Download Exhibition Catalogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DISPLACED BOUNDARIES: GEOMETRIC ABSTRACTION from PICTURES to OBJECTS Monica Amor

REVIEW ARTICLE Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/artm/article-pdf/3/2/101/720214/artm_r_00083.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 DISPLACED BOUNDARIES: GEOMETRIC ABSTRACTION FROM PICTURES TO OBJECTS monica amor suárez, osbel. cold america: geometric abstraction in latin america (1934–1973). exhibition presented by the Fundación Juan march, madrid, Feb 11–may 15, 2011. crispiani, alejandro. Objetos para transformar el mundo: Trayectorias del arte concreto-invención, Argentina y Chile, 1940–1970 [Objects to Transform the World: Trajectories of Concrete-Invention Art, Argentina and Chile, 1940–1970]. buenos aires: universidad nacional de Quilmes, 2011. The literature on what is generally called Latin American Geometric Abstraction has grown so rapidly in the past few years, there is no doubt that the moment calls for some refl ection. The fi eld has been enriched by publications devoted to Geometric Abstraction in Uruguay (mainly on Joaquín Torres García and his School of the South), Argentina (Concrete Invention Association of Art and Madí), Brazil (Concretism and Neoconcretism), and Venezuela (Geometric Abstraction and Kinetic Art). The bulk of the writing on these movements, and on a cadre of well-established artists, has been published in exhibition catalogs and not in academic monographs, marking the coincidence of this trend with the consolidation of major private collections and the steady increase in auction house prices. Indeed, exhibitions of what we can broadly term Latin American © 2014 ARTMargins and the Massachusetts Institute -

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art by Adam Mccauley

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art Adam McCauley, Studio Art- Painting Pope Wright, MS, Department of Fine Arts ABSTRACT Through my research I wanted to find out the ideas and meanings that the originators of non- objective art had. In my research I also wanted to find out what were the artists’ meanings be it symbolic or geometric, ideas behind composition, and the reasons for such a dramatic break from the academic tradition in painting and the arts. Throughout the research I also looked into the resulting conflicts that this style of art had with critics, academia, and ultimately governments. Ultimately I wanted to understand if this style of art could be continued in the Post-Modern era and if it could continue its vitality in the arts today as it did in the past. Introduction Modern art has been characterized by upheavals, break-ups, rejection, acceptance, and innovations. During the 20th century the development and innovations of art could be compared to that of science. Science made huge leaps and bounds; so did art. The innovations in travel and flight, the finding of new cures for disease, and splitting the atom all affected the artists and their work. Innovative artists and their ideas spurred revolutionary art and followers. In Paris, Pablo Picasso had fragmented form with the Cubists. In Italy, there was Giacomo Balla and his Futurist movement. In Germany, Wassily Kandinsky was working with the group the Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter), and in Russia Kazimer Malevich was working in a style that he called Suprematism. -

Michael Boyd Offers Stunning Class in Color at Firestone Loft June 2, 2017 by Charles A

Michael Boyd Offers Stunning Class in Color at Firestone Loft June 2, 2017 by Charles A. Riley II A visit to the stunning Michael Boyd show at Eric Firestone Gallery Loft in New York might make visitors wish they had been pupils in the artist’s design class at Cornell. Exploring the studies along with the paintings in the glowing array gives the sense that the viewer might have dipped into any section of the course that dealt with color. The collective impact of these brilliantly hued abstract works, all produced during a marvelous creative jag from 1970 through 1972, is both contemplative and joyful. Michael Boyd (1936-2015) earned his art degree at the University of Northern Iowa and at one point lived in Ajijic, Mexico; the solar power of some of these canvases can be related to that stint. While teaching a popular Cornell course on design “cen- tered on ergonomics and environmental analysis” (according to a release from the gallery) he maintained a studio in a Soho “Michael Boyd: That’s How the Light Gets In: 1970 – 1972” at Eric loft. Firestone Loft. Courtesy of Eric Firestone Gallery. His earliest paintings were in the Abstract Expressionist mode, until just about the moment when he tightened down his composi- tions into the geometry of the work on view. His work is in the Al- bright Knox, Chrysler and Everson museums. The paintings in the Firestone Loft show were first seen in a solo exhibition at the Max Hutchinson Gallery in New York. The year was 1973. One of the most magnetic works in “Michael Boyd, That’s How the Light Gets In: 1970 - 1972” is Azimuth (1972), its glowing golden core retaining an elemental purity while the delicately modulat- ed lunar blue and lilac pulse around the periphery. -

Bright Futures

the exchange , 1942, TRUE COLORS Clockwise from left: c reative brief Anni and Josef Albers TENAYUCA I TENAYUCA at Black Mountain College in 1938; Anni’s first wall hanging, BRIGHT FUTURES from 1924, at the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation in Bethany, How modernist pioneers Anni and Josef Albers Connecticut; Josef’s furniture in the foun- became art stars for the 21st century. dation’s Trunk gallery; one of Anni’s looms. Opposite: A 1964 BY CAROL KINO study for Josef’s Hom- PHOTOGRAPHY BY DANILO SCARPATI age to the Square series (left) and his newly rediscovered 1942 work Tenayuca I. OW DO YOU MAKE an artist into a key fig- Albers shows in Europe and New York, including Anni ranging from $300,000 to over $2 million. (Zwirner is opens next June in Düsseldorf and travels to London suddenly contacted the gallery about the work. “I got prints, as well as her jewelry, inspired by pre-Colum- ure of art history? Take the case of Josef Albers: Touching Vision, opening October 6 at the doing its part too, with a show opening September 20 that October. “Altogether they seem to know every- one look at it and said, ‘We will buy it,’ ” Fox Weber bian adornments but made with dime-store finds like and Anni Albers, today considered lead- Guggenheim Museum Bilbao—the artist’s first ret- called Josef and Anni and Ruth and Ray, pairing the thing about these artists. And Nick Weber, he tells says. “It’s an extraordinary painting, in mint condi- washers, safety pins and ribbon. -

CUBISM and ABSTRACTION Background

015_Cubism_Abstraction.doc READINGS: CUBISM AND ABSTRACTION Background: Apollinaire, On Painting Apollinaire, Various Poems Background: Magdalena Dabrowski, "Kandinsky: Compositions" Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art Background: Serial Music Background: Eugen Weber, CUBISM, Movements, Currents, Trends, p. 254. As part of the great campaign to break through to reality and express essentials, Paul Cezanne had developed a technique of painting in almost geometrical terms and concluded that the painter "must see in nature the cylinder, the sphere, the cone:" At the same time, the influence of African sculpture on a group of young painters and poets living in Montmartre - Picasso, Braque, Max Jacob, Apollinaire, Derain, and Andre Salmon - suggested the possibilities of simplification or schematization as a means of pointing out essential features at the expense of insignificant ones. Both Cezanne and the Africans indicated the possibility of abstracting certain qualities of the subject, using lines and planes for the purpose of emphasis. But if a subject could be analyzed into a series of significant features, it became possible (and this was the great discovery of Cubist painters) to leave the laws of perspective behind and rearrange these features in order to gain a fuller, more thorough, view of the subject. The painter could view the subject from all sides and attempt to present its various aspects all at the same time, just as they existed-simultaneously. We have here an attempt to capture yet another aspect of reality by fusing time and space in their representation as they are fused in life, but since the medium is still flat the Cubists introduced what they called a new dimension-movement. -

Anni and Josef Albers: Mexican Travels

ANNI AND JOSEF ALBERS: MEXICAN TRAVELS, TOURISTIC EXPERIENCES, AND ARTISTIC RESPONSES by Kathryn Fay Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In Art History Chair: Helen Langa, Ph.D. Juliet Bellow, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Date 2014 American University Washington, D.C. 20016 © COPYRIGHT by Kathryn Fay 2014 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED i ANNI AND JOSEF ALBERS: MEXICAN TRAVELS, TOURISTIC EXPERIENCES, AND ARTISTIC RESPONSES BY Kathryn Fay ABSTRACT Anni and Josef Albers made fourteen trips to Mexico between 1935 and 1967. These visits inspired in a prodigious amount of work, including photo collages, published essays, paintings, drawings, prints, and weavings. Investigating these artistic responses to their experiences in Mexico reveals how Josef and Anni negotiated the cross-cultural inspiration they gained from their travels to create work which they felt matched their Bauhaus-influenced ideals. Examining the subjects that captivated the Alberses, and how they incorporated their experiences into their artistic production, also discloses how they wanted to be understood as artists. As husband and wife, and travel companions, their respective works of art show an interplay of shared opinions and experiences, but also demonstrate what resonated with each artist individually and how each one integrated these influences into their own works of modern, abstract art. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would first like to thank my advisor, Dr. Helen Langa for her enthusiasm, patience, and guidance which helped shaped this thesis in countless ways. I am also grateful to Dr. -

Josef Albers: Josef Albers: to Open Eyes Para Abrir Ojos

BRENDA DANILOWITZ BRENDA DANILOWITZ Josef Albers: Josef Albers: To Open Eyes Para abrir ojos To coincide with an exhibition of Josef Albers’s Para corresponder con la apertura de una exhibi- paintings opening at the Chinati Foundation ción de pinturas de Josef Albers en la Fundación in October 2006, the following pages feature Chinati este octubre, incluimos a continuación un an excerpt from Brenda Danilowitz’s essay in extracto del libro Josef Albers: To Open Eyes por Josef Albers: To Open Eyes, a study of Albers Brenda Danilowitz, un estudio de Albers como as teacher, and essays on the artist written by maestro, y ensayos sobre el artista escritos por Donald Judd over a 30-year period. Donald Judd a lo largo de treinta años. At the very moment Josef and Anni En el preciso momento cuando Josef y Albers found themselves unable to Anni Albers ya no podían imaginar su imagine their future in Germany, the futuro en Alemania, llegó la oferta de offer of a teaching position at Black una cátedra en la Universidad Black Mountain College arrived. This sur- Mountain. Esta sorprendente invitación, prising invitation, which came in the en forma de un telegrama mandado form of a telegram from Philip John- por Philip Johnson, director del nuevo son, then head of the fledgling de- Departamento de Arquitectura y Diseño partment of architecture and design del Museo de Arte Moderno de Nueva at New York’s Museum of Modern York, fue una consecuencia fortuita de Art, was an unintended consequence tres acontecimientos: la dimisión de of three events: John Andrew Rice’s John Andrew Rice de Rolins College en resignation from Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida, los concomitantes Winter Park, Florida; the attendant despidos y dimisiones solidarias de un dismissals and sympathetic resigna- grupo de colegas de Rice, y el estable- the curriculum] was natural to me. -

(Pdf) Download

$5.00 US / $8.00 IN CANADA NOVEMBER 2011 • VOLUME 25 • NUMBER 9 www.professionalartistmag.com CONTENTS FEATURES 4 De-Clutter Your Life BY ELENA PARASHKO 5 Get in the Box BY JODI WALSH 6 Design Is Not a Dirty Word BY MATTHEW DAUB 10 Enhancing the Art Buying Experience How to Turn Buyers into Collectors BY ANNIE STRACK 14 Maximize the Value of Your Art BY RENÉE PHILLIPS, THE ARTREPRENEUR COACH 18 Perspective Technique Tutorial: Drawing Houses on a Steep Hill BY ABIGAIL DAKER 24 Understanding the Aesthetic Power of Geometric Abstraction 18 BY STEPHEN KNUDSEN 28 Nature Sublime: The Paintings of Susan Swartz BY LOUISE BUYO 30 Planning Your Art Business Part 2: A Hobby Versus a Business BY ROBERT REED, PH.D., CFP© COLUMNS 13 Coaching the Artist Within: Prove the Exception BY ERIC MAISEL, PH.D. 16 The Photo Guy: Photographing Artists at Work BY STEVE MELTZER 31 Heart to Heart: Happiness is an Inside Job BY JACK WHITE DEPARTMENTS 4 From the Editor BY KIM HALL 33 Calls to Artists Your best source for art opportunities. Find awards, galleries reviewing portfolios, grants, fellowships, juried shows, festivals, residencies, conferences and more. 40 ArtScuttlebutt.com Member Mark Mulholland BY LOUISE BUYO 40 www.professionalartistmag.com 3 Understanding The Aesthetic Power of Geometric Abstraction BY STEPHEN KNUDSEN THE RENOWNED ART CRITIC Henry Geld- Artists succeed in making effective how the work of artist Jason Hoelscher zahler often used aesthetic intuition as a and memorable work, not through a magic embodies these principles through simple, guiding principle when curating exhibitions formula, but by successfully synthesizing elegant design. -

Josef Albers: Process and Printmaking (1916-1976)

Todos nuestros catálogos de arte All our art catalogues desde/since 1973 JOSEF ALBERS PROCESS AND PRINT MAKING 2014 El uso de esta base de datos de catálogos de exposiciones de la Fundación Juan March comporta la aceptación de los derechos de los autores de los textos y de los titulares de copyrights. Los usuarios pueden descargar e imprimir gra- tuitamente los textos de los catálogos incluidos en esta base de datos exclusi- vamente para su uso en la investigación académica y la enseñanza y citando su procedencia y a sus autores. Use of the Fundación Juan March database of digitized exhibition catalogues signifies the user’s recognition of the rights of individual authors and/or other copyright holders. Users may download and/or print a free copy of any essay solely for academic research and teaching purposes, accompanied by the proper citation of sources and authors. www.march.es FUNDACIÓN JUAN MARCH www.march.es 9 11117884111111 70111 11117562071111111111 111 Josef Albers Process and Printmaking (1916 1976) Fundación Juan March Fundación Juan March 6 Fundación Juan March 6 Fundación Juan March 6 Fundación Juan March Josef Albers Process and Printmaking (1916–1976) Fundación Juan March Fundación Juan March This catalogue and its Spanish edition have been published on the occasion of the exhibition Josef Albers Process and Printmaking (1916–1976) Museu Fundación Juan March, Palma April 2–June 28, 2014 Museo de Arte Abstracto Español, Cuenca July 8–October 5, 2014 And it is a companion publication to the exhibition catalogue Josef Albers: -

Conflicting Visions of Modernity and the Post-War Modern

Socialism and Modernity Ljiljana Kolešnik 107 • • LjiLjana KoLešniK Conflicting Visions of Modernity and the Post-war Modern art Socialism and Modernity Ljiljana Kolešnik Conflicting Visions of Modernity and the Post-war Modern art 109 In the political and cultural sense, the period between the end of World War II and the early of the post-war Yugoslav society. In the mid-fifties this heroic role of the collective - seventies was undoubtedly one of the most dynamic and complex episodes in the recent as it was defined in the early post- war period - started to change and at the end of world history. Thanks to the general enthusiasm of the post-war modernisation and the decade it was openly challenged by re-evaluated notion of (creative) individuality. endless faith in science and technology, it generated the modern urban (post)industrial Heroism was now bestowed on the individual artistic gesture and a there emerged a society of the second half of the 20th century. Given the degree and scope of wartime completely different type of abstract art that which proved to be much closer to the destruction, positive impacts of the modernisation process, which truly began only after system of values of the consumer society. Almost mythical projection of individualism as Marshall’s plan was adopted in 1947, were most evident on the European continent. its mainstay and gestural abstraction offered the concept of art as an autonomous field of Due to hard work, creativity and readiness of all classes to contribute to building of reality framing the artist’s everyday 'struggle' to finding means of expression and design a new society in the early post-war period, the strenuous phase of reconstruction in methods that give the possibility of releasing profoundly unconscious, archetypal layers most European countries was over in the mid-fifties. -

Exploring an Art Paradigm and Its Legacy, Luxembourg & Dayan Presents the Shaped Canvas, Revisited with Works from 1959 - 2014

For Immediate Release Media Contact Andrea Schwan, Andrea Schwan Inc. [email protected], +1 917 371.5023 EXPLORING AN ART PARADIGM AND ITS LEGACY, LUXEMBOURG & DAYAN PRESENTS THE SHAPED CANVAS, REVISITED WITH WORKS FROM 1959 - 2014 THE SHAPED CANVAS, REVISITED Luxembourg & Dayan 64 East 77th Street New York City May 11 – July 3, 2014 Opening Reception: Sunday, May 11th, 6-8PM New York, NY…In the early 1960s, the shaped canvas emerged as a new form of abstract painting that reflected the optimistic spirit of a postwar space-race era when such forms as parallelograms, diamonds, rhomboids, trapezoids, and triangles suggested speed and streamlined stylization. The shaped canvas is frequently described as a hybrid of painting and sculpture, and its appearance on the scene was an outgrowth of central issues of abstract painting; it expressed artists’ desire to delve into real space by rejecting behind-the- frame illusionism. The defining moment for the paradigm occurred in 1964 with The Shaped Canvas, an exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, curated by influential critic Lawrence Alloway with works by Paul Feeley, Sven Lukin, Richard Smith, Frank Stella, and Neil Williams. Alloway’s show defined a key feature of abstraction and revealed the participating artists’ desire to overthrow existing aesthetic hierarchies. Half a century later, the shaped canvas remains robust in art, encompassing an array of approaches and provoking questions about the continued relevance of painting. Coinciding with the 50th anniversary of the Guggenheim Museum’s historic show, Luxembourg & Dayan will present The Shaped Canvas, Revisited, a cross-generational exhibition examining the enduring radicality of the painted shaped canvas and introducing such parallel movements as Pop Art and Arte Povera into discussion of the paradigm’s place in the history of modern art. -

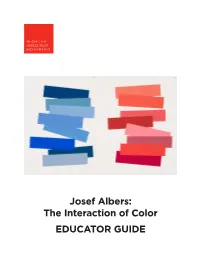

Josef Albers: the Interaction of Color EDUCATOR GUIDE Welcome to the Bechtler

Josef Albers: The Interaction of Color EDUCATOR GUIDE Welcome to the Bechtler Dear Educator, We are thrilled to introduce you to the exhibition Josef Albers: The Interaction of Color. This exhibition features a selection of prints from Josef Albers’ landmark portfolio, The Interaction of Color, originally conceived of as a handbook and teaching aid for artists, educators, and students. This educator guide provides a framework for introducing educators and students to the exhibition and offers suggestions for activities and classroom reflection directly related to the exhibition’s content, key themes, and concepts. We look forward to sharing a world of color with you. Enjoy the experience! Contents 4 Learning Standards 5 About the exhibition Josef Albers: The Interaction of Color 6 Activities 7-11 Select Works from the Exhibition 12 More Activities 13 Links 14-15 About the Bechtler On the cover: Josef Albers (American, born in Germany, 1888-1976), V-3 Lighter and/or Darker- Light Intensity, Lightness from The Interaction of Color portfolio, 1963, printed 1973, silkscreen on paper, 14 7/16 x 10 7/8 x 5 1/2 in. Learning Standards The projects and activities in this educator guide address national and state learning standards for the arts, English language arts, social studies, and technology. National Arts Standards: Visual Arts at a Glance https://www.nationalartsstandards.org/sites/default/files/Visual%20Arts%20at%20a%20 Glance%20-%20new%20copyright%20info.pdf Common Core Standards http://www.corestandards.org/ North Carolina K-12 Standards,