Residential Development Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flooding: What to Do and Who Can Help

Flooding: what to do and who can help This leaflet explains what you can do before, during and after a flood, and what help is available to you from public bodies in Scotland. What you can do You are the first line of defence against floods. It is your responsibility to protect yourself, your family and your property and possessions from flooding. Some actions you can take are listed below. Get prepared • Put the plug in sinks and baths (including overflow) and a sandbag in the toilet bowl to prevent sewage • Make sure you have adequate insurance which covers from flowing back up. flooding. • Turn off gas, electric and water. Unplug electrical items • Know how to turn off your gas, electricity and water and move upstairs if possible. mains supplies. • Avoid contact with flood water as it may be contaminated with sewage. • Prepare a flood kit of essential items such as a torch and first aid kit. • Be aware of hazards below flood water, eg displaced manhole covers. • Consider how to protect your home: buy sandbags or other flood protection products. • Get up-to-date travel information, including closures and disruptions, from Traffic Scotland (0800 028 Check this list of product suppliers: 1414 or online at www.trafficscotland.org ) and www.sepa.org.uk/flooding/being_prepared/protection National Rail Enquiries (08457 48 49 50 or online at _products.aspx www.nationalrail.co.uk ). • Report to your local authority (contact details overleaf) any concerns you have about the condition of a nearby river/stream that may cause flooding. After flood waters have receded Further details at: • Check with Scottish Water before turning water www.sepa.org.uk/flooding/being_prepared.aspx supplies back on: 0845 601 8855 or online at www.scottishwater.co.uk . -

Public West Lothian Council Edinburgh and South East

DATA LABEL: PUBLIC WEST LOTHIAN COUNCIL EDINBURGH AND SOUTH EAST SCOTLAND CITY DEAL JOINT COMMITTEE REPORT BY CHIEF EXECUTIVE A. PURPOSE OF REPORT To agree the proposed governance arrangements for the Edinburgh and South East Scotland City Deal through the establishment of a joint committee. B. RECOMMENDATIONS 1. To agree that the council becomes a member of a joint committee to oversee the governance arrangements for the Edinburgh and South East of Scotland City Region Deal in terms of the appendices to this report 2. To note that the joint committee will have representation from all of the City Region Deal partners (City of Edinburgh, East Lothian, Fife, Midlothian and Scottish Borders Councils, and the higher education, further education and business sectors) 3. To note that Council Executive appointed the Council Leader (or a substitute) to represent the council on the joint committee should the council become a member 4. To agree that the joint committee’s activity be reported regularly to the Development & Transport PDSP, with an annual report to Council Executive and a formal review carried out and reported every two years to ensure the governance arrangements remain fit for purpose C. SUMMARY OF IMPLICATIONS I Council Values Making best use of our resources; working in partnership; being open, honest and accountable II Policy and Legal (including Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973; matters Strategic Environmental relating to strategic environmental assessment, Assessment, Equality equality, health and risk assessments will be -

Aberdeen City Council Aberdeen City IJB Aberdeenshire Council

[email protected] 01786 468784 Aberdeen City Council Aberdeen City IJB Aberdeenshire Council Aberdeenshire IJB Abertay University Accountant in Bankruptcy Angus Council Angus IJB Argyll and Bute Council Argyll and Bute IJB Audit Scotland Ayrshire College Borders College City of Edinburgh Council City of Glasgow College Clackmannanshire and Stirling IJB Clackmannanshire Council Comhairlie nan Eilean Siar Creative Scotland Disclosure Scotland Dumfries and Galloway College Dumfries and Galloway Council Dumfries and Galloway IJB Dundee and Angus College Dundee City Council Dundee City IJB East Ayrshire Council East Ayrshire IJB East Dunbartonshire Council East Dunbartonshire IJB East Lothian Council [email protected] 01786 468784 East Lothian IJB East Renfrewshire Council East Renfrewshire IJB Edinburgh College City of Edinburgh IJB Edinburgh Napier University Education Scotland Falkirk Council Falkirk IJB Fife College Fife Council Fife IJB Food Standards Scotland Forth Valley College Glasgow Caledonian University Glasgow City Council Glasgow City IJB Glasgow Clyde College Glasgow Kelvin College Glasgow School of Art Heriot-Watt University The Highland Council Highlands and Islands Enterprise Highlands and Islands Transport Partnership (HITRANS) Historic Environment Scotland Inverclyde Council Inverclyde IJB Inverness College UHI Lews Castle College UHI Midlothian Council Midlothian IJB [email protected] 01786 468784 Moray College UHI Moray Council Moray IJB New College Lanarkshire Newbattle Abbey College -

West Lothian Council New Local Government Pension Scheme

WEST LOTHIAN COUNCIL NEW LOCAL GOVERNMENT PENSION SCHEME PROCESS FOR DEALING WITH QUERIES /APPEALS ON PENSION SCHEME DECISIONS 1. Employers are required to make certain decisions under the Local Government Pension Scheme rules that could affect an individual’s membership and pension benefits. These include decisions on eligibility to join the new scheme and the rate of member contributions. 2. If you want more information on a decision, it is a good idea to look over information that may have already been sent to you by Lothian Pension Fund or is available on the Council’s Intranet and the Lothian Pension Fund website (www.lpf.org.uk). These sources usually have the answers to the most frequently asked questions. Your Manager may be able to help you access information if you don’t have direct access to a computer. 3. If you have a query about the Council’s decision in your case, it may help to make an informal enquiry first as it may be that the matter can be explained or put right by us. In the first instance you should e-mail [email protected] or alternatively contact 01506 282222. 4. To help us deal with your enquiry as quickly as possible, when you contact us, you should provide the following information: • Full Name • Employee Number • Post Title • Service Area • Details of your query 5. If, following your initial enquiry, you are still dissatisfied with the decision made, you can submit a written appeal on the form attached, setting out why you disagree with the decision and how you wish the matter to be resolved. -

Falkirk Council

DATA LABEL: Public West Lothian Integration Joint Board West Lothian Civic Centre Howden South Road LIVINGSTON EH54 6FF 14 October 2015 A meeting of the West Lothian Integration Joint Board of West Lothian Council will be held within the Strathbrock Partnership Centre, 189 (a) West Main Street, Broxburn EH52 5LH on Tuesday 20 October 2015 at 2:00pm. For Chief Executive BUSINESS Public Session 1. Chair's Remarks 2. Standing Orders - Report by Director (herewith) 3. Order of Business, including notice of urgent business 4. IJB Membership - Report by Director (herewith) 5. Code of Conduct - Report by Director (herewith) 6. Declarations of Interest - Members should declare any financial and non- financial interests they have in the items of business for consideration at the meeting, identifying the relevant agenda item and the nature of their interest. 7. Confirm Draft Minute of Meeting of West Lothian Shadow Integration Joint Board held on Tuesday 25 August 2015. 8. West Lothian Integration Scheme - Report by Director (herewith) 9. First Iteration for SPG Consultation and Comment - Report by Director (herewith) - 1 - DATA LABEL: Public 10. Strategic Planning Group Terms of Reference and Procedures - Report by Director (herewith) 11. Budget and Finance - Report by Director (herewith) 12. Workforce Development / OD Plan - Report by Director (herewith) 13. IJB Member Induction - Report by Director (herewith) 14. Meeting Arrangements and Workplan - Report by Director (herewith) ------------------------------------------------ NOTE For further information contact Anne Higgins, Tel: 01506 281601 or email: [email protected] - 2 - West Lothian Integration Joint Board Date: 20 October 2015 Agenda Item: 2 STANDING ORDERS REPORT BY DIRECTOR A PURPOSE OF REPORT To agree and adopt Standing orders under which the Board’s proceedings shall operate. -

Midlothian Council – Planning Performance Framework Report 2017 - 2018

Midlothian Council – Planning Performance Framework Report 2017 - 2018 Midlothian Council Plann ing Performance Framework 2017 – 2018 Summary Report - Page 1 - Midlothian Council – Planning Performance Framework Report 2017 - 2018 Contents 1 - Introduction ...................................................................................... 3 2 - Development in Midlothian .................................................................... 5 2.1 - Overview ..................................................................................... 5 2.2 - Case Study: Equine Care Unit ............................................................ 5 2.3 - Case Study: 22 Park Road ................................................................. 7 2.4 - Case Study: Social Housing Delivery ..................................................... 9 2.5 - Gorebridge CARS Project ................................................................ 11 2.6 - Craigiebield Hotel ........................................................................ 13 2.7 - Case Study: Out and About Midlothian ................................................ 14 3 - Facilitating Quality Development ........................................................... 17 3.1 - Examples of Planning Team Services .................................................. 17 3.2 - Case Study: New House at Edinburgh & Lasswade Riding Centre ................. 18 3.3 - Case Study: Borthwick Castle Road Housing ......................................... 20 3.4 - Culture of Continuous Improvement ................................................. -

West Lothian Council Committee Information

DATA LABEL: PUBLIC WEST LOTHIAN COUNCIL APPOINTMENTS TO OUTSIDE BODIES REPORT BY THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE A. PURPOSE OF REPORT To make appointments to boards, statutory organisations and other outside bodies. B. RECOMMENDATIONS 1. To appoint members at this meeting to the bodies listed in Appendix 1 to ensure compliance with legal requirements and that the council can do its business effectively 2. To appoint members at this meeting to the bodies listed in Appendix 2, or to agree a process for those appointments to be made later 3. In relation to all outside body appointments, in particular appointments to West Lothian Leisure, to note the summary in paragraph D.3 of the Standards Commission’s Advice for Councillors on Arm's Length External Organisations 4. To appoint the non-councillor members listed in Appendix 3 to the Education Executive and Education (Quality Assurance) Committee, or to any other committees the council may appoint to deal with its education business 5. To appoint the members to the Placing in Schools (Appeals) Committee, as listed in Appendix 4 6. To appoint the members of the West Lothian Local Licensing Forum listed in Appendix 5 7. To note that:- (a) The list in Appendix 6 shows bodies which no longer exist, those which no longer require or desire members to be appointed, and those which have asked for appointments to be deferred (b) Some members are automatically appointed to local trusts and similar bodies, and those are shown in Appendix 7 (c) All members serve ex officio on community councils and community education centre management committees for their ward areas (d) Members are not ex officio members of Parent Councils for schools within their wards, but Parent Councils may choose to co-opt them or invite them to participate in other ways 1 8. -

Integrated Resource Framework Report by Head

West Lothian Community Health and Care Partnership INTEGRATED RESOURCE FRAMEWORK Meeting of 12 January 2010 REPORT BY HEAD OF HEALTH SERVICES AND HEAD OF COUNCIL SERVICES Agenda Item 9 SUMMARY The purpose of this report is to further update the Board on actions taken and progress towards the establishment of a test site across Lothian, for the Scottish Government’s Integrated Resource Framework (IRF). RECOMMENDATION Board is asked to note progress and content of the attached Project Initiation Document (PID) (third draft). BACKGROUND Demographic pressures (particularly the projected rise in the number of older people), workforce issues, the need to continually improve health and social care outcomes; and the increasing cost of institutional care means that current patterns of care delivery are not sustainable. Shifting the balance of care is therefore a strategic objective for the Scottish Government, NHS and Local Authorities. The Better Health, Better Care: Action Plan (December 2007) commits the Scottish Government (SG) to develop a Integrated Resource Framework (IRF) that will… “…support strategic joint commissioning and collaborative contracts to deliver local shifts in the balance of care. The approach may include the development of collaborative contracts, programme budgets and transitional funding as enablers of change”. In essence the IRF is recognised as a way to assist Community Health Partnerships (CHPs) and councils to shift the balance of care (and improve access, manage demand, reduce unnecessary referrals to specialist services and provide better community care services) through having, “a broader range of delegated resources and greater flexibility of decision making.” As outlined in a previous paper to Board (13th October 2009) IRF is being jointly developed by the Scottish Government, NHS Scotland and COSLA, through the National Shifting the Balance of Care Delivery Group. -

Renfrewshire Council West Lothian Council Scottish Borders Council

1192 THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE FRIDAY 25 MAY 2001 Renfrewshire Council West Lothian Council TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING (LISTED BUILDINGS PLANNING APPLICATION AND BUILDINGS IN CONSERVATION AREAS) The Council has received the following application which it is (SCOTLAND) REGULATIONS 1975 required to advertise. Notice to be Published in Accordance with Regulations 5 Applicant Proposal Days for Application for Listed Building Consent, listed below, together Comment with the plans and other documents submitted with them may be 0409/LBC/01 Listed Building Consent for the (S9) examined at the Planning and Transport Department, HQ South construction of 3 liftwells and motor 21 days Building, Cotton Street, Paisley between the hours of 8.45am and room and amendment to flat design 4.45 pm, Monday to Thursday and 8.45am to 3.55 pm, Friday. at St Magdalenes Distillery, Written comments may be made to the Director of Planning and St Magdalenes, Linlithgow Transport at the address below within 21 days from the date of The application may be inspected at the Development & Building publication of this notice. Control Department, County Buildings, High Street, Linlithgow, between 8.30 and 5.00 (4.00 on Friday). Telephone 01506 775222 Address Description of Works for more details. Laigh Park Formation of two house building plots and Observations on the application should be made in writing to the Park Road formation of two new vehicular accesses Development & Building Control Manager, County Buildings, High Johnstone Street, Linlithgow, within the specified period. -

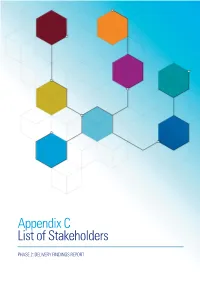

Appendix C List of Stakeholders

Appendix C List of Stakeholders PHASE 2: DELIVERY FINDINGS REPORT 2 / Infrastructure Commission for Scotland / Appendix C Appendix C List of Stakeholders Engagement Initial Call for Organisation Evidence Phase 1 Phase 2 A96 Action n Abellio l Aberdeen City Council n l l Aberdeen City Region Economic Strategy Group n Aberdeenshire Council l l Abundance Investment n ACR Economic Strategy Group l Addleshaw Goddard l Advisian l Amey l Angus Council n l Arancha Arnal n Arcadis n l Architecture and Design Scotland n l l Argyll and Bute Council n Association for Consultancy and Engineering n Association of Town and City Management n Ayrshire and Arran Health Board l Ayrshire Roads Alliance l Balfour Beatty l BT (Scotland) l BT Group Plc n Built Environment Forum Scotland n l Cairngorms l CALA Homes l Caledonian Maritime Assets Limited n Cisco International Limited n Citizen Advice Scotland (CAS) n City Fibre Holdings Ltd n City of Edinburgh Council n l l City of Helsinki l Civil Engineering Contractors Association (CECA) Scotland n l Clackmannanshire Council l Infrastructure Commission for Scotland / Appendix C / 3 Engagement Initial Call for Organisation Evidence Phase 1 Phase 2 CLEAR Buckhaven & Methil n Climate Change and Land Reform Committee l Clyde Gateway n l l Clydeplan l l Colleges Scotland n Comhairle nan Eilean Siar n l l Common Weal n l Confederation of British Industry Scotland (CBI Scotland) n l Confederation of Passenger Transport UK n Construction Industry Training Board – Northern Ireland (CITB NI) l Construction Industry Training -

Members in Scotland

Members in Scotland Page 1 01 June 2021 Mr Kevin Bell BSC MRICS Mr Scott Beveridge MRICS Mr Dougie Bowers MRICS Partner Senior Surveyor Principal Surveyor J+ E Shepherd VOA DVS Valuation Office Agency 22 Miller Road AYR 123 St Vincent Street Elgin House KA7 2AY Glasgow 20 Haymarket Yards G2 5EA Edinburgh 01292 267987 EH12 5WN 03000502779 07917086764 Mrs Merle Boyd Mrs Caroline Campbell MRICS Mr Sydney Davison BSc MRICS Director Associate Director Principal Valuer Savills UK Ltd Savills Valuation Office Agency Earn House Lismore House Portcullis House Broxden Business Park 32 Miller Road 21 India Street Lamberkine Drive Ayr Glasgow Perth KA7 2AY G2 4JJ PH1 1RA 01292838186 01738477535 Mr Chris DeVilliers Mr James Dick BSc (Hons) DIP FBOM Mr Peter Keir Doe Chartered Surveryor & Senior Solicitor (Conveyancing) FAAV ACIARB Cenv REV Chartered Town Planner Aberdeenshire Council Immediate Past President - CAAV Director Legal and Governance James Dick Agriculture - Sole Practitioner Keir + Co Land Compensation Woodhill House 1 Netherby Road Muirhouses Farm Westburn Road Cults Grange Aberdeen Aberdeen Errol AB16 5GB AB15 9HL Perth PH2 7TB 01467 530892 07801953066 07813138642 Mr William Doe HND Assoc RICS Mrs Elaine Farquharson - Black Mr Richard Fox BA (Hons) Keir & Co Partner Commercial Property Surveyor and Land 29 Barossa Place Brodies LLP Agent Perth Brodies House MORRIS PROPERTY MANAGEMENT Ltd PH1 5EP 31-33 Union Grove 29a Victoria Road Aberdeen Gourock 01738 448141 AB10 6SD PA19 1DH 01224392242 01475 650600 Members in Scotland Page 2 01 June -

Possible (Non Exhaustive) List of Hub South East Projects (2021-2025)

Possible (non exhaustive) list of Hub South East projects (2021-2025) Participant Project City of Edinburgh Council Brunstane/Newcraighall PS City of Edinburgh Council Bullyeon Road PS (S. Queensferry) City of Edinburgh Council Craigmount High School extension City of Edinburgh Council Rising Rolls – Sciennes, Castleview, Kirkliston,Ratho,Deanpark and Echline primary schools and Portobello High School City of Edinburgh Council St. Catherine’s PS replacement City of Edinburgh Council Trinity Academy Phase 2 City of Edinburgh Council Wester Hailes Education Centre City of Edinburgh Council Collections hub (archive store) City of Edinburgh Council Care Facility East Lothian Council Wallyford Secondary School East Lothian Council Secondary School(s) extension/refurbishment project East Lothian Council Primary School(s) extension/refurbishment project East Lothian Council Health and Social Care housing provision East Lothian Council Social and Affordable Housing East Lothian Council Care home and community hospital reprovisioning Midlothian Council Beeslack High School Replacement (A701 project) Midlothian Council Mayfield Primary School Campus Midlothian Council Penicuik High School – refurbishment/Extension West Lothian Council Beatlie ASN school West Lothain Council Bangour PS West Lothian Council East Calder PS West Lothian Council Pinewood ASN school West Lothian Council Winchburgh PS West Lothian Council Gavieside PS West Lothian Council Broxburn PS West Lothian Council Replacement Secondary School Scottish Borders Council Earlston Primary