Dutch Elm Disease a Non-Native Invasive Wilt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

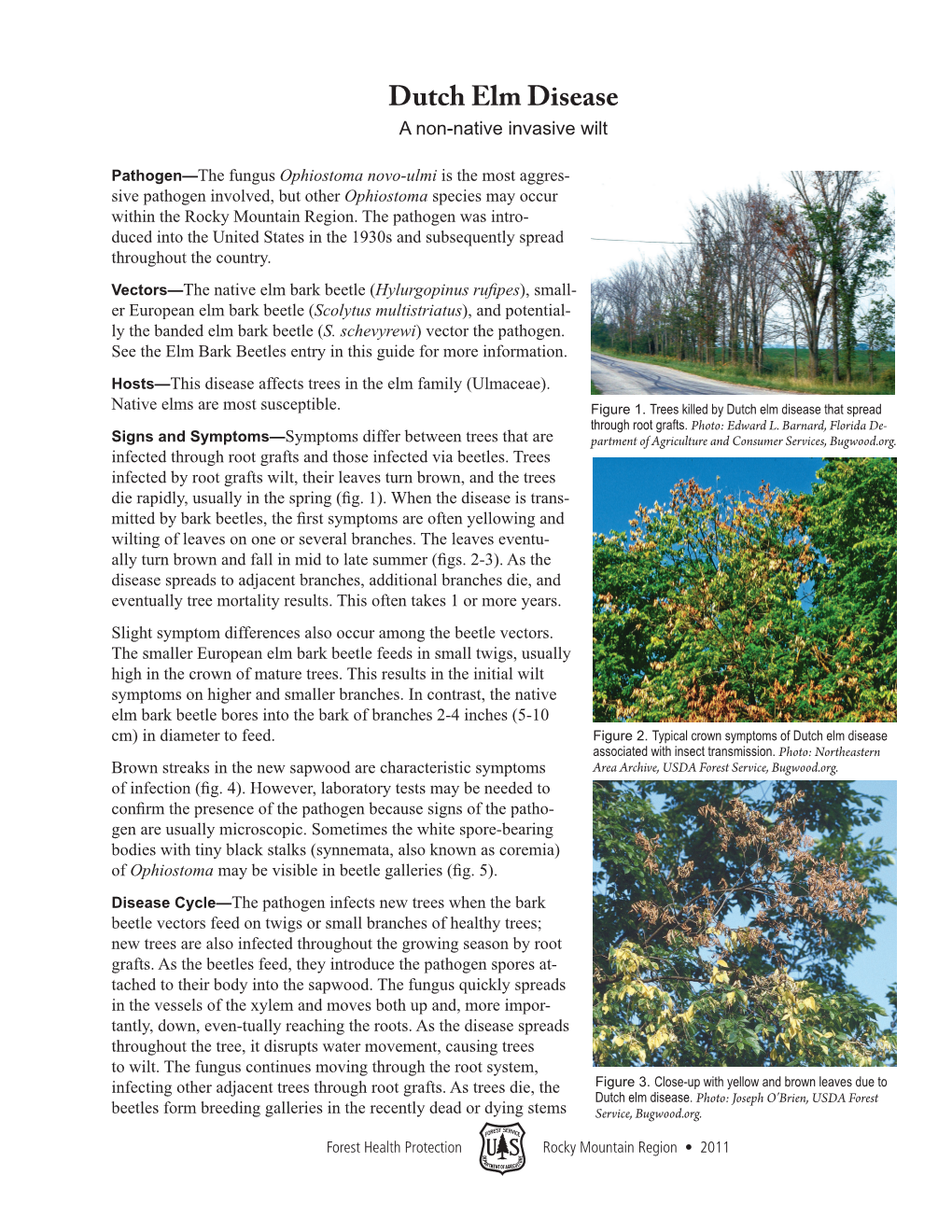

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biology and Management of the Dutch Elm Disease Vector, Hylurgopinus Rufipes Eichhoff (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in Manitoba By

Biology and Management of the Dutch Elm Disease Vector, Hylurgopinus rufipes Eichhoff (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in Manitoba by Sunday Oghiakhe A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Entomology University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2014 Sunday Oghiakhe Abstract Hylurgopinus rufipes, the native elm bark beetle (NEBB), is the major vector of Dutch elm disease (DED) in Manitoba. Dissections of American elms (Ulmus americana), in the same year as DED symptoms appeared in them, showed that NEBB constructed brood galleries in which a generation completed development, and adult NEBB carrying DED spores would probably leave the newly-symptomatic trees. Rapid removal of freshly diseased trees, completed by mid-August, will prevent spore-bearing NEBB emergence, and is recommended. The relationship between presence of NEBB in stained branch sections and the total number of NEEB per tree could be the basis for methods to prioritize trees for rapid removal. Numbers and densities of overwintering NEBB in elm trees decreased with increasing height, with >70% of the population overwintering above ground doing so in the basal 15 cm. Substantial numbers of NEBB overwinter below the soil surface, and could be unaffected by basal spraying. Mark-recapture studies showed that frequency of spore bearing by overwintering beetles averaged 45% for the wild population and 2% for marked NEBB released from disease-free logs. Most NEBB overwintered close to their emergence site, but some traveled ≥4.8 km before wintering. Studies comparing efficacy of insecticides showed that chlorpyrifos gave 100% control of overwintering NEBB for two years as did bifenthrin: however, permethrin and carbaryl provided transient efficacy. -

Bark Beetles

Bark Beetles O & T Guide [O-#03] Carol A. Sutherland Extension and State Entomologist Cooperative Extension Service z College of Agriculture and Home Economics z October 2006 Although New Mexico bark beetle adults are In monogamous species such as the Douglas small, rarely exceeding 1/3 inch in length, they fir beetle, Dendroctonus pseudotsugae, the are very capable of killing even the largest female bores the initial gallery into the host host trees with a mass assault, girdling them or tree, releases pheromones attractive to her inoculating them with certain lethal pathogens. species and accepts one male as her mate. Some species routinely attack the trunks and major limbs of their host trees, other bark beetle species mine the twigs of their hosts, pruning and weakening trees and facilitating the attack of other tree pests. While many devastating species of bark beetles are associated with New Mexico conifers, other species favor broadleaf trees and can be equally damaging. Scientifically: Bark beetles belong to the insect order Coleoptera and the family Scolytidae. Adult “engraver beetle” in the genus Ips. The head is on the left; note the “scooped out” area Metamorphosis: Complete rimmed by short spines on the rear of the Mouth Parts: Chewing (larvae and adults) beetle, a common feature for members of this Pest Stages: Larvae and adults. genus. Photo: USDA Forest Service Archives, USDA Forest Service, www.forestryimages.org Typical Life Cycle: Adult bark beetles are strong fliers and are highly receptive to scents In polygamous species such as the pinyon bark produced by damaged or stressed host trees as beetle, Ips confusus, the male bores a short well as communication pheromones produced nuptial chamber into the host’s bark, releases by other members of their species. -

Dutch Elm Disease Pathogen Transmission by the Banded Elm Bark Beetle Scolytus Schevyrewi

For. Path. 43 (2013) 232–237 doi: 10.1111/efp.12023 © 2013 Blackwell Verlag GmbH Dutch elm disease pathogen transmission by the banded elm bark beetle Scolytus schevyrewi By W. R. Jacobi1,3, R. D. Koski1 and J. F. Negron2 1Department of Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523, USA; 2U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest Research Station, Fort Collins, CO USA; 3E-mail: [email protected] (for correspondence) Summary Dutch Elm Disease (DED) is a vascular wilt disease of Ulmus species (elms) incited in North America primarily by the exotic fungus Ophios- toma novo-ulmi. The pathogen is transmitted via root grafts and elm bark beetle vectors, including the native North American elm bark beetle, Hylurgopinus rufipes and the exotic smaller European elm bark beetle, Scolytus multistriatus. The banded elm bark beetle, Scolytus schevyrewi, is an exotic Asian bark beetle that is now apparently the dominant elm bark beetle in the Rocky Mountain region of the USA. It is not known if S. schevyrewi will have an equivalent vector competence or if management recommendations need to be updated. Thus the study objectives were to: (i) determine the type and size of wounds made by adult S. schevyrewi on branches of Ulmus americana and (ii) determine if adult S. schevyrewi can transfer the pathogen to American elms during maturation feeding. To determine the DED vectoring capability of S. schevyrewi, newly emerged adults were infested with spores of Ophiostoma novo-ulmi and then placed with either in-vivo or in-vitro branches of American elm trees. -

Dutch Elm Disease (DED)

Revival of the American elm tree Ottawa, Ontario (March 29, 2012) – A healthy century old American elm on the campus of the University of Guelph could hold the key to reviving the species that has been decimated by Dutch elm disease (DED). This tree is an example of a small population of mature trees that have resisted the ravages of DED. A study published in the Canadian Journal of Forest Research (CJFR) examines using shoot buds from the tree to develop an in vitro conservation system for American elm trees. “Elm trees naturally live to be several hundred years old. As such, many of the mature elm trees that remain were present prior to the first DED epidemic,” says Praveen Saxena, one of the authors of the study. “The trees that have survived initial and subsequent epidemics potentially represent an invaluable source of disease resistance for future plantings and breeding programs.” Shoot tips and dormant buds were collected from a mature tree that was planted on the University of Guelph campus between 1903 and 1915. These tips and buds were used as the starting material to produce genetic clones of the parent trees. The culture system described in the study has been used successfully to establish a repository representing 17 mature American elms from Ontario. This will facilitate future conservation efforts for the American elm and may provide a framework for conservation of other endangered woody plant species. The American elm was once a mainstay in the urban landscape before DED began to kill the trees. Since its introduction to North America in 1930, Canada in 1945, DED has devastated the American elm population, killing 80%–95% of the trees. -

Elm Bark Beetles Native and Introduced Bark Beetles of Elm

Elm Bark Beetles Native and introduced bark beetles of elm Name and Description—Native elm bark beetle—Hylurgopinus rufipes Eichhoff Smaller European elm bark beetle—Scolytus multistriatus (Marsham) Banded elm bark beetle—S. schevyrewi Semenov [Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae] Three species of bark beetles are associated with elms in the United States: (1) the native elm bark beetle (fig. 1) occurs in Canada and south through the Lake States to Alabama and Mississippi, including Kansas and Nebraska; (2) the introduced smaller European elm bark beetle (fig.2) occurs through- out the United States; and (3) the introduced banded elm bark beetle (fig. 3) is common in western states and is spreading into states east of the Missis- sippi River. Both the smaller European elm bark beetle and the banded elm bark beetle were introduced into the United States from Europe and Asia, respectively. Hylurgopinus rufipes adults are approximately 1/12-1/10 inch (2.2-2.5 mm) long; Scolytus multistriatus adults are approximately 1/13-1/8 inch (1.9-3.1 mm) long; and S. schevyrewi adults are approximately 1/8-1/6 inch (3-4 mm) long. The larvae are white, legless grubs. Hosts—Hosts for the native elm bark beetle include the various native elm Figure 1. Native elm bark beetle. Photo: J.R. species in the United States and Canada, while the introduced elm bark Baker and S.B. Bambara, North Carolina State University, Bugwood.org. beetles also infest introduced species of elms, such as English, Japanese, and Siberian elms. American elm is the primary host tree for the native elm bark beetle. -

2012 Illinois Forest Health Highlights

2012 Illinois Forest Health Highlights Prepared by Fredric Miller, Ph.D. IDNR Forest Health Specialist, The Morton Arboretum, Lisle, Illinois Table of Contents I. Illinois’s Forest Resources 1 II. Forest Health Issues: An Overview 2-6 III. Exotic Pests 7-10 IV. Plant Diseases 11-13 V. Insect Pests 14-16 VI. Weather/Abiotic Related Damage 17 VII. Invasive Plant Species 17 VIII. Workshops and Public Outreach 18 IX. References 18-19 I. Illinois’ Forest Resources Illinois forests have many recreation and wildlife benefits. In addition, over 32,000 people are employed in primary and secondary wood processing and manufacturing. The net volume of growing stock has Figure 1. Illinois Forest Areas increased by 40 percent since 1962, a reversal of the trend from 1948 to 1962. The volume of elms has continued to decrease due to Dutch elm disease, but red and white oaks, along with black walnut, have increased by 38 to 54 percent since 1962. The area of forest land in Illinois is approximately 5.3 million acres and represents 15% of the total land area of the state (Figure 1). Illinois’ forests are predominately hardwoods, with 90% of the total timberland area classified as hardwood forest types (Figure 2). The primary hardwood forest types in the state are oak- hickory, at 65% of all timberland, elm-ash-cottonwood at 23%, and maple-beech which covers 2% of Illinois’ timberland. 1 MERALD ASH BORER (EAB) TRAP TREE MONITORING PROGAM With the recent (2006) find ofMajor emerald ashForest borer (EAB) Types in northeastern Illinois and sub- sequent finds throughout the greater Chicago metropolitan area, and as far south as Bloomington/Chenoa, Illinois area, prudence strongly suggests that EAB monitoring is needed for the extensive ash containing forested areas associated with Illinois state parks, F U.S. -

Entomological Notes: Elm Leaf Beetle

College of Agricultural Sciences Cooperative Extension Entomological Notes Department of Entomology ELM LEAF BEETLE Xanthogaleruca luteola (Muller) The elm leaf beetle is an introduced pest that feeds only on species of elm, Ulmus spp. Although all elm species are subject to attack, this species usually prefers Chinese elm, Ulmus parvifolia. Trees growing in landscapes are more heavily infested than those found in forests. DESCRIPTION Eggs are orange-yellow and spindleshaped. Larvae are small, black, and grublike. At maturity larvae are approximately 13 mm long, dull yellow, and with what appears to be two black stripes down the back. Adults are about 6 mm long, yellowish to olive green with a Figure 1. Life stages of the elm leaf beetle. black stripe along the outer edge of each front wing (Fig. 1). LIFE HISTORY The majority of damage is caused by larvae feeding on This species overwinters as adults in houses, sheds, the lower leaf surface. Trees that lose foliage as a and in protected places outdoors such as under loose result of heavy damage by this pest commonly produce bark of trees or house shingles. In late spring adults a new flush of growth that may be consumed by the leave their overwintering sites, fly to nearby elms, remaining insects found on the host tree. Hibernating mate, and begin laying eggs. Adults eat small, rough adults in homes do not cause structural damage but circular holes into the expanding leaves. may be a nuisance. Eggs are laid on end in groups of 5-25 on the underside Feeding damage by this key pest seldom kills an elm of host plant foliage (Fig. -

Pest Risk Assessment for Dutch Elm Disease

Evira Research Reports 1/2016 Pest Risk Assessment for Dutch elm disease Evira Research Reports 1/2016 Pest Risk Assessment for Dutch elm disease Authors Salla Hannunen, Finnish Food Safety Authority Evira Mariela Marinova-Todorova, Finnish Food Safety Authority Evira Project group Salla Hannunen, Finnish Food Safety Authority Evira Mariela Marinova-Todorova, Finnish Food Safety Authority Evira Minna Terho, City of Helsinki Anne Uimari, Natural Resources Institute Finland Special thanks J.A. (Jelle) Hiemstra, Wageningen UR Tytti Kontula, Finnish Environment Institute Åke Lindelöw, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Michail Yu Mandelshtam, Saint Petersburg State Forest Technical University Alberto Santini, Institute for Sustainable Plant Protection, Italy Juha Siitonen, Natural Resources Institute Finland Halvor Solheim, Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research Joan Webber, Forest Research, UK Cover pictures: Audrius Menkis DESCRIPTION Publisher Finnish Food Safety Authority Evira Title Pest Risk Assessment for Dutch elm disease Authors Salla Hannunen, Mariela Marinova-Todorova Abstract Dutch elm disease (DED) is a fungal disease that causes high mortality of elms. DED and its vector beetles are widely present in most of the countries in the Northern Hemisphere, but they are not known to be present in Finland. DED is a major risk to plant health in Finland. DED and its vectors are moderately likely to enter Finland by natural spread aided by hitchhiking, because they are present in areas close to Finland. Entry via other pathways is much less likely, mainly due to the low volume of trade of untreated wood and plants for planting. DED and its vectors could likely establish in the southern parts of the country, since they currently occur in similar climatic conditions in other countries. -

Infrastructure Update

November | December 2015 Update Infrastructure Rainbow Bridge showing the rocky ramp and inflatable cofferdam Haggart Island Dam Decommissioning Work is now complete on decommissioning the weir under the Rainbow Bridge in Stewart Park (Town of Perth). The old weir has been replaced with a rocky ramp, which is an innovative dam replacement option and river restoration technique. The ramp allows the Tay River to “flow split” into channels which help alleviate flooding in the park. This restoration technique allows for better fish habitat and fish passage as well. The ramp maintains historic upstream water levels that are important to the community while still being aesthetically pleasing. Canoeists and kayakers can now safely navigate downstream. This project is a good balance between community and environmental needs while being a great alternative and innovative method to decommission old and failing dams. One of the construction highlights was the use of an inflatable cofferdam, which enabled work to be completed safety and efficiently with the least impact on the river. MIKE can give you more information at ext. 1176 or michael. yee@ rvca.ca. Motts Mills dam replacement — earthen berm with arched steel pipe culverts and two drop inlet water control structure on the far side Motts Mills Dam Replacement Work to decommission the failing, 63-year-old dam located just off County Road 1 in Elizabethtown- Kitley is now complete. Ducks Unlimited Canada guided construction which saw the installation of an large clay berm across the creek. Within the berm, trenches were dug for two steel and concrete water level control devices (drop inlet structures) and two large arched steel pipe culverts; together these will control water levels in Hutton Marsh. -

Disease Resistant Elm Selections Bruce R

RESEARCH LABORATORY TECHNICAL REPORT Disease Resistant Elm Selections Bruce R. Fraedrich, PhD, Plant Pathology Many hybrids and selections of Asian elm that have reliable resistance to Dutch elm disease (DED) are available for landscape planting. In addition to disease resistance, these elms tolerate urban stress and are adapted to a wide range of soil conditions. These selections are suitable for routine planting in areas where they are adapted to the climate. Descriptions in this report are based primarily on performance of trees growing in the arboretum at the Bartlett Tree Research Laboratories in Charlotte, North Carolina (Zone 8). Accolade Elm in Northern Plains States where low temperatures and low rainfall limit successful use of other cultivars. Ulmus davidiana var. japonica ‘Morton’ A selection of Japanese elm, Accolade elm exhibits Commendation Elm strong resistance to DED and is expected to be resistant to elm yellows. This selection is a favored host Ulmus ‘Morton Stalwart’ of Japanese beetle which can cause defoliation in years A hybrid between U. carpinifolia, U. pumila and U. with heavy outbreaks. Accolade grows rapidly and davidiana var. japonica, Commendation has the has a vase shape with a mature height of 60 feet. It has fastest growth of any of the Morton Arboretum been planted extensively in many Midwestern cities introductions. This cultivar has an upright, vase shape (zone 4). Danada Charm (Ulmus ‘Morton Red Tip’) is but has a distinctively wider crown spread than an open pollinated selection from Accolade and has Accolade or Triumph. The leaves are larger than most similar habit and appearance. Danada Charm does hybrid elms and approach the same size as American not grow as rapidly as Accolade or Triumph in elm. -

Scolytus Koenigi Schevyrew, 1890 (Coleoptera: Curculionidae): New Bark Beetle for the Czech Republic and Notes on Its Biology

JOURNAL OF FOREST SCIENCE, 61, 2015 (9): 377–381 doi: 10.17221/65/2015-JFS Scolytus koenigi Schevyrew, 1890 (Coleoptera: Curculionidae): new bark beetle for the Czech Republic and notes on its biology J. Kašák1, J. Foit1, O. Holuša1, M. Knížek2 1Department of Forest Protection and Wildlife Management, Faculty of Forestry and Wood Technology, Mendel University in Brno, Brno, Czech Republic 2Forestry and Game Management Research Institute, Jíloviště, Czech Republic ABSTRACT: In November 2013, Scolytus koenigi Schevyrew, 1890 was recorded for the first time in the territory of the Czech Republic (Southern Moravia, at two localities near the village of Lednice). This finding represents the northernmost occurrence of this species in Central Europe. Because the knowledge of the S. koenigi bionomy is very limited, the characteristics of 52 galleries on 10 different host tree fragments were studied. The species was found to develop on dead or dying branches and thin trunks of maples Acer campestre L. and Acer platanoides L. with diameters of 3‒12 cm. All of the galleries comprised a 1.6–2.9 mm wide and 8–67 mm long single egg gallery oriented parallelly to the wood grain, with 18‒108 larval galleries emerging almost symmetrically on both sides of the egg gallery. Keywords: Acer, first record, galleries, maple, Scolytinae Scolytus Geoffroy, 1762, a cosmopolitan genus er members of the genus Scolytus that produce an of the subfamily Scolytinae within the family Cur- egg gallery oriented parallelly to the wood grain culionidae (order Coleoptera), includes at least (longitudinal type) (Sarikaya, Knížek 2013). The 61 species from the Palaearctic region (Michalski bionomy of this species is poorly known, and the 1973; Knížek 2011). -

Dutch Elm Disease Had Abundance

A landscape superintendent in ferred to as "the tree towns." ferred to as sanitation by forestry one of the Chicago suburban Elms, oaks and maples are indig- people. Since chemicals haven't towns recently stated that he enous in this sector and grow in yet been compounded that destroy thought Dutch elm disease had abundance. But the elms are either the beetle or its fungus, peaked in 1968 because "we have being cut down. The public works the only holding action possible reached the point where there are department in one of these towns, against the spread of Dutch elm hardly any more elm trees left to Elmhurst, reported that losses in appears to be sanitation. After the die." 1968 ran to 725 trees. That's ap- trees are removed they should be The statement wasn't quite ac- proximately 5 per cent of the elm burned. Otherwise, the beetles curate, but it did emphasize that population, and losses last year aren't going to be destroyed. the disease had taken an alarming were four or five times greater Golf courses that surround Chi- toll in 1968, far higher than in the than five years before. Glen Ellyn, cago are faring somewhat better last six or seven years. The Dutch at the western edge of the tree than municipalities in the battle elm blight was first detected in town sector, reported that nearly against the beetle. Their elm tree the Chicago area in 1955, but not 500 of its 10,000 elms were in- losses in 1968 probably didn't ex- until 1962 did it start making se- fected in 1968, the highest ceed 3 per cent, although a few rious inroads into the elm tree amount on record.