Abkhazia Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russian Hybrid Tactics in Georgia

Russian Hybrid Tactics in Georgia Niklas Nilsson SILK ROAD PAPER January 2018 Russian Hybrid Tactics in Georgia Niklas Nilsson © Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program – A Joint Transatlantic Research and Policy Center American Foreign Policy Council, 509 C St NE, Washington D.C. Institute for Security and Development Policy, V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.silkroadstudies.org “Russian Hybrid Tactics in Georgia” is a Silk Road Paper published by the Central Asia- Caucasus Institute and Silk Road Studies Program, Joint Center. The Silk Road Papers Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Joint Center, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Joint Center is a transatlantic independent and non-profit research and policy center. It has offices in Washington and Stockholm and is affiliated with the American Foreign Policy Council and the Institute for Security and Development Policy. It is the first institution of its kind in Europe and North America, and is firmly established as a leading research and policy center, serving a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. The Joint Center is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development in the region. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion regarding the region. The opinions and conclusions expressed in this study are those of -

Foreign Observation of the Illegitimate Elections in South Ossetia and Abkhazia in 2019

FOREIGN OBSERVATION OF THE ILLEGITIMATE ELECTIONS IN SOUTH OSSETIA AND ABKHAZIA IN 2019 Anton Shekhovtsov FOREIGN OBSERVATION OF THE ILLEGITIMATE ELECTIONS IN SOUTH OSSETIA AND ABKHAZIA IN 2019 Anton Shekhovtsov Contents Executive summary _____________________________________ 4 Introduction: Illegitimacy of the South Ossetian “parliamentary” and Abkhaz “presidential elections” ___________ 6 “Foreign observers” of the 2019 “elections” in South Ossetia and Abkhazia ____________________________ 9 Established involvement of “foreign observers” in pro-Kremlin efforts __________________________________ 16 Assessments of the South Ossetian and Abkhaz 2019 “elections” by “foreign observers” _____________________ 21 Conclusion ___________________________________________ 27 Edition: European Platform for Democratic Elections www.epde.org Responsible for the content: Europäischer Austausch gGmbH Erkelenzdamm 59 10999 Berlin, Germany Represented through: Stefanie Schiffer EPDE is financially supported by the European Union and the Federal Foreign Office of Germany. The here expressed opinion does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the donors. Executive summary The so-called “Republic of South Ossetia” and “Republic of Abkhazia” are breakaway regions of Georgia that are recognised as independent sovereign states only by five UN Member States: Russia (which supports their de facto independence by military, economic and political means), Nauru, Nicaragua, Syria and Venezuela. Other entities that recognise South Ossetia and Abkhaz- ia as independent -

Georgia Case Study Part II: Internally Displaced Persons Viewed Externally

Georgia Case Study Part II: Internally Displaced Persons Viewed Externally Brian Frydenborg Experiential Applications – MNPS 703 Allison Frendak-Blume, Ph.D. The problem of internally displaced persons (referred to commonly as IDPs) and international refugees is as old as the problem of war itself. As a special report of The Jerusalem Post notes, “Wars produce refugees” (Radler n.d., par. 1). The post-Cold-War conflicts in Georgia between Georgia, Russian, and Georgia‟s South Ossetia and Abkhazia regions displaced roughly 223,000 people, mostly from the Abkhazia part of the conflict, and the recent fighting between Georgia and Russia/South Ossetia/Abkhazia of August 2008 created 127,000 such IDPs and refugees (UNHCR 2009a, par. 1). A United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) mission even before the 2008 fighting “described the needs of Georgia's displaced as „overwhelming‟” (Ibid., par. 2). This paper will discuss the problem of IDPs in Georgia, particularly as related to the Abkhazian part of the conflicts of the last few decades. It will highlight the efforts of one international organization (IO), the UNHCR, and one non-governmental organization (NGO), the Danish Refugee Council. i. Focus of Paper and Definitions The UN divides people as uprooted by conflict into two categories: refugees and internally displaced persons; the first group refers to people who are “forcibly uprooted” and flee from their nation to another, the second to people who are “forcibly uprooted” and flee to another location within their nation (UNHCR 2009b, par 1). Although there are also IDPs and refugees resulting from the fighting in South Ossetia, this paper will focus on the IDPs from the fighting in and around Abkhazia; refugees from or in Georgia will not be dealt with specifically because the overwhelming majority of people uprooted from their homes in relation to Georgia‟s ethnic conflicts ended up being IDPs (close to 400,000 total current and returned) and less than 13,000 people were classified as refugees from these conflicts (UNHCR 2009a, par. -

Freedom of Religion in Abkhazia and South Ossetia/Tskhinvali Region

Freedom of Religion in Abkhazia and South Ossetia/Tskhinvali Region Brief prehistory Orthodox Christians living in Abkhazia and South Ossetia are considered by the Patriarchate of the Georgian Orthodox Church to be subject to its canonical jurisdiction. The above is not formally denied by any Orthodox Churches. Abkhazians demand full independence and imagine their Church also to be independent. As for South Ossetia, the probable stance of "official" Ossetia is to unite with Alanya together with North Ossetia and integrate into the Russian Federation, therefore, they do not want to establish or "restore" the Autocephalous Orthodox Church. In both the political and ecclesiastical circles, the ruling elites of the occupied territories do not imagine their future together with either the Georgian State or the associated Orthodox Church. As a result of such attitudes and Russian influence, the Georgian Orthodox Church has no its clergymen in Tskhinvali or Abkhazia, cannot manage the property or relics owned by it before the conflict, and cannot provide adequate support to the parishioners that identify themselves with the Georgian Orthodox Church. Although both Abkhazia and South Ossetia have state sovereignty unilaterally recognized by the Russian Federation, ecclesiastical issues have not been resolved in a similar way. The Russian Orthodox Church does not formally or officially recognize the separate dioceses in these territories, which exist independently from the Georgian Orthodox Church, nor does it demand their integration into its own space. Clearly, this does not necessarily mean that the Russian Orthodox Church is guided by the "historical truth" and has great respect for the jurisdiction of the Georgian Orthodox Church in these territories. -

Georgia/Abkhazia

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH ARMS PROJECT HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH/HELSINKI March 1995 Vol. 7, No. 7 GEORGIA/ABKHAZIA: VIOLATIONS OF THE LAWS OF WAR AND RUSSIA'S ROLE IN THE CONFLICT CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY, RECOMMENDATIONS............................................................................................................5 EVOLUTION OF THE WAR.......................................................................................................................................6 The Role of the Russian Federation in the Conflict.........................................................................................7 RECOMMENDATIONS...............................................................................................................................................8 To the Government of the Republic of Georgia ..............................................................................................8 To the Commanders of the Abkhaz Forces .....................................................................................................8 To the Government of the Russian Federation................................................................................................8 To the Confederation of Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus...........................................................................9 To the United Nations .....................................................................................................................................9 To the Organization on Security and Cooperation in Europe..........................................................................9 -

Analyzing the Russian Way of War Evidence from the 2008 Conflict with Georgia

Analyzing the Russian Way of War Evidence from the 2008 Conflict with Georgia Lionel Beehner A Contemporary Battlefield Assessment Liam Collins by the Modern War Institute Steve Ferenzi Robert Person Aaron Brantly March 20, 2018 Analyzing the Russian Way of War: Evidence from the 2008 Conflict with Georgia Contents Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................................................ 1 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 9 Chapter I – History of Bad Blood ................................................................................................................ 13 Rose-Colored Glasses .............................................................................................................................. 16 Chapter II – Russian Grand Strategy in Context of the 2008 Russia-Georgia War ................................... 21 Russia’s Ends ........................................................................................................................................... 22 Russia’s Means ........................................................................................................................................ 23 Russia’s Ways ......................................................................................................................................... -

Georgia Page 1 of 21

Country Report on Human Rights Practices in Georgia Page 1 of 21 Georgia Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2006 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 6, 2007 The constitution of the Georgian republic provides for an executive branch that reports to the president, a unicameral Parliament, and an independent judiciary. The country has a population of approximately 4.4 million. In 2003 former president Shevardnadze resigned during what became known as the Rose Revolution. Mikheil Saakashvili won the presidency in 2004 with over 90 percent of the vote in an election, and his National Movement Party won a majority of seats in the Parliament. International observers determined that the 2004 presidential and parliamentary elections represented significant progress over previous elections and brought the country closer to meeting international standards, although several irregularities were noted. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control of the security forces. The government's human rights record improved in some areas during the year, although serious problems remained. While the government took significant steps to address these problems, there were some reports of deaths due to excessive use of force by law enforcement officers, cases of torture and mistreatment of detainees, increased abuse of prisoners, impunity, continued overuse of pretrial detention for less serious offenses, worsened conditions in prisons and pretrial detention facilities, and lack of access for average citizens to defense attorneys. Other areas of concern included reports of government pressure on the judiciary and the media and - despite a substantial reduction due to reforms led by the president - corruption. -

Russia As a Humanitarian Aid Donor

OXFAM DISCUSSION PAPER 15 JULY 2013 RUSSIA AS A HUMANITARIAN AID DONOR ANNA BREZHNEVA AND DARIA UKHOVA This paper addresses the role of Russia as a humanitarian aid donor in the context of the increasing participation in international aid of so-called ‘new’, ‘emerging’ (or ‘re-emerging’), or ‘non-traditional’ donors. In the recent years Russia has made a number of international aid commitments, for example within the G8, marking its re-emergence as an international donor since the disintegration of the Soviet Union. In line with Russia’s increasing international aid commitments, the level of Russian humanitarian aid has also been increasing over recent years. Nonetheless, the country still faces several obstacles in developing its donor capacity. Oxfam Discussion Papers Oxfam Discussion Papers are written to contribute to public debate and to invite feedback on development and humanitarian policy issues. They are ‟work in progress‟ documents, and do not necessarily constitute final publications or reflect Oxfam policy positions. The views and recommendations expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of Oxfam. For more information, or to comment on this paper, email Daria Ukhova [[email protected]] www.oxfam.org CONTENTS Summary ............................................................................ 2 1 Introduction .................................................................... 4 2 Institutional arrangements .............................................. 5 3 How much aid? .............................................................. -

Regulating Trans-Ingur/I Economic Relations Views from Two Banks

RegUlating tRans-ingUR/i economic Relations Views fRom two Banks July 2011 Understanding conflict. Building peace. this initiative is funded by the european union about international alert international alert is a 25-year-old independent peacebuilding organisation. We work with people who are directly affected by violent conflict to improve their prospects of peace. and we seek to influence the policies and ways of working of governments, international organisations like the un and multinational companies, to reduce conflict risk and increase the prospects of peace. We work in africa, several parts of asia, the south Caucasus, the Middle east and Latin america and have recently started work in the uK. our policy work focuses on several key themes that influence prospects for peace and security – the economy, climate change, gender, the role of international institutions, the impact of development aid, and the effect of good and bad governance. We are one of the world’s leading peacebuilding nGos with more than 155 staff based in London and 15 field offices. to learn more about how and where we work, visit www.international-alert.org. this publication has been made possible with the help of the uK Conflict pool and the european union instrument of stability. its contents are the sole responsibility of international alert and can in no way be regarded as reflecting the point of view of the european union or the uK government. © international alert 2011 all rights reserved. no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without full attribution. -

Political Prisoners in Post- Revolutionary Georgia

After the rose, the thorns: political prisoners in post- revolutionary Georgia Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. Article 2: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, spirit of brotherhood. Article 2: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty. Article 3: Everyone has be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty. Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person. Article 4: No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the the right to life, liberty and security of person. -

Chronicle: the Caucasus in the Year 2009

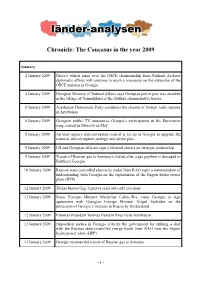

Chronicle: The Caucasus in the year 2009 January 2 January 2009 Greece, which takes over the OSCE chairmanship from Finland, declares diplomatic efforts will continue to reach a consensus on the extension of the OSCE mission in Georgia 4 January 2009 Georgian Ministry of Internal Affairs says Georgian police post was attacked in the village of Ganmukhuri at the Abkhaz administrative border 6 January 2009 Azerbaijan Democratic Party condemns the closure of foreign radio stations in Azerbaijan 6 January 2009 Georgian public TV announces Georgia’s participation in the Eurovision song contest in Moscow in May 8 January 2009 An inter-agency anti-corruption council is set up in Georgia to upgrade the national anti-corruption strategy and action plan 9 January 2009 US and Georgian officials sign a bilateral charter on strategic partnership 9 January 2009 Transit of Russian gas to Armenia is halted after a gas pipeline is damaged in Southern Georgia 10 January 2009 Russian state-controlled electricity trader Inter RAO signs a memorandum of understanding with Georgia on the exploitation of the Enguri hydro power plant (HPP) 12 January 2009 Tbilisi Mayor Gigi Ugulava rules out early elections 12 January 2009 Swiss Foreign Minister Micheline Calmy-Rey visits Georgia to sign agreement with Georgian Foreign Minister Grigol Vashadze on the protection of Georgia’s interests in Russia by Switzerland 12 January 2009 Estonian President Toomas Hendrik Ilves visits Azerbaijan 13 January 2009 Opposition parties in Georgia criticize the government for striking -

An Ambivalent 'Independence'

OswcOMMentary issue 34 | 20.01.2010 | ceNTRe fOR eAsTeRN sTudies An ambivalent ‘independence’ Abkhazia, an unrecognised democracy under Russian protection NTARy Wojciech Górecki Me ces cOM Abkhazia – a state unrecognised by the international community and depen- dent on Russia – has features of a democracy, including political pluralism. This is manifested through regularly held elections, which are a time of ge- tudies nuine competition between candidates, and through a wide range of media, s including the pro-opposition private TV station Abaza. astern e The competing political forces have different visions for the republic’s deve- lopment. President Sergei Bagapsh’s team would like to build up multilateral foreign relations (although the highest priority would be given to relations 1 Despite the lack of with Russia), while the group led by Raul Khajimba, a former vice-president international recognition, entre for it seems unreasonable c and present leader of the opposition, would rather adopt a clear pro-Moscow to use the form ‘self- orientation. It is worth noting that neither of the significant political forces appointed’ or ‘so-called’ president, or to append wants Abkhazia to become part of Russia (while such proposals have been inverted commas to the term (which also con- made in South Ossetia), and a majority of the Abkhazian elite sees Russia’s NTARy cerns other Abkhazian recognition of the country’s independence as a Pyrrhic victory because Me officials and institutions) it has limited their country’s room for manoeuvre. However, all parties are because Bagapsh in fact performs this agreed in ruling out any future dependence on Georgia.