The Val Marie Elevator a Living Heritage Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saskatchewan Birding Trail Experience (Pdf)

askatchewan has a wealth of birdwatching opportunities ranging from the fall migration of waterfowl to the spring rush of songbirds and shorebirds. It is our hope that this Birding Trail Guide will help you find and enjoy the many birding Slocations in our province. Some of our Birding Trail sites offer you a chance to see endangered species such as Piping Plovers, Sage Grouse, Burrowing Owls, and even the Whooping Crane as it stops over in Saskatchewan during its spring and fall migrations. Saskatchewan is comprised of four distinct eco-zones, from rolling prairie to dense forest. Micro-environments are as varied as the bird-life, ranging from active sand dunes and badlands to marshes and swamps. Over 350 bird species can be found in the province. Southwestern Saskatchewan represents the core of the range of grassland birds like Baird's Sparrow and Sprague's Pipit. The mixed wood boreal forest in northern Saskatchewan supports some of the highest bird species diversity in North America, including Connecticut Warbler and Boreal Chickadee. More than 15 species of shorebirds nest in the province while others stop over briefly en-route to their breeding grounds in Arctic Canada. Chaplin Lake and the Quill Lakes are the two anchor bird watching sites in our province. These sites are conveniently located on Saskatchewan's two major highways, the Trans-Canada #1 and Yellowhead #16. Both are excellent birding areas! Oh! ....... don't forget, birdwatching in Saskatchewan is a year round activity. While migration provides a tremendous opportunity to see vast numbers of birds, winter birding offers you an incomparable opportunity to view many species of owls and woodpeckers and other Arctic residents such as Gyrfalcons, Snowy Owls and massive flocks of Snow Buntings. -

An Extra-Limital Population of Black-Tailed Prairie Dogs, Cynomys Ludovicianus, in Central Alberta

46 THE CANADIAN FIELD -N ATURALIST Vol. 126 An Extra-Limital Population of Black-tailed Prairie Dogs, Cynomys ludovicianus, in Central Alberta HELEN E. T REFRY 1 and GEOFFREY L. H OLROYD 2 1Environment Canada, 4999-98 Avenue, Edmonton, Alberta T6B 2X3 Canada; email: [email protected] 2Environment Canada, 4999-98 Avenue, Edmonton, Alberta T6B 2X3 Canada Trefry, Helen E., and Geoffrey L. Holroyd. 2012. An extra-limital population of Black-tailed Prairie Dogs, Cynomys ludovicianus, in central Alberta. Canadian Field-Naturalist 126(1): 4 6–49. An introduced population of Black-tailed Prairie Dogs, Cynomys ludovicianus, has persisted for the past 50 years east of Edmonton, Alberta, over 600 km northwest of the natural prairie range of the species. This colony has slowly expanded at this northern latitude within a transition ecotone between the Boreal Plains ecozone and the Prairies ecozone. Although this colony is derived from escaped animals, it is worth documenting, as it represents a significant disjunct range extension for the species and it is separated from the sylvatic plague ( Yersina pestis ) that threatens southern populations. The unique northern location of these Black-tailed Prairie Dogs makes them valuable for the study of adaptability and geographic variation, with implications for climate change impacts on the species, which is threatened in Canada. Key Words: Black-tailed Prairie Dog, Cynomys ludovicianus, extra-limital occurrence, Alberta. Black-tailed Prairie Dogs ( Cynomys ludovicianus ) Among the animals he displayed were three Black- occur from northern Mexico through the Great Plains tailed Prairie Dogs, a male and two females, originat - of the United States to southern Canada, where they ing from the Dixon ranch colony southeast of Val Marie are found only in Saskatchewan (Banfield 1974). -

Saskatchewan and Described in Attachment “1” to This Notice

TransCanada Keystone Pipeline GP Ltd. Keystone XL Pipeline Notice of Proposed Detailed Route Pursuant to Section 34(1)(b) (“Notice”) of the National Energy Board Act IN THE MATTER OF the National Energy Board Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. N-7 (“NEB Act”) and the regulations made thereunder; IN THE MATTER OF the Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity OC-__ approving the general route of the Keystone XL Pipeline (“Pipeline”); AND IN THE MATTER OF an application by TransCanada Keystone Pipeline GP Ltd. (“Keystone”) respecting the determination and approval of the detailed route for the construction of a crude oil pipeline from Hardisty, Alberta to the international border near Monchy, Saskatchewan and described in Attachment “1” to this Notice.. If you anticipate that your lands may be adversely affected by the proposed detailed route of the Keystone Pipeline, you may oppose the proposed detailed route by filing a written statement of opposition with the National Energy Board (“Board”) within thirty (30) days following the publication of this notice. The written statement of opposition must set out the nature of your interest in those lands and the grounds for your opposition to the proposed detailed route. A copy of any such written statement of opposition must be sent to the following addresses: National Energy Board 444 – 7th Avenue SW Calgary, AB T2P 0X8 Attention: Anne-Marie Erickson, Secretary Toll Free Fax: (877) 288-8803 And to: TransCanada Keystone Pipeline GP Ltd. 101 – 6th Avenue SW Calgary, AB T2P 3P4 Attention: Ron Tourigny, Senior Land Representative – Keystone XL Pipeline Project Phone: (403) 920-7380 Fax: (403) 920-2325 Email: [email protected] Where a written statement is filed with the Board within the thirty (30) days of being served this notice, the Board shall forthwith order, subject to certain exceptions as noted below, that a public hearing be conducted within the area in which the lands to which the statement relates are situated with respect to any grounds of opposition set out in any such statement. -

Grasslands Plan Your Visit National Park

Grasslands Plan Your Visit National Park Let our friendly and knowledgeable staff, at both Visitor Centres, help you plan your Grasslands experience and assist you in having a safe and unforgettable adventure! Visitor Centre Hours of Operation West Block Activities Experience the solitude of May 17 - October 14, Daily 9:00 am - 5:00 pm 2019 the wide-open plain as the East Block prairie wind ripples a sea May 17 - September 2, Daily 9:00 am - 7:00 pm September 3 - October 14, Daily 9:00 am - 5:00 pm of grasses beneath the clear blue sky. Two unique Frenchman Valley Campground Kiosk West Block geographic locations: May 17 - September 2, Daily 3:00 pm - 9:00 pm West Block - Discover Contact Us the varied landscapes of West Block Visitor Centre (in Val Marie) 306-298-2257, Toll Free: 1-877-345-2257 the Frenchman River Valley and observe some of Rock Creek Visitor Centre (in East Block, Rock Creek Campground) 306-476-2018 Canada's rarest wildlife. The park is always open. Fees apply. Please visit the East Block - Explore the website for details. breathtaking badlands and discover astonishing dinosaur fossils exposed in Visit our website: Join us on Facebook the eroding layers of earth. parkscanada.gc.ca/ facebook.com/grasslandsnp grasslands Follow us on Twitter ©parkscanada sk Plan your visit to Grasslands National Park. Other Parks Canada Events in Saskatchewan Every Saturday July & August July 20 Frontier Life Waskesiu Children's Festival Fort Walsh National Historic Site Prince Albert National Park July 6 August 24 Louis Riel Relay & Kidfest Symphony Under the Batoche National Historic Site Sky Festival Motherwell Homestead National Historic Site .. -

Saskatchewan Conference Prayer Cycle

July 2 September 10 Carnduff Alida TV Saskatoon: Grace Westminster RB The Faith Formation Network hopes that Clavet RB Grenfell TV congregations and individuals will use this Coteau Hills (Beechy, Birsay, Gull Lake: Knox CH prayer cycle as a way to connect with other Lucky Lake) PP Regina: Heritage WA pastoral charges and ministries by including July 9 Ituna: Lakeside GS them in our weekly thoughts and prayers. Colleston, Steep Creek TA September 17 Craik (Craik, Holdfast, Penzance) WA Your local care facilities Take note of when your own pastoral July 16 Saskatoon: Grosvenor Park RB charge or ministry is included and remem- Colonsay RB Hudson Bay Larger Parish ber on that day the many others who are Crossroads (Govan, Semans, (Hudson Bay, Prairie River) TA holding you in their prayers. Raymore) GS Indian Head: St. Andrew’s TV Saskatchewan Crystal Springs TA Kamsack: Westminister GS This prayer cycle begins a week after July 23 September 24 Thanksgiving this year and ends the week Conference Spiritual Care Educator, Humboldt (Brithdir, Humboldt) RB of Thanksgiving in 2017. St. Paul’s Hospital RB Kelliher: St. Paul GS Prayer Cycle Crossroads United (Maryfield, Kennedy (Kennedy, Langbank) TV Every Pastoral Charge and Special Ministry Wawota) TV Kerrobert PP in Saskatchewan Conference has been 2016—2017 Cut Knife PP October 1 listed once in this one year prayer cycle. Davidson-Girvin RB Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Sponsored by July 30 Imperial RB The Saskatchewan Conference Delisle—Vanscoy RB KeLRose GS Eatonia-Mantario PP Kindersley: St. Paul’s PP Faith Formation Network Earl Grey WA October 8 Edgeley GS Kinistino TA August 6 Kipling TV Dundurn, Hanley RB Saskatoon: Knox RB Regina: Eastside WA Regina: Knox Metropolitan WA Esterhazy: St. -

Saskatchewan High Schools Athletic Association 1948

SASKATCHEWAN HIGH SCHOOLS ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION 1948 – 2018 70 YEARS OF SCHOOL SPORT “MERIT AWARD” to honour people who have given outstanding leadership and service to the SHSAA and to the promotion of high school athletics in the Province of Saskatchewan. A person who has made outstanding contributions to the TOTAL PROGRAM of the SHSAA over a period of time. THE SIXTIES Stanley Gutheridge (1960) Hub, as he was called, had been recognized over the years by many accolades, the naming of Gutheridge Field on the Riverview Collegiate school grounds, his National Basketball Builder Award, and being in the first group to receive SHSAA’s Merit Award in 1960. Hub died in Moose Jaw in 1990. E.W. (Wally) Stinson (1960) Executive Director of the Association from 1948 to 1959. Credited with designing the original districts, using a Wheat Pool map and a ruler dividing the province into districts with equal numbers of high school students. Joe Griffiths (1960) Joe took a position in 1919 with the University of Saskatchewan as its first Physical Education Director. He remained there until his retirement in 1951. In 1960, he received the SHSAA Merit Award for his influence in high school athletics. The most obvious honour bestowed upon this legendary man was the dedication to him of Griffiths Stadium on the university campus. Clarence Garvie (1960) Garvie filled several roles during the years he was involved with SHSAA. He was its first Secretary, and later was President and editor of the first SHSAA yearbook. A member of both the Saskatchewan and Saskatoon Sports Hall of Fame, Garvie retired in 1972. -

Bylaw No. 3 – 08

BYLAW NO. 3 – 08 A bylaw of The Urban Municipal Administrators’ Association of Saskatchewan to amend Bylaw No. 1-00 which provides authority for the operation of the Association under the authority of The Urban Municipal Administrators Act. The Association in open meeting at its Annual Convention enacts as follows: 1) Article V. Divisions Section 22 is amended to read as follows: Subsection (a) DIVISION ONE(1) Cities: Estevan, Moose Jaw, Regina and Weyburn Towns: Alameda, Arcola, Assiniboia, Balgonie, Bengough, Bienfait, Broadview, Carlyle, Carnduff, Coronach, Fleming, Francis, Grenfell, Indian Head, Kipling, Lampman, Midale, Milestone, Moosomin, Ogema, Oxbow, Pilot Butte, Qu’Appelle, Radville, Redvers, Rocanville, Rockglen, Rouleau, Sintaluta, Stoughton, Wapella, Wawota, White City, Whitewood, Willow Bunch, Wolseley, Yellow Grass. Villages: Alida, Antler, Avonlea, Belle Plaine, Briercrest, Carievale, Ceylon, Creelman, Drinkwater, Fairlight, Fillmore, Forget, Frobisher, Gainsborough, Gladmar, Glenavon, Glen Ewen, Goodwater, Grand Coulee, Halbrite, Heward, Kendal, Kennedy, Kenosee Lake, Kisbey, Lake Alma, Lang, McLean, McTaggart, Macoun, Manor, Maryfield, Minton, Montmarte, North Portal, Odessa, Osage, Pangman, Pense, Roch Percee, Sedley, South Lake, Storthoaks, Sun Valley, Torquay, Tribune, Vibank, Welwyn, Wilcox, Windthorst. DIVISION TWO(2) Cities: Swift Current Towns: Burstall, Cabri, Eastend, Gravelbourg, Gull Lake, Herbert, Kyle, Lafleche, Leader, Maple Creek, Morse, Mossbank, Ponteix, Shaunavon. Villages: Abbey, Aneroid, Bracken, -

Val Marie 1953

65 Across the Street is a campground. 8. United Church Grace United Church began its presence in Val Marie 1953. The old structure still stands on Highway 18. The property was sold to a private owner in 2019. The Village of Val Marie To get back to Prairie Wind & Silver Sage, continue along Hwy 18 and then turn right onto Railway Ave. Follow that along Continue walking along 2nd St. S. Turn left onto and then turn right onto Centre St. Walk 1 st Ave and then turn right onto Hwy 4. The all the way to the end and the little red Catholic Church will be on the left hand side. brick schoolhouse will be on the left hand side. 7. Catholic Church Thank you for taking this walking tour. We hope you enjoyed it and learned a lot about the history and culture of V al Marie! Self-Guided PWSS gratefully acknowledges the contributions Prairie Wind & Silver Sage (PWSS) of these major funders and supporters: is a non-profit organization whose mandate is • Canadian Heritage Heritage Tour to work hand in hand with our community and Turn left as you leave the church and continue • Edmonton Community Association Grasslands National Park promoting the walking along Hwy 4 past Centre St. Turn • Government of Saskatchewan right onto Hwy 18 and follow that down until conservation of the native prairie landscapes while • Grasslands National Park, Parks Canada Agency just before Railway Ave. The United Church inviting the exploration and appreciation of prairie • Sask Culture A walk through time... Sask Lotteries will be on the right hand side. -

RODEO NEWS AUGUST 2017 - PAGE 2 2017 Canadian Cowboys’ Association POWERED by OFFICIAL STANDINGS

AUGUST 2017 Daniel Tober At The Pilot Butte Rodeo PHOTOS COURTESY OF www.canadiancowboys.ca CCA RODEO NEWS AUGUST 2017 - PAGE 2 2017 Canadian Cowboys’ Association POWERED BY OFFICIAL STANDINGS ALL AROUND 12 6071C KELLER SHAY (10) ROCKGLEN, SK 2,077.47 5 7589 YOUNG LOGAN (3) CAROLINE, AB 332.00 1 7408C SWITZER CHANSE HAZENMORE, SK 3,973.28 13 3709C DUNHAM KEVIN (6) SOURIS, MB 1,710.72 6 7643 MILLER LACHLAN (4) NANTON, AB 272.00 2 7542C BOHMER CHANCE HILLCREST, AB 2,507.58 14 5373C RADKE CLINT (17) MARYFIELD, SK 1,393.20 7 N7451C WOLFE CJ (2) WYNYARD, SK 168.00 3 1561C LOEPPKY TJ CENTRAL BUTTE, SK 2,506.23 15 6856C LARSON LOGAN (14) SASKATOON SK 1,318.32 8 7081C DELINTE LOGAN (6) LACADENA, SK 153.00 9 7567 HAY LOGAN (2) WILDWOOD, AB 147.00 CANADIAN HIGH POINT AWARD STEER WRESTLING 1 6857C MCLEOD TYCE WALDECK, SK 12,711.83 1 7611 WESTHAVER RILEY (10) HIGH RIVER, AB 5,266.44 NOVICE BULL RIDING 2 6510C MCLEOD TUFTIN WALDECK, SK 11,838.52 2 6559C HARRIS SCOTT (11) STONEWALL, MB 4,987.62 1 J1668C HARTMAN CHAD (4) L ANCER, SK 740.00 3 5942C SIGFUSSON SCOTT DAVIDSON, SK 9,248.76 3 6645C KLOVANSKY KAL (12) QU’APPELLE, SK 3,667.05 2 6761C THUE TYSON (6) BENGOUGH, SK 555.00 4 5643C SWITZER MATT YORKTON, SK 7,685.72 4 7583C SHUCKBURGH RYAN (11) INNISFAIL, AB 3,214.94 3 J7154C DAVIDSON-NORRISH W (7) STRONGFIELD, SK 494.00 5 7253C MCLEOD TEE WALDECK, SK 7,605.86 5 7253C MCLEOD TEE (16) WALDECK, SK 3,085.38 4 J7119C BARROWS WILLIAM (5) FOREMOST AB 487.00 6 2007C SWITZER BLAINE SWIFT CURRENT SK 6,725.48 6 1705 MARCENKO ZANE (16) ROCKGLEN, SK 2,954.88 -

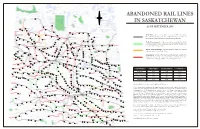

Abandoned Rail Lines in Saskatchewan

N ABANDONED RAIL LINES W E Meadow Lake IN SASKATCHEWAN S Big River Chitek Lake AS OF SEPTEMBER 2008 Frenchman Butte St. Walburg Leoville Paradise Hill Spruce Lake Debden Paddockwood Smeaton Choiceland Turtleford White Fox LLYODMINISTER Mervin Glaslyn Spiritwood Meath Park Canwood Nipawin In-Service: rail line that is still in service with a Class 1 or short- Shell Lake Medstead Marshall PRINCE ALBERT line railroad company, and for which no notice of intent to Edam Carrot River Lashburn discontinue has been entered on the railroad’s 3-year plan. Rabbit Lake Shellbrooke Maidstone Vawn Aylsham Lone Rock Parkside Gronlid Arborfield Paynton Ridgedale Meota Leask Zenon Park Macdowell Weldon To Be Discontinued: rail line currently in-service but for which Prince Birch Hills Neilburg Delmas Marcelin Hagen a notice of intent to discontinue has been entered in the railroad’s St. Louis Prairie River Erwood Star City NORTH BATTLEFORD Hoey Crooked River Hudson Bay current published 3-year plan. Krydor Blaine Lake Duck Lake Tisdale Domremy Crystal Springs MELFORT Cutknife Battleford Tway Bjorkdale Rockhaven Hafford Yellow Creek Speers Laird Sylvania Richard Pathlow Clemenceau Denholm Rosthern Recent Discontinuance: rail line which has been discontinued Rudell Wakaw St. Brieux Waldheim Porcupine Plain Maymont Pleasantdale Weekes within the past 3 years (2006 - 2008). Senlac St. Benedict Adanac Hepburn Hague Unity Radisson Cudworth Lac Vert Evesham Wilkie Middle Lake Macklin Neuanlage Archerwill Borden Naicam Cando Pilger Scott Lake Lenore Abandoned: rail line which has been discontinued / abandoned Primate Osler Reward Dalmeny Prud’homme Denzil Langham Spalding longer than 3 years ago. Note that in some cases the lines were Arelee Warman Vonda Bruno Rose Valley Salvador Usherville Landis Humbolt abandoned decades ago; rail beds may no longer be intact. -

Water Quality of Selected Reservoirs in Southwestern Saskatchewan

WATER QUALITY OF SELECTED RESERVOIRS IN SOUTHWESTERN SASKATCHEWAN G.A. Weiterman Irrigation Branch, Saskatchewan Agriculture Outlook, Saskatchewan Water in both surplus and deficiency causes innumerable problems for Saskatchewan. In this paper I wish to discuss the findings of two years of monitoring of a number of surface water bodies used largely for irrigation in southwestern Saskatchewan. Most of us are concerned only with water quantity. Little thought is given to water quality. We simply turn on the tap and take what's there. Having been raised in southern Saskatchewan the purgative effects of local drinking water supplies did not go unnoticed. The same type of digestive upset which occurs to us can occur in our soils if water quality does not meet certain standards (Cameron & Weiterman, 1986). Spring runoff water has always been assumed to be of suitable quality. Due to the Individual Irrigation Assistance program which includes redevelopment of existing irrigation lands, the need for water quality data on a large number of water supplies in southwestern Saskatchewan was identified. Part of the requirement of this program is the issuance of a soil water certificate. Water quality information is required for the completion of this documentation. After realizing the limited amounts of data available through 1984 and the winter of 1985 a scheduled program of collection of 568 RESERVOIRS (CUBIC DECAMETRES) 1 junction Reservoir (10 850) 11 West Val Marie Reservoir (4 190) 17 Cadi I lac Reservoir (2 220) 2 McDougald Reservoir (860) 12 -

Crop Report Published by the Ministry of Agriculture ISSN 0701 7085 for the Period September 27 to October 3, 2016 Report Number 24, October 6, 2016

Crop Report Published by the Ministry of Agriculture ISSN 0701 7085 For the Period September 27 to October 3, 2016 Report number 24, October 6, 2016 Producers were able to get back into the field for a few days One year ago and make some harvest progress in between the weekend Wet and cool weather slowed rains. Eighty per cent of the 2016 crop has been combined harvest progress. Crop yields and 14 per cent is swathed or ready to straight-cut, were average for most crops. Hard red spring wheat grades according to Saskatchewan Agriculture’s weekly Crop were 27 per cent 1CW, 41 Report. The five-year (2011-2015) average for this time of per cent 2CW, 23 per cent year is 86 per cent combined. 3CW and nine per cent CW Regionally, harvest is furthest advanced in the southeast, feed. where producers have 88 per cent of the crop in the bin. Follow the Crop Report on Eighty-one per cent of the crop is combined in the Twitter @SKAgriculture southwest, 77 per cent in the east-central region, 73 per cent in the west-central and 78 per cent is combined in the Saskatchewan Harvest northwestern and northeastern regions. October 3, 2016 % combined Ninety-five per cent of the lentils, 74 per cent of the durum, Winter wheat 100 79 per cent of the spring wheat, 77 per cent of the canola Fall rye* 100 and 43 per cent of the flax have been combined. Spring wheat 79 Durum 74 Rain set in on the weekend and was fairly general Oats* 75 throughout the province, with areas in west-central and Barley** 86 northwestern regions receiving less than other regions.