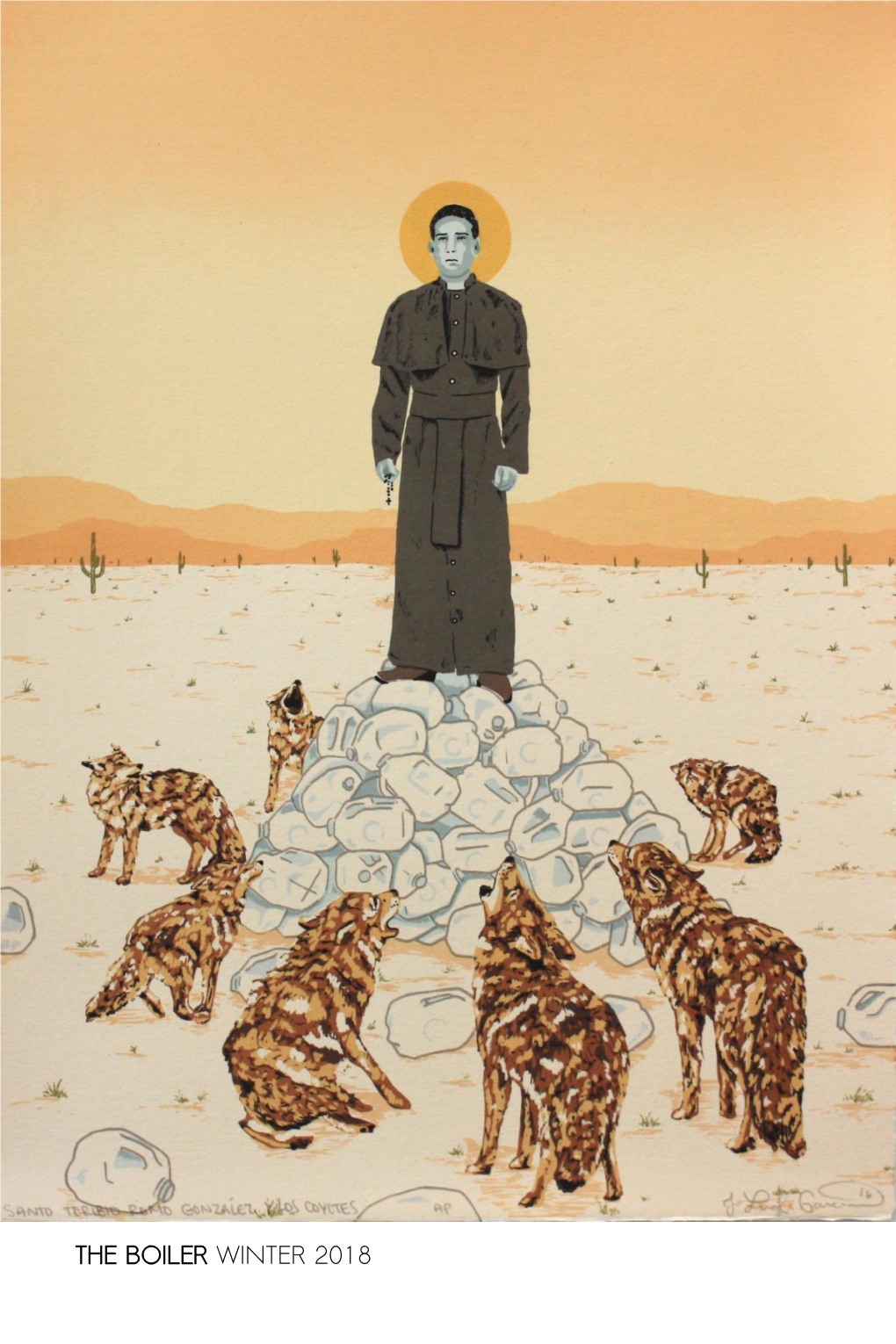

The Boiler Winter 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 6-2005 The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos Ladel Lewis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Lewis, Ladel, "The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos" (2005). Master's Theses. 4192. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4192 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PORTRAYAL OF AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN IN HIP-HOP VIDEOS By Ladel Lewis A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 2005 Copyright by Ladel Lewis 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thankmy advisor, Dr. Zoann Snyder, forthe guidance and the patience she has rendered. Although she had a course reduction forthe Spring 2005 semester, and incurred some minor setbacks, she put in overtime in assisting me get my thesis finished. I appreciate the immediate feedback, interest and sincere dedication to my project. You are the best Dr. Snyder! I would also like to thank my committee members, Dr. Douglas Davison, Dr. Charles Crawford and honorary committee member Dr. David Hartman fortheir insightful suggestions. They always lent me an ear, whether it was fora new joke or about anything. -

Heather Hayes Experience Songlist Aretha Franklin Chain of Fools

Heather Hayes Experience Songlist Aretha Franklin Chain of Fools Respect Ben E. King Stand By Me Drifters Under The Boardwalk Eddie Floyd Knock On Wood The Four Tops Sugar Pie Honey Bunch James Brown I Feel Good Sex Machine The Marvelettes My Guy Marvin Gaye & Tammie Terrell You’re All I Need Michael Jackson I’ll Be There Otis Redding Sittin’ On The Dock Of The Bay Percy Sledge When A Man Loves A Woman Sam & Dave Soul Man Sam Cooke Chain Gang Twistin’ Smokey Robinson Cruisin The Tams Be Young, Be Foolish, Be Happy The Temptations OtherBrother Entertainment, Inc. – Engagement Contract Page 1 of 2 Imagination My Girl The Isley Brothers Shout Wilson Pickett Mustang Sally Contemporary and Dance 50 cent Candy Shop In Da Club Alicia Keys If I Ain’t Got You No One Amy Winehouse Rehab Ashanti Only You Ooh Baby Babyface Whip Appeal Beyoncé Baby Boy Irreplaceable Naughty Girls Work It Out Check Up On It Crazy In Love Dejá vu Black Eyed Peas My Humps Black Street No Diggity Chingy Right Thurr Ciara 1 2 Step Goodies Oh OtherBrother Entertainment, Inc. – Engagement Contract Page 2 of 2 Destiny’s Child Bootylicious Independent Women Loose My Breath Say My Name Soldiers Dougie Fresh Mix Planet Rock Dr Dre & Tupac California Love Duffle Mercy Fat Joe Lean Back Fergie Glamorous Field Mobb & Ciara So What Flo Rida Low Gnarls Barkley Crazy Gwen Stefani Holla Back Girl Ice Cube Today Was A Good Day Jamie Foxx Unpredictable Jay Z Give It To Me Jill Scott Is It The Way John Mayer Your Body Is A Wonderland Kanye West Flashy Lights OtherBrother Entertainment, Inc. -

Dj Whoo Jae Millz Dj Vlad

BACK 2 SCHOOL FASHIONS MIXTAPE REVIEWS COLLECTOR’S EDITION Re-Defining The Mixtape Game DJ WHOO KIDG-UNIT’S GENERAL ADDS $TREET VALUE TO THE GAME JAE MILLZ PLUS: POPS OFF A CONRAD DIMANCHE XAVIER AEON MILLION ROUNDS HAWK VOLUME 1 ISSUE 2 DJ VLAD THE BUTCHER CUTS IT UP >DJ WHOO KID On the cover and this page: (“Street Value” Pg. 44) Photographed Exclusively for Mixtape Magazine by RON WEXLER FEATURES CONTENT VOL.1 ISSUE 2 44 DJ WHOO KID $TREET VALUE G-Unit General or G-Unit Soldier? Crown the kid king if you call him anything. DJ Whoo Kid in his most upfront story to date alerts the game about his strategy and formula for worldwide, not just domestic success. By Kay Konnect 70 Xavier Aeon 74 DJ VLAD 80 Jae Millz THE BUTCHER Rhythm and Blues new Mix it up. Blend it up. Jae Millz, the lyrical sharp- boy wonder from the CT, Whatever you do, make shooter steps to the streets Connecticut to be exact, sure to cut it up. DJ Vlad in a Mixtape Magazine explains in an uncut manner “The Butcher” slices the exclusive. He drops bullets the difference between a mixtape game in half with regarding his demeanor and typical artist and one with exclusive compilations from operation in the mixtape rap an edge. Shaken with a the east-south-mid-west. world. Ready as ever, Jae Hip Hop feel, Xavier Aeon DJ Vlad’s story plugs the Millz pops off a million exposes his sharpness. world to his sword-like rounds easily. -

He's Been Fighting for His Career for Near Fifteen Years. Never Afraid of Change, He's Sticking and Moving and Going For

! Ü HE’S BEEN FIGHTING FOR HIS CAREER FOR NEAR FIFTEEN YEARS. NEVER AFRAID OF CHANGE, HE’S STICKING AND MOVING " AND GOING FOR HIS. BUT TIME WEARS HARD ON THE BOOGIE DOWN STREETS. HAS HAD HIS HITS, BUT HE’S TAKEN SOME, TOO. SALTER S JEFFERY // IMAGE GOLIANOPOULOS THOMAS WORDS Ü " ! XXL MAGAZINE 000 ! Ü " " t’s seven o’clock in the evening, album past 500,000 in sales, earning him his and recent audience-expanding cameos with and Fat Joe needs a designated first gold plaque. Three years later, in 2001, Jennifer Lopez, Paris Hilton and Ricky Martin, driver. The 36-year-old rapper isn’t when Murder Inc. was dominating hip-hop he J.O.S.E. remains his only platinum record. inebriated, but he drives like Ricky released “What’s Luv?” a frothy Irv Gotti pro- Joe is well aware of his SoundScan struggles. Bobby after one too many Miller duction that propelled Jealous Ones Still Envy “The strangest thing in the whole universe,” Lites. He breaks too suddenly, ac- to platinum status. Today, the South runs hip- he says, “is Fat Joe being a household name, celerates too carelessly and nearly hop, and, of course, Fat Joe has noticed. making the biggest hit records in the history of crashes too often. He’s also eas- “Joe’s good at reading the future,” says mankind, and not selling that many records. It ily distracted by the radio (Nelly Miami-based DJ Khaled, who’s known him for will be reevaluated years from now.” Furtado’s “Promiscuous” brings more than 10 years. -

Fat Joe Lean Back

Lean Back Fat Joe Owwwu! Yeah! My niggaz! Uh-huh! Throw ya hands in 'da air right now, man! Feel 'dis shit right here! Scott Storch nigga! Yeah Khalid, I see you, nigga! Show Big-Pun love! Uh! Yeah! Uh! Yo! I don't give a fuck about'cha faults, or mishappenins, nigga. We from Da Bronx, New York... Shit happens. Kids clappin, luv ta spark da place. Half da niggaz in 'da squad got a scar on dey face. It's a cold world, and dis is ice. Half a mill' for da charm, nigga, dis is life. Got 'da Phantom in front of da buildin, Trinity Ave. Ten years been legit, dey still figure me bad. As a youngin, I was too much to cope with. Why you think, mo'fuckers nick-named me "Cook Coke" shit. Should'a been called Don Robbery, Extortion, or maybe Grand Larceny. I did it all, I put 'da pieces to da puzzle. Just as long, I knew me and my peoplez was gonna' bubble. Came out da gate on some Flow-Joe shit. Fat nigga with da shotty was "The Logo Kid". Said my niggaz dont dance, We just pull up our pants and, Do da Roc-away. Now lean back, lean back, lean back, lean back. I said my niggaz don't dance, We just pull up our pants and, Do 'da Roc-away. Now lean back, lean back, lean back, lean back. (Come on!) R to the E'zzie', M to the whiz-zY, My arms stay breezy, The Don stays fizz-zY, Got a date at 8, I’m in the 740'fizz-ive, And I just bought a bike, so I can ride till I die, Wit' a matchin' jacket, Bout' to cop me a mansion, My niggas in 'da club, but you know 'dey not dancin'. -

Appendix E – Seat Prototypes

APPENDIX E Seat Prototypes: Public Outreach Fleet of the Future Seat Prototype Survey Tell BART what you think, and enter to win a $100 Clipper card! Thank you for visiting BART’s seat prototypes today. Please take a few moments to try Seat Options A, B, and C. The bottom seat cushions on Seats A, B, and C differ slightly, and we want to know what you think. You can also enter to win a $100 Clipper card! (Details on back.) 1. Seat Options How do you rate each seat option in terms of comfort? Please check “Excellent,” “Good,” “Only Fair,” or “Poor” for each option below. Then tell us why you rated each seat this way. If you did not try a particular seat, please check “Don’t Know.” SEAT RATING REASON FOR RATING Seat Option A Excellent Good Only Fair Poor Don’t Know Seat Option B Excellent Good Only Fair Poor Don’t Know Seat Option C Excellent Good Only Fair Poor Don’t Know 2. After you have tried each seat option, please answer this question: which seat do you prefer for the new BART train cars? (Check only one.) Seat Option A Seat Option B Seat Option C No preference None of the above 3. For each of the seat options shown today, the seats in the back row have a center armrest. Which of the following do you prefer for the new train cars? (Check only one.) Armrests between all seats Armrests between some seats No armrests between seats No preference 4. Do you have any other comments about the seats for the new train cars? _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Printed on recycled paper OVER Please tell us about yourself. -

Fly - Swag Surfin Free Mp3 Download Swag Surfing Mp3

fly - swag surfin free mp3 download Swag Surfing Mp3. We have collected a lot of useful information about Swag Surfing Mp3 . The links below you will find everything there is to know about Swag Surfing Mp3 on the Internet. Also on our site you will find a lot of other information about kitesurfing, wakeboarding, SUP and the like. Swag Surfin' (Explicit) - YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kf5QZ-WUGKo Jul 29, 2018 · Provided to YouTube by Universal Music Group Swag Surfin' (Explicit) · F.L.Y. (Fast Life Yungstaz) Jamboree ℗ 2009 The Island Def Jam Music Group Released on: 2009-01-01 Producer: Kevin "KE on . Author: FLYISDALIMIT. FLY – Swag Surfin Free Mp3 Download & Listen Online MP3GOO. https://imp3goo.co/download/fly-swag-surfin/ Free Download FLY – Swag Surfin Mp3. We have 20 mp3 files ready to listen and download. To start the download you need to click on the [Download] button. We recommend the first song named FLY - Swag Surfin HQ.mp3 with a quality of 320 kbps. F.L.Y. - Swag Surfin' [Prod. By K.E. On The Track] mp3 . https://www.livemixtapes.com/download/mp3/202862/fly_swag_surfin_prod_by_ke_on_the_track.html F.L.Y. Swag Surfin' [Prod. By K.E. On The Track] free mp3 download and stream. Swag Surfin - Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swag_Surfin "Swag Surfin" is the debut single by American hip hop group Fast Life Yungstaz. It is featured on their debut album Jamboree and is produced by K.E. on the Track.. It is the unofficial anthem of the WNBA's Washington Mystics and was played at the game in which the team won its first championship.Genre: Trap, pop rap. -

Canadian Hybrid Tournament 2017 Packet M.Txt- Written by Tossups

Canadian Hybrid Tournament 2017 Packet M.txt- Written by Tossups 1. In one of this character’s appearances, they ask “What use is being cool if you can’t wear a sombrero?” In another appearance, while this character is hanging from a tree and eating a tuna sandwich, they say “we’re kind of stupid that way.” This character also informs a friend that the measurement of a peck is a quick smooch, making their friend question their (*) math homework. On one of the covers of the works that this character appears in, they are piloting a red wagon into a pond with their friend being towed behind with an umbrella. On another cover of a work featuring this character, they tackle their friend as their friend comes home from school. This character “betrays” their friend by playing with Susie Derkins. For 10 points, name this Bill Watterson character, a stuffed tiger who hangs out with Calvin. ANSWER: Hobbes (do not accept or prompt on “Thomas Hobbes”) 2. In this work, a striped tie is removed from a striped box worn around the neck of a man who bicycles while wearing a nun’s habit. An androgynous woman is given that striped box by a policeman after poking a severed hand with a cane in this work. In this work a man attempts to reach a woman in the corner of an apartment while pulling (*) ropes connected to two pumpkins, two stone tablets, two pianos with dead donkeys inside them, and two priests. It’s not Silence of the Lambs, but a woman enters an apartment to see a death’s-head moth in this work, and ants spill out of a man’s hand on two occasions in this film. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Swoon: The Art of Sinking Naomi Booth PhD, Creative and Critical Writing University of Sussex March 2014 1 Acknowledgements My greatest thanks go to my supervisor, Professor Nicholas Royle, for his generous and insightful criticism, and for his support and inspiration throughout the writing of this thesis. I am extremely grateful to readers of various chapters of this work, in particular Dr Catherine Packham and Dr Katie Walter. I am also grateful to Dr Abi Curtis for her encouragement and support at the beginning of this project. The suggestions of various creative readers of the creative part of this thesis have been extremely useful; these readers include Thomas Bunstead, Kieran Devaney, Helen Jukes, Kate Murray-Browne and Toby Smart. Dulcie Few has been an insightful and generous reader, and conversations with her have often galvanised me during the development of this work. I am indebted to Thomas Houlton and Laura Ellen Joyce, extremely generous and thorough readers whose ready conversation and creative suggestions have helped me enormously. -

Top 200 Party Songs

TOP 200 PARTY SONGS HEY YA! OUTKAST HERO ENRIQUE IGLESIAS BEAUTIFUL CHRISTINA AGUILERA CHA-CHA SLIDE MR. C THE SLIDE MAN CHICKEN DANCE VARIOUS SMOOTH SANTANA YEAH USHER BABY BOY BEYONCE W/ SEAN PAUL COME ON EILEEN DEXY’S MIDNIGHT RUNNERS GET LOW LIL’ JON & THE EAST SIDE BOYZ PICTURE KID ROCK & SHERYL CROW DIP IT LOW CHRISTINA MILIAN AMAZED LONESTAR MY PLACE NELLY W/ JAHEIM KETCHUP SONG LAS KETCHUP IN DA CLUB 50 CENT COULD I HAVE THIS DANCE ANNE MURRAY WHEN THE SUN GOES DOWN KENNY CHESNEY HOT IN HERRE NELLY LIVIN’ ON A PRAYER BON JOVI MY MARIA BROOKS & DUNN ELECTRIC BOOGIE (SLIDE) MARCIA GRIFFITHS I HOPE YOU DANCE LEE ANN WOMACK BUTTERFLY KISSES BOB CARLISLE BABY GOT BACK SIR MIX-A-LOT RIDE WIT ME NELLY KEEPER OF THE STARS TRACY BYRD YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG AC/DC BILLIE JEAN MICHAEL JACKSON HOLLA BACK MARIO YMCA VILLAGE PEOPLE BEER FOR MY HORSES TOBY KEITH BUILD ME UP BUTTERCUP FOUNDATIONS BROWN EYED GIRL VAN MORRISON EVERY TIME BRITNEY SPEARS HELLA GOOD NO DOUBT OLD TIME ROCK ‘N’ ROLL BOB SEGER LOSE YOURSELF EMINEM I WANNA TALK ABOUT ME TOBY KEITH SHAKE YA TAILFEATHER MURPHY LEE WHEN YOU SAY NOTHING AT ALL ALISON KRAUSS LET’S GET DOWN BOW WOW FRIENDS IN LOW PLACES GARTH BROOKS LAST DANCE DONNA SUMMER JUMP AROUND HOUSE OF PAIN WONDERFUL TONIGHT ERIC CLAPTON I SAW HER STANDING THERE BEATLES VIBRATE PETEY PABLO LOVE SHACK B-52’S NEW YORK, NEW YORK FRANK SINATRA SUGA SUGA BABY BASH W/ FRANKIE J. -

'Fore She Was Mama -‐ Walker, Clay 1, 2 Step -‐ Ciara & Missy El

'Fore She Was Mama - Walker, Clay 1, 2 Step - Ciara & Missy Elliott 10 CC - Donna 10 CC - Dreadlock Holiday 10 CC - I'm Mandy 10 CC - I'm Not In Love 10 CC - Rubber Bullets 10 CC - The Things We Do For Love 10 CC - Wall Street Shuffle 10 Years - Through The Iris 10 Years - Wasteland 10 Years After - I'd Love To Change The World 10,000 maniacs - like the weather 10,000 Maniacs - More Than This 10.000 Maniacs - These Are The Days 100% Cowboy - Jason Meadows 101 Dalmatians - Cruella De Ville 112 - Cupid 112 - Dance With Me 112 - It's Over Now 112 - Only you 112 - Peaches & Cream 112 - U Already Know 12 Gauge - Dunkie Butt 1234 - Feist 15 Minutes - Atkins, Rodney 1910 Fruitgum Co - Simon Says 1910 Fruitgum Company - Simon Says.avi 1973_-_Blunt,_James 1st Time - Yung Joc Marques Houston Trey Songz 2 Become One 2 D Extreme - If I knew then 2 Live Crew - Do wah diddy 2 Live Crew - We Want Some Pussy 2 Pac - Thugz Mansion 2 Pac - Until the end of time 2 Play & Thomas Jules & Jucxi D - Careless Whisper 2 Step - DJ Unk 2 Unlimited - No Limits 20 Fingers - Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls - 21st Century Girls 26 Cents - The Wilkinsons 2O - Rapture 2O - Rapture tastes so sweet 3 Days Grace - Never Too Late 3 Degrees, The - Woman In Love 3 Doors Down - Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down - Be Like That 3 Doors Down - Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down - Duck & Run 3 Doors Down - Here Without You 3 Doors Down - Kryptonite 3 Doors Down - Landing In London 3 Doors Down - Let Me Go 3 Doors Down - Live For Today 3 Doors Down - Loser 3 Doors Down - Road I'm On 3 Doors Down - When I'm Gone 3 Of Hearts - Arizona Rain 3 Of Hearts - Love is enough 30 Seconds To Mars - Kill, The 30 Seconds To Mars - Kings & Queens 311 - All Mixed Up 311 - Don't Tread On Me 311 - First Straw 311 - Love Song 311 - You wouldn't believe 35L - Take It Easy 38 Special - Teacher, Teacher 3LW - No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3oh!3 & Ke$ha - My First Kiss 3oh!3_-_dont_trust_me 3T - Anything 3T - Tease me 4 In The Morning - Gwen Stefani 4 Non Blondes - What's Up 4 p.m. -

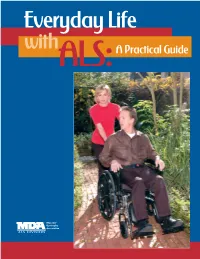

Everyday Life with ALS: a Practical Guide

Everyday Life with ALS: A Practical Guide Everyday Life with ALS: A Practical Guide Published and distributed by the MDA ALS Division MDA Publications Department © 2005, 2010 Muscular Dystrophy Association Inc. Everyday Life with ALS: A Practical Guide 3 Everyday Life with ALS: A Practical Guide Published by MDA ALS Division 3300 E. Sunrise Drive Tucson, AZ 85718 R. Rodney Howell, M.D., Chairman of the Board Gerald C. Weinberg, President & CEO als.mda.org Copyright © 2005, 2010 Muscular Dystrophy Association Inc. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, excepting brief quotes used in connection with reviews written specifically for inclusion in a magazine or newspaper. Free to families of those with ALS who are registered with MDA. $15 for others and $20 for international orders (includes Canada). Contact [email protected]. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book is a revision and expan- experts who work with MDA/ALS centers sion of ALS: Maintaining Mobility, was also invaluable. We’re deeply grate- A Guide to Physical Therapy and ful to: Jeff Edmiaston, M.S., CCC-SLP Occupational Therapy, which was pub- (speech-language pathologist), Barnes lished by the MDA/ALS Center at Baylor Jewish Hospital Rehab Department, College of Medicine in Houston and St. Louis; Lyn Goldsmith, R.N., B.S.N., MDA in the early 1980s. The authors clinical research nurse/coordinator, were the late Vicki Appel, R.N., ALS Department of Neurology, Eleanor and Clinic Coordinator, along with Melinda Lou Gehrig MDA/ALS Research Center, Callendar, physical therapist, and Susan Columbia University Medical Center, New Sunter, occupational therapist.