The University-Innovation Nexus in Singapore. Go8 Backgrounder 28

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Facts & Figures 2018/19

Technical University of Munich Facts & Figures 2018/19 Microscopic examination in cancer research The Entrepreneurial University The Technical University of Munich (TUM) ranks among Europe’s most outstanding universities in research and innovation – an achievement powered by its distinctive character as “Entrepreneurial University”: Science beyond boundaries. TUM’s broad spectrum of subjects is unmatched across Europe, spanning engineering, the natural and life sciences, medicine, economics and social sciences. The university leverages this enormous potential by intensively and intelligently lin- king the different disciplines. In doing so, it successfully develops new fields of research extending from bioengineering to artificial intelli- gence. Simultaneously, it addresses the social, ethical and economic issues raised by technological change. Research meets practice. Doing research with the brightest minds in science, steering international projects and gaining early business experience: Students at TUM are perfectly prepared for working on the important topics of our time. That is why employers regularly nominate TUM as one of the top ten universities in the world. Opportunities for talent. TUM offers amazing opportunities at every level of study and research, starting with the first semester right through to professorship. It invests more than other universities in the professional development of individual talent. From lab to market. No other German university produces as many start-up founders as TUM, thanks to its unrivalled support -

To Download the Postgraduate Fair 2017

48 Course Sum- executive education guide POSTGRADUATE FAIR 2017 MBA AND MASTERS 9 SEP 2017, SAT Raffles City Convention Centre 47 INSTITUTIONS 36 INFO SESSIONS FREE ADMISSION What is the Postgraduate Fair? Event Format The Postgraduate Fair 2017 helps Professionals, u 36 Info Sessions (Masters & MBA) Managers and Executives explore postgraduate u 47 Education Institutions with over 80 courses courses that can help bring their careers to the next level. Explore MBA and Masters courses that are offered by local and Event Information international institutions. Speak with 47 Venue: Raffles City Convention Centre - Collyer Ballroom leading institutions and choose from Date: 9 Sep 2017 (Sat) / Time : 11:00am to 5:00pm 36 information sessions to gain insights Entry: Free Admission (Registration is required for entry) into the different programmes available. Register at www.Postgrad.com.sg Print Specifications – Full Colour Corporate Identity 29 08 08 IAL Participating Institutions Corporate Identity Management Development Instute of Singapore In Partnership GMATZ NE Technical University of Munich Asia ORGANISED BY Register now at www.Postgrad.com.sg 42HEADHUNT POSTGRADUATE FAIR 2017 \ MBA AND MASTERS executive HEADHUNT POSTGRADUATE FAIR 2017 \ MBA AND MASTERS education guide AVENTIS SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT CPE Reg. No. – 200700458M | Reg. Period - 20/05/2014 to 19/05/2018 JAMES COOK UNIVERSITY CPE Registration No. 200100786K | Period of Registration- 13 July 2014 to 12 July 2018 University of Roehampton London Postgraduate Programmes (3:20pm – 3:40pm): Postgraduate Programmes (2:20pm – 2:40pm): • MBA • Graduate Certificate of Career Development • MSc International Management with Marketing • Graduate Diploma of Psychology • MSc International Management with HR Management • Masters of Guidance and Counselling • MA Integrative Counselling & Psychotherapy • Master of Psychology (Clinical) CUHK BUSINESS SCHOOL Postgraduate Programmes (4:00pm – 4:20pm): KAPLAN HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTE • MBA CPE Reg. -

Newsletter May 2018

May 2018 ACS (INTERNATIONAL) NEWSLETTER IN THIS ISSUE Dear Parents, Students and Friends • Staff News Last week we were able to recognise leadership giftings in many of our students at our annual • Term 3 Start Dates Student Leadership Investiture. We thanked the outgoing leaders for their sterling efforts, and National Service Talk invested the incoming leaders into their new roles. It was a significant, formal and memorable • ceremony for all who attended. • Student Leadership Investiture Developing student Leadership is a core goal of our school. Our vision statement is to develop • PSP News future leaders with moral character, intellectual ability, international mindedness and deep compassion for humanity based upon Christian belief and values. • American Protege International Vocal At the Investiture students were advised that leadership takes many forms. There is no one Competition right way. The trailer of the movie, the Darkest Hour, starring Gary Oldman, who recently won an Academy Award for Best Actor for his portrayal of Winston Churchill, was shown to • Sermaine Saw – LCM High Distinction illustrate a few leadership points. Churchill is generally regarded as a great war time leader. th Churchill though was not perfect, a heavier drinker, not very approachable nor well liked, and • 10 ASEAN Schools Games had previous failed military campaigns in World War I; but World War II was his time – the • TKK Charity ProJect phrase ‘cometh the hour, cometh the man’ applies to Churchill at that dire time in British history. • Higher Education Fair Three key points were singled out from Churchill’s leadership. Firstly, you don’t have to be • Careers Week perfect to be a successful leader – Churchill certainly wasn’t – and similarly in our context, we do not expect our student leaders to be perfect, nor the most popular people in the school. -

Specialised Master Programmes Feature PG 21

HeadHunt Supplement - September 2019 Specialised Master Programmes Feature PG 21 UNIVERSITY COURSE SUMMARY Postgraduate Scholarship – Snapshot PG 44 - 54 PG 10-11 POSTGRADUATE FAIR 2O19 MBA, MASTERS, PhD & CE RAFFLES CITY CONVENTION CENTRE | 7 SEPT 2019, SAT 58 INSTITUTIONS 42 INFO SESSIONS FREE ADMISSION MICA (P) 022/06/2019 executive 2 Singapore Institute of Technology education guide executive education guide NUS Business School 3 executive 4 Singapore University of Technology and Design education guide EMPOWERING OUR STUDENTS TO BE FUTURE INNOVATORS, DESIGNERS AND LEADERS. CHOOSE SUTD MULTIDISCIPLINARY GRADUATE PROGRAMMES TODAY. PROGRAMMES ENQUIRIES - Master of Innovation by Design (New!) [email protected] - Master of Engineering (Research) https://sutd.edu.sg/Admissions/Graduate - Master of Science in Security by Design - Master of Science in Urban Science, Policy and Planning - SUTD-CGU Dual Masters in Nano- Electronic Engineering and Design - Engineering Doctorate - PhD Programme - SUTD-NUS Joint PhD Programme A BETTER WORLD BY DESIGN. executiLKCSB_EEGve Headstart_FPFC_200wx280h_Aug.pdf 1 2/7/19 10:02 AM education guide Singapore Management University 5 THE NEW ECONOMY NEEDS A NEW WAY OF THINKING. MASTERS LEE KONG CHIAN SCHOOL OF BUSINESS POSTGRADUATE PROGRAMMES EXECUTIVE MASTER OF MASTER OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN 22ND 43RD BUSINESS GLOBALLY1 BUSINESS GLOBALLY4 MANAGEMENT ADMINISTRATION ADMINISTRATION • Benefit from the collective experience of the • Gain industry experience working with real • Benefit from a Global-Asian Management most senior EMBA class profile in the world clients and budgets via the new Overseas Curriculum that covers the latest trends • Curriculum co-designed by 100 Immersion Programme (OIP) in business management senior executives and business • Enjoy lifelong ROI – • Flexible learning options to suit your needs. -

TUM. the ENTREPRENEURIAL UNIVERSITY. Innovation by Talents, Excellence, and Responsibility

Excellence Strategy of the Federal and State Governments Universities of Excellence Funding Line TUM. THE ENTREPRENEURIAL UNIVERSITY. Innovation by Talents, Excellence, and Responsibility Technical University of Munich Commencement of funding 1 November 2019 1 Overall Strategy for Funding in the Excellence Strategy of the Federal and State Governments TUM. THE ENTREPRENEURIAL UNIVERSITY. Innovation by Talents, Excellence, and Responsibility Technical University of Munich Munich, 6 December 2018 Place, date Wolfgang A. Herrmann, President 2 Brief profile of the university Established in: 1868 28 Academic structural units: a) 15 Departments: Aerospace & Geodesy (under formation) | Architecture | Chemistry | Civil, Geo and Environmental Engineering | Management | Education | Electrical and Computer Engineering | Informatics | Mathematics | Mechanical Engineering | Medicine | Nutrition, Land Use, and Environment (Weihenstephan) | Physics | Political Sciences/Governance | Sport and Health Sciences – b) 6 Integrative Research Centers: TUM Institute for Advanced Study | Munich Center for Technology in Society | Munich School of Engineering | Munich School of BioEngineering | Campus Straubing for Biotechnology and Sustainability | Munich School of Robotics and Machine Intelligence – c) 7 Corporate Research Centers: Center for Functional Protein Assemblies | TUM Catalysis Research Center | Research Neutron Source Heinz Maier- Leibnitz (FRM II) | TranslaTUM: Translational Research in Oncology | Walter Schottky Institute for Semiconductor Physics -

3-4 TUM Asia

Technical University of Munich in Singapore (TUM Asia) Technical University of Munich (TUM) Location Main campus of TUM located at the city centre of Munich University Ranking University in #1 Germany In Germany for Electrical #2 Engineering In 2017 Global Employability #8 Survey Worldwide in #14 Chemistry QS World University Rankings 2015 Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) The Global University Employability Ranking 2017 (Times Higher Education) TUM Facts And Figures 14 Departments 545 Professors 41,000 Students >60,000 Alumni 26% Intl Students Heinrich Wieland Thomas Mann Hans Fischer Rudolf Mößbauer Ernst Otto Fischer Chemistry (1927) Literature (1929) Chemistry (1930) Physics (1961) Chemistry (1973) 17 Nobel Prize Awardees Robert Huber Klaus von Klitzing Konrad E. Bloch Ernst Ruska J. Deisenhofer Chemistry (1988) Physics (1985) Medicine (1964 ) Physics (1986) Chemistry (1988) Wolfgang Paul Erwin Neher Rudolph Marcus Wolfgang Ketterle Gerhard Ertl Bernhard Feringa Joachim Frank Physics (1989) Medicine (1991) Chemistry (1992) Physics (2001) Chemistry (2007) Chemistry (2016) Chemistry (2017) Famous TUM Inventors Carl von Linde Refrigeration Rudolf Diesel Combustion Technology Energy Clause Dornier Aircraft Oskar von Miller Germany‘s 1st Technologies Power Station 3 Campuses in Munich Munich, Downtown Garching Freising, Weihenstephan A Research University Integrative Research Centres Corporate Research Centres • TUM Institute for Advanced Study • Research Neutron Source (FRM II) • Munich Centre for Technology in Society • Institute -

Internationalization of Tertiary Education Services in Singapore

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Toh, Mun-Heng Working Paper Internationalization of tertiary education services in Singapore ADBI Working Paper, No. 388 Provided in Cooperation with: Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), Tokyo Suggested Citation: Toh, Mun-Heng (2012) : Internationalization of tertiary education services in Singapore, ADBI Working Paper, No. 388, Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), Tokyo This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/101240 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu ADBI Working Paper Series Internationalization of Tertiary Education Services in Singapore Mun-Heng Toh No. 388 October 2012 Asian Development Bank Institute Mun-Heng Toh is associate professor at the Department of Strategy and Policy, National University of Singapore. -

Digi Presentation Andrea

The Centres for Global Health Munich/Oslo Center for Global Health (TUM) | Centre for Global Health (UiO) | 1 The University of Oslo • Founded in 1811 • 8 faculties & 2 museums • Strong track record of pioneering research & scientific discovery: 5 Nobel Prize winners • 8 National Centres of Excellence • Strategic focus on research in the field of energy & life sciences A non-profit research university, access to • 2016 for UiO good public funding schemes • Extensive EU research project portfolio - 28 000 students • 800 courses in English, 40 Master’s degree - 2954 PhD candidates programmes entirely in English & several PhD - 7000 staff programmes Center for Global Health (TUM) | Centre for Global Health (UiO) | 2 Faculty of Medicine Nationally Designated Research Centres: • Institute of Basic Medical Sciences Jebsen Foundation Research Centres • Institute of Clinical Medicine Cancer Stem Cell Innovation Centre • Institute of Health and Society Cardiac Research Centre Centre for Psychosis Research Key figures for the Medical Faculty for Centre for Vaccine Research 2016 Center for Cardiology Research Ø 2203 Registered students (1271 Centres of Excellence medical, 903 Master, 73% women) Centre for Molecular Biology and Ø 1325 PhD candidates Neuroscience (CMBN) Ø 190 PhDs graduating (63,7% women) Centre for Immune Regulation (CIR) Ø 1386 academic staff Centre for Cancer Biomedicine (CCB) Ø 190 Technical + 288 Admin staff Centre for Research Driven Innovation Ø 2233 Scientific publications Cancer - stem cell innovation center Ø 753 Active research -

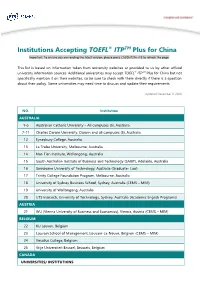

Institutions Accepting TOEFL® ITPTM Plus for China Important: to Ensure You Are Reading the Latest Version, Please Press Ctrl/Shift/Fn+F5 to Refresh the Page

Institutions Accepting TOEFL® ITPTM Plus for China Important: To ensure you are reading the latest version, please press Ctrl/Shift/Fn+F5 to refresh the page. This list is based on information taken from university websites or provided to us by other official university information sources. Additional universities may accept TOEFL® ITPTM Plus for China but not specifically mention it on their websites, so be sure to check with them directly if there is a question about their policy. Some universities may need time to discuss and update their requirements. Updated December 9, 2020 NO. Institution AUSTRALIA 1-6 Australian Catholic University – All campuses (6), Australia 7-11 Charles Darwin University, Darwin and all campuses (5), Australia 12 Eynesbury College, Australia 13 La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia 14 Nan Tien Institute, Wollongong, Australia 15 South Australian Institute of Business and Technology (SAIBT), Adelaide, Australia 16 Swinburne University of Technology, Australia (Graduate- Law) 17 Trinity College Foundation Program, Melbourne, Australia 18 University of Sydney Business School, Sydney, Australia (CEMS – MIM) 19 University of Wollongong, Australia 20 UTS Insearch, University of Technology, Sydney, Australia (Academic English Programs) AUSTRIA 21 WU (Vienna University of Business and Economics), Vienna, Austria (CEMS – MIM) BELGIUM 22 KU Leuven, Belgium 23 Louvain School of Management, Louvain-La-Neuve, Belgium (CEMS – MIM) 24 Vesalius College, Belgium 25 Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium CANADA UNIVERSITIES/ -

Postgraduate Fair

POSTGRADUATEMBA, MASTERS, PhD & CE FAIR ESSEC BUSINESS SCHOOL CPE Reg. No. – 200511927D | Reg. Period - 30/06/2017 to 29/06/2023 Postgraduate Programmes (3:40pm – 4:00 pm): AALTO EXECUTIVE EDUCATION ACADEMY • ESSEC & Mannheim Executive MBA Asia-Pacific CPE Reg. No – 200000295R | Period of Registration: 13/10/2010 – 12/10/2020 • Global MBA • Aalto-ESADE MBA for Executives • Master in Finance • Master in Management • MSc in Marketing Management & Digital • Advanced Master in Strategy & Management of International Business • Master in Data Sciences & Business Analytics AMITY GLOBAL INSTITUTE CPE Reg. No. – 200606974C | Reg. Period – 18/07/2019 to 17/07/2023 University of London • Master of Business Administration (with 5 Specialism) IE BUSINESS SCHOOL / IE UNIVERSITY University of Northampton Postgraduate Programme: • Master of Business Administration • International MBA University of Stirling • IE-SMU MBA • Master of Business Administration • Master in Finance • Master of Science Banking and Finance • Master in Business Analytics & Big Data • Master of Science Data Science for Business • Master in Digital Marketing INFOCOMM MEDIA DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY Information Session (3:20pm – 3:40pm): AVENTIS SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT • Singapore Digital (SG:D) Scholarship (Polytechnic) CPE Reg. No. – 200700458M | Reg. Period - 20/05/2019 to 19/05/2021 • Singapore Digital (SG:D) Scholarship (Undergraduate) Postgraduate Programmes (3:40pm – 4:00pm): • Singapore Digital (SG:D) Scholarship (Postgraduate) California State University • IT Management MBA | International Management MBA I Finance MBA University of Roehampton - London • Master of Business Administration • Master in Global Human Resources Management • Master in Global Marketing JAMBOREE EDUCATION • Master in Counselling & Psychotherapy • GMAT Aventis School of Management • GRE • Postgraduate Diploma in Business Administration • IELTS/ TOEFL • Admissions Counselling CPA AUSTRALIA Information Session (12:40pm – 1:00pm): JAMES COOK UNIVERSITY • CPA Program CPE Reg. -

Level up Your Future Today | 5 Sep 2020, Sat

HeadHunt Supplement - September 2020 UNIVERSITY COURSE SUMMARY PG 35 - 47 LEVEL UP YOUR FUTURE TODAY | 5 SEP 2020, SAT 37 INSTITUTIONS 41 INFO SESSIONS FREE VIRTUAL FAIR MCI (P) 068/06/2020 executive 2 education guide LEVEL UP YOUR FUTURE TODAY | 5 SEP 2020, SAT 37 INSTITUTIONS 41 INFO SESSIONS FREE VIRTUAL FAIR ZONE 1 ZONE 2 35 Chat Rooms 41 Zoom – Institutions Information Sessions UNIVERSITY Over 200+ MBA, Masters, PhD & Continuing Telegram Bot Education Courses Course Adviser ZONE 3 ZONE 4 executive education guide Infocomm Media Development Authority 3 Be supported by IMDA to pursue postgraduate studies in specialised infocomm media areas such as Cybersecurity, Immersive Media, Artificial Intelligence, Data Analytics and Digital Content Creation offered by local and overseas universities. executive 4 Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) education guide Empowering our students to be future innovators, designers and leaders of the world. Choose SUTD multidisciplinary graduate programmes today. OUR GRADUATE PROGRAMMES MASTER OF SCIENCE MASTER OF MASTER OF IN SECURITY INNOVATION ENGINEERING BY DESIGN BY DESIGN SINGAPORE SUTD-CGU DUAL MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF MASTER OF MASTERS IN IN URBAN SCIENCE, ARCHITECTURE NANO-ELECTRONIC POLICY AND PLANNING ENGINEERING & DESIGN TECHNOLOGY ENGINEERING SUTD-NUS JOINT PhD PROGRAMME DOCTORATE PhD AND DESIGN PROGRAMME A BETTER WORLD BY DESIGN. "Joining SUTD's PhD programme has "Being the first EDB-IPP student with allowed me to pursue cross-disciplinary NVIDIA has also exposed me -

Technische Universität München 2 TUM – University of Excellence Contents

Technische Universität München 2 TUM – University of Excellence Contents TUM Research and Teaching TUM: A global brand 6 TUM Faculties 10 Interdisciplinary horizons 18 TUM University Foundation 20 TUM People Faces 22 Nobel Prize winners 30 Inventors and discoverers 31 Discovering talent, promoting talent, using talent 32 Alumni 34 TUM Excellence Research Centers 38 Cutting-edge research 52 Collaborative Research Centers Transregional Collaborative Research Centers 56 TUM Environment and Locations International 60 Munich – the business capital 62 Munich – Garching – Weihenstephan: TUM 3 64 Culture and leisure 68 Contacts 70 Imprint 72 TUM – University of Excellence 3 Scientific, entrepreneurial, international Ever since its inception in 1868, the Technische Universität München has borne out what, since the time of Humboldt, has epitomized the idea of the university – education and training as scientific objective – research as fascination, adventure, character building and societal culture. Eminent figures have studied, taught and conducted research here – Nobel Prize winners, inventors, entrepreneurs, representatives of public life But we can thank a strong community spirit that knows no boundaries between the generations and nurtures performance for its rise to become a world-class university The most visible proof of the strength of the TUM family is the rebuilding of our university from the ruins of a world war that had virtually destroyed it Today, around 26,000 young people study here – 23 percent of them from abroad – in the 13 faculties