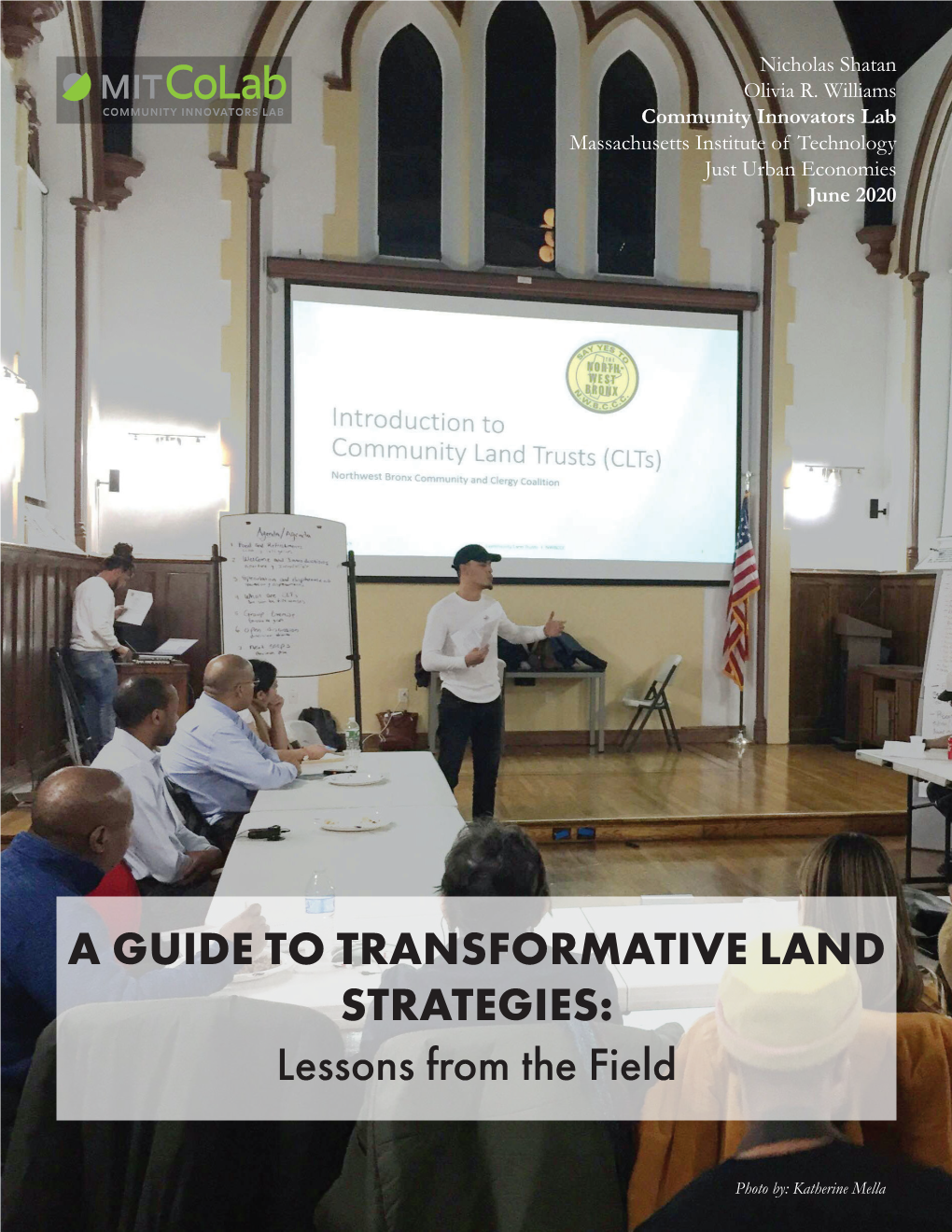

A GUIDE to TRANSFORMATIVE LAND STRATEGIES: Lessons from the Field

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz

BOOK SYMPOSIUM: ON GLOBAL JUSTICE On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz n appealing and original aspect of Mathias Risse’s book On Global Justice is his argument for humanity’s collective ownership of the A earth. This argument focuses attention on states’ claims to govern ter- ritory, to control the resources of that territory, and to exclude outsiders. While these boundary claims are distinct from private ownership claims, they too are claims to control scarce goods. As such, they demand evaluation in terms of dis- tributive justice. Risse’s collective ownership approach encourages us to see the in- ternational system in terms of property relations, and to evaluate these relations according to a principle of distributive justice that could be justified to all humans as the earth’s collective owners. This is an exciting idea. Yet, as I argue below, more work needs to be done to develop plausible distribution principles on the basis of this approach. Humanity’s collective ownership of the earth is a complex notion. This is because the idea performs at least three different functions in Risse’s argument: first, as an abstract ideal of moral justification; second, as an original natural right; and third, as a continuing legitimacy constraint on property conventions. At the first level, collective ownership holds that all humans have symmetrical moral status when it comes to justifying principles for the distribution of earth’s original spaces and resources (that is, excluding what has been man-made). The basic thought is that whatever claims to control the earth are made, they must be compatible with the equal moral status of all human beings, since none of us created these resources, and no one specially deserves them. -

The Costs and Benefits of Government Control: Evidence from China's Collectively-Owned Enterprises Jiangyong Lu /Peking Unive

The Costs and Benefits of Government Control: Evidence from China’s Collectively-Owned Enterprises Jiangyong Lu /Peking Universitya Zhigang Tao/University of Hong Kongb Zhi Yang/Hua Zhong University of Science & Technologyc May 2009 Abstract: China’s collectively-owned enterprises are unconventional, as they are nominally owned by those people residing in the areas where the enterprises are located but effectively controlled by the local governments. This study finds that collectively-owned enterprises, once being privatized, encounter an increase in the cost of goods sold to sales ratio but manage to lower down the managerial expenses to sales ratio. The findings imply that local government officials may help collectively-owned enterprises gain access to cheaper production inputs, but they may use those enterprises to pursue private benefits, thereby shedding lights on the costs and benefits of government control. JEL classification codes: L33, P31, D23 Keywords: China’s collectively-owned enterprises, costs and benefits of government control, managerial expenses, and cost of goods sold a Department of Strategic Management, Guanghua School of Management, Peking University, Beijing, P.R.China. Email: [email protected] b School of Business, and School of Economics and Finance, University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong. Email: [email protected] c School of Management, Huazhong University of Science & Technology, Wuhan, P.R. China. Email: [email protected] The Costs and Benefits of Government Control: Evidence from China’s Collectively-Owned Enterprises May 2009 Abstract: China’s collectively-owned enterprises are unconventional, as they are nominally owned by those people residing in the areas where the enterprises are located but effectively controlled by the local governments. -

Release Tacoma Creates Funding

From: Lyz Kurnitz‐Thurlow <[email protected]> Sent: Wednesday, May 27, 2020 2:08 PM To: City Clerk's Office Subject: Protect Tacoma's Cultural Sector ‐ Release Tacoma Creates Funding Follow Up Flag: Follow up Flag Status: Flagged Tacoma City , I respectfully request that the Tacoma City Council take action and unanimously approve the voter-approved work of Tacoma Creates and the independent Citizen panel’s recommendations on this first major round of Tacoma Creates funding, and to do so on the expedited timeline and process suggested by Tacoma City Staff. Please put these dollars to work to help stabilize the cultural sector. This dedicated funding will flow to more than 50 organizations and ensure that our cultural community remains strong and serves the entire community at a new level of impact and commitment. Lyz Kurnitz-Thurlow [email protected] 5559 Beverly Ave NE Tacoma, Washington 98422 From: Resistencia Northwest <[email protected]> Sent: Tuesday, June 9, 2020 3:57 PM To: City Clerk's Office Subject: public comment ‐ 9 June 2020 Attachments: Public Comment ‐ 9 June 2020 ‐ Resistencia.pdf Follow Up Flag: Follow up Flag Status: Flagged Our comment for tonight's City Council meeting is attached below. There are questions - when can we expect answers? Thanks, La Resistencia PO Box 31202 Seattle, WA 98103 Web | Twitter | Instagram | Facebook Public Comment, City of Tacoma 9 June 2020 From: La Resistencia The City of Tacoma has only recently begun to recognize the violence, racism, and insupportability of a private prison for immigration in a polluted port industrial zone. We continue to call for the City of Tacoma to show support and solidarity for those in detention at NWDC, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. -

An Abolitionist Journal VOL

IN THE BELLY an abolitionist journal VOL. 2 JULY + BLACK AUGUST 2020 Contents Dear Comrades ������������������������������������� 4 Let’s Not Go Back To Normal ������������������������� 6 Prison in a Pandemic �������������������������������� 9 What Abolition Means to Me ������������������������� 15 Practicing Accountability ���������������������������� 16 So Describable �������������������������������������� 17 The Imprisoned Black Radical Intellectual Tradition �� 18 Cannibals ������������������������������������������� 21 8toAbolition to In The Belly Readers ���������������� 27 #8TOABOLITION ����������������������������������� 28 Abolition in Six Words ������������������������������ 34 Yes, I know you ������������������������������������� 36 Fear ������������������������������������������������ 38 For Malcolm U.S.A. ��������������������������������� 43 Are Prisons Obsolete? Discussion Questions ������������ 44 Dates in Radical History: July ����������������������� 46 Dates in Radical History: Black August �������������� 48 Brick by Brick, Word by Word ����������������������� 50 [Untitled] ������������������������������������������� 52 Interview with Abolitionist, Comrade, and IWOC Spokes- Published and Distributed by person Kevin Steele �������������������������������� 55 True Leap Press Pod-Seed / A note about mail ����������������������� 66 P.O. Box 408197 Any City USA (Dedicated to Oscar Grant) ������������ 68 Chicago, IL 60640 Resources ������������������������������������������ 69 Write for In The Belly! ������������������������������� -

Ord 28624 Tacoma Gun and Ammunition Tax

From: richard.cosner <[email protected]> Sent: Tuesday, June 16, 2020 5:08 PM To: City Clerk's Office Subject: Ord 28624 Tacoma Gun and Ammunition Tax Follow Up Flag: Follow up Flag Status: Flagged Council, Mayor, I understand the tax is coming under review here in June. I voiced my opinion back then that I would no longer spend any of my income in the City of Tacoma, and I have kept that promise to date! As your constituents testify before you today, let me remind you of the troubles our world is encountering, let me remind you of the failed tax in Freattle, let me remind you how the tax failed to stop any violence, let me remind you how many businesses left Freattle, let me remind you of the Tourism lost in Freattle! Will I need to remind you to turn off the lights as we leave Tacoma, just like Freattle is losing ground to anarchists, mob violence, riots, a dwindling and devasted Police Force with no desire to help those in need! Do I need to remind you of what used to be a picturesque Seattle that has turned into a sesspool of homeless camps, drug users, and mentally deficient people clammering for charity from the Freattlites that remain! This is the road that you are turning down, should you follow this road of failed policies and actions we will see the same failures over run Tacoma making it the same as all those other Cities that attempted archaically designed and failed policies. All of California-failed, bankrupt! Chicago- the worst violence in the Country. -

Tenants United

TENANTS UNITED: NAVIGATING ALLIES AND ADVERSARIES IN HOUSING MOVEMENTS BY Caitlin Waickman B.A. Fordham University, 2012 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTERS OF ARTS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF URBAN STUDIES AT FORDHAM UNVERSITY NEW YORK May, 2014 UMI Number: 1561147 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 1561147 Published by ProQuest LLC (2014). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 Table of Contents Title Page 1 Table of Contents 2 Introduction 3 Renters in the United States 5 The Context of Current Housing Activism 12 Background of Sunset Park 22 Rent Strike in Sunset Park 26 1904 Housing Activism 44 Take Back the Land 50 Allies in the Housing Movement 56 Conclusion 62 Bibliography 65 Appendix 68 Abstract Vita Introduction When a tenant in a rental property notices that their building needs some repair or maintenance, she would first call the super of her building or write a note to her landlord. What happens when, long after the need for repair has been pointed out, the property owner still fails to take action? Buildings throughout New York City are falling into disrepair for a variety of reasons, but in all cases, tenants are left in a precarious situation. -

CRQ Sao Paulo- LDC Cities (14 Points Possible) Name

CRQ Sao Paulo- LDC Cities (14 points possible) Name:_________________________ Rural-to-urban migration in Latin American cities often results in large squatter settlements called favelas surrounding cities such as Sao Paulo. Use the information provided in the data sheets and your background knowledge from class to answer all of the following questions in an essay response. Be sure to check off each question as you answer it. Use the back of paper if necessary. (A) Discuss where the residents of these slums typically come from (1 pt)? Identify and explain one reason why migrants left (push factor) their previous home? (2 pts) (B) Identify and explain two reasons why these migrants are drawn (pulled) to mega-cities like Sao Paulo? (4 pts) (C) Many of the migrants live in favelas or squatter settlements in the cities. Describe favelas in Sao Paulo. (2 pt) Describe where favelas are typically located in Sao Paulo? (1 pt) (D) Identify and explain two problems that Sao Paulo is experiencing because of its size and rapid growth? (4 pts) Data Sheet Brazil Brazil's booming agribusiness targets record 2004 Reuters, 01.07.04, 5:51 PM ET By Peter Blackburn RIO DE JANEIRO, Brazil (Reuters) - Brazil's booming agribusiness trade surplus soared 27 percent to a record $25.8 billion in 2003 from the previous year's record $20.3 billion, and should rise further this year. Commodity superpower Brazil is the world's top exporter of coffee, sugar and orange juice, a leading meat shipper and aims to overtake the United States as the world's top soybean supplier in 2003/04. -

"A Critique of the “Common Ownership of the Earth” Thesis "

Article "A Critique of the “Common Ownership of the Earth” Thesis " Arash Abizadeh Les ateliers de l’éthique / The Ethics Forum, vol. 8, n° 2, 2013, p. 33-40. Pour citer cet article, utiliser l'information suivante : URI: http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1021336ar DOI: 10.7202/1021336ar Note : les règles d'écriture des références bibliographiques peuvent varier selon les différents domaines du savoir. Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d'auteur. L'utilisation des services d'Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d'utilisation que vous pouvez consulter à l'URI http://www.erudit.org/apropos/utilisation.html Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l'Université de Montréal, l'Université Laval et l'Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. Érudit offre des services d'édition numérique de documents scientifiques depuis 1998. Pour communiquer avec les responsables d'Érudit : [email protected] Document téléchargé le 30 juin 2014 03:21 A CRITIQUE OF THE “COMMON OWNERSHIP OF THE EARTH” THESIS 1 ARASH ABIZADEH MCGILL UNIVERSITY 2 0 1 3 ABSTRACT In On Global Justice, Mathias Risse claims that the earth’s original resources are collecti- vely owned by all human beings in common, such that each individual has a moral right to use the original resources necessary for satisfying her basic needs. He also rejects the rival views that original resources are by nature owned by no one, owned by each human in equal shares, or owned and co-managed jointly by all humans. -

Ideologies of Autonomy

Wikipedia @ 20 Ideologies of Autonomy Christopher M. Cox Published on: Jun 11, 2019 Updated on: Jun 21, 2019 Wikipedia @ 20 Ideologies of Autonomy Introduction When I first began routinely using Wikipedia in the early 2000s, my interest owed as much to the model for online curation the site helped to popularize as it did Wikipedia itself. As a model for leveraging the potential of collective online intelligence, emerging modes of online productivity enabled everyday people to help build Wikipedia and, just as importantly for me, proliferated the use of “Wikis” to centralize and curate content ranging from organizational workflows to repositories for the intricacies of pop culture franchises. As a somewhat obsessive devotee of the television series Lost (2004-2011), I was especially enthusiastic about the latter, since the Lostpedia wiki was an essential part of my engagement with the series’ themes, mysteries, and motifs. On an almost daily basis during the show’s run, I found myself plunging ever deeper into Lostpedia, gleaming reminders of previous plot points and character interactions and using this knowledge to piece together ideas about the series’ sprawling mythology. Steadily, as Wikipedia also became a persistent fixture in my online media diet, I found myself using the site in a similar manner, often going down “Wikipedia holes” wherein I bounced from page to page, topic to topic, probing for knowledge of topics both familiar and obscure. This newfound ability to find, consume, and interact with a universe of ideas previously diffuse among various types of sources and institutions made me feel empowered to more readily self- direct my intellectual interests. -

Understanding Formal and Informal Relationships in Settlement

Understanding formal and informal relationships in settlement upgrading for planning just and inclusive cities: the case of Phnom Penh, Cambodia Johanna Brugman Alvarez Master of Science in Urban Development Planning Bachelor of Urban and Regional Planning with Honours A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2019 School of Earth and Environmental Sciences Abstract Since colonial times a formal/informal divide entrenched in systems of urban planning in Phnom Penh, Cambodia has been used as a governmental tool by the state to marginalize and exclude informal settlements. This tool has also been used to impose a market-oriented model of urban development that is insufficient in progressing the aspirations, needs, and claims to justice of people living in these settlements. In fact, this model has led to the development of a highly unequal and unjust city. This problematic touches on a key aspect of planning knowledge which affects many other cities of the global south. Binaries are a characteristic of western thought and capitalism. This way of thinking reproduces a hierarchical worldview with a privileging pole and unequal power relationships by making divisions between formal/informal sectors, public/private property, ordinary/global cities, and individual/collective ways of life. Binaries turn the merely different into an absolute other and exclude and marginalize the reality of difference in cities. Despite growing evidence of formal and informal relationships in cities, most research has tended to concentrate on understanding these systems separately. My research addresses this knowledge gap. In this thesis I explain how formal and informal relationships are composed in the context of informal settlement upgrading practices in Phnom Penh with emphasis in three dimensions: a) land access, b) finance for housing, infrastructure and livelihoods, and c) political recognition. -

The Bullwhip Squadron News ______

3rd/17th --- 1st/9th Air Cavalry Squadron THE BULLWHIP SQUADRON NEWS _______________________________________________________________________ The official News Magazine of the Bullwhip Squadron Association September 2003 THE CAVALRYMAN You may ask, "Whence came this man?" Broad shouldered, with a weathered face. Mounted and weaponed, looking not just ahead, But with perception into even the next decade of man. He has come from the heartland of a nation To accept the burden of war. From the rich and poor, The arrogant rabble and idealist alike, Have come the cross section of his breed. For him, the torturous trail and endless thirst, Fear of death and bitter loneliness. The broken bodies of comrades lost to soon are assuaged Only by the fleeting emotion of brilliant victory! He has carved his hallmark on liberty and in so doing, Cast a long shadow over tyranny. Freedom shall have its way whenever he stands. By the sinew of his body And the spirit of his being, He has forged the assurance of a tomorrow. You and all mankind already know him. His deeds far excel the best efforts of man Forever accepting his nations challenge, This proud warrior moves, always to the vanguard. He is...The Cavalryman. By Lt. Col. Robert Drudik from "FIRST TEAM" FALL 1970 2 INDEX Item Page Poem 2 Adjutants Call 4 Taps 5 Eulogy, Richard Marshall 6 From the Commander 7 From the Command Sergeant Major 7 From the Chaplain 8 From the Sergeant Major 9 From the Vice President 10 2004 Reunion 11 From the Public Affairs Officer 11 Keeper of the Rock 12 The 9th Cav’s SABER Column 13 Julie 15 From The Swamp 18 Smoky 20 Legally Speaking 20 Military News 26 Health 29 Sick Call 33 Articles 33 Veterans Sound Off 38 Letters to the Editor 48 Lost and Found 50 Updates 50 Quartermaster Corner (Items For Sale) 51 Association Members 52 Advertisements 55 3 Adjutants Call ATTENTION TO ORDERS: "THANKS FOR THE MEMORIES". -

Superior Court of the District of Columbia Civil Division

SUPERIOR COURT OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIVIL DIVISION FRATERNAL ORDER OF POLICE, METROPOLITAN POLICE DEPART- MENT LABOR COMMITTEE, D.C. PO- LICE UNION, Case No. 2020 CA 003492B Plaintiff, (Hon. William M. Jackson) v. THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA, et al., Defendants. BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW, PUBLIC DEFENDER SERVICE FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA, AMERI- CAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA, WASHINGTON LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS AND URBAN AFFAIRS, AND LAW4BLACKLIVES DC IN SUPPORT OF DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA’S MOTION TO DISMISS In enacting the Comprehensive Policing and Justice Reform Amendment Act of 2020 (the “Act”), the District’s elected officials embraced increased accountability and transparency for a city with a troubled history of police abuses and chronic failures to hold officers responsible for their misconduct, particularly when that misconduct affects communities of color. The Council’s enactment of the Act reflects a violent reality: Interactions between the police and communities of color are more frequent, more dangerous, and more deadly than interactions between police and white residents. Here in the District, while there is little difference in rates of drug use, there are significant disparities between white and Black people in drug arrests: almost 9 out of 10 arrests for drug possession are of Black people.1 For young men, police violence is a leading cause of 1 See report prepared by amicus Washington Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights and Urban Affairs, Racial Disparities in Arrests in the District of Columbia, 2009-2011, at 2-3 (Jul. 2013), https://www.washlaw.org/pdf/wlc_report_racial_disparities.pdf.