P the Party 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the United States District Court for the District Of

Case 1:04-cv-00611-ACK-LK Document 68 Filed 02/07/08 Page 1 of 28 PageID #: <pageID> IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF HAWAII RALPH NADER, PETER MIGUEL ) CIVIL NO. 04-00611 JMS/LEK CAMEJO, ROBERT H. STIVER, ) MICHAEL A. PEROUTKA, CHUCK ) ORDER (1) GRANTING IN PART BALDWIN, and DAVID W. ) AND DENYING IN PART PORTER, ) DEFENDANT’S MOTION TO ) DISMISS OR IN THE Plaintiffs, ) ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY ) JUDGMENT; AND (2) DENYING vs. ) PLAINTIFFS’ CROSS-MOTION ) FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT KEVIN B. CRONIN, Chief Election ) Officer, State of Hawaii, ) ) Defendant. ) ______________________________ ) ORDER (1) GRANTING IN PART AND DENYING IN PART DEFENDANT’S MOTION TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT; AND (2) DENYING PLAINTIFFS’ CROSS-MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT I. INTRODUCTION Plaintiffs sought inclusion on the Hawaii general election ballot as independent candidates for president and vice-president in the 2004 election, but were denied ballot access because Dwayne Yoshina, former Chief Election Officer for the State of Hawaii, 1 determined that they had not obtained the required 1 Yoshina retired as the Chief Election Officer on March 1, 2007. Office of Elections employee Rex Quedilla served as the Interim Chief Election Officer until the State of Hawaii Election Commission appointed Kevin B. Cronin as the Chief Election officer effective February (continued...) Case 1:04-cv-00611-ACK-LK Document 68 Filed 02/07/08 Page 2 of 28 PageID #: <pageID> number of petition signatures for inclusion on the ballot. Plaintiffs challenged the procedures used in reviewing the petition signatures in both state and federal court. -

Dobbs on Truckers Strike Rebecca Finch, New York Socialist Workers Party Candi in New York City

FEBRUARY 22, 1974 25 CENTS VOLUME 38,1NUMBER 7 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE On-the-scene rel}orts Minnesota truckers vote Feb. 10 to continue strike. Reporters for the Militant aHended strike meetings around the country. For their reports, and special feature on Teamsters union and independent truckers in 1930s and today, see pages 5-9. riti m1ners• ae eat In Brief BERRIGAN REFUSED JOB AT ITHACA: 300 angry prisoners labeled "special offenders." students confronted Ithaca College President Henry Phillips Delegations from Rhode Island, Maine, and Connecti Feb. 7, demanding to know why the college withdrew an cut attended the rally, which was very spirited, despite offer of a visiting professorship to Father Daniel Berrigan. a heavy snowstorm. Speakers at the rally included Richard THIS The college made the offer last December and President Shapiro, executive director of the Prisoners Rights Project; Phillips withdrew it one month later without consulting Russell Carmichael of the New England Prisoners Associa students and faculty. tion; State Representative William Owens; and Jeanne Laf WEEK'S This was the second meeting called by students since ferty, Socialist Workers Party candidate for attorney gen a petition signed by 1,000 students failed to elicit a eral of Massachusetts. MILITANT response from the administration. The students are pro testing the arbitrary decision and demanding a full ex PUERTO RICAN POETRY FESTIVAL PLANNED: The 3 Union organizers speak planation for the withdrawal of the offer. Berrigan recently Committee for Puerto Rican Decolonization, an organiza out on fight of women criticized Israel's expansionist policies in the Mideast, which tion supporting the independence of Puerto Rico, is spon workers brought slanderous charges from pro-Zionist groups that soring a festival of Puerto Rican poetry. -

Exploring Curriculum Leadership Capacity-Building Through Biographical Narrative: a Currere Case Study

EXPLORING CURRICULUM LEADERSHIP CAPACITY-BUILDING THROUGH BIOGRAPHICAL NARRATIVE: A CURRERE CASE STUDY A dissertation submitted to the Kent State University College of Education, Health and Human Services in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Karl W. Martin August 2018 © Copyright, 2018 by Karl W. Martin All Rights Reserved ii MARTIN, KARL W., Ph.D., August 2018 Education, Health and Human Services EXPLORING CURRICULUM LEADERSHIP CAPACITY-BUILDING THROUGH BIOGRAPHICAL NARRATIVE: A CURRERE CASE STUDY (473 pp.) My dissertation joins a vibrant conversation with James G. Henderson and colleagues, curriculum workers involved with leadership envisioned and embodied in his Collegial Curriculum Leadership Process (CCLP). Their work, “embedded in dynamic, open-ended folding, is a recursive, multiphased process supporting educators with a particular vocational calling” (Henderson, 2017). The four key Deleuzian “folds” of the process explore “awakening” to become lead professionals for democratic ways of living, cultivating repertoires for a diversified, holistic pedagogy, engaging in critical self- examinations and critically appraising their professional artistry. In “reactivating” the lived experiences, scholarship, writing and vocational calling of a brilliant Greek and Latin scholar named Marya Barlowski, meanings will be constructed as engendered through biographical narrative and currere case study. Grounded in the curriculum leadership “map,” she represents an allegorical presence in the narrative. Allegory has always been connected to awakening, and awakening is a precursor for capacity-building. The research design (the precise way in which to study this ‘problem’) will be a combination of historical narrative and currere. This collecting and constructing of Her story speaks to how the vision of leadership isn’t completely new – threads of it are tied to the past. -

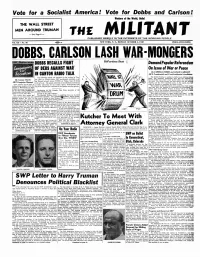

Vote for Dobbs and Carlson! Workers of the World, Unite!

Vote for a Socialist America! Vote for Dobbs and Carlson! Workers of the World, Unite! THE WALL STREET MEN AROUND TRUMAN — See Page 4 — THE MILITANT PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY OCTOBER 4, 1948 Vol. X II -.No. 40 267 PRICE: FIVE CENTS DOBBS, CARLSON LASH WAR <yMONGERS ;$WP flection New* DOBBS RECALLS FI6HT Bp-Partisan Duet flj Demand Popular Referendum OF DEBS AGAINST WAR On Issue o f W ar or Peace By FARRELL DOBBS and GRACE CARLSON IN CANTON RADIO TALK SWP Presidential and Vice-Presidential Candidates The following speech was broadcast to the workers of Can The United Nations is meeting in Paris in an ominous atmos- phere. The American imperialists have had the audacity to ton, Ohio, by Farrell Dobbs, SWP presidential candidate, over By George Clarke launch another war scare a bare month before the voters go to the Mutual network station WHKK on Friday, Sept. 24 from the polls. The Berlin dispute has been thrown into the Security SWP Campaign Manager 4 :45 to 5 p.m. The speech, delivered on the thirtieth anniversary Council; and the entire capitalist press, at this signal, has cast Grace Carlson got the kind of of Debs’ conviction for his Canton speech, demonstrates how aside all restraint in pounding the drums of war. welcome-home reception when she the SWP continues the traditions of the famous socialist agitator. The insolence of the Wan Street rulers stems from their assur arrived in Minneapolis on Sept. ance that they w ill continue to monopolize the government fo r 21 that was proper and deserving another four years whether Truman or Dewey sits in the White fo r the only woman candidate fo r Introduction by Ted Selander, Ohio State Secretary of the House. -

Verizon Strikers Stand up to Attacks on Their Unions

AUSTRALIA $1.50 · CANADA $1.50 · FRANCE 1.00 EURO · NEW ZEALAND $1.50 · UK £.50 · U.S. $1.00 INSIDE Capitalism turns Ecuador quake into a social disaster — PAGE 8 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF WORKING PEOPLE VOL. 80/NO. 18 MAY 9, 2016 Washington, Verizon strikers stand up ‘Workers, Moscow seek to attacks on their unions unions need to impose new Workers rally, answer bosses’ propaganda to control Mideast ‘order’ job safety’ BY MAGGIE TROWE BY JOHN STUDER Washington and Moscow are scram- “My job at Verizon has gotten more bling to hold together an agreement dangerous. I’ve been electrocuted to impose some stability and order in twice on the job, once while they Syria and the broader Mideast region. made me work by myself,” John Hop- But the competing interests of differ- ent ruling classes and factions, includ- Socialist Workers Party ing between the U.S. and Russian gov- ernments themselves, keep getting in candidates speak out the way. Millions of workers and farm- ers in the region pay a terrible price for per, a 25-year outside field technician the ongoing bloodshed. from Rockland County, New York, Talks on ending the five-year war told Socialist Workers Party presi- in Syria hit a stumbling block when dential candidate Alyson Kennedy forces opposing the regime of Presi- and campaign supporter Tony Lane as dent Bashar al-Assad declared a pause they joined a strike rally in Trenton, in their participation April 18. They New Jersey, April 25. “You put your accused the Syrian government of life on the line but the company is un- refusing to end hostilities or to allow CWA District 2-13 grateful.” Strikers and supporters picket Philadelphia Verizon store April 22. -

MPS-0742197.Pdf

MPS-0742197 S.C. No (Plain) POLICE SPECIAL BRANCH Special Report 2nd day of October 1968 . •• t) ‘q • • k• os SUBJECT I Au . On Wednesday, 2nd October, 1968, at 10.30 a.m., Press the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign Autumn Offensive Conference. Ad Hoc Committee held a press conference in a small club room at Conway Mall, Red Lion Square, London, W.C.1, which was attended by some 30 representatives Reference to Papers of national newspapers and the Independent Television Authority. Attached is a printed statement handed to all present. The V.S.C. Ad Hoc Committee was represented by the following persons: Fergus NICHOLSON*/ Communist Party Ernie TTE / V.S.C. National Council William Alan HARRIS/ V.S.C. Ad Hoc Committee Tariq ALI ve V.O.C. National Council. Barney DAVIS I Secretary, Young Communist League Henry WORTI._: Stop It Committee Bill TUT.,:_.:3 Independent Labour Party These persons formed a panel to answer questions put by reporters but skilfully evaded the various issues raised and gave little information other than that contained in the official statement. The main additional points of interest are summarised below. u MPS-0742197 MPS-0742197 NO. 2. TATE said that there were plenty of indications that the number of persons involved on 27th October would be greatly in excess of the previous mass demonstrations of October, 1967, and March, 1968, and he considered that it was possible that 70,000 to 100,000 would tak part in the march. Whereas one bus had brought people from Glasgow in March, 1968 at least four would come this time and about ten other buses would bring people from elsewhere in Scotland. -

I,/I(,I Ulpr Maceo Dixon National of Fice COPY I COPY COPY

I, 14 Charles Lane New York, N.Y. 10014 October 8, 1979 TO ORGANIZERS AND NATIONAL COMMITTEE MEMBERS Dear Comrades, Enclosed are copies of communications between comrades in industry and the National Of fice concern- ing trade-union activity and the role of worker- Bolsheviks. Also included is correspondence between David Herreshoff and Frank Lovell. Herreshoff is a former member of the party. These materials would be usef ul for trade-union fraction heads and coordinators Comradely , I,/i(,i ulpr Maceo Dixon National Of fice COPY I COPY COPY Phoenix, Arizona September 14,1979 Frank Lovell a / o S;i(ITrp 14 Charles Lane New York, N.Y. 10014 Dear comrade Lovell: In this letter I want to ask for your opinion on three questions . The first is what attitude our fractions should, in general, take towards "shop floor" issues in the plants. Before I go further, let me say that I am not of the opinion that our fractions should orient towards these "shop floor" issues and neglect what has been called "broad social questions." I agree generally with the replies to comrade Riehle in the pre-convention discussion by comrades Ryan, Kendrick and Taylor. But none of these articles dealt concretely with what attitude we should take towards "shop floor" questions. We clef initely should talk to as many workers as we can about "broad social issues" and socialism, sell the press, bring contacts to forums, etc. In the process, workers see us as people with intel- ligent ideas and consequently come up to us and ask us what to do about every problem, big and small. -

FEDERAL ELECTIONS 2018: Election Results for the U.S. Senate and The

FEDERAL ELECTIONS 2018 Election Results for the U.S. Senate and the U.S. House of Representatives Federal Election Commission Washington, D.C. October 2019 Commissioners Ellen L. Weintraub, Chair Caroline C. Hunter, Vice Chair Steven T. Walther (Vacant) (Vacant) (Vacant) Statutory Officers Alec Palmer, Staff Director Lisa J. Stevenson, Acting General Counsel Christopher Skinner, Inspector General Compiled by: Federal Election Commission Public Disclosure and Media Relations Division Office of Communications 1050 First Street, N.E. Washington, D.C. 20463 800/424-9530 202/694-1120 Editors: Eileen J. Leamon, Deputy Assistant Staff Director for Disclosure Jason Bucelato, Senior Public Affairs Specialist Map Design: James Landon Jones, Multimedia Specialist TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Preface 1 Explanatory Notes 2 I. 2018 Election Results: Tables and Maps A. Summary Tables Table: 2018 General Election Votes Cast for U.S. Senate and House 5 Table: 2018 General Election Votes Cast by Party 6 Table: 2018 Primary and General Election Votes Cast for U.S. Congress 7 Table: 2018 Votes Cast for the U.S. Senate by Party 8 Table: 2018 Votes Cast for the U.S. House of Representatives by Party 9 B. Maps United States Congress Map: 2018 U.S. Senate Campaigns 11 Map: 2018 U.S. Senate Victors by Party 12 Map: 2018 U.S. Senate Victors by Popular Vote 13 Map: U.S. Senate Breakdown by Party after the 2018 General Election 14 Map: U.S. House Delegations by Party after the 2018 General Election 15 Map: U.S. House Delegations: States in Which All 2018 Incumbents Sought and Won Re-Election 16 II. -

Pew Research Center for the People and the Press

PEW RESEARCH CENTER FOR THE PEOPLE AND THE PRESS NOVEMBER 2004 ELECTION WEEKEND SURVEY FINAL TOPLINE October 27 - 30, 2004 General Public N=2,804 Registered Voters N=2,408 NOTE: ALL NUMBERS IN SURVEY, INCLUDING TREND FIGURES, ARE BASED ON REGISTERED VOTERS EXCEPT WHERE NOTED THOUGHT How much thought have you given to next Tuesday's election, quite a lot, or only a little? Quite (VOL.) Only a (VOL.) DK/ A lot Some Little None Ref. November, 2004 82 3 12 2 1=100 Mid-October, 2004 76 5 15 3 1=100 Early October, 2004 74 4 19 2 1=100 September 22-26, 2004 68 4 23 4 1=100 September 17-21, 2004 66 4 25 4 1=100 Early September, 2004 71 3 22 3 1=100 September 11-14 69 3 23 4 1=100 September 8-10 73 3 21 2 1=100 August, 2004 69 2 26 2 1=100 July, 2004 67 2 28 2 1=100 June, 2004 58 3 36 2 1=100 May, 2004 59 6 30 4 1=100 Late March, 2004 60 4 31 4 1=100 Mid-March, 2004 65 2 31 2 *=100 2000 November, 2000 72 6 19 2 1=100 Late October, 2000 66 6 24 4 *=100 Mid-October, 2000 67 9 19 4 1=100 Early October, 2000 60 8 27 4 1=100 September, 2000 59 8 29 3 1=100 July, 2000 46 6 45 3 *=100 June, 2000 46 6 43 5 *=100 May, 2000 48 4 42 5 1=100 April, 2000 45 7 41 7 *=100 1996 November, 1996 67 8 22 3 *=100 October, 1996 65 7 26 1 1=100 Late September, 1996 61 7 29 2 1=100 Early September, 1996 56 3 36 4 1=100 July, 1996 55 3 41 1 *=100 June, 1996 50 5 41 3 1=100 1992 Early October, 1992 77 5 16 1 1=100 September, 1992 69 3 26 1 1=100 August, 1992 72 4 23 1 *=100 June, 1992 63 6 29 1 1=100 1988 Gallup: November, 1988 73 8 17 2 0=100 Gallup: October, 1988 69 9 20 2 0=100 Gallup: August, 1988 61 10 27 2 0=100 Gallup: September, 1988 57 18 23 2 0=100 1 Q.2 How closely have you been following news about the presidential election.. -

1 Revolutionary Communist Party

·1 REVOLUTIONARY COMMUNIST PARTY (RCP) (RU) 02 STUDENTS FOR A DEMOCRATIC SOCIETY 03 WHITE PANTHER PARTY 04 UNEMPLOYED WORKERS ORGANIZING COMMITTE (UWOC) 05 BORNSON AND DAVIS DEFENSE COMMITTE 06 BLACK PANTHER PARTY 07 SOCIALIST WORKERS PARTY 08 YOUNG SOCIALIST ALLIANCE 09 POSSE COMITATUS 10 AMERICAN INDIAN MOVEMENT 11 FRED HAMPTION FREE CLINIC 12 PORTLAND COMMITTE TO FREE GARY TYLER 13 UNITED MINORITY WORKERS 4 COALITION OF LABOR UNION WOMEN 15 ORGANIZATION OF ARAB STUDENTS 16 UNITED FARM WORKERS (UFW) 17 U.S. LABOR PARTY 18 TRADE UNION ALLIANCE FOR A LABOR PARTY 19 COALITION FOR A FREE CHILE 20 REED PACIFIST ACTION UNION 21 NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR WOMEN (NOW) 22 CITIZENS POSSE COMITATUS 23 PEOPLE'S BICENTENNIAL COMMISSION 24 EUGENE COALITION 25 NEW WORLD LIBERATION FRONT 26 ARMED FORCES OF PUERTO RICAN LIBERATION (FALN) 1 7 WEATHER UNDERGROUND 28 GEORGE JACKSON BRIGADE 29 EMILIANO ZAPATA UNIT 30 RED GUERILLA FAMILY 31 CONTINENTAL REVOLUTIONARY ARMY 32 BLACK LIBERATION ARMY 33 YOUTH INTERNATIONAL PARTY (YIPPY) 34 COMMUNIST PARTY USA 35 AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE 36 COALITION FOR SAFE POWER 37 IRANIAN STUDENTS ASSOCIATION 38 BLACK JUSTICE COMMITTEE 39 PEOPLE'S PARTY 40 THIRD WORLD STUDENT COALITION 41 LIBERATION SUPPORT MOVEMENT 42 PORTLAND DEFENSE COMMITTEE 43 ALPHA CIRCLE 44 US - CHINA PEOPLE'S FRIENDSHIP ASSOCIATION 45 WHITE STUDENT ALLIANCE 46 PACIFIC LIFE COMMUNITY 47 STAND TALL 48 PORTLAND COMMITTEE FOR THE LIBERATION OF SOUTHERN AFRICA 49 SYMBIONESE LIBERATION ARMY 50 SEATTLE WORKERS BRIGADE 51 MANTEL CLUB 52 ......., CLERGY AND LAITY CONCERNED 53 COALITION FOR DEMOCRATIC RADICAL MOVEMENT 54 POOR PEOPLE'S NETWORK 55 VENCEREMOS BRIGADE 56 INTERNATIONAL WORKERS PARTY 57 WAR RESISTERS LEAGUE 58 WOMEN'S INTERNATIONAL LEAGUE FOR PEACE & FREEDOM 59 SERVE THE PEOPLE INC. -

Full Thesis Draft No Pics

A whole new world: Global revolution and Australian social movements in the long Sixties Jon Piccini BA Honours (1st Class) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2013 School of History, Philosophy, Religion & Classics Abstract This thesis explores Australian social movements during the long Sixties through a transnational prism, identifying how the flow of people and ideas across borders was central to the growth and development of diverse campaigns for political change. By making use of a variety of sources—from archives and government reports to newspapers, interviews and memoirs—it identifies a broadening of the radical imagination within movements seeking rights for Indigenous Australians, the lifting of censorship, women’s liberation, the ending of the war in Vietnam and many others. It locates early global influences, such as the Chinese Revolution and increasing consciousness of anti-racist struggles in South Africa and the American South, and the ways in which ideas from these and other overseas sources became central to the practice of Australian social movements. This was a process aided by activists’ travel. Accordingly, this study analyses the diverse motives and experiences of Australian activists who visited revolutionary hotspots from China and Vietnam to Czechoslovakia, Algeria, France and the United States: to protest, to experience or to bring back lessons. While these overseas exploits, breathlessly recounted in articles, interviews and books, were transformative for some, they also exposed the limits of what a transnational politics could achieve in a local setting. Australia also became a destination for the period’s radical activists, provoking equally divisive responses. -

The Role of the Trotskyists in the United Auto Workers, 1939- 1949

The Role of the Trotskyists in the United Auto Workers, 1939- 1949 Victor G. Devinatz Willie Thompson has acknowledged in his survey of the history of the world- wide left, The Left in History: Revolution and Reform in Twentieth-Century Politics, that the Trotskyists "occasionally achieved some marginal industrial influence" in the US trade unions.' However, outside of the Trotskyists' role in the Teamsters Union in Minneapolis and unlike the role of the Communist Party (CP) in the US labor movement that has been well-documented in numerous books and articles, little of a systematic nature has been written about Trotskyist activity in the US trade union movement.' This article's goal is to begin to bridge a gap in the historical record left by other historians of labor and radical movements, by examining the role of the two wings of US Trotskyism, repre- sented by the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) and the Workers Party (WP), in the United Auto Workers (UAW) from 1939 to 1949. In spite of these two groups' relatively small numbers within the auto workers' union and although neither the SWP nor the WP was particularly suc- cessful in recruiting auto workers to their organizations, the Trotskyists played an active role in the UAW as leading individuals and activists, and as an organ- ized left presence in opposition to the larger and more powerful CP. In addi- tion, these Trotskyists were able to exert an influence that was significant at times, beyond their small membership with respect to vital issues confronting the UAW. At various times throughout the 1940s, for example, these trade unionists were skillful in mobilizing auto unionists in opposition to both the no- strike pledge during World War 11, and the Taft-Hartley bill in the postwar peri- od.