale. Contact PRC-Saltillo for questions regarding permissible uses. Understand the target Various ways to look at language development, but ultimately they lead us down the same path • Developmental Milestones • Language acquisition stages • Browns Stages How can we aim for the target? Use CORE VOCABULARY! Notes Core vocabulary is: o Reusable across contexts, o Made up of approximately 250-400 words that account for 80% of our utterances, and is the same across gender, age, topic, setting, and disability. o Includes pronouns, verbs, adjectives, questions, interjections, prepositions and adverbs. Which class of words is missing? ______________ https://saltillo.com/ 2 © 2020 PRC-Saltillo. Non-commercial reprint rights for clinical or personal use granted with inclusion of copyright notice. -

Proposal for Generation Panel for Latin Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone

Generation Panel for Latin Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone Proposal for Generation Panel for Latin Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone Table of Contents 1. General Information 2 1.1 Use of Latin Script characters in domain names 3 1.2 Target Script for the Proposed Generation Panel 4 1.2.1 Diacritics 5 1.3 Countries with significant user communities using Latin script 6 2. Proposed Initial Composition of the Panel and Relationship with Past Work or Working Groups 7 3. Work Plan 13 3.1 Suggested Timeline with Significant Milestones 13 3.2 Sources for funding travel and logistics 16 3.3 Need for ICANN provided advisors 17 4. References 17 1 Generation Panel for Latin Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone 1. General Information The Latin script1 or Roman script is a major writing system of the world today, and the most widely used in terms of number of languages and number of speakers, with circa 70% of the world’s readers and writers making use of this script2 (Wikipedia). Historically, it is derived from the Greek alphabet, as is the Cyrillic script. The Greek alphabet is in turn derived from the Phoenician alphabet which dates to the mid-11th century BC and is itself based on older scripts. This explains why Latin, Cyrillic and Greek share some letters, which may become relevant to the ruleset in the form of cross-script variants. The Latin alphabet itself originated in Italy in the 7th Century BC. The original alphabet contained 21 upper case only letters: A, B, C, D, E, F, Z, H, I, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, V and X.