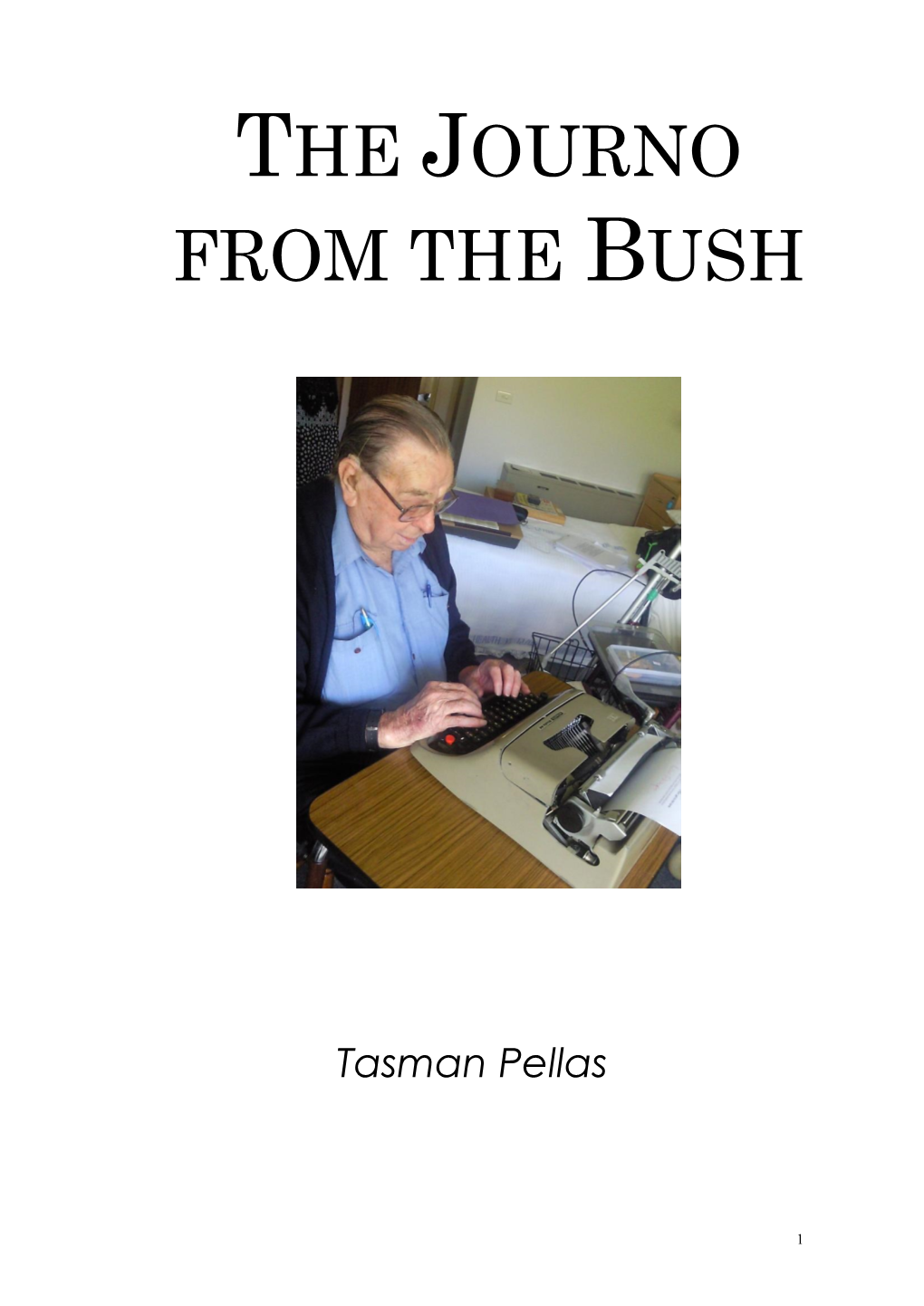

Innumerable People Have Asked Me How I Got My First Name

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finnish Title Artist ID

Finnish Title Artist ID 0010 APULANTA 300001 008 (HALLAA) APULANTA 300002 12 APINAA NYLON BEAT 300003 12 APINAA NYLON BEAT 300004 1963 - VIISITOISTA VUOTTA MYÖHEMMIN LEEVI AND THE LEAVINGS 305245 1963 - VIISITOISTA VUOTTA MYÖHEMMIN LEEVI AND THE LEAVINGS 305246 1972 ANSSI KELA 300005 1972 ANSSI KELA 300006 1972 ANSSI KELA 300007 1972 MAIJA VILKKUMAA 304851 1972 (CLEAN) MAIJA VILKKUMAA 304852 2080-LUVULLA ANSSI KELA 304853 2080-LUVULLA SANNI 304759 2080-LUVULLA SANNI 304888 2080-LUVULLA (CLEAN) ANSSI KELA 304854 506 IKKUNAA MILJOONASADE 304793 A VOICE IN THE DARK TACERE 304024 AALLOKKO KUTSUU GEORG MALMSTEN 300008 AAMU ANSSI KELA 300009 AAMU ANSSI KELA 300010 AAMU ANSSI KELA 300011 AAMU PEPE WILLBERG 300012 AAMU PEPE WILLBERG 300013 AAMU PEPE WILLBERG 304580 AAMU AIRISTOLLA OLAVI VIRTA 300014 AAMU AIRISTOLLA OLAVI VIRTA 304579 AAMU TOI, ILTA VEI JAMPPA TUOMINEN 300015 AAMU TOI, ILTA VEI JAMPPA TUOMINEN 300016 AAMU TOI, ILTA VEI JAMPPA TUOMINEN 300017 AAMUISIN ZEN CAFE 300018 AAMUKUUTEEN JENNA 300019 AAMULLA RAKKAANI NÄIN LEA LAVEN 300020 AAMULLA RAKKAANI NÄIN LEA LAVEN 300021 AAMULLA VARHAIN KANSANLAULU 300022 AAMUN KUISKAUS STELLA 300023 AAMUN KUISKAUS STELLA 304576 AAMUUN ON HETKI AIKAA CHARLES PLOGMAN 300024 AAMUUN ON HETKI AIKAA CHARLES PLOGMAN 300025 AAMUUN ON HETKI AIKAA CHARLES PLOGMAN 300026 AAMUYÖ MERJA RASKI 300027 AAVA EDEA 300028 AAVERATSASTAJAT DANNY 300029 ADDICTED TO YOU LAURA VOUTILAINEN 300030 ADIOS AMIGO LEA LAVEN 300031 AFRIKAN TÄHTI ANNIKA EKLUND 300032 AFRIKKA, SARVIKUONOJEN MAA EPPU NORMAALI 300033 AI AI JUSSI TUIJA -

Community Services Directory 2010/2011

MOUNT ALEXANDER SHIRE Community Services Directory 2010/2011 This directory was compiled by the Mount Alexander Community Information Centre with the support of Mount Alexander Shire Council. Council acknowledges the valuable work undertaken by this organisation in compiling the directory. Telephone: 5472 2688 Email: [email protected] Directory Website: http://users.vic.chariot.net.au/~cic Mount Alexander Community Services Directory Mount Alexander Shire Council Community Services Directory Table Of Contents ACCOMMODATION . 1 Caravan Parks . 1 Emergency Accommodation . 1 Holiday . 1 Hostels . 2 Nursing Homes . 2 Public Housing . 2 Tenancy . 3 AGED AND DISABILITY SERVICES . 4 Aids and Appliances . 4 Intellectual Disabilities . 4 Home Services . 5 Learning Difficulties . 5 Psychiatric Disabilities . 5 Physical Disabilities . 6 Senior Citizen's Centres . 6 Rehabilitation . 7 Respite Services . 7 ANIMAL WELFARE . 8 Animal Welfare Groups . 8 Boarding Kennels . 8 Dog Grooming . 8 Equine Dentist . 8 Veterinary Clinics . 9 ANIMALS . 9 Cats . 9 Dingos . 9 Dogs . 9 Goats . 9 Horses . 9 Pony Clubs . 10 Pigeons . 10 ANTIQUES AND SECONDHAND GOODS . 10 Antique Shops . 10 Opportunity Shops . 10 Secondhand Goods . 11 ARTS AND CRAFTS . 11 Ballet . 11 Dancing . 11 Drama . 12 Drawing . 12 Embroidery . 12 Film . 13 Hobbies . 13 Instruction . 13 Knitting . 15 Music and Singing . 15 Painting . 16 Photography . 16 Picture Framing . 17 Quilting . 17 Spinning and Weaving . .. -

Slate.Com Table of Contents Faith-Based a Skeptic's Guide to Passover

Slate.com Table of Contents faith-based A Skeptic's Guide to Passover fighting words ad report card Telling the Truth About the Armenian Genocide Credit Crunch foreigners Advanced Search Why Israel Will Bomb Iran books foreigners Why Write While Israel Burns? Too Busy To Save Darfur change-o-meter foreigners Supplemental Diet No Nukes? No Thanks. change-o-meter gabfest Unclenched Fists The Velvet Snuggie Gabfest change-o-meter grieving Dogfights Ahead The Long Goodbye change-o-meter human guinea pig Big Crowds, Few Promises Where There's E-Smoke … chatterbox human nature A Beat-Sweetener Sampler Sweet Surrender corrections human nature Corrections Deeper Digital Penetration culture gabfest jurisprudence The Culture Gabfest, Empty Calories Edition Czar Obama dear prudence jurisprudence It's a Jungle Down There Noah Webster Gives His Blessing drink jurisprudence Not Such a G'Day Spain's Most Wanted: Gonzales in the Dock dvd extras moneybox Wauaugh! And It Can't Count on a Bailout explainer movies Getting High by Going Down Observe and Report explainer music box Heated Controversy When Rock Stars Read Edmund Spenser explainer music box Why Is Gmail Still in Beta? Kings of Rock explainer my goodness It's 11:48 a.m. Do You Know Where Your Missile Is? Push a Button, Change the World faith-based other magazines Passionate Plays In Facebook We Trust faith-based poem Why Was Jesus Crucified? "Bombs Rock Cairo" Copyright 2007 Washingtonpost.Newsweek Interactive Co. LLC 1/125 politics today's papers U.S. Department of Blogging Daring To Dream It's -

Full Day Hansard Transcript (Legislative Assembly, 11 May 2011, Corrected Copy) Extract from NSW Legislative Assembly Hansard and Papers Wednesday, 11 May 2011

Full Day Hansard Transcript (Legislative Assembly, 11 May 2011, Corrected Copy) Extract from NSW Legislative Assembly Hansard and Papers Wednesday, 11 May 2011. GOVERNOR'S SPEECH: ADDRESS-IN-REPLY Fourth Day's Debate Debate resumed from an earlier hour. Mr GUY ZANGARI (Fairfield) [6.17 p.m.] (Inaugural Speech): Mr Deputy-Speaker, I congratulate you on your election as the Deputy-Speaker. We look forward to your distinguished service to the House and to the people of New South Wales. It is a privilege to address the House this evening. It is a sincere honour to be elected to the oldest Parliament in the country and the Fifty-fifth Parliament of New South Wales. It is equally an honour to be the elected representative for Fairfield. Life's journey is characterised by the people you meet and the family you are part of. People are shaped and formed by their experiences throughout life, and I need to thank many people for shaping and moulding me into the person I am today. My life has been an experience of two halves. The first is to have grown up in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney with my parents and siblings; the second is to have been tertiary educated and to work, live and raise a family in the outer-western Sydney suburbs. I am always a westie and proud of it. I begin by acknowledging the people who assisted the Fairfield Labor Party campaign. My campaign director, Adrian Boothman, is a former student of Patrician Brothers' College, Fairfield. His tireless efforts, constant support and advice were and remain invaluable. -

Introduction & Recommendations

Separate Attachment COM 20A Ordinary Meeting of Council 26 April 2016 MOUNT ALEXANDER SHIRE THEMATIC HERITAGE STUDY ARCHITECTS CONSERVATION Introduction & CONSULTANTS Recommendations TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Brief 2 1.3 Study Area 2 1.4 Earlier Reports 3 1.5 Study Team 3 1.5 Acknowledgements 3 2 Methodology 2.1 General 4 2.2 Survey Work 4 2.3 Research 4 2.4 Consultation 5 3 The Themes 3.1 The Framework 6 3.2 Overview of the Themes 6 4 Recommendations 4.1 Introduction 8 4.2 Existing Schedule to the Heritage Overlay 8 4.3 Further Review Work 9 Mount Alexander Shire Thematic Heritage Study Introduction & Recommendations Volume 1 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background This Thematic Heritage Study has been prepared for the Shire of Mount Alexander by RBA Architects and Conservation Consultants. It consists of two sections: Volume 1 – Introduction & Recommendations. This volume outlines the process by which the thematic history was prepared as well as recommending some areas for further investigation and places of potential significance. Volume 2 – A Thematic History of the Shire according to nine themes and concluding with a Statement of Significance. The need for the preparation of an all-encompassing, Shire-wide thematic history had been identified as a key priority in the local Heritage Strategy 2012-2016.1 A thematic history has previously been prepared for sections of Mount Alexander Shire, within the heritage studies of the former shires of Metcalfe and Newstead. In addition, although many places are protected by heritage overlays further assessment was needed according to the Heritage Strategy as follows: Protecting & Managing There are over 1000 places in the Schedule to the Heritage Overlay however these are unevenly spread across the Shire. -

The Essay Prepared by Historian Professor Paul Ashton

1987: The Year of New Directions RELEASE OF 1987 NSW CABINET PAPERS Release of 1987 NSW Cabinet Papers 2 Table of Contents 1987: The Year of New Directions ......................................................................................................... 3 Dual Occupancy and the Quarter-acre Block ...................................................................................... 4 The Sydney Harbour Tunnel ................................................................................................................ 5 The Bicentenary .................................................................................................................................. 6 Sydney City Council Bill ....................................................................................................................... 6 The University of Western Sydney ...................................................................................................... 7 Casino Tenders .................................................................................................................................... 8 Chelmsford Private Hospital ............................................................................................................... 9 Workers’ Compensation ................................................................................................................... 10 Establishment of the Judicial Commission ........................................................................................ 10 1987 NSW Cabinet ............................................................................................................................... -

Sex and Disability

Sex and diSability Sex and diSability RobeRt McRueR and anna Mollow, editoRs duke univerSity PreSS duRhaM and london 201 2 © 2012 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ♾ Designed by Nicole Hayward Typeset in Minion Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data and republication acknowledgments appear on the last printed page of this book. ContentS Acknowledgments / ix Introduction / 1 AnnA Mollow And RobeRt McRueR Part i: aCCeSS 1 A Sexual Culture for Disabled People / 37 tobin SiebeRS 2 Bridging Theory and Experience: A Critical- Interpretive Ethnography of Sexuality and Disability / 54 RuSSell ShuttlewoRth 3 The Sexualized Body of the Child: Parents and the Politics of “Voluntary” Sterilization of People Labeled Intellectually Disabled / 69 Michel deSjARdinS Part ii: HiStorieS 4 Dismembering the Lynch Mob: Intersecting Narratives of Disability, Race, and Sexual Menace / 89 Michelle jARMAn 5 “That Cruel Spectacle”: The Extraordinary Body Eroticized in Lucas Malet’s The History of Sir Richard Calmady / 108 RAchel o’connell 6 Pregnant Men: Modernism, Disability, and Biofuturity / 123 MichAel dAvidSon 7 Touching Histories: Personality, Disability, and Sex in the 1930s / 145 dAvid SeRlin Part iii: SPaCeS 8 Leading with Your Head: On the Borders of Disability, Sexuality, and the Nation / 165 nicole MARkotiĆ And RobeRt McRueR 9 Normate Sex and Its Discontents / 183 Abby l. wilkeRSon 10 I’m Not the Man I Used to Be: Sex, hiv, and Cultural “Responsibility” / 208 chRiS bell Part iv: liveS 11 Golem Girl Gets Lucky / 231 RivA lehReR 12 Fingered / 256 lezlie FRye 13 Sex as “Spock”: Autism, Sexuality, and Autobiographical Narrative / 263 RAchAel GRoneR Part v: deSireS 14 Is Sex Disability? Queer Theory and the Disability Drive / 285 AnnA Mollow 15 An Excess of Sex: Sex Addiction as Disability / 313 lennARd j. -

Finalised Priority Assessment List for 2010-11 for the Commonwealth Heritage List

Finalised Priority Assessment List for the Commonwealth Heritage List for 2010-2011 Assessment Name of Place Description Completion Date New South Wales Albury Post Office 570 Dean Street, on the north-east corner Dean and Kiewa Streets, Albury. 30/06/2011 Armidale Post Office 158 Beardy Street, corner Faulkner Street, Armidale. 30/06/2011 Bankstown Airport Air Traffic Control Tower Located at Bankstown Airport, Bankstown, Tower Road, comprising only the Bankstown Airport 30/06/2011 Control Tower. Botany Post Office 2 Banksia Street, corner Wilson Lane, Botany. 30/06/2011 Broken Hill Post Office 258-260 Argent Street, corner of Chloride Street, Broken Hill. 30/06/2011 Casino Post Office 102 Barker Street, Casino. 30/06/2011 Forbes Post Office 118 Lachlan Street, corner Court Street, Forbes. 30/06/2011 Glen Innes Post Office 319 Grey Street, corner Meade Street, Glen Innes. 30/06/2011 Goulburn Post Office 165 Auburn Street, Goulburn. 30/06/2011 Inverell Post Office 97-105 Otho Street, Inverell. 30/06/2011 Kempsey Post Office 3-5 Smith Street, corner Belgrave Street, Kempsey. 30/06/2011 Kiama Post Office 24 Terralong Street, corner Manning Street, Kiama. 30/06/2011 Llandilo International Transmitter Station About 600ha, Stoney Creek Road, Shanes Park, comprising the whole of Lot 1 DP447543. 30/06/2011 Macksville Post Office Cowper Street, corner River Street, Macksville. 30/06/2011 Maitland Post Office 381 High Street, corner Bourke Street, Maitland. 30/06/2011 Mudgee Post Office 80 Market Street, corner Perry Street, Mudgee. 30/06/2011 Muswellbrook Post Office 7 Bridge Street, Muswellbrook. 30/06/2011 Narrabri Post Office and former Telegraph 138-140 Maitland Street, corner Doyle Street, Narrabri. -

Extract Catalogue for Auction

Page:1 Feb 29 & Mar 1, 2020 Lot Type Grading Description Est $A AUSTRALIAN PICTURE POSTCARDS See also World Postcards: Lots 995 to 1009. 313 C Eclectic group mostly Queensland (hardly any Brisbane) noted 1909 'Church of England, Ipswich', some real photo cards including 'Central State School, Mackay' & 'Gray Street, Crow's Nest', various Townsville & Islands scenes, also Sydney 'Book Post' panorama cards x8, then lots of 'moderns' from the 1950s onwards, etc, condition variable but mostly fine. 200 Ex Lot 314 314 C Handy selections from ACT x26 mostly 1940s & 1950s including Mount Stromlo Observatory group, Cotter Dam, US Embassy, etc; NT x32 mostly 1950s to 1970s including Albert Namatjira group & Cyclone Tracy group; and Western Australia x24 including Murray, Valentine & Royal real photo types; generally fine to superb & mostly unused. (82) 400 315 C Box with many rural & agricultural scenes plus a good range of bush-artist cards, military, ships, automobiles including some photographs, etc, generally fine to very fine. (150 approx) 150 Ex Lot 316 316 C A/A- Beautiful group of Robert Jolley Undivided Backs each with State emblem plus black & white view, all States represented, plus one from a different series, fine to very fine unused. (15) 150 Ex Lot 317 317 C Railways steam locomotives, trains & stations noted Qld Toowoomba 'Spring Bluff' & 'Sydney Mail', SA Clare, Glenelg, Mt Lofty x3 different, Tas Campania 'Railway Accident', Vic Belgrave 'Puffing Billy', Castlemaine, Echuca 'Murray Bridge', Flinders Street 'Southern Mail', Gembrook, Kyabram Station, Monbulk, South Yarra 'Train Passing Through Flood Waters', Sunshine 'Railway Accident' 1908, Walhalla 'Train on Thompson Bridge', Warragul, etc, plus Trams Victor Harbor 'Old Horse Tram', Hobart 'Municipal Tramways' double-decker twin-car real photo plus another on Elizabeth Street with 'Wolfe's Schnapps' advertising, also Ballarat, Bendigo, etc, mostly fine. -

Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Communications

Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Communications Answers to Senate Estimates Questions on Notice Additional Estimates Hearings February 2016 Communications Portfolio Australia Post Question No: 178(d) Australia Post Hansard Ref: Written, 19/02/2016 Topic: Land Costs Senator Ludwig, Joe asked: 1. How much land (if any) does the Department or agencies or authorities or Government Corporation within each portfolio own or lease? 2. Please list by each individual land holding, the size of the piece of land, the location of that piece of land and the latest valuation of that piece of land, where that land is owned or leased by the Department, or agency or authority or Government Corporation within that portfolio? (In regards to this question please ignore land upon which Australian Defence force bases are located. Non-Defence Force base land is to be included) 3. List the current assets, items or purse (buildings, facilities or other) on the land identified above. (a) What is the current occupancy level and occupant of the items identified in (3)? (b) What is the value of the items identified in (3)? (c) What contractual or other arrangements are in place for the items identified in (3)? 4. How many buildings (if any) does the Department or agencies or authorities or Government Corporation within each portfolio own or lease? 5. Please list by each building owned, its name, the size of the building in terms of square metres, the location of that of that building and the latest valuation of that building, where that building is owned by the Department, or agency or authority or Government Corporation within that portfolio? (In regards to this question please ignore buildings that are situated on Australian Defence force bases. -

Thesis August

Chapter 1 Introduction Section 1.1: ‘A fit place for women’? Section 1.2: Problems of sex, gender and parliament Section 1.3: Gender and the Parliament, 1995-1999 Section 1.4: Expectations on female MPs Section 1.5: Outline of the thesis Section 1.1: ‘A fit place for women’? The Sydney Morning Herald of 27 August 1925 reported the first speech given by a female Member of Parliament (hereafter MP) in New South Wales. In the Legislative Assembly on the previous day, Millicent Preston-Stanley, Nationalist Party Member for the Eastern Suburbs, created history. According to the Herald: ‘Miss Stanley proceeded to illumine the House with a few little shafts of humour. “For many years”, she said, “I have in this House looked down upon honourable members from above. And I have wondered how so many old women have managed to get here - not only to get here, but to stay here”. The Herald continued: ‘The House figuratively rocked with laughter. Miss Stanley hastened to explain herself. “I am referring”, she said amidst further laughter, “not to the physical age of the old gentlemen in question, but to their mental age, and to that obvious vacuity of mind which characterises the old gentlemen to whom I have referred”. Members obviously could not afford to manifest any deep sense of injury because of a woman’s banter. They laughed instead’. Preston-Stanley’s speech marks an important point in gender politics. It introduced female participation in the Twenty-seventh Parliament. It stands chronologically midway between the introduction of responsible government in the 1850s and the Fifty-first Parliament elected in March 1995. -

Theatre | Film | Tv Fall 2015 |

HAL LEONARD THE BEST IN MUSIC | THEATRE | FILM | TV FALL 2015 | PERFORMING ARTS Hal Leonard Books | Backbeat Books | Applause Books | Amadeus Press TABLE OF CONTENTS Frontlist Titles Backbeat Books ....................................................................2 Hal Leonard Books ..............................................................22 Amadeus Press ...................................................................32 Applause Books ...................................................................35 Opus Books .........................................................................54 Hal Leonard .........................................................................57 Vintage Guitar ......................................................................58 Recently Released ...............................................................59 Previously Announced .........................................................63 Songbooks & Music Instruction ...........................................67 Selected Backlist Titles MUSIC Biographies .........................................................................79 Business ..............................................................................80 History .................................................................................81 Education ............................................................................81 Guitar ..................................................................................82 Audio Technology ................................................................84