Capital Markets in Eurasia: Two Decades of Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conducting Business in Ukraine Brochure

Conducting Business 2017 in Ukraine All of the information included in this document is for informational purposes only, and may not reflect the most current legal developments, judgments, or settlements. This information is not offered as legal or any other advice on any particular matter. The Firm and the contributing authors expressly disclaim all liability to any person in respect of anything, and in respect of the consequences of anything, done or omitted to be done wholly or partly in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of Baker McKenzie’s Conducting Business in Ukraine brochure. No client or other reader should act or refrain from acting on the basis of any matter contained in this document without first seeking the appropriate legal or other professional advice on the particular facts and circumstances. Conducting Business in Ukraine 2017 Baker McKenzie Renaissance Business Center 24 Bulvarno-Kudriavska St. Kyiv 01601, Ukraine Tel.: +380 44 590 0101 Fax: +380 44 590 0110 [email protected] www.bakermckenzie.com\ukraine Conducting Business in Ukraine Table of Contents Preface ................................................................................................... i 1. Ukraine – An Overview .......................................................... 1 1.1 Geography, Topography and Population .................... 1 1.2 Government, Political and Legal Systems .................. 1 1.3 Regional Structure ...................................................... 6 1.4 Economy .................................................................... -

Evaluation of the Modern Tendencies in the Ukrainian

Baltic Journal of Economic Studies Vol. 1, No. 2, 2015 EVALUATION OF THE MODERN TENDENCIES IN THE UKRAINIAN STOCK MARKET DEVELOPMENT Oleksandr TROFIMCHUK1, Mykhailo TROFIMCHUK2, International Economics and Humanities University named after S. Demyanchuk, Ukraine Abstract. The purpose of the article is to research and critically evaluate the features of functioning and develop- ment the stock market in Ukraine. The main point is to substantiate modern tendencies and to find ways of more efficient development of the Ukrainian stock market. Methodology. The research is based on the analysis of the important aspects which characterize stock market development. They are the volume of trading activity that was done on stock exchanges, level of market capitalization, economic concentration, price policy on market services, and control over the insider information use and manipulation identification. Results. On the basis of volume of trading activity that was done on stock exchanges, features of stock market structure are determined. Comparative analysis between the stock market capitalization level of Ukraine and average world index of stock market capi- talization is done. The level and dynamic of economic concentration is defined. Features of competition between Ukrainian stock exchanges are analyzed. Great attention in research is paid to problems of control over the insider information use and principles of manipulation identification by stock exchanges. Value/originality. The research showed that main amount of trading operations was done in “shadow” stock market, capitalization level decreased and stock market in Ukraine does not meet international standards of transparency. Further research should be focused on problems of ensuring the effective implementation of the basic principles of competition between market participants. -

Markit Index Standard Treatment Index Manual / 7 May 2021

Markit Index Standard Treatment Index Manual / 7 May 2021 Copyright © 2021 IHS Markit Ltd T180614 Markit Index Standard Treatment | CA003 1 Introduction..................................................................................................4 2 Terminology and Notation........................................................................... 5 3 Divisor Methodology....................................................................................8 4 Dividend Points Calculation........................................................................ 9 5 Indices Conversion to Different Currencies.............................................. 10 6 Corporate Actions Treatment Specifications............................................. 11 6.1 General rules of corporate actions treatment....................................11 6.1.1 Price Return, Net Return and Gross Return index adjustments................................................................................... 11 6.1.2 Corporate actions implementation date.................................... 11 6.2 Cash Dividends ................................................................................ 11 6.2.1 Regular Cash Dividend.............................................................11 6.2.1.1 Definition .......................................................................... 11 6.2.1.2 Treatment ......................................................................... 12 6.2.2 Special Cash Dividend..............................................................13 6.2.2.1 -

International Projects

Monthly Issue 7/2012 July 2012 YOUR GUIDE TO THE RUSSIAN STOCK AND DERIVATIVES MARKET International Projects In this Issue: MICEX–RTS announced the launch of trading in futures Valuable information for your business including: on BRICS Indices • The latest news from the With the launch of futures on (Johannesburg Stock Exchange) Russian market BRICS benchmark equity indices from South Africa. on June 6, 2012, all Russian The first stage of the BRICS • Market data for June 2012 investors, for the first time, got exchanges’ cooperation is cross- • MICEX–RTS International an opportunity for easy exposure listing of benchmark equity index projects to these fast-growing markets. derivatives on all the participating • Professional opinion of market This became possible thanks trading venues. As a result, all specialists to the joint efforts of the BRICS MICEX–RTS clients have been exchanges alliance that was provided access to the following formed on 12 October 2011. financial instruments: This is a unique project that opens The initiative brings together • futures contract up new opportunities for economic the BM&FBOVESPA from Brazil, on the BOVESPA Index; cooperation in the BRICS region. MICEX–RTS Exchange from • futures contract The initiative provides more investors Russia, the BSE Ltd (formerly on the Sensex Index; with an easy access to the dynamic known as Bombay Stock • futures contract BRICS economies which will facilitate Exchange) from India, Hong Kong on the Hang Seng Index; liquidity growth in these markets Exchanges and Clearing Limited • futures contract on the and considerably strengthen the (HKEx), and the JSE Limited FTSE/JSE Top40 Index international position of the BRICS alliance in the global economy. -

2020 Market Highlights

2020 Market Highlights Summary 2020 was an extraordinary year for everyone, perhaps rather too eventful. The Covid-19 pandemic, the US presidential election, Brexit, the resignation of Japan’s prime minister Shinzo Abe and increased tension between the US and China created vast economic uncertainty and a flood of pessimistic forecasts. In March we saw market volatility levels comparable only to those of the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 and for months on end, normal working, travel, and leisure arrangements were severely disrupted. When we look at the data, the magnitude of the shock is evident, particularly in March. But what is remarkable is that despite the exceptional circumstances and even during the worst days of the crisis, markets remained open and functioning. In addition, after the peak in uncertainty observed in March, markets quickly recovered. By the end of July, most indicators registered a quick reversal to the activity levels seen before the pandemic, reflecting a strong confidence in the markets and in their role in supporting the economy. Towards the end of the year, the news of the development and approval of several Covid-19 vaccines, the final agreement between the UK and the EU, and the outcome of the US elections seemed to have boosted the confidence of investors and issuers, driving markets to end the year on a high note. Key Indicators Equities • After a sharp drop (20.7%) in Q1, domestic market capitalisation quickly recovered, reaching pre-pandemic levels by the end of Q2. • In November 2020, global market capitalisation passed the 100 USD trillion mark for the first time, ending the year at 109.21 USD trillion, up 19.7% when compared with the end of 2019. -

Doing Data Differently

General Company Overview Doing data differently V.14.9. Company Overview Helping the global financial community make informed decisions through the provision of fast, accurate, timely and affordable reference data services With more than 20 years of experience, we offer comprehensive and complete securities reference and pricing data for equities, fixed income and derivative instruments around the globe. Our customers can rely on our successful track record to efficiently deliver high quality data sets including: § Worldwide Corporate Actions § Worldwide Fixed Income § Security Reference File § Worldwide End-of-Day Prices Exchange Data International has recently expanded its data coverage to include economic data. Currently it has three products: § African Economic Data www.africadata.com § Economic Indicator Service (EIS) § Global Economic Data Our professional sales, support and data/research teams deliver the lowest cost of ownership whilst at the same time being the most responsive to client requests. As a result of our on-going commitment to providing cost effective and innovative data solutions, whilst at the same time ensuring the highest standards, we have been awarded the internationally recognized symbol of quality ISO 9001. Headquartered in United Kingdom, we have staff in Canada, India, Morocco, South Africa and United States. www.exchange-data.com 2 Company Overview Contents Reference Data ............................................................................................................................................ -

Company Profile

CSD Company Profile Organization Name: Public Joint-Stock Company “National Depository of Ukraine” (hereinafter – NDU) Country/ Region: Ukraine Name of CEO: Mindaugas Bakas Capital (US$): 4.3 mln. Number of Officers and Employees: 3 officers and 113 employees Ownership and Governance Ownership structure: (Main Shareholders) • National Bank of Ukraine (NBU) — 25 % • State represented by the National Securities and Stock Market Commission (NSSMC) — 25 % • Corporate non-state pension fund of NBU — 10.98 % • PJSC “State Savings Bank of Ukraine” — 24.99 % • Other stock market participants — 14.03 % Brief History 1997: Law of Ukraine “On National Depository System and Peculiarities of Electronic Circulation of Securities in Ukraine” defined a structure of the National Depository System, NDU role and place in the market 1998: December 18, NBU and NSSMC signed an Agreement on NDU establishment 1999: May 17, NDU was registered with the State NDU became a member of the Association of National Numbering Agencies and started to exercise functions of a National Numbering Agency 2004: NDU became a member of the Association of Eurasian Central Securities Depositories February 2017 1/6 CSD 2006: NDU connected to S.W.I.F.T. system 2008: NDU established a link with Oesterreichische Kontrollbank AG (Austrian CSD) 2009: NDU started on-exchange securities transactions settlement 2010: NDU became a member of the European Central Securities Depositories Association NDU established a link with Clearstream Banking Luxembourg (ICSD) 2012: NDU became a member of -

Inside the Market in This Issue

Monthly Issue 8/2012 August 2012 YOUR GUIDE TO THE RUSSIAN STOCK AND DERIVATIVES MARKET Inside the Market In this Issue: Valuable information for Moscow Exchange and RVC established Russian your business including: Innovation IPO Club • The latest news from the On July 04, 2012 the kick-off Club is aimed at promotion of Russian market meeting of Russian Innovation IPO Russian technological companies • Market data for July 2012 Club was held. Russian Innovation conducting IPOs, discussion of IPO Club is being established with common issues and sharing expe- • Moscow Exchange the support of the Moscow Ex- rience in a casual environment. International projects change Innovation and Investment Anatoly Chubais (RUSNANO), • Professional opinion of market Market (the IIM) and OJSC RVC. Alexander Afanasiev (Moscow specialists Ongoing development of the Rus- Exchange), Igor Agamirzian (RVC), sian economy innovation sector Ivan Rodionov (Higher School of experts of investment and innova- entails building the innovation Economics), Alexander Egorov tion community were among the sector of the Russian public stock (Reksoft), Alexey Kalinin (Baring meeting’s participants. market that is being formed also Vostok Capital Partners), and Ser- In his address to the meeting, within the Innovation and Invest- gey Nedoroslev (Kaskol) participat- Alexander Afanasiev, CEO of ment Market of Moscow Ex- ed in the meeting. In addition, top Moscow Exchange, stressed: “The change. However, at the moment managers and owners of innovative Innovation and Investment Market there is no any official or unofficial companies which have already embodies an opportunity to buy public association representing floated to the public market, first of the future. -

LCSH Section U

U-2 (Reconnaissance aircraft) (Not Subd Geog) U.S. 29 U.S. Bank Stadium (Minneapolis, Minn.) [TL686.L (Manufacture)] USE United States Highway 29 BT Stadiums—Minnesota [UG1242.R4 (Military aeronautics)] U.S. 30 U.S. Bicycle Route System (May Subd Geog) UF Lockheed U-2 (Airplane) USE United States Highway 30 UF USBRS (U.S. Bicycle Route System) BT Lockheed aircraft U.S. 31 BT Bicycle trails—United States Reconnaissance aircraft USE United States Highway 31 U.S.-Canada Border Region U-2 (Training plane) U.S. 40 USE Canadian-American Border Region USE Polikarpov U-2 (Training plane) USE United States Highway 40 U.S. Capitol (Washington, D.C.) U-2 Incident, 1960 U.S. 41 USE United States Capitol (Washington, D.C.) BT Military intelligence USE United States Highway 41 U.S. Capitol Complex (Washington, D.C.) Military reconnaissance U.S. 44 USE United States Capitol Complex (Washington, U-Bahn-Station Kröpcke (Hannover, Germany) USE United States Highway 44 D.C.) USE U-Bahnhof Kröpcke (Hannover, Germany) U.S. 50 U.S. Cleveland Post Office Building (Punta Gorda, Fla.) U-Bahnhof Kröpcke (Hannover, Germany) USE United States Highway 50 UF Cleveland Post Office Building (Punta Gorda, UF Kröpcke, U-Bahnhof (Hannover, Germany) U.S. 51 Fla.) Station Kröpcke (Hannover, Germany) USE United States Highway 51 BT Post office buildings—Florida U-Bahn-Station Kröpcke (Hannover, Germany) U.S. 52 U.S. Coast Guard Light Station (Jupiter Inlet, Fla.) BT Subway stations—Germany USE United States Highway 52 USE Jupiter Inlet Light (Fla.) U-Bahnhof Lohring (Bochum, Germany) U.S. -

MSCI Index Calculation Methodology Index Calculation Methodology for the MSCI Equity Indexes

Index Methodology MSCI Index Calculation Methodology Index Calculation Methodology for the MSCI Equity Indexes February 2014 msci.com Index Methodology MSCI Index Calculation Methodology February 2014 Contents Contents ..................................................................................... 2 Introduction ............................................................................... 5 MSCI Equity Indexes .................................................................. 6 Section 1: MSCI Price Index Methodology ................................ 7 1.1. Price Index Level ............................................................................................... 7 1.1.1. Index Market Capitalization ...................................................................... 7 1.1.2. Example of calculation ............................................................................ 10 1.2. Price Index Level (Alternative Calculation Formula – Contribution Method) .................................................................................................................... 11 1.2.1. Security Contribution to the Index ......................................................... 11 1.2.2. Today’s Initial Security Weight ................................................................ 12 1.2.3. Security Daily Price Return ....................................................................... 13 1.2.4. Example of calculation using contribution ............................................ 15 1.3. Next Day Initial Security Weight ............................................................... -

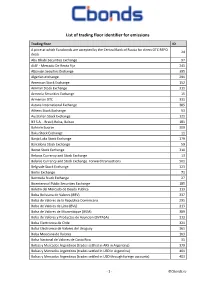

List of Trading Floor Identifier for Emissions

List of trading floor identifier for emissions Trading floor ID A price at which Eurobonds are accepted by the Central Bank of Russia for direct OTC REPO 24 deals Abu Dhabi Securities Exchange 97 AIAF - Mercado De Renta Fija 241 Albanian Secuities Exchange 395 Algerian exchange 291 American Stock Exchange 152 Amman Stock Exchange 311 Armenia Securities Exchange 15 Armenian OTC 331 Astana International Exchange 385 Athens Stock Exchange 53 Australian Stock Exchange 121 B3 S.A. - Brasil, Bolsa, Balcao 181 Bahrain Bourse 309 Baku Stock Exchange 11 Banja Luka Stock Exchange 179 Barcelona Stock Exchange 59 Beirut Stock Exchange 310 Belarus Currency and Stock Exchange 13 Belarus Currency and Stock Exchange. Forward transactions 501 Belgrade Stock Exchange 123 Berlin Exchange 71 Bermuda Stock Exchange 27 Bicentennial Public Securities Exchange 185 Boletin del Mercado de Deuda Publica 113 Bolsa Boliviana de Valores (BBV) 337 Bolsa de Valores de la Republica Dominicana 295 Bolsa de Valores de Lima (BVL) 213 Bolsa de Valores de Mozambique (BVM) 389 Bolsa de Valores y Productos de Asuncion (BVPASA) 313 Bolsa Electronica de Chile 321 Bolsa Electronica de Valores del Uruguay 361 Bolsa Mexicana de Valores 103 Bolsa Nacional de Valores de Costa Rica 31 Bolsas y Mercados Argentinos (trades settled in ARS in Argentina) 379 Bolsas y Mercados Argentinos (trades settled in USD in Argentina) 401 Bolsas y Mercados Argentinos (trades settled in USD through foreign accounts) 403 - 1 - ©Cbonds.ru Trading floor ID BondSpot 69 Borsa Istanbul (International Bonds -

The Reit Statistical and Investment Returns Reporting Manual

Securities Commission Malaysia (SCM) THE REIT STATISTICAL AND INVESTMENT RETURNS REPORTING MANUAL Page 1 Securities Commission Malaysia (SCM) DOCUMENT CONTROL Version Date Author Comments 1.0 31/03/2017 SC Updated as per 3.0.1 28/06/2021 SC tool release v3.0.1 Page 2 Securities Commission Malaysia (SCM) TABLE OF CONTENTS PART A: GENERAL ..................................................................................................................................... 4 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 4 PART B: REPORTING INFORMATION .................................................................................................... 5 2. GENERAL INFORMATION ................................................................................................................. 5 3. REPORTING SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... 6 FM05.M.REIT ............................................................................................................................... 7 FM16.Q.REIT .............................................................................................................................. 19 APPENDIX .................................................................................................................................................... 21 APPENDIX A: ISO CODES .........................................................................................................