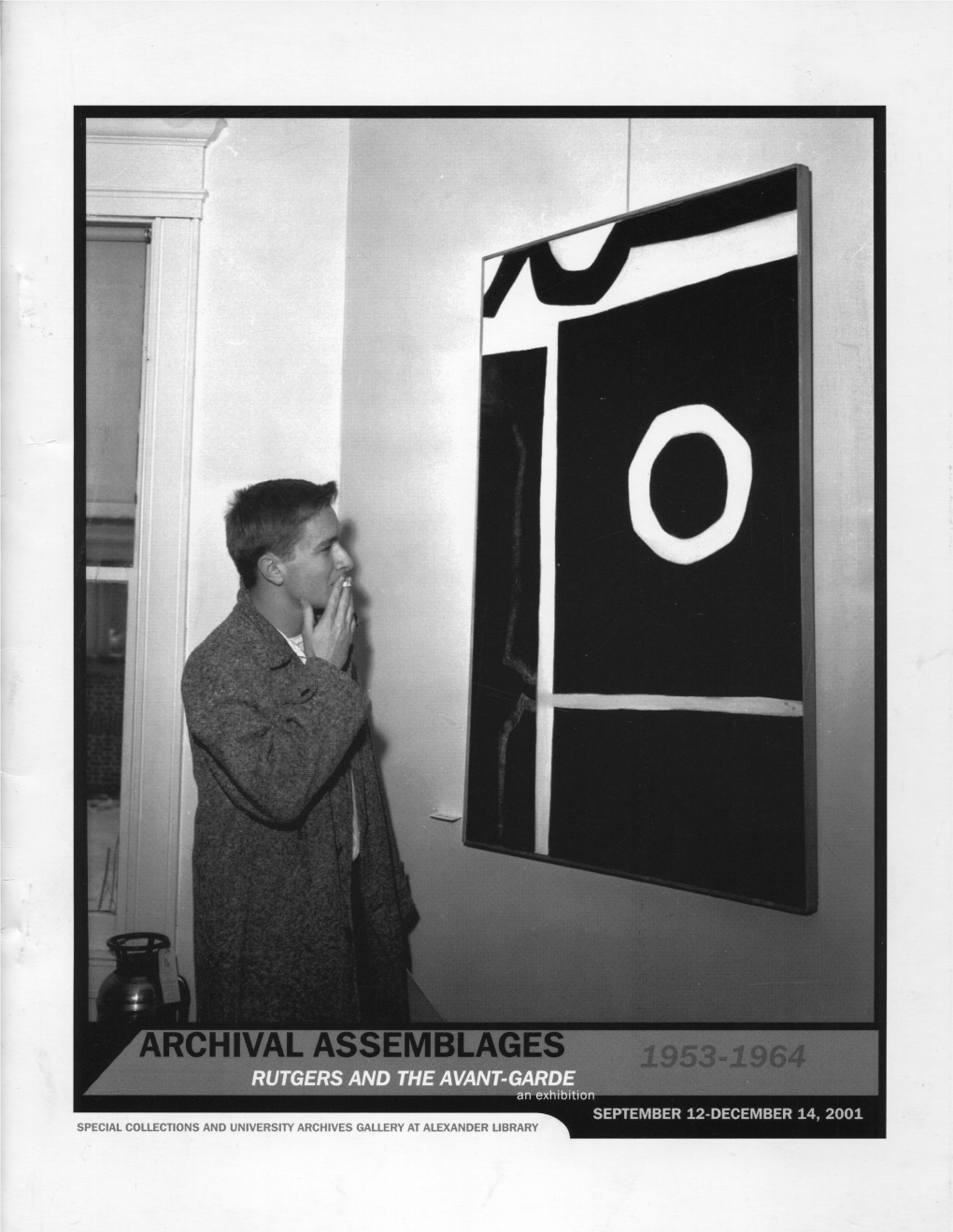

Archival Assemblages: Rutgers and the Avant -Garde, 1953-1964

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Gallery of Art

National Gallery of Art FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Deborah Ziska, Information Officer March 19, 1999 PRESS CONTACT: Patricia O'Connell, Publicist (202) 842-6353 NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART SCULPTURE GARDEN TO OPEN MAY 23 New Acquisitions in Dynamic Space Will Offer Year-Round Enjoyment on the National Mall Washington, D.C. -- On May 23, the National Gallery of Art will open a dynamic outdoor sculpture garden designed to offer year-round enjoyment to the public in one of the preeminent locations on the National Mall. The National Gallery of Art Sculpture Garden is given to the nation by The Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation. The landscaping of the 6.1-acre space provides a distinctive setting for nearly twenty major works, including important new acquisitions of post-World War II sculpture by such internationally renowned artists as Louise Bourgeois, Mark di Suvero, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, and Tony Smith. The Sculpture Garden is located at Seventh Street and Constitution Avenue, N.W., in the block adjacent to the West Building. "We are proud to bring to the nation these significant works of sculpture in one of the few outdoor settings of this magnitude in the country," said Earl A. Powell III, director, National Gallery of Art. "The opening of the Sculpture Garden brings to fruition part of a master plan to revitalize the National Mall that has been in development for more than thirty years. The National Gallery is extremely grateful to the Cafritz Foundation for making this historic event possible." - more - Fourth Street at Constitution Avenue. -

Hans Ulrich Obrist a Brief History of Curating

Hans Ulrich Obrist A Brief History of Curating JRP | RINGIER & LES PRESSES DU REEL 2 To the memory of Anne d’Harnoncourt, Walter Hopps, Pontus Hultén, Jean Leering, Franz Meyer, and Harald Szeemann 3 Christophe Cherix When Hans Ulrich Obrist asked the former director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Anne d’Harnoncourt, what advice she would give to a young curator entering the world of today’s more popular but less experimental museums, in her response she recalled with admiration Gilbert & George’s famous ode to art: “I think my advice would probably not change very much; it is to look and look and look, and then to look again, because nothing replaces looking … I am not being in Duchamp’s words ‘only retinal,’ I don’t mean that. I mean to be with art—I always thought that was a wonderful phrase of Gilbert & George’s, ‘to be with art is all we ask.’” How can one be fully with art? In other words, can art be experienced directly in a society that has produced so much discourse and built so many structures to guide the spectator? Gilbert & George’s answer is to consider art as a deity: “Oh Art where did you come from, who mothered such a strange being. For what kind of people are you: are you for the feeble-of-mind, are you for the poor-at-heart, art for those with no soul. Are you a branch of nature’s fantastic network or are you an invention of some ambitious man? Do you come from a long line of arts? For every artist is born in the usual way and we have never seen a young artist. -

“Print by Print: Series from Dürer to Lichtenstein” Exhibition at the Baltimore Museum of Art

A behind the scenes look: the making of the “Print by Print: Series from Dürer to Lichtenstein” exhibition at The Baltimore Museum of Art One of our recent projects was to make frames for The Baltimore Museum of Art’s “Print by Print: Series from Dürer to Lichtenstein” exhibition. In doing research on the exhibition I noticed the funding came because of the collaboration the museum did with the students from The Johns Hopkins University (JHU) and the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA). Since funding has become much more of an issue in these days of reduced budgets, this caught my attention and I wanted to find out more about the collaboration. I was also interested in sharing with our readers a behind the scenes view of the making of an exhibition. On Friday November 18, 2011 I met with Rena Hoisington, BMA Curator & Department Head of the Department of Prints, Drawings, & Photographs, Alexandra Good, an art history major at JHU, and Micah Cash, BMA Conservation Technician for Paper. Karen Desnick, Metropolitan Picture Framing I was especially intrigued about the funding of this exhibition and the collaborative aspects with the students of The Johns Hopkins University and the Maryland Institute College of Art. Can you elaborate on the funding source and how the collaboration worked? Rena Hoisington, BMA I submitted a proposal for organizing an exhibition of prints in series a couple of years ago. Dr. Elizabeth Rodini, Senior Lecturer in the History of Art Department at The Johns Hopkins University and the Associate Director of the interdisciplinary, undergraduate Program for Museums in Society, then approached the Museum about working on a collaborative project that would result in an exhibition. -

Project Windows 2018 John Singer Sargent and Chicago's Gilded

February 14, 2018 Project Windows 2018 John Singer Sargent and Chicago’s Gilded Age The Art Institute of Chicago “Art is not what you see, but what you make others see.” Edgar Degas Magritte transformed Marc Jacobs ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO AWARD, 2014 Magritte, The Human Condition Lichtenstein reimagined Roy Lichtenstein, Brushstroke with Spatter Macy’s BEST OVER-ALL DESIGN 2015 Vincent brought to life Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait AT&T PEOPLE’S CHOICE AWARDS, 2016 2017 Gauguin: Artist as Alchemist Neiman Marcus Paul Gauguin, Mahana no atua (Day of the God), 1894 ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO AWARD, 2017 Sargent Inspiration - Experiential Sargent Inspiration - Visual Sargent Inspiration - Tactile Benefits Part of a citywide cultural Public Voting Drives traffic and builds celebration awareness Judges Showcase your designers Awards Celebration talent Resources michiganavemag.com/Project-Windows Images + developed merchandise PR + Social Media Advertising Annelise K. Madsen, Ph.D. Gilda and Henry Buchbinder Assistant Curator of American Art John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925) John Singer Sargent and Chicago’s Gilded Age The Fountain, Villa Torlonia, Frascati, Italy (detail), 1907 Oil on canvas 71.4 x 56.5 cm (28 1/8 x 22 1/4 in.) July 1–September 30, 2018 | Regenstein Hall East Friends of American Art Collection, 1914.57 The Art Institute of Chicago Gilded Age Painter of International Renown John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) The Art Institute of Chicago Inspiration Sargent’s art is both old and new, traditional and avant-garde.6 John Singer -

Checklist of the Exhibition

Checklist of the Exhibition Silverman numbers. The numbering system for works in the Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection is explained in Fluxus Codex, edited by Jon Hendricks (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1988), p. 29.ln the present checklist, the Silverman number appears at the end of each item. Dates: Dating of Fluxus works is an inexact science. The system used here employs two, and sometimes three, dates for each work. The first is the probable date the work was initially produced, or when production of the work began. based on information compiled in Fluxus Codex. If it is known that initial production took a specific period, then a second date, following a dash, is MoMAExh_1502_MasterChecklist used. A date following a slash is the known or probable date that a particular object was made. Titles. In this list, the established titles of Fluxus works and the titles of publications, events, and concerts are printed in italics. The titles of scores and texts not issued as independent publications appear in quotation marks. The capitalization of the titles of Fluxus newspapers follows the originals. Brackets indicate editorial additions to the information printed on the original publication or object. Facsimiles. This exhibition presents reprints (Milan: Flash Art/King Kong International, n.d.) of the Fluxus newspapers (CATS.14- 16, 19,21,22,26,28,44) so that the public may handle them. and Marian Zazeela Collection of The preliminary program for the Fluxus Gilbert and lila Silverman Fluxus Collective Works and movement). [Edited by George Maciunas. Wiesbaden, West Germany: Collection Documentation of Events Fluxus, ca. -

Andy Warhol Who Later Became the Most

Jill Crotty FSEM Warhol: The Businessman and the Artist At the start of the 1960s Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg and Robert Rauschenberg were the kings of the emerging Pop Art era. These artists transformed ordinary items of American culture into famous pieces of art. Despite their significant contributions to this time period, it was Andy Warhol who later became the most recognizable icon of the Pop Art Era. By the mid sixties Lichtenstein, Oldenburg and Rauschenberg each had their own niche in the Pop Art market, unlike Warhol who was still struggling to make sales. At one point it was up to Ivan Karp, his dealer, to “keep moving things moving forward until the artist found representation whether with Castelli or another gallery.” 1Meanwhile Lichtenstein became known for his painted comics, Oldenburg made sculptures of mass produced food and Rauschenberg did combines (mixtures of everyday three dimensional objects) and gestural paintings. 2 These pieces were marketable because of consumer desire, public recognition and aesthetic value. In later years Warhol’s most well known works such as Turquoise Marilyn (1964) contained all of these aspects. Some marketable factors were his silk screening technique, his choice of known subjects, his willingness to adapt his work, his self promotion, and his connection to art dealers. However, which factor of Warhol’s was the most marketable is heavily debated. I believe Warhol’s use of silk screening, well known subjects, and self 1 Polsky, R. (2011). The Art Prophets. (p. 15). New York: Other Press New York. 2 Schwendener, Martha. (2012) "Reinventing Venus And a Lying Puppet." New York Times, April 15. -

PRESS RELEASE Art Into Life!

Contact: Anne Niermann / Sonja Hempel Press and Public Relations Heinrich-Böll-Platz 50667 Cologne Tel + 49 221 221 23491 [email protected] [email protected] PRESS RELEASE Art into Life! Collector Wolfgang Hahn and the 60s June 24 – September 24, 2017 Press conference: Thursday, June 22, 11 a.m., preview starts at 10 a.m. Opening: Friday, June 23, 7 p.m. In the 1960s, the Rhineland was already an important center for a revolutionary occurrence in art: a new generation of artists with international networks rebelled against traditional art. They used everyday life as their source of inspiration and everyday objects as their material. They went out into their urban surroundings, challenging the limits of the art disciplines and collaborating with musicians, writers, filmmakers, and dancers. In touch with the latest trends of this exciting period, the Cologne painting restorer Wolfgang Hahn (1924–1987) began acquiring this new art and created a multifaceted collection of works of Nouveau Réalisme, Fluxus, Happening, Pop Art, and Conceptual Art. Wolfgang Hahn was head of the conservation department at the Wallraf Richartz Museum and the Museum Ludwig. This perspective influenced his view of contemporary art. He realized that the new art from around 1960 was quintessentially processual and performative, and from the very beginning he visited the events of new music, Fluxus events, and Happenings. He initiated works such as Daniel Spoerri’s Hahns Abendmahl (Hahn’s Supper) of 1964, implemented Lawrence Weiner’s concept A SQUARE REMOVAL FROM A RUG IN USE of 1969 in his living room, and not only purchased concepts and scores from artists, but also video works and 16mm films. -

Tate Papers Issue 12 2009: Lucy R. Lippard

Tate Papers Issue 12 2009: Lucy R. Lippard http://www.tate.org.uk/research/tateresearch/tatepapers/09autumn/lippa... ISSN 1753-9854 TATE’S ONLINE RESEARCH JOURNAL Landmark Exhibitions Issue Curating by Numbers Lucy R. Lippard Cultural amnesia – imposed less by memory loss than by deliberate political strategy – has drawn a curtain over much important curatorial work done in the past four decades. As this amnesia has been particularly prevalent in the fields of feminism and oppositional art, it is heartening to see young scholars addressing the history of exhibitions and hopefully resurrecting some of its more marginalised events. I have never become a proper curator. Most of the fifty or so shows I have curated since 1966 have been small, not terribly ‘professional’, and often held in unconventional venues, ranging from store windows, the streets, union halls, demonstrations, an old jail, libraries, community centres, and schools … plus a few in museums. I have no curating methodology nor any training in museology, except for working at the Library of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, for a couple of years when I was just out of college. But that experience – the only real job I have ever had – probably prepared me well for the archival, informational aspect of conceptual art. I shall concentrate here on the first few exhibitions I organised in the 1960s and early 1970s, especially those with numbers as their titles. To begin with, my modus operandi contradicted, or simply ignored, the connoisseurship that is conventionally understood to be at the heart of curating. I have always preferred the inclusive to the exclusive, and both conceptual art and feminism satisfied an ongoing desire for the open-ended. -

Geoffrey Hendricks

Geoffrey Hendricks Geoffrey Hendricks was involved in the Judson Gallery in 1967 and 1968. _ n the 1960s, Judson Memorial Church, and especially the Jud- son Gallery in the basement of Judson House, became an impor- tant part of my life. That space at 239 Thompson Street was modest but versatile. Throughout the decade I witnessed many transformations of it as friends and artists, including myself, created work there. The gallery's small size and roughness were perhaps assets. One could work freely and make it into what it had to be. It was a con- tainer for each person's ideas, dreams, images, actions. Three people in particular formed links for me to the space: Allan Kaprow, Al Carmines, and my brother, Jon Hendricks. It must have been through Allan Kaprow that I first got to know about the Judson Gallery. When I began teaching at Rutgers Univer- sity (called Douglass College at the time) in 1956, Allan and I be- came colleagues, and I went to the Judson Gallery to view his Apple Shrine (November 3D-December24, 1960). In that environment one moved through a maze of walls of crumpled newspaper supported on chicken wire and arrived at a square, flat tray that was suspended in the middle and had apples on it. With counterpoints of city and country, it was dense and messy but had an underlying formal struc- ture. His work of the previous few years had had a tremendous im- pact on me: his 18 Happenings in 6 Parts, at the Reuben Gallery (October 1959), his earlier installation accompanied with a text en- titled Notes on the Creation of a Total Art at the Hansa Gallery (February 1958), and his first happening in Voorhees Chapel at Douglass College (April 1958). -

FRED SANDBACK Born 1943 in Bronxville, New York

This document was updated on November 14, 2018. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. FRED SANDBACK Born 1943 in Bronxville, New York. Died 2003 in New York, New York. EDUCATION 1957–61 Williston Academy, Easthampton, Massachusetts 1961–62 Theodor-Heuss-Gymnasium, Heilbronn 1962–66 Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, BA 1966–69 Yale School of Art and Architecture, New Haven, Connecticut, MFA SOLO EXHIBITIONS 1968 Fred Sandback: Plastische Konstruktionen. Konrad Fischer Galerie, Düsseldorf. May 18–June 11, 1968 Fred Sandback. Galerie Heiner Friedrich, Munich. October 24–November 17, 1968 1969 Fred Sandback: Five Situations; Eight Separate Pieces. Dwan Gallery, New York. January 4–January 29, 1969 Fred Sandback. Ace Gallery, Los Angeles. February 13–28, 1969 Fred Sandback: Installations. Museum Haus Lange, Krefeld. July 5–August 24, 1969 [catalogue] 1970 Fred Sandback. Dwan Gallery, New York. April 4–30, 1970 Fred Sandback. Galleria Françoise Lambert, Milan. Opened November 5, 1970 Fred Sandback. Galerie Yvon Lambert, Paris. Opened November 13, 1970 Fred Sandback. Galerie Heiner Friedrich, Munich. 1970 1971 Fred Sandback. Galerie Heiner Friedrich, Munich. January 27–February 13, 1971 Fred Sandback. Galerie Reckermann, Cologne. March 12–April 15, 1971 Fred Sandback: Installations; Zeichnungen. Annemarie Verna Galerie, Zurich. November 4–December 8, 1971 1972 Fred Sandback. Galerie Diogenes, Berlin. December 2, 1972–January 27, 1973 Fred Sandback. John Weber Gallery, New York. December 9, 1972–January 3, 1973 Fred Sandback. Annemarie Verna Galerie, Zürich. Opened December 19, 1972 Fred Sandback. Galerie Heiner Friedrich, Munich. 1972 Fred Sandback: Neue Arbeiten. Galerie Reckermann, Cologne. -

Fluxus Family Reunion

FLUXUS FAMILY REUNION - Lying down: Nam June Paik; sitting on the floor: Yasunao Tone, Simone Forti; first row: Yoshi Wada, Sara Seagull, Jackson Mac Low, Anne Tardos, Henry Flynt, Yoko Ono, La Monte Young, Peter Moore; second row: Peter Van Riper, Emily Harvey, Larry Miller, Dick Higgins, Carolee Schneemann, Ben Patterson, Jon Hendricks, Francesco Conz. (Behind Peter Moore: Marian Zazeela.) Photo by Josef Astor taken at the Emily Harvey Gallery published in Vanity Fair, July 1993. EHF Collection Fluxus, Concept Art, Mail Art Emily Harvey Foundation 537 Broadway New York, NY 10012 March 7 - March 18, 2017 1PM - 6:30PM or by appointment Opening March 7 - 6pm The second-floor loft at 537 Broadway, the charged site of Fluxus founder George Maciunas’s last New York workspace, and the Grommet Studio, where Jean Dupuy launched a pivotal phase of downtown performance art, became the Emily Harvey Gallery in 1984. Keeping the door open, and the stage lit, at the outset of a new and complex decade, Harvey ensured the continuation of these rare—and rarely profitable—activities in the heart of SoHo. At a time when conventional modes of art (such as expressive painting) returned with a vengeance, and radical practices were especially under threat, the Emily Harvey Gallery became a haven for presenting work, sharing dinners, and the occasional wedding. Harvey encouraged experimental initiatives in poetry, music, dance, performance, and the visual arts. In a short time, several artist diasporas made the gallery a new gravitational center. As a record of its founder’s involvements, the Emily Harvey Foundation Collection features key examples of Fluxus, Concept Art, and Mail Art, extending through the 1970s and 80s. -

190 Books People of Color. an Angry Brian Freeman

190 Books people of color. An angry Brian Freeman (“When We Were Warriors”) chal- lenges his black community: “Why do we other each other so in a community of others?” (250). Randy Gener (“The Kids Stay in the Picture, or, Toward a New Queer Theater”) offers hope with School’s OUT, a public program in New YorkCity that brings together queer teenagers of color with theatre pro- fessionals to “explore the thistly themes in their lives—coming out, race, loneliness, sex, dreams and fears of the future, homophobia, racism, and AIDS—through art” (255). Another key tension running through the volume concerns the functions of queer theatre. Whereas coauthors David Roma´n and Tim Miller (“ ‘Preaching to the Converted’ ”) attest to its power to forge community amid political struggle, David Savran (“Queer Theater and the Disarticulation of Identity”) emphasizes its capacity to destabilize and disarticulate identity. Savran claims that “the necessity of multiple identifications and desires that theatre author- izes—across genders, sexualities, races, classes—renders it both the most uto- pian form of cultural production and the queerest” (164). So, Savran asks, why not include John Guare, Mac Wellman, and Suzan Lori-Parks among queer theatre’s luminaries? His query prompts another, one not pursued in the vol- ume’s modern and contemporary coverage: What about the community-building and disarticulating operations of queerness and same-sex desire in ostensibly “straight,” more conventionally canonical theatre? But when it comes to defining the lubricious boundaries of queer theatre, the volume only deserves credit for raising more questions than it answers.